Difference between revisions of "Economic: Kujenga"

(Created page with "''This page is a section of Kujenga.'' The Caucasus countries that possess hydrocarbon resources will continue to depend on the oil and gas industries to drive their eco...") |

|||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <div style="font-size:0.9em; color:#333;margin-bottom:25px;" id="mw-breadcrumbs"> | |

| + | [[Africa|DATE Africa]] > [[Amari]] > '''{{PAGENAME}}''' ←You are here | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="float:right">__TOC__</div> | ||

| − | + | Kujenga, one of East Africa’s largest economies, relies heavily on natural gas and mineral extraction as its main source of revenues. Following a global financial crisis, Kujenga recapitalized its banking sector and implemented regulatory reforms. Since then, agriculture, telecommunications, and the service sector has experienced modest growth. Kujenga’s regional economic competitors are [[Amari]] and [[Ziwa]]. | |

| − | + | Despite efforts to grow a viable middle class by diversifying the economy, most Kujengans—70 percent—still live on less than one dollar per day. A small group of oligarchs retain Kujenga's economic power, publicly paying lip service to government reforms while privately restricting social status, affluence, and acquisition of wealth to a caste of corporate and political power brokers. Within this select group, reciprocal patronage and nepotism remain the order of the day. | |

| − | + | Inadequate electrical power generation capacity tops the list of Kujenga’s economic infrastructure issues. Proposed economic reforms aimed at improving existing capacity consistently bog down in the legislature. Corruption pervades an inefficient property registration system, restrictive trade policies, and a top-heavy regulatory bureaucracy. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Unreliable dispute resolution mechanisms, combined with corporate security concerns, make foreign investors wary of committing limited venture capital to oil, natural gas, and water resource projects. Despite these challenges, Kujenga remains well-grounded in the global economy. No economic sanctions exist that might limit the country’s participation in the international trading community. | ||

== Table of Economic Data == | == Table of Economic Data == | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|'''Measure''' | |'''Measure''' | ||

|'''Data''' | |'''Data''' | ||

| − | |''' | + | |'''Remarks (if applicable)''' |

| − | |''' | + | |- |

| + | |'''Nominal GDP''' | ||

| + | |$36.11 billion | ||

| + | |Agriculture 20.1%, Industry 20.2%, Services 59.7% | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |'''GDP''' | + | |'''Real GDP Growth Rate''' |

| − | | | + | |7.6% |

| − | + | |5 year average 5.2% | |

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |'''Labor | + | |'''Labor Force''' |

| − | | | + | |18.8 million |

| − | | | + | |Agriculture 70.0%, Industry 9.7%, Services 20.3% |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Unemployment''' | |'''Unemployment''' | ||

| − | | | + | |15.8% |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Poverty''' | |'''Poverty''' | ||

| − | | | + | |70.1% |

| − | | | + | |% of population living below the international poverty line |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |'''Investment''' | + | |'''Net Foreign Direct Investment''' |

| − | | | + | |$1.62 billion |

| − | + | |No outbound FDI | |

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Budget''' | |'''Budget''' | ||

| − | |$ | + | |$5.49 billion revenue |

| − | + | $10.85 billion expenditures | |

| − | $ | + | | |

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |'''Public | + | |'''Public Dept.''' |

| − | | | + | |119.8% of GDP |

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Inflation''' | |'''Inflation''' | ||

| − | | | + | |15.1% |

| − | | | + | |5 year average 8.7% |

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

== Participation in the Global Financial System == | == Participation in the Global Financial System == | ||

| − | Over the past | + | Over the past two decades, Kujenga joined with other East African states seeking tighter integration with the global economic system. It established bilateral trading arrangements within East Africa and elsewhere on the continent, and pursued participation in regional and international trading communities to market its products. Kujenga’s eclectic approach to trade, loans, and grants renders it willing to accept help from the International Monetary Fund and all quarters of the globe, including North America, Olvana, Donovia, Western Europe, and the Middle East. For that reason, it defies placement within Eastern or Western spheres of economic influence, and represents a potential “wild card” regarding future participation in regional trading communities and markets. |

=== World Bank/International Development Aid === | === World Bank/International Development Aid === | ||

| − | The World Bank | + | The World Bank maintains an active portfolio for Kujenga. Earlier this year the bank’s board of executive directors authorized a new country partnership strategy that includes support for an ambitious program of development for the next five years. Kujenga has committed to lifting bureaucratic roadblocks that currently hinder its economy from achieving broad-based, inclusive economic growth and a corresponding reduction in poverty. |

| − | + | The country’s overall strategy focuses on economic diversification in order to reduce its reliance on natural resource extraction—which historically has rendered the country vulnerable to volatility inherent in commodities markets. The World Bank’s support strategy for Kujenga is structured around three priorities: | |

| + | * Promoting diversified growth and job creation by reforming the power sector, improving agricultural productivity, and increasing the population’s access to financial support systems | ||

| + | * Improving and expanding the delivery of basic essential services | ||

| + | * Strengthening governance and public sector management through initiatives in gender equity, ethnic conflict amelioration, and an anti-corruption campaign | ||

| + | Kujenga’s major donors are the US, Europe, and Olvana. | ||

| − | === Foreign Direct Investment === | + | === Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) === |

| − | + | Kujenga actively encourages FDI. It is also strategically situated for expanded participation in East African markets, to include transportation infrastructure. The Kujengan government is generally sympathetic to open-market dynamics and promotes public-private partnerships and strategic cooperative arrangements with prospective foreign investors. The US remains the largest foreign investor in Kujenga, with investments concentrated in wheat, vehicles, machinery, kerosene, lubricating oils, jet fuel, civilian aircraft, and plastics. Over the past 12 years, Olvana has invested $2.5 billion in Kujenga's transportation sector and $100 million in the technology sector. Olvanan citizens have also acquired $1 billion worth of the Kujengan real estate. | |

| − | + | Several government-sponsored initiatives are being launched to encourage FDI, particularly in agriculture, mineral extraction and exploration, and export sectors. Tax incentives were implemented to attract pioneering industries the government considers conducive to national economic development and likely to increase employment. Allowances, tax discounts and low-interest loans for business startups are common, with more on the drawing board for hydrocarbon extraction industries. However, investment in the oil and gas sectors is limited to joint ventures or production-sharing agreements. Industries directly linked to national security—such as weapons research and development and the production of munitions—are closely regulated by the government and in some cases operate as state-run enterprises. | |

== Economic Activity == | == Economic Activity == | ||

| − | + | Kujenga is an emerging, middle-income, mixed open market economy with expanding manufacturing, financial, service, communications, and technology sectors. Kujenga produces some goods and services for its own domestic consumption, as well as mining products for all of East Africa. Kujenga recently standardized its record-keeping system to capture rapidly growing contributors to its GDP, especially including telecommunications and banking. Twelve years ago Kujenga reached a milestone agreement with the Paris Club of lending nations, with a view towards eliminating all of its former bilateral external debt. Under this arrangement, the lender nations will forgive most of the debt, in return for Kujenga paying off the remaining balance with a portion of its future energy revenues. | |

| + | |||

| + | Along with seeking relief from its bilateral debt burden, Kujenga attempted to raise the country’s standard of living by achieving a variety of goals, including: macroeconomic stability, deregulation, privatization, relaxation of investment constraints, and record-keeping transparency and accountability. Chronic corruption presents a formidable barrier to achieving many of the reforms. | ||

=== Economic Actors === | === Economic Actors === | ||

| − | + | Mineral deposits and natural gas account for most of Kujenga’s export earnings and the bulk of its revenue. However, the first recession in a quarter-century hit the country last year as a result of falling commodity prices. The situation created a shortage of dollars that has left domestic companies struggling to pay for imported goods. The dollar shortage, in turn, increases the burden on local agriculture to meet the demand for domestic food production. Currently all raw sugar has to be imported, as does flour for milling. | |

| − | + | To alleviate this situation, Africa’s richest man—Homer Ono—is planning to invest $4 billion in sugar production and $1 billion in dairy production over the next three years. His goal is to relieve the dollar shortage in Kujenga. Ono's cement enterprise is the biggest corporation listed on the Kujenga Stock Exchange. Its entry into the agricultural and dairy spheres dovetails with the government’s effort to diversify away from oil. The company’s newly created subsidiary, Ono Rice Limited (ORL), is scheduled to list on the Kujengan Stock Exchange in the near future. | |

| − | + | ORL plans to acquire 900,000 acres of land for sugar cane cultivation, and another 500,000 acres for rice cultivation. The company ordered 5 sugar milling plants from Germany and 10 rice milling plants from the Europe, all to be placed in the southern part of Kujenga. Additionally, the corporation is on the cusp of investing in other agricultural projects, including soybeans, oil palms, palm kernel, and corn. ORL plans to reinforce rice cultivation by providing high-yield seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers to farmers under contract. | |

| − | + | Kujenga’s major challenge in the coming years will be managing its economic system in a way that affords a greater proportion of its population access to affluence and a higher standard of living. The logical place to start is tackling corruption. In Kujenga, the poor do not benefit from the country’s wealth because of corruption and excessive influence that big business and the economic elite have over the formulation of government policy. | |

| − | + | === Trade === | |

| − | + | Prior to the post-independence mineral surge a half-century ago, agriculture was Kujenga’s largest export sector. Afterwards, the country’s economy became largely mineral-intensive and the agricultural sector faded in importance. Agricultural exports are currently at a low point because the recent drop in oil prices caused a dollar shortage, in turn creating pressure on local agribusinesses to increase their output to meet the domestic demand for food products. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Kujenga is currently unhindered by any international restrictions or sanctions that might adversely affect international trade participation. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Commercial Trade === | === Commercial Trade === | ||

| − | + | Besides the dominant gemstone and industrial diamond trade, Kujenga exports mostly seafood, coffee, tea, spices, cocoa and rubber. The country’s major export partners are the United States, Spain, Ziwa, and Amari. Its major import partners are the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, and Olvana. Refined petroleum products, machinery, heavy equipment, consumer goods, and food products are Kujenga’s major imports. | |

| − | + | Kujenga is a potentially lucrative market for adaptable companies willing to navigate a complex and evolving business environment. The country possesses abundant natural resources, cheap labor, and a youthful population (two-thirds under the age of 25). Rising incomes resulting from urbanization and consumer spending, which accounts for two-thirds of Kujenga’s GDP, are helping drive the economy forward. Young Kujengans are as tech-savvy as their American counterparts, and prospective foreign investors can expect substantial growth opportunities in information and communications technology, consumer goods, and the retail industry. Optimistic forecasts show growth in real estate development due to population increases, urban migration, and a rising middle class providing associated growth in the food and agriculture sectors, and infrastructure development. | |

=== Military Exports/Imports === | === Military Exports/Imports === | ||

| − | + | Kujenga exports no significant quantities of hardware, logistical support items, or other services in the military category. Over the past five years, the country’s annual military expenditures were less than 0.5 percent of its GDP. | |

| − | + | Meanwhile, analysts judge the country’s industrial base to be insufficient to meet the surge of maintenance, spare parts, and equipment upgrade needs associated with a major unexpected deployment or sustained expeditionary operation. Similarly, Kujenga’s current industrial base cannot underwrite significant military export trade. As a result, the country will be wholly dependent on external assistance. | |

== Economic Diversity == | == Economic Diversity == | ||

| − | + | Although mineral extraction can be a lucrative source of national income, it also makes the country vulnerable to fluctuations in the international commodities market. Largely for that reason, Kujenga’s main challenge in the economic arena is to diversify. | |

| + | |||

| + | So far, economic diversification efforts and strong growth in the information and communications technology, services, and agricultural sectors have not significantly improved poverty levels, which now stand at over 70 percent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kujenga is far from achieving economic self-sufficiency. Lack of infrastructure—particularly in the transportation arena—is a major challenge to economic development, even as it presents a potential lucrative market attractive to foreign investors. Government reforms aimed at making Kujenga’s economy more entrepreneurial and business-friendly remain very much a work-in-progress, and are hampered by the persistent endemic corruption that pervades the national culture. | ||

=== Energy Sector === | === Energy Sector === | ||

| − | + | Government authorities monitor the energy sector very closely because of recent natural gas finds in southeast Kujenga and along the Indian Ocean coast constitute a potential windfall of revenues and export earnings. The government jealously guards its prerogatives in controlling the exploitation and extraction of natural resources. | |

| − | + | Despite huge potential reserves of natural gas, the energy sector is antiquated, primarily owing to inadequate infrastructure. The main inhibitors of progress include a shortage of port facilities capable of loading and unloading heavy cargoes and poorly maintained roads. The lack of a standardized record-keeping system is also a problem. Up-to-date corporate financial information is rarely available, and when available, is unreliable. | |

=== Oil === | === Oil === | ||

| − | + | Kujenga’s modest crude oil reserves, like its natural gas reserves, are concentrated in the southeast quadrant of the country, near the border with Malawi and along the coast adjacent to the Indian Ocean. Most of Kujenga’s oil extraction occurs in offshore fields near its eastern coast. Conservative assessments place recoverable reserves at just over 1 billion barrels, with more optimistic figures double that. Most of the country’s oil exports are shipped to US and Western European markets, mainly because Kujenga lacks the pipeline and power-plant infrastructure required to support a robust domestic refining capacity. As a result, Kujenga does not produce enough fuel to meet its own domestic energy needs. Refined products must be imported for because Kujenga’s refining infrastructure is inadequate to meet local demand. The country's single refinery is currently only used as a storage terminal as it cannot economically compete with refined imports. | |

| − | + | The government formerly centralized manufactured oil distribution in a vain effort to keep domestic prices at reasonable levels. More recently, as a result of government reforms aimed at spurring foreign investment in the oil industry, market dynamics caused short-term oil price increases, creating an oil theft problem. Because armed gangs establish roadblocks to “tax” large quantities of manufactured oil, many major oil companies sold drilling sites in Kujenga’s interior and relocated to offshore drilling sites. | |

=== Natural Gas === | === Natural Gas === | ||

| − | + | Kujengan recoverable natural gas reserves are estimated between 35 and 80 trillion standard cubic feet (SCF). Initial exploration is underway. Most of the country’s natural gas fields are located offshore. Had government strategies focused more on tapping into these vast gas resources over the past decade—and less on becoming a major player in crude oil production—Kujenga likely could have inoculated itself against the volatility of the international crude oil market. This was not the case, and a hesitancy to invest in this burgeoning gas sector failed to develop the necessary gas-producing infrastructure. | |

| − | + | Apart from infrastructure issues, activities of vandals, pirates, and armed extremists periodically choke off linkages between domestic gas fields and terminals. Several years ago Kujenga and Amari signed a memorandum of understanding intended to connect gas fields in both countries to the Trans-Sahara Gas Pipeline, but this ambitious bilateral project has yet to be completed. | |

| − | + | As with the oil-related issue of refinery shortfalls, the main debate in Kujenga is how to best use the recovered natural gas. Domestically, there is a huge potential for clean-burning power plants that would rapidly increase the Kujengan power grid, stimulating domestic industry. An alternative use is the export of liquefied natural gas. Both would require large investments and both alternatives have powerful advocates among the Kujengan elites. | |

=== Agriculture === | === Agriculture === | ||

| − | + | Despite the fact that the agricultural sector of Kujenga’s economy employs 70 percent of its population, only 20 percent of the country’s GDP is attributed to agricultural production. Compared to former levels, Kujenga’s export of agricultural products decreased considerably last year when the national economy entered a recession. | |

| + | |||

| + | The country suffers from what is commonly called an agricultural paradox. A half-century ago, Kujenga was able to feed its own population. In the aftermath of achieving independence, however, the country sought wealth by becoming increasingly reliant on other economic sectors, such as natural gas production. As a result, three years ago Kujenga reached a point where only 2 percent of the national budget was directed toward agriculture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The main reason why over 70 percent of the population still lives in extreme poverty is that a large proportion of Kujenga’s farmers remain mired in subsistence (as opposed to staple) agriculture. Thus, government reforms oriented toward economic diversification and strong growth did not translate into reduced poverty levels. One part of the problem is the absence of a viable transportation infrastructure necessary for moving farm produce from the rural hinterlands to urban centers where demand is concentrated. Another dimension of the problem is a paucity of storage facilities where farmers could time the release of their produce to coincide with periods where market conditions would allow them to maximize profits. A third aspect is a lack of milling capacity; in example, the areas capable of producing the highest quality of rice crops must sometimes ship it to other regions for milling before it can be sold at market. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Programs aimed at cross-leveling milling capabilities and addressing other farm-related issue, are being implemented. Results vary from region to region, and at different levels of bureaucracy and government. Despite the fact that 70% of the population is engaged in some form of agriculture, Kujenga is still dependent on foreign aid to feed its population. It is noteworthy, for example, that wheat is among the items exported to Kujenga by the US. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Issues surrounding legal titles confirming land ownership, transportation and infrastructure, and persistent security issues make US corporations hesitant to enter Kujenga’s agribusiness sector. The country is signatory to an agreement among East African nations that commits them to direct 10 percent of their respective annual budgets to growing the agricultural sector, but many Kujengan farmers remain doubtful that their government will make good on these commitments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Attitudes among farmers suggests a near consensus that there has been far more government talk than action. In other words, government reforms are only slowly making their way down through Kujenga’s 30 regions to the 143 districts where rural, township, and village councils have input into decisions affecting agricultural initiatives and quality of life issues important to farmers. | ||

| − | + | Security, particularly in remote areas is another significant concern. Farmers in some remote districts complain that their greatest challenge is the nefarious activities of foreign nomadic herdsmen and a variety of militant non-state actors. This is especially problematic in locales where farmers’ dwellings are miles away from sites where they cultivate crops. A lack of consistent government presence makes farmers reluctant to leave their families for any extended period because of security issues. | |

=== Mining === | === Mining === | ||

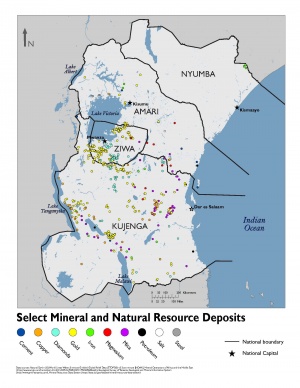

| − | + | [[File:DATE Africa Mining Map.jpg|thumb]] | |

| + | Kujenga’s mining sector is still underdeveloped, contributing only 0.5 percent of the nation’s GDP. However, a mining sector roadmap approved by parliament 18 months ago established the goal of extraction operations contributing 10 percent of the nation’s GDP before the end of the next decade. To demonstrate the government’s commitment mining as a part of wider economic diversification efforts, parliament this year made the country’s mining sector the beneficiary of a $ 3.5 billion capital allocation carved out of the current national budget. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mining industry experts and geologists regard Kujenga as East Africa’s mineral giant, albeit one that has yet to awaken to realize its full potential within the global economy. The country is endowed with vast mineral resources, including gold and diamond deposits formerly overlooked as foreign investors both during and after the colonial. In addition to untapped reserves, new technologies may be brought to bear on closed and abandoned mines to make them profitable again. Although foreign investors are typically attracted by the costs-to-profit ratios offered by precious metals, Kujengan authorities are also mindful of the need to link mining operations to improving national infrastructure. Kujenga’s coal deposits, for example, could potentially generate electrical power generation nodes either collocated with or in close proximity to mining operations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Kujengan parliament’s roadmap for economic diversification envisions the government as an enabler in the nation’s mining sector, as opposed to a major operator. The intent is to create an environment conducive to large and small companies and entrepreneurs entering an industry supported by a variety of incentives, including tax breaks, predictable and regulatory parameters, access to finance, and clearly defined licensing regimes. | ||

=== Manufacturing === | === Manufacturing === | ||

| − | + | The manufacturing sector of Kujenga’s economy remains more or less in a chronically developmental state due to a combination of power generation crises and an unhealthy competition between locally manufactured goods and imported goods. Industry/manufacturing ranks lowest among the three sectors that together comprise the totality of Kujenga’s GDP, accounting for 20 percent of the aggregate. Agriculture and services respectively account for 25 percent and 65 percent. Manufacturing industries include natural gas, oil, coal, tin, columbite, rubber products, wood, hides and skins, textiles, cement and other construction materials, food products, footwear, fertilizer, and ceramics. Kujenga’s industrial production ranks third in East Africa, behind first place Amari and second place Ziwa, but ahead of Nyumba, whose industrial production base is negligible. Kujenga ranks 195th in standing throughout the world at large. | |

| + | A lack of infrastructure, specifically sufficient electrical power to sustain industrial operations tends to discourage prospective foreign investors. Another drawback is the absence of quality control measures that would ban substandard manufactured goods from the marketplace. In the local economy, the low income of many Kujengans entices purchasers to prefer cheaply-made products simply because they are less expensive than legitimate products that meet quality control standards. Despite efforts at reform, the court system has yet to demonstrate a capacity to prosecute offenders who intentionally flood local markets with cheaply made products. | ||

==== Steel ==== | ==== Steel ==== | ||

| − | + | Kujenga’s steel production barely registers compared with other regional countries or from a worldwide perspective. The steel sector in Kujenga suffers from many of the same shortfalls as other sectors in the country’s national economy. Existing infrastructure is grossly inadequate in terms of both capacity and quality, nor is it configured to support large-scale expansion in the foreseeable future. One major problem is raw material. Steel plants require a steady supply or iron ore, and so far, very little has been done to link domestic extraction/mining operations to steel manufacturing. As a result, steel used by Kujenga’s few manufacturing facilities must be imported. | |

| + | |||

| + | The anemic and unpredictable electricity supply is another major reason behind the lack of progress in the steel sector. Plant managers continuously enjoin government officials and utility suppliers to improve the electrical grid, both nationally and locally. Electrical outages and random voltage fluctuations are the norm, causing damage to machinery and equipment. Consequently, most steel firms pursue a self-help strategy that entails procuring gasoline powered backup generators to maintain continuity of operations. This in turn drives up operating costs and hinders the ability of local companies to compete with foreign steel producers. Domestic steel consumption demand is steady and expected to increase over time, but far more public/private sector collaboration will be necessary in order to achieve any significant level of indigenous production capacity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Automotive ==== | ||

| + | Kujenga’s once robust civilian automotive industry is now struggling for traction in a recession economy. This year the government banned the importation of motor vehicles through the nation’s land borders, mainly because authorities are trying to curb large-scale smuggling operations that prevent authorities from collecting tax revenues. Smuggling operations also hamper the competitiveness of local car producers. Importers try to bypass Kujenga’s official ports of entry, preferring to send their cargoes to seaports of neighboring countries—like Amari—and then avoid paying duties by smuggling the vehicles through porous land borders. Smugglers can avoid paying any taxes whatsoever, or simply pay minor bribes to guards ostensibly safeguarding official entry points. Many individual consumers personally travel from Kujenga to Amari, Ziwa, or Nyumba to buy cars from shady dealers located just across international boundaries, then drive their purchases home without paying any taxes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Kujengan Customs Service estimates that over half the vehicles imported in Nyumba and Amari are in transit to Kujengan markets. This particularly common pre-owned vehicles. Last year’s economic downturn predictably all but killed demand for new cars, but spurred an influx of used cars into the Kujengan market. Large-scale smuggling of used cars into Kujenga is probably the biggest deterrent to generating a sustainable domestic national market in new vehicles and spare parts. | ||

| − | + | Because falling disposable incomes, unemployment, and high inflation resulting from the continuing recession has canalized prospective customers into the used market, the automotive sub sector of Kujenga’s economy shrank by one-third between July and September last year. Despite an optimistic government reform program that envisions a revitalized automotive sector within a ten-year timespan, near-term prospects for Kujenga’s automotive industry remain doubtful. | |

| − | |||

==== Petrochemicals ==== | ==== Petrochemicals ==== | ||

| − | + | Kujenga possesses only a small fraction of the petrochemical manufacturing capacity it might otherwise be capable of generating if its manufacturing companies would depend more on locally produced materials. Almost all of Kujenga’s manufacturers import about 80 percent of their raw materials. Virtually all of the foam, plastic, paint, and textile companies in the country depend on derivatives, most of which are imported, largely because earlier political regimes failed to diversify the country’s economy in their headlong rush to expand hydrocarbon extraction capability to the exclusion of manufacturing sectors. | |

| + | |||

| + | There are currently three petrochemical plants present in Kujenga, only one of which—at Dar es Salaam—is operating. Four years ago this functioning plant had a capacity to produce 300,000 metric tons of elfins (synthetic fibers), 250,000 metric tons of polyethylene, and 100,000 metric tons of polypropylene. A former president of the fledgling Polymer Institute of Kujenga recently advocated putting additional pressure on the government to curtail imports of petrochemicals in favor nurturing the capability to produce polymers in the home country. This is particularly true with regard to manufacturing the plastics needed to bottle large amounts of table water that could then service markets in drought-stricken regions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The government is attempting to attract foreign direct investment into Kujenga’s petrochemical sector. However, a shortage of skilled labor, political and social unrest, and sabotage of infrastructure could delay or prevent many of these projects from coming to fruition. The main drawing card for foreign direct investment is the fertilizer sector, which has access to domestic gas resources and is judged to have high potential for penetrating markets in Amari, Ziwa, and Nyumba, as well as throughout the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. | ||

==== Defense Industries/Dual Use ==== | ==== Defense Industries/Dual Use ==== | ||

| − | + | For all practical purposes, Kujenga lacks any semblance of a military industrial base. For each of the past five years, military expenditures have not exceeded 0.5 percent of Kujenga’s national GDP. Domestically, the armed forces are mainly preoccupied with sustaining government authority, and suppressing criminal elements, extremist groups, and marginalized tribes all of whom threaten to undermine the rule of law under the country’s constitutional charter. | |

| + | |||

| + | Although piracy in the Indian Ocean poses a potential maritime threat to Kujenga’s sovereignty and economic well being, the likelihood of conventional cross-border incursions by armed forces of neighboring states is judged to be unlikely. At present no real capability exists to reverse-engineer and/or replicate technologically advanced products obtained from foreign sources. However, such a capability could come within reach as indigenous information and communications infrastructure continues to progress and become more sophisticated over time. Kujenga possesses no industrial base capable of transitioning from peacetime production to a wartime footing. | ||

==== Services ==== | ==== Services ==== | ||

| − | Domestic services | + | From the standpoint of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), services is the most important sector of Kujenga’s national economy—accounting for 60 percent of GDP last year, in comparison to 20 percent of GDP for agriculture, and 10 percent each for hydrocarbons and manufacturing. Much of the percentage spike in the services sector derives from a government program that rebased the GDP 3 years ago. Within the services sector, the major venues (or subsectors) that saw growth were telecommunications, banking, the film industry (called “Nollywood”), and the informal economy, which previously was invisible in official statistics. Service industries that contributed substantial shares to Kujenga’s GDP 3 years ago were the wholesale and retail trade, real estate, and telecommunications services. |

| + | |||

| + | The government’s focus on reform over the past 5 years—formally set forth in the Kujenga Forward Leap Agenda—sought to address chronic infrastructure shortfalls that historically inhibited private sector growth. Long-term funding programmed to underwrite this economic transformation effort will come from a combination of incremental federal budget disbursements to targeted subsectors, and expanded public-private partnerships (PPPs). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although momentum within this agenda varies from sector to sector, and endemic corruption periodically undermines the benevolent policies of democratically elected leaders, anecdotal indicators suggest that, on balance, progress is being made. Several major PPPs are currently being co-financed by Olvana’s Export-Import Bank. Kujenga, meanwhile, initiated one of the world’s most extensive privatization efforts in the power sector—which requires an infusion of about $50 billion over the next couple of years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These infrastructure reform efforts are paying off by enticing a special breed of venture capitalists to the East African marketplace. Through that channel, Kujenga became one of the region’s leading beneficiaries of private inward FDI some eight years ago, with the services sector accounting for about half of all new projects funded since the economic downturn 9 years ago. These positive indicators, however, need to become less sporadic and more commonplace. Despite anecdotal progress in some venues, Kujenga’s most serious economic problem persists: strong growth and cross-leveled resources in a few key sectors have not translated into a significant decline in poverty levels for over 60 percent of the population, who remain beyond the reach of financial services considered key to achieving food security and increased affluence. | ||

== Banking and Finance == | == Banking and Finance == | ||

=== Public Finance === | === Public Finance === | ||

| − | + | Over the past several decades, legacy government programs and policies intended to achieve a robust national economy with diverse sectors have fallen woefully short of expectations. An almost exclusive reliance on profits from hydrocarbons resulted in the government failing to establish and maintain a viable revenue base. For years Kujenga ran a $300 billion economy while operating with a $20 billion income stream. Most of the difference between these two sums was made up through deficit spending and external loans. A former chief executive officer of the National Bank of Kujenga, noting how the national budget persisted in authorizing bloated recurrent expenditures, characterized the country’s public finance as a broken system. Because almost 100 percent of the national capital is borrowed, Kujenga’s debt burden is untenable. | |

| − | + | These macroeconomic considerations are not unrelated to chronic and rampant corruption in the public financial system. Kujenga’s constitution provides for a fund to underwrite selected government capital development projects. Monies obtained from external loans typically flow through this Development Fund, which suffers from a lack of transparency. Numerous elected and appointed officials charged with financial oversight responsibilities have redirected public monies into their personal accounts. It is common knowledge throughout Kujenga that millions of dollars have disappeared from Development Fund projects, with little or no explanations provided as to why the shortfalls happened, or measures being considered to prevent recurrences. | |

| − | + | Since the glut in the world oil market triggered an economic downturn two years ago, inflation has been on the rise in Kujenga. The shrinkage of the hydrocarbon market caused a domestic currency shortage, which in turn drove up food prices. The current inflation rate stands at 16 percent. | |

==== Taxation ==== | ==== Taxation ==== | ||

| − | + | Taxes and other revenues accounted for only 2 percent of Kujenga’s GDP last year. Tax avoidance and evasion is practically a national tradition in Kujenga. Analysts estimate that the country loses about $1 trillion annually because of the failure of individuals and corporations to file tax returns as required by law. Accordingly, the government recently initiated a plan to broaden the tax base and improve revenue collection mechanisms. It also ratified a multilateral convention to prevent multinational corporations from shifting profits from one country to another as a means of avoiding responsibilities under national tax laws. | |

| + | |||

| + | Kujenga has a personal tax rate of 24 percent, a corporate tax rate of 30 percent, and a sales tax rate of 5 percent. Much of the national tax shortfall problem stems from the absence of an administrative collection infrastructure capable of ensuring that all prospective taxpayers are properly registered. The Kujengan Internal Revenue Service recently mounted a public information campaign crafted to inform all citizens and corporations in Kujenga of their responsibilities under the tax laws. The norm is for all returns to be filed within 90 days after the first of the year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Kujengan government habitually operates at a deficit because it must carry a heavy debt burden. The government borrows money because available funds raised through taxes are not sufficient to meet the budgeted spending. Funds are therefore sought from international donors—such as the US, Western European nations, Donovia, and Olvana—who are willing to lend their excess capital to Kujenga. Initiatives to increase revenues from citizens and corporations alike should improve the national economy over time by increasing Kujenga’s savings and alleviating its external debt burden. | ||

==== Currency Reserves ==== | ==== Currency Reserves ==== | ||

| − | + | Kujenga’s currency reserves have grown over the past 12 months, building fairly consistently from just over $25 billion at the beginning of the period to just under $35 billion within the last quarter. This level was the highest achieved in 3 years. The last time Kujenga reflected $35 billion in currency reserves was 3 years ago when it dropped to that level from a previous high of $37 billion, in reaction to a sharp drop in LNG prices. The recent increases were occasioned by profits garnered from LNG sales following a short-term recovery in the international hydrocarbon market. How long this recovery can be sustained remains to be determined. | |

| + | |||

| + | The official currency of Kujenga is the Arina (KRNA). At the current exchange rate, KRNA 1 billion is the equivalent of $3 million. | ||

==== Private Banking ==== | ==== Private Banking ==== | ||

| − | + | The Kujengan banking system consists of 20 commercial banks, 5 development finance banks, 60 finance companies, and 850 micro-finance banks, all operating under a national system headed by the National Bank of Kujenga (KNB). The KNB issues licenses, and establishes ground-rules and standardized operating procedures applicable throughout the entirety of the national banking community. The KNB’s primary responsibility is to formulate policies and monitor the overall banking system to ensure that operators comply with monetary, credit, and foreign exchange guidelines sanctioned by the Kujengan government and codified in laws passed by parliament. | |

| + | |||

| + | Kujenga’s most important are micro-finance banks. They embody the most recent iteration of government efforts to reboot the national economy in the wake of a contraction in the hydrocarbon market that occurred 3 years ago. Shortly following that downturn, the ruling party, with the bipartisan blessing of opposition parties in parliament, produced a highly popular Economic Revitalization Plan (ERP). The tendrils of this plan reach out to affect all facets of Kujenga’s economy, especially including the banking system. Thus the government neither owns nor operates the banks in Kujenga, but the banks in Kujenga operate under the close scrutiny of, and with the advice and consent of, the government. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A basic feature of the ERP is its advocacy and promotion of businesses that fall within the category of small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). Start-up businesses typically need loans before they can begin operating, and to obtain these loans they turn to commercial banks. An innovative concept reflective of the most recent enacted reforms is the recognition that SMEs are anything but a monolithic grouping. They contain a plethora of extremely small business establishments that constitute a separate category in their own right: micro small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Earlier banking reforms largely overlooked MSMEs, even though they constitute a sizeable portion of the informal economy. Of the 35 million businesses comprising the generic SME sector, about 99 percent (34, 650,000) are microenterprises. The new reforms are based on the premise that, in order to be successful, the banking system must understand how MSMEs contribute to the informal economy, and provide them with essentially the same services that banks traditionally offer better established businesses in the formal economy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another reform implemented following a spate of inspections and examinations by the KNB requires all banks operating in Kujenga to correlate their operational accounting years with calendar years. This was done in order to increase transparency and facilitate easier financial comparisons among banks throughout the national system. A recently published government circular mandates a standardized format for making annual disclosures of institutional financial information. In both the private and public sectors, Kujengan officials welcome foreign ownership of banks as a means of acquiring sound accounting techniques, management expertise, and administrative skills that are often locally unavailable. In order for all these reforms to succeed, the pervasive corruption and culturally conditioned disregard of the rule of law that plagues the Kujengan economy will need to be drastically reduced if not altogether eliminated. | ||

==== Banking System ==== | ==== Banking System ==== | ||

| − | The country’s | + | The National Bank of Kujenga is the cornerstone and mainstay of Kujenga’s national banking system. It establishes Kujenga’s prevalent interest rate and controls the money supply. The KNB is a public institution specifically authorized by a provision in the country’s constitution. The government uses the KNB as a channel for disseminating, implementing, and enforcing banking standards and monetary policy throughout Kujenga. Recent adjustments to these policies include establishing professional standards for record-keeping, adopting the calendar year as a common country-wide timeframe for preparing and submitting annual financial reports, and mandating a national set of ground-rules supportive of private enterprise and an open market economy. |

| + | |||

| + | The announced vision of the KNB is to set the example of a model central bank by delivering price and financial system stability, and cultivating the sustained economic development of the nation. Its mission is to be proactive in providing a stable framework for this development through the effective, efficient, and transparent implementation of monetary, interest rate, and exchange rate policy, while maintaining overall stewardship of the country’s financial sector. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The KBN has 32 branches spread throughout Kujenga. An act passed by parliament 10 years ago authorized establishing a monetary policy committee that has responsibility for formulating a national monetary and credit policy. The KBN’s assets total ARN 24,000,000,000. Its total equity and liabilities also equal that amount. The Kujengan National Bank has about 10 million bank customers spread throughout the nation, the neighboring countries of Amari, Ziwa and Nyumba, and a worldwide diaspora. In part because this bank and its subordinate branches service government agencies and institutions, it is Kujenga’s biggest bank in terms of assets. The KNB provides banking services to government ministries, departments and agencies, and semi-autonomous government institutions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As is generally the case across Africa and throughout the globe, financial inclusion and visibility of enterprises comprising the informal economy have garnered increased attention among the KNB’s financial managers. The importance of this subject derives from the informal economy’s potential as a catalyst for economic development, particularly with regard to poverty reduction, employment generation, wealth creation, and improving the national quality of life by raising living standards. | ||

| − | + | The need to assimilate previously marginalized elements of the population into the formal financial sector recently led the National Bank of Kujenga to grant charters to regional interest-free banks. In this way, Islamic banking—based on principles of profit and loss sharing—has taken root in Kujenga. Under the Islamic banking arrangement, borrowers become partners of the bank, as opposed to being charged interest on loans. Both the lending institution and the borrower share the burden of liability. According to Islamic tenets, interest income is considered a form of usury. For that reason, Islamic banks forbear charging interest for the money they lend. Instead, the lending institution receives an equity share of what it finances, an arrangement that makes the lender a participant in sharing the risk. | |

| − | + | A demographic breakout of Islamic bank customers revealed that 80 percent lived in rural areas, 75 percent were younger than 45 years of age, 55 percent were women, and 35 percent had no formal education. The advent of Islamic banking succeeded in assimilating Muslims into Kujenga’s formal economy. In the past, voluntary exclusion from financial products and services was a conscious choice made by a majority of the country’s Muslim population. Now, thanks to recently granted charters, Islamic banking has the potential to drastically reduce voluntary exclusion from the formal economy due to religious or cultural taboos. In addition, the presence of these banks acts as a brake on the tendency of conventional banking institutions to charge prohibitive interest rates for loans and embed hidden fees in customer accounts. | |

==== Stock/Capital ==== | ==== Stock/Capital ==== | ||

| − | + | Kujenga’s national stock exchange, originally organized as the Dar Es Salaam Stock Exchange, was established 53 years ago, shortly after the country gained its independence. It lists 165 companies as members, and contains 5 specialized indices that cover a spectrum of national economic sectors. These include the Consumer Goods Index, the Kujenga Stock Exchange (KSE) Banking Index, the KSE Insurance Index, the KSE Industrial Index, and the KSE Hydrocarbon Index. The consumer goods sector is somewhat underrepresented, because an unknown proportion of the country’s subsistence farmers, wholly dependent on crop yields for physical as well as economic survival, historically have been invisible on the exchange. The government recently launched an initiative to assimilate this marginalized segment of the population into the country’s formal economy. | |

| + | |||

| + | For the past 18 years the Kujengan Stock Exchange has operated with an automated Trading System (ATS) executed trades through a network of computers, all linked to a central server. The ATS has the capacity to support remote trading, as well as government-mandated surveillance functions. As a result, members of the exchange typically trade online from offices in Dar Es Salaam, as well as from thirteen branch offices geographically dispersed throughout the country. Additional branches are planned to enhance and augment current real-time trading online. | ||

| − | + | Recent reforms adopted by Kujenga’s government encourages market participation by foreign investors. To achieve that goal, parliament abolished legislation that discouraged the flow of foreign capital into the country. Foreign brokers may now register as dealers on the Kujengan Stock Exchange, and investors of any nationality are free to execute trades. Kujenga stock market capitalization reached an all-time high 10 years ago, just prior to the global economic downturn. At that time it represented 35 percent of the country’s GDP. After entering the current recession, it dropped to a level close to 10 percent, remaining in the 10 to 15 percent range ever since. The most recent data on publicly traded shares places the market value at $50 billion as of the end of last year. | |

==== Informal Finance ==== | ==== Informal Finance ==== | ||

| − | + | As in many African countries, Kujenga has a large informal sector, due primarily to an oversized labor pool that lacks the specialized skills demanded by a rapidly modernizing economy. Following the global financial crisis that struck 10 years ago, Kujenga’s economic growth was mainly driven by advances in agribusiness, telecommunications, and financial services. These advances are symptomatic of recent policy changes implemented by the government intended to wean the country away from an almost exclusive dependence on hydrocarbon revenues. Despite these reforms, efforts to achieve strong growth through economic diversification failed to translate into a significant decline in poverty levels. | |

| + | |||

| + | Longstanding cultural/religious biases and taboos—particularly among Muslims who equate conventional banking practices with usury—prejudice a significant portion of the population against participating in the formal economy. Shut out of preferred jobs through a lack of education, failure to learn specialized skills, an historical overdependence on foreign expertise, or personal biases, many laborers are left with little choice but to turn to subsistence farming or menial domestic work as their only means of staving off starvation. These venues—subsistence farming and menial domestic work—are conducive to cash or barter wage payment arrangements that make it easy for payees to remain invisible to government tax law enforcers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Food insecurity resulting from poverty often drives a range of clandestine “moonlighting” activities that include slash-and burn deforestation, poaching, and the sale of commodities on the black market. The same stressors that drive these moonlighting activities contribute to conditions conducive to informal remuneration arrangements, including bartering for goods and services and receiving payment-in-kind in return for labor. Arrangements associated with the informal economy, despite providing a means of payment in exchange for labor, deprive the government of much-needed revenues. | ||

| − | + | Kujenga now has a small but growing number of financial institutions tailored to legally extend Islamic banking practices to customers who indicate a willingness to assimilate into the formal economy. Despite this innovation, some segments of the population persist in their attachment to the informal sector. The informal sector includes a significant number of expatriates who channel private remittances to relatives or lenders via the hawala system—an informal, trust-based network of individuals organized to facilitate fund transfers—thus avoiding government-imposed taxes, and typically tapping into a better exchange rate on foreign currencies than what the government can offer. The hawala system is illegal, and users carry a degree of risk since the state imposes prison sentences and hefty fines on transgressors. | |

== Employment Status == | == Employment Status == | ||

| − | + | === Labor Market === | |

| + | Seventy percent of Kujenga’s 18.8-million-strong labor force works in the agricultural sector, even though that sector accounts for only about 20 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. In contrast, workers in the services sector amount to only about 20 percent of the labor force while their efforts account for 60 percent of Kujenga’s GDP. Essentially, this means that while over time the economy is creating more jobs than in the past, those jobs that are most lucrative from the standpoint of higher pay, affluence, and opportunity for advancement are cordoned within the technology, agribusiness, and financial services sectors. Lack of three qualifications—education, specialization, and management experience—canalize the majority of workers into low-pay or subsistence agricultural and informal services sectors, where opportunities for upward mobility range from meager to nonexistent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While recent government reforms seek to steer the country away from a total dependence on hydrocarbon revenues and toward a more diversified economy, these changes have been slow to take effect, hampered by widespread endemic corruption and legislative bickering. Thus, they have not translated into any significant decrease in Kujenga’s chronically high poverty levels. An analysis of Kujenga’s population demographics reveals a growing youth bulge in the country’s labor force. Kujenga’s labor force in the 15-24 age range has grown steadily over the past ten years from 4 million to almost 6 million workers. This trend is expected to continue throughout the coming decade. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gender roles in Kujenga are changing, eroding old biases that consigned women to the domestic sphere and kept them out of the workplace. For the past ten years, females comprised about 50 percent of Kujenga’s national workforce, up from 35 percent the decade before. Although entrenched traditional biases still pose daunting challenges to prospective female corporate leaders and entrepreneurs, with the help of government reforms, women are making gains in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math. | ||

| − | === | + | === Employment and Unemployment === |

| − | + | Kujenga’s unemployment rate increased steadily over the past 12 consecutive quarters—a 3-year period that began when the country entered its first recession in two decades. The country’s unemployment rate now stands at 16 percent and is unlikely to improve significantly over the coming year. The government threatened to revoke the licenses of businesses who gratuitously dismiss workers, but such heavy-handed measures had little if any impact on a job market where demand far outstrips the modest number of available positions. When a government tax agency with geographically dispersed regional offices announced openings for 5,000 positions, it received over 600,000 applications in response. Similarly, during the same timeframe an agency within Kujenga’s national security force structure that listed openings for 10,000 positions garnered over a million applications. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Labor force turbulence is a perennial problem in Kujenga. People move back and forth between the formal and informal economies, and it is not uncommon for employees to seek a new workplace on a month-to-month basis throughout the year. Kujenga’s youth are most affected by this turbulence. Fraudulent Ponzi schemes abound, as millions of people display a willingness to undertake dubious ventures hoping to make a quick buck in the absence of gainful employment. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In addition to unemployment—defined as either having no livelihood at all or performing some labor for less than 20 hours a week—underemployment is also a major problem. Underemployment is defined as either working more than 20 hours a week but less than 40 hours per week, or alternatively, working full time in some vocation that underutilizes a person’s time, skill, and educational qualifications. Individuals falling within this category include subsistence farmers who typically work seasonally, during planting and harvesting cycles. Employment and underemployment rates in Kujenga mirror the urban and rural divide. Underemployment predominates in rural areas, where most residents engage in subsistence farming; unemployment is higher in urban areas, reflecting the fierce competition for the few coveted white collar positions available in cities. | |

| − | |||

=== Illegal Economic Activity === | === Illegal Economic Activity === | ||

| − | + | Kujenga endures a broad spectrum of [[DATE Africa - Criminal Activity|illegal economic activity]], some of which is grounded in the chronic poverty and famine that has gripped the rural countryside for decades. The illegal economy includes an ethnic factor, as tribes with longstanding traditions of mutual enmity compete for scarce natural resources, including water and grazing land for livestock. Cattle rustling, smuggling, and banditry are common, typically accompanied by ethnic clashes. Accelerated urbanization in recent years caused ethnic animosity to migrate from the rural countryside into the cities, especially during periods of extreme economic hardship and/or intense political agitation. | |

| − | The | + | |

| + | Kujenga is a transit point for heroin and cocaine intended for markets in East Asia, Donovia, Eastern and Western Europe, and North America. It is also the home base and safe haven for the [[Donya Syndicate]]: the largest and most powerful cocaine trafficking operation in East Africa. Boasting a worldwide reach, the syndicate’s primary operating base is Dar Es Salaam, although it also controls several processing and distribution nodes scattered throughout Kujenga. The government has scored only a handful of enforcement successes against the [[Donya Syndicate]], due mainly to the gang’s demonstrated ability to infiltrate legitimate businesses in every sector of the economy. Kujengan narco-traffickers throughout the world blend-in with Kujengan expatriates to conceal their operations from law enforcement agencies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A nexus has developed between the Donya syndicate, competing criminal organizations, and an amalgam of political and paramilitary groups that support a variety of extremist agendas. These groups share at least one proclivity: an eagerness to use illicit proceeds to finance their respective operations. Non-state actors currently operating inside Kujenga include the [[Kujengan Bush Militias|Waaminifu Boys]]—locally known as “The Fu”—a prominent bush militia based in the southern Udzungwa Mountains in the central part of the country. This group, while ostensibly espousing Christian values, is allegedly waging a multi-pronged ethnic cleansing campaign that seeks to annihilate Muslims and select rival tribes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Fu is involved in a broad range of illegal economic activities that encompass piracy, smuggling, money laundering, forced labor, and human trafficking. It is most notorious, however, for political kidnappings for ransom, poaching, and illegal mining and refining operations. The latter two activities are incidentally in direct defiance of recent government initiatives to formally register all wildcat (i.e. extralegal) mining and refining operations throughout the country for the dual purpose of attracting foreign investors and tapping into a potential lucrative source of tax revenues. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Kujengan Bush Militias|Antivurugu Militia]] formed to oppose the Fu but indulges in many of the same tactics and illegal economic activities. As the Islamic counterpart to the Fu, it operates in the northern Udzunga Mountains of central Kujenga. This group, also in league with the [[Donya Syndicate]], demonstrates the brutality typically associated with East African insurgencies. It too has undermined Kujengan authorities—and their status as the legitimate guarantors of national sovereignty—by defying efforts to crack down on illegal mining and refining operations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Corruption poses a serious threat to Kujengan national sovereignty. Accordingly, it undermines government initiatives to implement popularly mandated political, economic, and social reforms. The current government, elected on an anti-corruption platform, has so far achieved only limited success. Earlier this year, when officials arraigned a local hero on charges of abusing his office and running a multi-million dollar scam operation, over a hundred security personnel were deployed to prevent a breakdown of law and order. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:DATE]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Africa]] | |

| − | [[Category:DATE | + | [[Category:Kujenga]] |

| − | [[Category: | ||

| − | [[Category: | ||

[[Category:Economic]] | [[Category:Economic]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:59, 2 July 2020

Kujenga, one of East Africa’s largest economies, relies heavily on natural gas and mineral extraction as its main source of revenues. Following a global financial crisis, Kujenga recapitalized its banking sector and implemented regulatory reforms. Since then, agriculture, telecommunications, and the service sector has experienced modest growth. Kujenga’s regional economic competitors are Amari and Ziwa.

Despite efforts to grow a viable middle class by diversifying the economy, most Kujengans—70 percent—still live on less than one dollar per day. A small group of oligarchs retain Kujenga's economic power, publicly paying lip service to government reforms while privately restricting social status, affluence, and acquisition of wealth to a caste of corporate and political power brokers. Within this select group, reciprocal patronage and nepotism remain the order of the day.

Inadequate electrical power generation capacity tops the list of Kujenga’s economic infrastructure issues. Proposed economic reforms aimed at improving existing capacity consistently bog down in the legislature. Corruption pervades an inefficient property registration system, restrictive trade policies, and a top-heavy regulatory bureaucracy.

Unreliable dispute resolution mechanisms, combined with corporate security concerns, make foreign investors wary of committing limited venture capital to oil, natural gas, and water resource projects. Despite these challenges, Kujenga remains well-grounded in the global economy. No economic sanctions exist that might limit the country’s participation in the international trading community.

Table of Economic Data

| Measure | Data | Remarks (if applicable) |

| Nominal GDP | $36.11 billion | Agriculture 20.1%, Industry 20.2%, Services 59.7% |

| Real GDP Growth Rate | 7.6% | 5 year average 5.2% |

| Labor Force | 18.8 million | Agriculture 70.0%, Industry 9.7%, Services 20.3% |

| Unemployment | 15.8% | |

| Poverty | 70.1% | % of population living below the international poverty line |

| Net Foreign Direct Investment | $1.62 billion | No outbound FDI |

| Budget | $5.49 billion revenue

$10.85 billion expenditures |

|

| Public Dept. | 119.8% of GDP | |

| Inflation | 15.1% | 5 year average 8.7% |

Participation in the Global Financial System

Over the past two decades, Kujenga joined with other East African states seeking tighter integration with the global economic system. It established bilateral trading arrangements within East Africa and elsewhere on the continent, and pursued participation in regional and international trading communities to market its products. Kujenga’s eclectic approach to trade, loans, and grants renders it willing to accept help from the International Monetary Fund and all quarters of the globe, including North America, Olvana, Donovia, Western Europe, and the Middle East. For that reason, it defies placement within Eastern or Western spheres of economic influence, and represents a potential “wild card” regarding future participation in regional trading communities and markets.

World Bank/International Development Aid

The World Bank maintains an active portfolio for Kujenga. Earlier this year the bank’s board of executive directors authorized a new country partnership strategy that includes support for an ambitious program of development for the next five years. Kujenga has committed to lifting bureaucratic roadblocks that currently hinder its economy from achieving broad-based, inclusive economic growth and a corresponding reduction in poverty.

The country’s overall strategy focuses on economic diversification in order to reduce its reliance on natural resource extraction—which historically has rendered the country vulnerable to volatility inherent in commodities markets. The World Bank’s support strategy for Kujenga is structured around three priorities:

- Promoting diversified growth and job creation by reforming the power sector, improving agricultural productivity, and increasing the population’s access to financial support systems

- Improving and expanding the delivery of basic essential services

- Strengthening governance and public sector management through initiatives in gender equity, ethnic conflict amelioration, and an anti-corruption campaign

Kujenga’s major donors are the US, Europe, and Olvana.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Kujenga actively encourages FDI. It is also strategically situated for expanded participation in East African markets, to include transportation infrastructure. The Kujengan government is generally sympathetic to open-market dynamics and promotes public-private partnerships and strategic cooperative arrangements with prospective foreign investors. The US remains the largest foreign investor in Kujenga, with investments concentrated in wheat, vehicles, machinery, kerosene, lubricating oils, jet fuel, civilian aircraft, and plastics. Over the past 12 years, Olvana has invested $2.5 billion in Kujenga's transportation sector and $100 million in the technology sector. Olvanan citizens have also acquired $1 billion worth of the Kujengan real estate.

Several government-sponsored initiatives are being launched to encourage FDI, particularly in agriculture, mineral extraction and exploration, and export sectors. Tax incentives were implemented to attract pioneering industries the government considers conducive to national economic development and likely to increase employment. Allowances, tax discounts and low-interest loans for business startups are common, with more on the drawing board for hydrocarbon extraction industries. However, investment in the oil and gas sectors is limited to joint ventures or production-sharing agreements. Industries directly linked to national security—such as weapons research and development and the production of munitions—are closely regulated by the government and in some cases operate as state-run enterprises.

Economic Activity

Kujenga is an emerging, middle-income, mixed open market economy with expanding manufacturing, financial, service, communications, and technology sectors. Kujenga produces some goods and services for its own domestic consumption, as well as mining products for all of East Africa. Kujenga recently standardized its record-keeping system to capture rapidly growing contributors to its GDP, especially including telecommunications and banking. Twelve years ago Kujenga reached a milestone agreement with the Paris Club of lending nations, with a view towards eliminating all of its former bilateral external debt. Under this arrangement, the lender nations will forgive most of the debt, in return for Kujenga paying off the remaining balance with a portion of its future energy revenues.

Along with seeking relief from its bilateral debt burden, Kujenga attempted to raise the country’s standard of living by achieving a variety of goals, including: macroeconomic stability, deregulation, privatization, relaxation of investment constraints, and record-keeping transparency and accountability. Chronic corruption presents a formidable barrier to achieving many of the reforms.

Economic Actors

Mineral deposits and natural gas account for most of Kujenga’s export earnings and the bulk of its revenue. However, the first recession in a quarter-century hit the country last year as a result of falling commodity prices. The situation created a shortage of dollars that has left domestic companies struggling to pay for imported goods. The dollar shortage, in turn, increases the burden on local agriculture to meet the demand for domestic food production. Currently all raw sugar has to be imported, as does flour for milling.

To alleviate this situation, Africa’s richest man—Homer Ono—is planning to invest $4 billion in sugar production and $1 billion in dairy production over the next three years. His goal is to relieve the dollar shortage in Kujenga. Ono's cement enterprise is the biggest corporation listed on the Kujenga Stock Exchange. Its entry into the agricultural and dairy spheres dovetails with the government’s effort to diversify away from oil. The company’s newly created subsidiary, Ono Rice Limited (ORL), is scheduled to list on the Kujengan Stock Exchange in the near future.

ORL plans to acquire 900,000 acres of land for sugar cane cultivation, and another 500,000 acres for rice cultivation. The company ordered 5 sugar milling plants from Germany and 10 rice milling plants from the Europe, all to be placed in the southern part of Kujenga. Additionally, the corporation is on the cusp of investing in other agricultural projects, including soybeans, oil palms, palm kernel, and corn. ORL plans to reinforce rice cultivation by providing high-yield seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers to farmers under contract.

Kujenga’s major challenge in the coming years will be managing its economic system in a way that affords a greater proportion of its population access to affluence and a higher standard of living. The logical place to start is tackling corruption. In Kujenga, the poor do not benefit from the country’s wealth because of corruption and excessive influence that big business and the economic elite have over the formulation of government policy.

Trade

Prior to the post-independence mineral surge a half-century ago, agriculture was Kujenga’s largest export sector. Afterwards, the country’s economy became largely mineral-intensive and the agricultural sector faded in importance. Agricultural exports are currently at a low point because the recent drop in oil prices caused a dollar shortage, in turn creating pressure on local agribusinesses to increase their output to meet the domestic demand for food products.

Kujenga is currently unhindered by any international restrictions or sanctions that might adversely affect international trade participation.

Commercial Trade

Besides the dominant gemstone and industrial diamond trade, Kujenga exports mostly seafood, coffee, tea, spices, cocoa and rubber. The country’s major export partners are the United States, Spain, Ziwa, and Amari. Its major import partners are the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, and Olvana. Refined petroleum products, machinery, heavy equipment, consumer goods, and food products are Kujenga’s major imports.

Kujenga is a potentially lucrative market for adaptable companies willing to navigate a complex and evolving business environment. The country possesses abundant natural resources, cheap labor, and a youthful population (two-thirds under the age of 25). Rising incomes resulting from urbanization and consumer spending, which accounts for two-thirds of Kujenga’s GDP, are helping drive the economy forward. Young Kujengans are as tech-savvy as their American counterparts, and prospective foreign investors can expect substantial growth opportunities in information and communications technology, consumer goods, and the retail industry. Optimistic forecasts show growth in real estate development due to population increases, urban migration, and a rising middle class providing associated growth in the food and agriculture sectors, and infrastructure development.

Military Exports/Imports

Kujenga exports no significant quantities of hardware, logistical support items, or other services in the military category. Over the past five years, the country’s annual military expenditures were less than 0.5 percent of its GDP.

Meanwhile, analysts judge the country’s industrial base to be insufficient to meet the surge of maintenance, spare parts, and equipment upgrade needs associated with a major unexpected deployment or sustained expeditionary operation. Similarly, Kujenga’s current industrial base cannot underwrite significant military export trade. As a result, the country will be wholly dependent on external assistance.

Economic Diversity

Although mineral extraction can be a lucrative source of national income, it also makes the country vulnerable to fluctuations in the international commodities market. Largely for that reason, Kujenga’s main challenge in the economic arena is to diversify.

So far, economic diversification efforts and strong growth in the information and communications technology, services, and agricultural sectors have not significantly improved poverty levels, which now stand at over 70 percent.

Kujenga is far from achieving economic self-sufficiency. Lack of infrastructure—particularly in the transportation arena—is a major challenge to economic development, even as it presents a potential lucrative market attractive to foreign investors. Government reforms aimed at making Kujenga’s economy more entrepreneurial and business-friendly remain very much a work-in-progress, and are hampered by the persistent endemic corruption that pervades the national culture.

Energy Sector

Government authorities monitor the energy sector very closely because of recent natural gas finds in southeast Kujenga and along the Indian Ocean coast constitute a potential windfall of revenues and export earnings. The government jealously guards its prerogatives in controlling the exploitation and extraction of natural resources.

Despite huge potential reserves of natural gas, the energy sector is antiquated, primarily owing to inadequate infrastructure. The main inhibitors of progress include a shortage of port facilities capable of loading and unloading heavy cargoes and poorly maintained roads. The lack of a standardized record-keeping system is also a problem. Up-to-date corporate financial information is rarely available, and when available, is unreliable.

Oil

Kujenga’s modest crude oil reserves, like its natural gas reserves, are concentrated in the southeast quadrant of the country, near the border with Malawi and along the coast adjacent to the Indian Ocean. Most of Kujenga’s oil extraction occurs in offshore fields near its eastern coast. Conservative assessments place recoverable reserves at just over 1 billion barrels, with more optimistic figures double that. Most of the country’s oil exports are shipped to US and Western European markets, mainly because Kujenga lacks the pipeline and power-plant infrastructure required to support a robust domestic refining capacity. As a result, Kujenga does not produce enough fuel to meet its own domestic energy needs. Refined products must be imported for because Kujenga’s refining infrastructure is inadequate to meet local demand. The country's single refinery is currently only used as a storage terminal as it cannot economically compete with refined imports.

The government formerly centralized manufactured oil distribution in a vain effort to keep domestic prices at reasonable levels. More recently, as a result of government reforms aimed at spurring foreign investment in the oil industry, market dynamics caused short-term oil price increases, creating an oil theft problem. Because armed gangs establish roadblocks to “tax” large quantities of manufactured oil, many major oil companies sold drilling sites in Kujenga’s interior and relocated to offshore drilling sites.

Natural Gas