Difference between revisions of "Chapter 4: Defensive Operations"

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:TC|7-100.1-04]] |

| − | While the OPFOR sees the offense as the decisive form of military action, it recognizes defense as the stronger form of military action, particularly when faced with a superior, extraregional foe. Defensive operations can lead to strategic victory if the extraregional enemy abandons his mission. It may be sufficient for the OPFOR simply not to lose. Even when an operational-level | + | : ''This page is a section of [[FM 7-100.1 Opposing Forces Operations|FM 7-100.1 Opposing Forces Operations]].'' |

| + | While the OPFOR sees the offense as the decisive form of military action, it recognizes defense as the stronger form of military action, particularly when faced with a superior, extraregional foe. Defensive operations can lead to strategic victory if the extraregional enemy abandons his mission. It may be sufficient for the OPFOR simply not to lose. Even when an operational-level command—such as a field group (FG) or operational- strategic command (OSC)—as a whole is conducting an offensive operation, it is likely that one or more subordinate units may be executing defensive missions to preserve offensive combat power in other areas, to protect an important formation or resource, or to deny access to key facilities or geographic areas. | ||

| − | OPFOR defenses can be characterized as a “shield of blows.” Each force and zone of the defense plays an important role in the attack of the | + | OPFOR defenses can be characterized as a “shield of blows.” Each force and zone of the defense plays an important role in the attack of the enemy’s combat system. An operational-level defense is structured around the concept that destroying the synergy of the enemy’s combat system will make enemy forces vulnerable to attack and destruction. |

Commanders and staffs do not approach the defense with preconceived templates. The operational situation may cause the commander to vary his defensive methods and techniques. Nevertheless, there are basic characteristics of defensive operations (purposes and types of action) that have applications in all situations. | Commanders and staffs do not approach the defense with preconceived templates. The operational situation may cause the commander to vary his defensive methods and techniques. Nevertheless, there are basic characteristics of defensive operations (purposes and types of action) that have applications in all situations. | ||

| + | |||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

==Strategic Context== | ==Strategic Context== | ||

| − | + | Defensive operations are an important component of all OPFOR strategic campaigns. However, the scale and purpose of defensive actions may differ during the various types of strategic-level actions. | |

=== Regional Operations === | === Regional Operations === | ||

| − | + | The State possesses an overmatch in all elements of power against internal and regional opponents. It is able to employ that power in regional operations in a conventional operational design. This overmatch does not imply, however, that regional operations are entirely offensive. Consolidation of gains, security actions, and economy-of-force measures can all produce defensive courses of action inside a larger offensive design. | |

| − | + | The State’s military forces are sufficient to overmatch any single regional neighbor, but not necessarily an alliance or coalition of neighboring countries. They may not be a match for the forces an extraregional power can bring to bear. Thus, the OPFOR seeks to exploit its numerical and | |

| − | + | technological overmatch against one regional opponent rapidly, before other regional neighbors or an extraregional power can enter the fight. In some cases, this may require defensive operations against one or more regional neighbors who are not the main target of the strategic campaign, to mitigate their ability to disrupt an OPFOR offensive against the one that is. | |

| + | |||

| + | Regional operations include essentially defensive security actions to maintain internal stability. In addition, the Internal Security Forces help control the population in territory the OPFOR seizes or engage enemy forces that invade State territory. | ||

The State’s military goal during regional operations is to destroy its regional opponents’ military power in order to achieve specific ends. The State plans regional operations well in advance and executes them as rapidly as is feasible in order to preclude intervention by outside forces. Still, at the very outset of these operations, it lays plans and positions forces to conduct access-control operations in the event of outside intervention. Extraregional forces may also be vulnerable to conventional operations during the time they require to build combat power and create support at home for their intervention. | The State’s military goal during regional operations is to destroy its regional opponents’ military power in order to achieve specific ends. The State plans regional operations well in advance and executes them as rapidly as is feasible in order to preclude intervention by outside forces. Still, at the very outset of these operations, it lays plans and positions forces to conduct access-control operations in the event of outside intervention. Extraregional forces may also be vulnerable to conventional operations during the time they require to build combat power and create support at home for their intervention. | ||

| − | + | === Transition Operations === | |

| + | If an extraregional force starts to deploy into the region, the balance of power begins to shift away from the State. Although the OPFOR may not yet be totally overmatched by the enemy force, it faces a threat it cannot handle with normal, “conventional” patterns of operation designed for regional conflict. Therefore, the OPFOR must begin to adapt its operations to the changing threat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As the State begins transition operations, its immediate goal is preservation of its instruments of power while seeking transition back to regional operations. Transition operations therefore feature a mixture of offensive and defensive actions. | ||

| − | + | This combination of offensive and defensive actions can allow the State to control the strategic tempo while changing the nature of conflict to something for which the intervening force is unprepared. If these actions are successful and the extraregional force is no longer a factor, the OPFOR may be able to transition back to regional operations without having to complete the shift to adaptive operations. | |

| − | + | During transition operations, the State must decide whether to keep its forces in any territory it has occupied in a neighboring country or to withdraw them back to its home territory. The decision to stay or withdraw at this point may be based on the presence or absence of complex terrain suitable for defensive operations in the occupied territory against an extraregional power with overmatch in technology and conventional forces. The OPFOR is more likely to remain in the occupied territory if it has already achieved its strategic goal in regional operations or at least achieved major intermediate objectives leading toward that goal and can structure an effective defense in that territory. Military forces in the immediate vicinity of the point of intervention move into defensive positions as opportunity allows, making use of existing command and control (C2) and logistics. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | The OPFOR can use the time it takes the extraregional force to prepare and deploy into the region to change the nature of the conflict into something for which the intervening force is unprepared. The OPFOR tries to establish conditions that force the new enemy to fight at less than full strength and on terrain for which his forces are not optimized. It seeks to take advantage of complex terrain whenever possible, while controlling the enemy’s access to such terrain. It plans operations to exploit the opportunities created by the presence of NGOs, PVOs, media, and other civilians on the battlefield. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meanwhile, transition operations permit other key forces the time, space, and freedom of action necessary to move into sanctuary in preparation for a shift to adaptive operations. These forces preserve combat power and prepare to defend the State homeland, if necessary. Transition operations usually include mobilization of reserve and militia forces to assist in defending the State. | ||

| − | + | At some point, the OPFOR may conclude that it cannot deny entry or defeat the extraregional force by destroying his early-entry forces. The OPFOR then shifts its emphasis to completing the transition to adaptive operations as soon as possible, before the enemy can deploy overwhelming forces into the region. | |

| − | + | === Adaptive Operations === | |

| + | From the perspective of the extraregional power, any regional crisis has the potential to expand into a major theater war. Therefore, it will try to avoid crisis expansion by early engagement and rapid response. The longer the State can delay effective extraregional response to the crisis in the region, the greater its chances for success. Failing to limit or interrupt access to the region, the State will attempt to degrade further enemy force projection, hold initial gains, and extend the conflict, while preserving its own military capability and other instruments of national power. | ||

| − | + | When the OPFOR shifts to adaptive operations, these are more defensive in nature than were regional or transition operations. When overmatched in conventional power, the OPFOR seeks to preserve its own power and apply it in adaptive ways. It expects its commanders to seize opportunity, tailor organizations to the mission, and make creative use of existing resources—even more than they did in regional and transition operations. | |

| − | + | Generally, the OPFOR conducts adaptive operations during the strategic campaign as a consequence of intervention from outside the region. If it cannot control the extraregional enemy’s access into the region or defeat his forces before his combat potential in the region equals or exceeds its own, the OPFOR must resort to adaptive operations. The primary objectives are to preserve combat power, to degrade the enemy’s will and capability to fight, and to gain time for aggressive strategic operations to succeed. | |

| − | + | Adaptive operations occur as a result of an extraregional power intervening with sufficient forces to thwart the OPFOR’s original offensive operations in the region. The OPFOR disperses to the extent its C2 allows and conducts decentralized operations in both offense and defense. The OPFOR views adaptive operations as temporary in nature, serving as a means for the OPFOR to return to regional operations. | |

| − | + | Adaptive operations are often sanctuary-based. Sanctuaries are areas that limit the ability of an opponent to apply his full range of capabilities. The OPFOR can use physical and/or moral sanctuaries for preserving and applying forces. It can defend in sanctuaries or attack out of them. It may conduct limited-objective attacks from these positions to prevent buildup of intervening forces, to facilitate the defense, or to take advantage of an opportunity to counterattack. When defending, the OPFOR generally does not employ fixed, contiguous defensive fronts. | |

| − | |||

| − | During adaptive operations, the | + | The OPFOR uses flexible and unpredictable force structures task-organized for particular missions. Forces may be combined arms, joint, interagency, and possibly multinational. The State may fully mobilize all available means to create large conventional force and paramilitary capability in support of adaptive operations. Full mobilization involves all military and paramilitary forces, including militia. During adaptive operations, the State will use conventional forces in adaptive ways. It will also employ unconventional and specialized forces tailored to the needs of combat against an extraregional force with technological overmatch. Operations may also involve various types of affiliated forces. |

| − | + | == Purpose of the Defense == | |

| + | Defensive operations are designed to achieve the goals of the strategic campaign through active measures while preserving combat power. However, the purpose of any given defensive operation depends on the situation. | ||

| − | + | The primary distinction among types of OPFOR defensive operations is their purpose. Therefore, the OPFOR recognizes three general types of defensive operations according to their purpose: to destroy, preserve, or deny. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === Defense to Destroy === |

| − | + | A ''defense to destroy'' is designed to eliminate an attacking formation’s ability to continue offensive operations while preserving friendly forces and setting the military conditions for a favorable political settlement. Such a defense may be the entirety of an operation or may be used to defeat a counterattack during a larger OPFOR offensive action. An operational defense to destroy often has one or more tactical offensive actions as subcomponents. | |

| − | === | + | === Defense to Preserve === |

| − | + | A ''defense to preserve'' is designed to protect key components of the OPFOR from destruction by the enemy. Such a defense may occur— | |

| + | * To preserve combat power for future operations. | ||

| + | * Before the outbreak of a war, or in its early stages, to cover the mobilization and deployment of the main forces. | ||

| + | * When facing numerically or qualitatively superior enemy forces. | ||

| + | * During an offense, to economize force in one area and achieve superiority in another. | ||

| − | === | + | === Defense to Deny === |

| − | + | A ''defense to deny'' is intended to deny the enemy access to a geographic area or use of facilities that could enhance his combat operations or provide him substantial value for information operations. An example of this would be enemy capture of a religious or cultural center. This type of defense is most often used as part of an overall campaign of theater access control. It may also be used to consolidate, retain, and protect critical positions that attacking forces have captured. | |

| − | == Planning | + | == Planning Defensive Operations == |

| − | For the OPFOR, the key elements of planning | + | For the OPFOR, the key elements of planning defensive operations are— |

| − | * Determining the level of planning possible (planned versus situational | + | * Determining the level of planning possible (planned versus situational defense). |

* Organizing the battlefield. | * Organizing the battlefield. | ||

* Organizing forces. | * Organizing forces. | ||

| − | * Organizing IW activities (see Chapter 5). | + | * Organizing information warfare (IW) activities in support of the defense (see Chapter 5). |

| − | + | Defensive actions during transition and adaptive operations will not be able to rely simply on attrition-based operations in layered engagement areas. Such actions will typically include increased use of— | |

| − | + | * Infiltration to conduct spoiling attacks and ambushes. | |

| − | * Infiltration. | + | * Perception management (see Chapter 5) in support of defensive operations. |

| − | * Perception management (see Chapter 5) in support of operations. | + | * Camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D) measures. |

| − | * Affiliated forces | + | * Affiliated forces for reconnaissance, counterreconnaissance, security, and attacks against key enemy systems. |

| − | === Planned | + | === Planned Defense === |

| − | A ''planned'' (deliberate) | + | A ''planned'' (or ''deliberate'') defense is a defensive operation undertaken when there is sufficient time and knowledge of the situation to prepare and rehearse forces for specific tasks. Typically, the enemy is in a staging or assembly area and in a known location and status. The OPFOR plans a defense using the method described in Chapter 2. Key considerations in defensive planning are— |

| − | * Selecting | + | * Selecting operationally significant areas in complex terrain from which to dominate surrounding avenues of approach. |

| − | * Determining | + | * Determining the method that will deny the enemy his operational objectives. |

| − | * Developing a reconnaissance | + | * Developing a plan for reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) that locates and tracks major enemy formation and determines enemy patterns of operations and probable objectives. |

| − | * Creating or taking advantage of a window of opportunity | + | * Creating or taking advantage of a window of opportunity that frees friendly forces from any enemy advantages in precision standoff and situational awareness. |

| − | |||

| − | === Situational | + | === Situational Defense === |

| − | The OPFOR | + | The OPFOR recognizes that the modern battlefield is chaotic, and fleeting opportunities to attack an enemy weakness will continually present themselves and just as quickly disappear. If the OPFOR determines that, by conserving resources in one area, it may be able to take advantage of a window of opportunity in another, it may assume a ''situational'' (or ''hasty'') defense. It may also do so when an OPFOR attack culminates prior to achieving the objective. |

| − | The | + | The OPFOR may also be forced to employ a situational defense when it has been conducting offensive operations against a regional neighbor and intervention by a powerful extraregional force materializes more quickly than anticipated. Thus, the OPFOR may have to make the transition from regional to adaptive operations more rapidly than planned. Units may still be able to move into preplanned positions in complex terrain, but without some measures they anticipated being able to take during transition operations. They may or may not have fully-prepared, complex battle positions, with engineer preparation, C3D measures, and logistics caches. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The commander develops his assessment of the conditions leading to a situational defense rapidly and without a great deal of staff involvement. He provides a basic course of action to the staff, who then quickly turn that course of action into an executable operational directive. | |

| − | + | Organization of the battlefield in a situational defense is normally limited to minor changes to existing control measures. Organization of forces in a situational defense typically relies on minor modifications to existing structure. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The following are examples of conditions that might lead to a situational defense: | |

| − | + | * The enemy gains or regains air superiority sooner than anticipated. | |

| + | * An enemy counterattack was not effectively fixed. | ||

| + | * An attacking force makes contact with an enemy formation it did not expect. | ||

| − | + | === Organizing the Battlefield for the Defense === | |

| + | In his operation plan, the commander specifies the organization of the battlefield from the perspective of his level of command. Within his unit’s area of responsibility (AOR), as defined by the next-higher commander, he designates AORs for his subordinates, along with zones related to his own overall mission. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In organizing the defensive battlefield, the operational commander organizes forces to begin attack of the combat system of the enemy force as soon as feasible. By attacking subsystems or components of the enemy’s combat system appropriate to the situation, the operational commander can create windows of opportunity for offensive action. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===== Areas of Responsibility ===== | ||

| + | [[File:Figure 4-1. Example of AOR (Linear Battlespace).png|alt=Figure 4-1. Example of AOR (Linear Battlespace)|thumb|Figure 4-1. Example of AOR (Linear Battlespace)]] | ||

| + | [[File:Figure 4-2. Example of AOR (Nonlinear Battlespace).png|alt=Figure 4-2. Example of AOR (Nonlinear Battlespace)|thumb|Figure 4-2. Example of AOR (Nonlinear Battlespace)]] | ||

| + | OPFOR AORs normally consist of three principal ''zones'': disruption, battle, and support zones. Zones may be linear or nonlinear in nature and are designed to facilitate rapid transition between linear and nonlinear operations, as well as between offense and defense. These zones have the same basic purposes in all types of defenses. In addition to the basic zones in an AOR, the operational-level commander may also employ attack zones and kill zones to control subordinate offensive operations conducted in support of the overall defensive scheme. See Figures 4-1 and 4-2 for generalized examples of AORs and zones in linear and nonlinear defensive operations. | ||

==== Disruption Zone ==== | ==== Disruption Zone ==== | ||

| − | In the | + | In the defense, the ''disruption zone'' is that battlespace where operational forces begin their attack on the designated component or subsystem of the enemy’s combat system. It is located between the OSC’s battle zone and the limit of responsibility (LOR) that defines the extent of the AOR. Within this battlespace, the OPFOR seeks to set the conditions for the defeat of the attacking force in the battle zone. For example, the operational-level commander may determine that destruction of the enemy’s mobility assets will create an opportunity to destroy maneuver units in the battle zone. The disruption force would be given the mission of seeking out and destroying enemy mobility assets while avoiding engagement with maneuver forces. |

| − | The | + | The disruption zone is the primary area in which the operational-level commander will employ long-range joint fires and strikes. He may establish kill zones within his disruption zone for the purpose of integrating the actions of long-range fire elements and disruption force elements. |

| − | + | The operational-level disruption zone may be the aggregate of the disruption zones of subordinates. For example, an FG’s disruption zone could include the disruption zones of one or more OSCs and/or tactical-level commands directly subordinate to the FG. An OSC’s disruption zone could include disruption zones | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | of subordinate division and brigade tactical groups (DTGs and BTGs), although assets directly controlled by the OSC could also operate throughout an OSC disruption zone. In such cases, each subordinate would be responsible for a portion of the operational-level disruption zone, and that portion would constitute the subordinate’s disruption zone within its own AOR. In other cases, an operational-level disruption zone may extend beyond those of the FG’s or OSC’s subordinates, to include an area occupied by forces sent out under direct control of the FG or OSC commander. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Operational-level forces in the disruption zone could include special-purpose forces (SPF) and affiliated forces, which could be operating in enemy-held territory even before the beginning of hostilities. There could also be stay-behind forces in areas seized by the enemy. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==== Battle Zone ==== | ==== Battle Zone ==== | ||

| − | + | The ''battle zone'' is that battlespace in which the main defense force uses fires and maneuver to exploit the conditions created by successful disruption zone operations. In the battle zone, the main defense force completes the disaggregation of the enemy’s combat system by destroying the components exposed by the disruption force. By inflicting significant damage or denying the enemy his objectives, the main defense force causes the enemy to culminate and, in the best case, to quit the field entirely. An operational-level battle zone is often the aggregate of the battle zones of subordinate units. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | 4-40. The battle zone ties all available obstacles into an integrated fire support plan of all available weapons. It denies complex terrain to the enemy. It allows the enemy to enter easily, but to exit only at great cost or ideally not at all. The operational-level commander may establish kill zones within the battle zone for the purpose of integrating long-range fire, ground attack aviation, and main defense forces. Long-range fires from the battle zone may also reach kill zones in the disruption zone, where these fires can be integrated with the actions of disruption forces. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==== Support Zone ==== | ==== Support Zone ==== | ||

| − | The support zone is that area of the battlespace designed to be free of significant enemy action and to permit the effective logistics and administrative support of forces. Security forces operate in the support zone in a combat role to defeat enemy special operations forces and other threats. Camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D) measures throughout the support zone | + | The ''support zone'' is that area of the battlespace designed to be free of significant enemy action and to permit the effective logistics and administrative support of forces. Security forces (see Organizing Forces for the Defense below) operate in the support zone in a combat role to defeat enemy special operations forces and other threats. Camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D) measures occur throughout the support zone to protect the force from standoff RISTA and precision attack. |

==== Attack Zone ==== | ==== Attack Zone ==== | ||

| − | + | During an overall defensive operation, an ''attack zone'' may be employed to conduct an offensive action inside a larger defensive action. It will have the characteristics described in Chapter 3. An ''axis'' is a control measure showing the location through which a counterattack force, for example, will move as it proceeds from its assembly area to its attack zone. At the operational level, multi-division OSCs may conduct offensive actions as a part of a larger defensive scheme. | |

==== Kill Zone ==== | ==== Kill Zone ==== | ||

| − | A ''kill zone'' is a designated area on the battlefield where the OPFOR plans to destroy a key enemy target. Kill zones are tied to | + | A ''kill zone'' is a designated area on the battlefield where the OPFOR plans to destroy a key enemy target, usually by fire. Kill zones may be within any of the zones described above. |

| + | |||

| + | ==== Battle Position ==== | ||

| + | [[File:Figure 4-3. Battle Positions.png|alt=Figure 4-3. Battle Positions|thumb|Figure 4-3. Battle Positions]] | ||

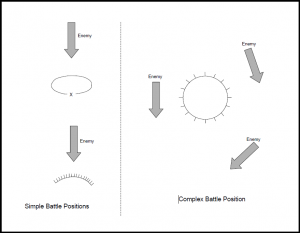

| + | Within the AOR of an operational command, tactical-level subordinates may occupy battle positions. A ''battle position'' is a defensive location designed to maximize the occupying unit’s ability to accomplish its mission. A battle position is selected such that the terrain in and around it is complementary to the occupying unit’s capabilities and its tactical task. There are two kinds of battle positions: simple and complex. See Figure 4-3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A ''simple battle position'' is a defensive location oriented on the most likely enemy avenue of approach. Simple battle positions are not necessarily tied to complex terrain but often employ as much engineer effort as time allows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Complex battle positions'' are defensive locations designed to protect the units within them from detection and attack while denying their seizure and occupation by the enemy. They typically employ a combination of complex terrain, C3D measures, and engineer effort to protect combat forces from engagement by precision standoff attack. | ||

| − | + | A typical complex battle position contains— | |

| − | + | * Complex terrain. | |

| + | * A substantial logistics cache. | ||

| + | * Extensive engineer fortification and obstacle work. | ||

| + | * C3D effort to confuse the enemy picture of strength and disposition. | ||

| + | * Precision fire capability. | ||

| + | * Mobile reserves. | ||

| + | * Air defense systems. | ||

| + | * Redundant C2 systems. | ||

| − | === Organizing Forces for the | + | === Organizing Forces for the Defense === |

| − | In | + | In his operation plan, the operational-level commander also specifies the organization of the forces within his level of command. Thus, subordinate forces understand their roles within the overall operation. However, the organization of forces can shift dramatically during the course of an operation. For example, a unit that initially was part of a disruption force may eventually occupy a battle position within the battle zone and become part of the main defense force or act as a reserve. |

| − | + | Each of the separate functional forces has an identified commander. This is often the senior commander of the largest subordinate unit assigned to that force. For example, if two DTGs and a separate BTG are acting as the OSC’s main defense force, the senior of the two DTG commanders is the main defense force commander. During decentralized operations, even when the force consists of like units of the same command level, control can be delegated to the senior commander of that force’s like units. Since, in this option, each force commander is also a subordinate unit commander, he controls the force from his unit’s command post (CP). | |

| − | + | Another option is to have one of the OSC’s or FG’s CPs be in charge of a functional force. Particularly during dispersed defensive operations, functional forces that contain units of the same command level might be controlled from the forward, auxiliary, or airborne CP of the OSC or FG. For example, the forward CP could control a disruption force. Another possibility would be for the IFC CP to command the disruption force or any other force whose actions must be closely coordinated with fires delivered by the integrated fires command (IFC). | |

| − | In any case, the force commander is responsible to the OSC or FG commander to ensure that combat preparations are made properly and to take charge of the force during the operation. This frees the operational-level commander from decisions specific to the force’s mission. Even when tactical-level subordinates of an OSC or FG have responsibility for parts of the disruption zone, there is still an overall OSC or FG disruption force commander. | + | In any case, the force commander is responsible to the OSC or FG commander to ensure that combat preparations are made properly and to take charge of the force during the operation. This frees the operational-level commander from decisions specific to the force’s mission. Even when tactical-level subordinates of an OSC or FG have responsibility for parts of the OSC or FG disruption zone, there is still an overall OSC or FG disruption force commander. |

==== Disruption Force ==== | ==== Disruption Force ==== | ||

| − | + | The size and composition of forces in the disruption zone depends on the level of command involved, the commander’s concept of operations, and the circumstances in which the unit adopts the defense. An operational-level disruption force has no set organization but may be as large as a multi-division OSC or consist only of SPF teams to direct reconnaissance fires and conduct direct action. The operational-level commander will always make maximum use of stay-behind forces and affiliated forces existing within his AOR. Subordinate commanders can employ forces in a disruption zone role independent of the operation plan only with approval of the operational-level commander. | |

| + | |||

| + | A disruption force has no set order of battle, but may contain— | ||

| + | * Ambush teams (ground and air defense). | ||

| + | * SPF teams. | ||

| + | * RISTA assets and forces. | ||

| + | * Counterreconnaissance forces. | ||

| + | * Artillery systems. | ||

| + | * Target designation teams. | ||

| + | * Affiliated forces (such as terrorists, insurgents, criminals, or special police). | ||

| + | * Antilanding reserves. | ||

| + | The purpose of the disruption force is to prevent the enemy from conducting an effective attack. The disruption force does this by initiating the attack on components of the enemy’s combat system. Successful attack of designated components or subsystems begins the disaggregation of the enemy’s combat system and creates vulnerabilities for exploitation in the battle zone. Skillfully conducted disruption operations will effectively deny the enemy the synergy of effects of his combat system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The disruption force may also have a counterreconnaissance mission. It may selectively destroy or render irrelevant the enemy’s RISTA forces. There will be times, however, when the OPFOR wants enemy reconnaissance to detect something that is part of the deception plan. In those cases, the disruption force will not seek to destroy all of the enemy’s RISTA assets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Main Defense Force ==== | ||

| + | The ''main defense force'' is the component of the operational-level command that is charged with execution of the defensive mission. It operates in the battle zone to accomplish the purpose of the operation (destroy, preserve, or deny). | ||

| − | ==== | + | ==== Protected Force ==== |

| − | + | In a defense to preserve, the ''protected force'' is the force being kept from detection or destruction by the enemy. Protection can be afforded by C3D and/or the actions of other OPFOR units. There is generally some force that the OPFOR is trying to protect from enemy observation and fire, to ensure that it will still have that force after the current operation is over. At the operational level, this force is critical to future operations and the preservation of the regime. It may be in the battle zone or the support zone. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==== | + | ==== Security Force ==== |

| − | The | + | The ''security force'' conducts activities to prevent or mitigate the effects of hostile actions against the overall operational-level command and/or its key components. If the commander chooses, he may charge this security force with providing force protection for the entire AOR, including the rest of the functional forces; logistics and administrative elements in the support zone; and other key installations, facilities, and resources. The security force may include various types of units—such as infantry, SPF, counterreconnaissance, and signals reconnaissance assets—to focus on enemy special operations and long-range reconnaissance forces operating throughout the AOR. It can also include internal security forces units allocated to the operational-level command, with the mission of protecting the overall command from attack by hostile insurgents, terrorists, and special operations forces. The security force may also be charged with mitigating the effects of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). The security force commander can be given control over one or more reserve formations, such as the antilanding reserve. |

| − | '' | + | ==== Counterattack Forces ==== |

| + | In a defensive operation with a planned counterattack scheme (typically in a maneuver defense), the operational-level commander designates one or more ''counterattack forces''. He also shifts his task organization to create a counterattack force when a window of opportunity opens that leaves the enemy vulnerable to such an action. At the operational level, the counterattack force may be a multi-division force with the mission to destroy a major enemy formation that is exposed. The operational-level commander uses counterattack forces to complete the defensive mission assigned and regain the initiative for the offense. The counterattack force can have within it fixing, assault, and exploitation forces (as outlined in Chapter 3). | ||

| − | + | Types of Reserves | |

| − | + | At the commander’s discretion, forces may be held out of initial action so that he may influence unforeseen events or take advantage of developing opportunities. He may employ a number of different types of reserve forces of varying strengths, depending on the situation. | |

| − | + | '''Maneuver Reserve.''' The size and composition of a reserve force is entirely situation-dependent. However, the reserve is normally a force strong enough to respond to unforeseen opportunities and contingencies at the operational level. A reserve may assume the role of counterattack force to deliver the final blow that ensures the enemy can no longer conduct his preferred operation. | |

| + | |||

| + | A reserve force is given a list of possible missions for rehearsal and planning purposes. The staff assigns to each of these missions a priority, based on likelihood that the reserve might be called upon to execute that mission. Some missions given to the reserve may include— | ||

| + | * Conducting a counterattack. (The counterattack goal is not limited to destroying enemy forces, but may also include recovering lost positions or capturing positions operationally advantageous for subsequent combat actions.) | ||

| + | * Conducting counterpenatration (blocking or destroying enemy penetrations). | ||

| + | * Conducting antilanding operations (eliminating vertical envelopments). | ||

| + | * Assisting forces heavily engaged on a defended line to break contact and withdraw. | ||

| + | * Act as a deception force. | ||

| + | '''Antitank Reserve.''' OPFOR commanders faced with significant armored threats may keep an antitank reserve (ATR). It is generally an anti-tank unit and often operates in conjunction with an obstacle detachment (OD). Based on the availability of antitank and engineer assets, an operational-level command may form more than one ATR. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Antilanding Reserve.''' Because of the potential threat from enemy airborne or airmobile troops, an operational-level commander may designate an antilanding reserve (ALR). Operational-level ALRs would be resourced for rapid movement to potential drop zones (DZs) and landing zones (LZs). The ALR commander would have immediate access to the operational intelligence system for early warning of potential enemy landing operations. ALRs typically include maneuver forces, air defense assets, and engineer units, but may be allocated any unit capable of disrupting or defeating an airborne or heliborne landing, such as smoke or electronic warfare (EW). While other reserves can perform this mission, the commander may create a dedicated ALR to prevent destabilization of the defense by vertical envelopment of OPFOR units or seizure of key terrain. ALRs assume positions prepared to engage the enemy primary DZ or LZ as a kill zone. They rehearse and plan for rapid redeployment to other suspected DZs or LZs. Operational-level commanders may direct long-range fires or SPF direct action to prevent enemy forces from mounting air insertions. The destruction of airframes or fuel sources, or the positioning of air defense assets may serve to take this option away from enemy forces. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Special Reserves.''' An operational-level command may form an ''engineer reserve'' of earthmoving and obstacle-creating equipment. A commander can deploy this reserve to strengthen defenses on a particularly threatened axis during the course of the operation. An operational-level command threatened by enemy use of WMD may also form a ''chemical defense reserve''. | ||

==== Deception Force ==== | ==== Deception Force ==== | ||

| − | When the IW plan requires | + | When the IW plan requires the creation of nonexistent or partially existing formations, these forces are designated ''deception forces'' in close-hold executive summaries of the operation plan. Wide-distribution copies of the plan make reference to these forces according to the designation given them in the deception story. The deception force in the defense is typically given its own command structure to both replicate the organization(s) necessary to the deception story and to execute the multidiscipline deception required to replicate an actual military organization. For example, FG commanders can use deception OSC command structures to deny enemy forces information on operation plans for the defense. |

| − | + | == Preparing for the Defense == | |

| + | In the preparation phase, the OPFOR focuses on ways of applying all available resources and the full range of actions to conduct defensive operations. Commanders organize their forces and the battlefield with an eye toward capitalizing on conditions created by successful defensive actions, and seizing opportunities for offensive actions wherever possible. The defensive dispositions are based on the application of the systems warfare approach to combat, as described in Chapter 1. OPFOR defensive operations focus on attacking components or subsystems to of the enemy’s combat system to disaggregate the “system of systems.” By denying the enemy the synergy created by an integrated, aggregated system, vulnerabilities are created that defensive forces can exploit. | ||

| − | + | === Deny Enemy Information === | |

| + | Operational-level commanders realize that enemy operations hinge on an appreciation of the situation. So, defensive preparations focus on destruction and deception of enemy national and theater sensors. Lethal and nonlethal attack of enemy intelligence satellites and reconnaissance aircraft can limit the ability of enemy forces to understand the OPFOR defensive plan. The OPFOR recognizes that, when conducting operations against an extraregional power, it will often be impossible to destroy the ability of the enemy’s standoff RISTA means to observe its defensive preparations. However, the OPFOR also recognizes the reluctance of enemy military commanders to operate without human confirmation of intelligence, as well as the relative ease with which imagery and signals sensors may be deceived. The OPFOR operational-level commander considers ground reconnaissance by enemy special operations Forces as a significant threat in the enemy RISTA suite and focuses significant effort to ensure its removal. While the OPFOR will execute missions to destroy standoff RISTA means, C3D would be the method of choice for degrading the capability of such systems. | ||

| − | == | + | === Make Thorough Countermobility and Survivability Preparations === |

| − | + | The more time available, the greater the preparation of an AOR for the defense. This is a reflection of engineer effort and time to devote to that effort. The OPFOR employs every method to maximize the time available to prepare for the defense. This includes preparation of the State during peacetime and highly detailed plans for transition from regional to adaptive operations to take full advantage of any operational lull as the enemy builds combat power. This might involve an offensive operation with limited objectives that transitions to the defense by design. | |

| − | + | Operational-level commanders realize that engineer works are vital to the stability of the defense. Engineer assets will be used to improve the advantages of complex terrain in protecting friendly forces and exposing enemy forces to engagement. Engineer efforts can contribute to creating windows of opportunity by degrading the ability of the enemy’s combat system to integrate the effects of its subsystems. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | Engineer units specializing in rapid obstacle construction and minelaying form mission-specific units known as ODs. These ODs normally deploy in conjunction with reserves to block enemy penetrations or to protect the flanks of counterattack forces. In the initial stages of the defense, engineer assets concentrate on creating obstacles in the disruption zone, in gaps in the combat formation, and to the flanks, and preparing lines for counterpenetration and counterattack and routes to such lines. The obstacle plan ensures that the effort is coordinated with fires and maneuver to produce the desired effects. In conjunction with other tasks, engineers support the IW plan through activities such as constructing false defensive positions and preparing false routes. More information on countermobility and survivability planning at the operational level can be found in Chapter 10. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Make Use of Complex Terrain === | ||

| + | The OPFOR tries to make maximum use of complex terrain in all defensive operations. Complex terrain provides cover from fires, concealment from standoff RISTA assets, and intelligence and logistics support from the population of urban areas. It plays into the strength of OPFOR resolve to win through any means and through protracted conflict if necessary. | ||

=== Make Thorough Logistics Arrangements === | === Make Thorough Logistics Arrangements === | ||

| − | The OPFOR understands that there is as much chance of | + | The overwhelming ability of extraregional intervention forces to attack exposed logistics elements makes it difficult to resupply forces. The OPFOR understands that there is as much chance of a defensive operation being brought to culmination by a lack of sufficient logistics support as there is by enemy action. Careful consideration is given to carried days of supply and pre-established caches to obviate the need for easily disrupted lines of communication (LOCs). |

=== Modify the Plan When Necessary === | === Modify the Plan When Necessary === | ||

The OPFOR takes into account that, while it might consider itself to be in the preparation phase for one operation, it is continuously in the execution phase. Plans are never considered final. Plans are checked throughout the course of their development to ensure they are still valid in light of battlefield events. | The OPFOR takes into account that, while it might consider itself to be in the preparation phase for one operation, it is continuously in the execution phase. Plans are never considered final. Plans are checked throughout the course of their development to ensure they are still valid in light of battlefield events. | ||

| − | + | Rehearse Everything Possible, In Priority | |

| − | |||

| − | + | At the operational level, rehearsals are usually confined to map or sand table exercises to ensure understanding by subordinate commanders. The commander establishes the priority for critical parts of the operation, and rehearses those operations with his subordinates. Typical actions to be rehearsed in a defensive operation include— | |

| − | The | + | * Commitment of a reserve. |

| + | * Initiation of a counterattack. | ||

| + | * Execution of the fire support plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Executing the Defense === | ||

| + | Successful execution depends on forces that understand their roles in the operation and can swiftly follow preparatory actions with implementation of the operation plan or rapid modifications to the plan, as the situation requires. A successful execution phase results in the culmination of the enemy’s offensive action. It ideally ends with transition to the offense in order to keep the enemy under pressure and destroy him completely. During adaptive operations against superior enemy force, however, a successful defense may end in a stalemate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A successful operational-level defense sets the military conditions for a return to the offense or a favorable political resolution of the conflict. The OPFOR may have to surrender territory to preserve forces. Territory can always be recaptured, but the destruction of OPFOR operational formations threatens the survival of the State. Destruction of the protected force is unacceptable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Success criteria for an operational-level commander conducting an area or maneuver defense may include— | ||

| + | * Major combat formations remain intact. | ||

| + | * The enemy is forced to withdraw or, at a minimum, forego offensive operations due to losses. | ||

| + | * A stalemate allows theater- and national-level assets time to conduct attacks against enemy strategic centers of gravity. | ||

=== Maintain Contact === | === Maintain Contact === | ||

| − | + | OPFOR operational-level commanders go to great lengths to maintain contact with enemy formations and headquarters that may influence theater operations. This includes rapid reconstitution of reconnaissance assets and forces. | |

=== Modify the Plan When Necessary === | === Modify the Plan When Necessary === | ||

| − | The OPFOR is sensitive to the effects of mission dynamics and realizes that the enemy’s actions may well make an OPFOR | + | The OPFOR is sensitive to the effects of mission dynamics and realizes that the enemy’s actions may well make the original mission of an OPFOR unit achievable, but completely irrelevant. As an example, an OSC assigned a mission to secure a critical area or facility may find that mission is not viable if the enemy conducts a major air insertion that threatens the overall defensive plan. Parts of that OSC may be called upon to initiate limited offensive action while the air insertion is still vulnerable. |

=== Seize Opportunities === | === Seize Opportunities === | ||

The OPFOR places maximum emphasis on decentralized execution, initiative, and adaptation. Subordinate units are expected to take advantage of fleeting opportunities so long as their actions are in concert with the purpose of the operational directive. | The OPFOR places maximum emphasis on decentralized execution, initiative, and adaptation. Subordinate units are expected to take advantage of fleeting opportunities so long as their actions are in concert with the purpose of the operational directive. | ||

| − | === | + | == Integrated and Decentralized Defenses == |

| − | + | The OPFOR recognizes two general forms of defense: integrated and decentralized. The distinction between the two rests on the ability of the OPFOR to operate freely in the battlespace with full joint and combined arms synchronization and adequate C2 and logistics support. | |

| − | == | + | === Integrated Defense === |

| − | + | A defensive operation is ''integrated'' if the OPFOR has the ability to achieve full joint and/or combined arms synchronization through all levels of command and throughout the battlespace. This requires a modernized C2 system, a robust logistics capability, and the ability to operate relatively free of enemy influence in the support zone and battle zones prior to the commencement of full-fledged enemy offensive action. The OPFOR force structure possesses the first two of these characteristics, at least in relation to regional opponents. Thus, during regional operations and perhaps transition operations, it would often be operating in an integrated fashion unless the enemy is able to achieve a sufficient level of overmatch in RISTA and standoff attack capability to deny the OPFOR freedom of action. | |

| − | + | 4-84. Integrated defenses are able to— | |

| − | + | * Operate, at least partially, without the requirement for windows of opportunity. | |

| + | * Maximize the effects of destructive fire and maneuver. | ||

| + | * Achieve operational decision through primarily military means. | ||

| − | + | === Decentralized Defense === | |

| + | A defensive operation is ''decentralized'' if the OPFOR’s C2 and/or logis- tics capability has been significantly degraded or it does not have the ability to operate freely in the battlespace. This typically occurs when the enemy en- joys significant technological overmatch, particularly in technical RISTA means and standoff precision attack. Decentralized defenses do not achieve decision in and of themselves. Rather, they focus on preserving combat power while buying time for the execution of strategic operations (see Chapter 1). | ||

| − | + | In some cases, an operational-level commander may chose to adopt a decentralized defense to preserve his C2 and logistics, understanding that his ability to synchronize operations will be degraded. Operational-level commanders are constantly estimating the situation to determine risk versus reward for active measures. A decentralized defense relies on initiative of subordinate commanders and the discrete targeting of elements of the enemy’s combat system to reduce combat capability and expose enemy forces to destruction. | |

| − | + | To be successful, decentralized defenses must— | |

| − | + | * Operate primarily in complex terrain. | |

| + | * Maximize the effects of countermobility and survivability measures. | ||

| + | * Rely heavily on IW. | ||

| + | * Make the best possible use of reconnaissance fires (see Chapter 7). | ||

| − | The | + | == Types of Defensive Action == |

| + | The types of defensive action in OPFOR doctrine are both tactical methods and guides to the design of operational courses of action. The two basic types are maneuver and area defense. An operational-level defensive plan may include subordinate units that are executing various combinations of maneuver and area defenses, along with some offensive courses of action, within the overall defensive mission framework. | ||

| − | + | === Maneuver Defense === | |

| − | + | In situations where the OPFOR is not completely overmatched, it may conduct an operational ''maneuver defense''. This type of defense is designed to achieve operational decision by skillfully using fires and maneuver to destroy key components of the enemy’s combat system and deny enemy forces their objective, while preserving the friendly force. Maneuver defenses cause the enemy to continually lose effectiveness until he can no longer achieve his objectives. They can also economize force in less important areas while the OPFOR moves additional forces onto the most threatened axes. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Maneuver defenses are almost always integrated defenses. Decentralized maneuver defenses typically occur as part of transition operations. As an extraregional enemy builds combat power to overmatch levels, but before the OPFOR is completely overmatched, maneuver defense can buy time for other forces to move into sanctuary areas and prepare for adaptive operations. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Even within a maneuver defense, the OPFOR may use area defense on some enemy attack axes, especially on those where it can least afford to lose ground. (See Figure 4-1.) An operational-level commander may use both forms of defense simultaneously across the theater. A command may employ maneuver defense techniques to conduct operations in the disruption zone if it enhances the attack on the enemy’s combat system and an area defense in the battle zone. | |

| − | + | ==== MethodFigure 4-5. Maneuver Defense (Example 2) ==== | |

| + | [[File:Figure 4-4. Maneuver Defense (Example 1).png|alt=Figure 4-4. Maneuver Defense (Example 1)|thumb|Figure 4-4. Maneuver Defense (Example 1)]] | ||

| + | Maneuver defense inflicts losses on the enemy, gains time, and protects friendly forces. It allows the operational defender to choose the place and time for engagements. Each portion of a maneuver defense allows a continuing attack on the enemy’s combat system. As the system begins to disaggregate, more elements are vulnerable to destruction. The maneuver defense accomplishes this through a succession of defensive battles in conjunction with short, violent counterattacks and fires. It allows abandoning some areas of terrain when responding to an unexpected enemy attack or when conducting the battle in the disruption zone. In the course of a maneuver defense, the operational-level commander tries to force the enemy into a situation that exposes enemy formations to destruction. See Figures 4-4 and 4-5 for examples of maneuver defense. | ||

| − | + | A maneuver defense trades terrain for the opportunity to destroy portions of the enemy formation and render the enemy’s combat system ineffective. The OPFOR might use a maneuver defense when— | |

| + | * It can afford to surrender territory. | ||

| + | * It possesses a mobility advantage over enemy forces. | ||

| + | * Conditions are suitable for canalizing the enemy into areas where the OPFOR can destroy him by fire or deliver decisive counterattacks. | ||

| + | Compared to area defense, the maneuver defense involves a higher degree of risk for the OPFOR, because it does not rely heavily on the inherent advantages of prepared defensive positions. Units conducting a maneuver defense typically place smaller forces forward in defensive positions and retain much larger reserves than in an area defense. | ||

| − | ==== | + | ===== Defensive Lines ===== |

| − | '' | + | The basis of maneuver defense is for units to conduct maneuver from position to position on a succession of ''defensive lines.'' In this case, the “line” defended on is not a continuous line of defenses, but rather a notional line on which one or more units have orders to defend for a certain time at a certain depth within a unit’s AOR. The OPFOR accepts large intervals between defensive positions on such a line. Part of the line may consist of natural or manmade obstacles or of deception defensive positions. |

| − | + | These “lines” are not necessarily linear, in the sense of forming a straight line. Nor are they necessarily at regular intervals from one another. | |

| − | + | A particular unit’s position on a subsequent line may not be directly behind its previous position. In the spaces between the lines, the defenders can organize reconnaissance fire, raids, and counterattacks. Thus, it is difficult for the enemy to predict where he will encounter resistance. | |

| + | [[File:Figure 4-5. Maneuver Defense (Example 2).png|alt=Figure 4-5. Maneuver Defense (Example 2)|thumb|Figure 4-5. Maneuver Defense (Example 2)]] | ||

| + | The number of lines and duration of defense on each line depend on the nature of the enemy’s actions, the terrain, and the condition of the defending units. Lines are selected based on the availability of natural obstacles and shielding terrain, with consideration of being able to leave the lines without being observed. | ||

| − | + | '''Defensive Maneuver''' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Defensive maneuver'' consists of movement by bounds and the maintenance of continuous fires on enemy forces. A disruption force and/or a main defense force (or part of it) can perform defensive maneuver. In either case, the force must divide its combat power into two smaller components: a contact force and a shielding force. The ''contact force'' is the component occupying the forward-most defensive line at any point in time. The ''shielding force'' is the component occupying the next line immediately to the rear. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | At each line, the contact force ideally forces the enemy to deploy his maneuver units and perhaps begin his artillery preparation for the attack. Then, before the contact force becomes decisively engaged, it maneuvers to its next preplanned line, behind the line occupied by the shielding force. While the original contact force is moving, the shielding force is able to keep the enemy under continuous fires. When the original contact force passes to the rear of the original shielding force, the latter force becomes the new contact force. When the original contact force occupies its next line, it becomes the shielding force for the new contact force. In this manner, units continue to move by bounds to successive lines, preserving their own forces while delaying and destroying the enemy. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Figures 4-1, 4-4, and 4-5, due to the operational scope of the overall maneuver defense shown, depict only the general location of a BTG or DTG as it moves to subsequent positions. These figures do not reflect the reality that the contact and shielding forces moving by bounds are likely to be detachments within a BTG or DTG. See FM 7-100.2 for examples of how this process works at the tactical level. | |

| − | + | Subsequent lines are far enough apart to permit defensive maneuver by friendly units. The distance should also preclude the enemy from engaging one line and then the other without displacing his indirect fire weapons. This means that the enemy, having seized one line, must change the majority of his firing positions and organized his attack all over again in order to get to the next line. However, the lines are close enough to allow the defending units to maintain coordinated, continuous fires on the enemy while moving from one to the other. | |

| − | + | OPFOR commanders may require a unit holding a line to continue defending, even if this means it becomes decisively engaged or enveloped. This may be necessary in order to allow the construction of defenses to the rear of the line this unit is defending. | |

| − | === | + | ===== Disruption Force ===== |

| − | + | An operational-level defense may have an OSC occupying an operational disruption zone if it is important to delay enemy forces to allow theater transition to adaptive operations. The task organization of such an OSC would have sufficient mobility to conduct a maneuver defense and a significant allocation of artillery and rocket units. The disruption force initiates the attack on the enemy’s combat system by targeting and destroying subsystems that are critical to the enemy. If successful, the disruption force can cause culmination of the enemy attack before the enemy enters the battle zone. In the worst case, the enemy would enter the battle zone unable to benefit from an integrated combat system and vulnerable to defeat by the main defense force. | |

| − | The | + | Forces committed to the disruption zone battle for an OSC usually would be a BTG or DTG, along with supporting and affiliated assets from the OSC. The OSC conducts the defense throughout the depth of the disruption zone. Maneuver units conduct the defense from successive battle positions. Intervals between these positions provide space for deployment of mobile attack forces, precision fire systems, and reserves. |

| − | + | The distance between successive positions in the disruption zone is such that the enemy is forced to displace the majority of his supporting weapons to continue the attack on the subsequent positions. This aids the force in breaking contact and permits time to occupy subsequent positions. Long-range fires, ODs, and ambushes to delay pursuing enemy units can assist units in breaking contact and withdrawing. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | If the disruption force has not succeeded in destroying or halting the attacking enemy, but is not under too great a pressure from a pursuing enemy, it may occupy prepared battle positions in the battle zone and assist in the remainder of the defensive mission as part of the main defense force. A disruption force may have taken losses and might not be at full capability; a heavily damaged disruption force may pass into hide positions. In that case, main defense or reserve forces occupy positions to cover the disruption force’s disengagement. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===== Main Defense Force ===== | |

| + | The mission of the main defense force is complete the defeat of the enemy by attack of those portions of the force exposed by disruption zone operations. In a multi-OSC operation, this may involve resubordination of units and in some cases attacks by fire or maneuver forces across OSC limits of responsibility. | ||

| − | + | The main defense force in a maneuver defense divides its combat power into contact and shielding forces. These forces move in bounds to successive defensive lines. If maneuver defense in the disruption zone has provided sufficient time, the defensive positions on these lines may take on more of the characteristics of prepared battle positions. | |

| − | + | The basic elements of the battle zone are battle positions, firing lines, and repositioning routes. Battle positions use the terrain to protect forces while providing advantage in engagements. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The commander may order a particular unit to stand and fight on a line long enough to repel an attack. He may order this if circumstances are favorable for defeating the enemy at that line. The unit also might have to remain on that line because the next line is still being prepared or a vertical envelopment threatens the next line or the route to it. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===== Reserves ===== | |

| + | An operational-level command in the maneuver defense can employ a number of reserve forces of varying strengths. The maneuver reserve is a force strong enough to respond to unforeseen opportunities and contingencies at the operational level. It is normally strong enough to defeat the enemy’s exploitation force. The commander positions this reserve in an assembly area using C3D to protect it from observation and attack. From this position, it can transition to a situational defense or conduct a counterattack. The reserve must have sufficient air defense coverage to allow maneuver. If the commander does not commit the reserve from its original assembly area, it maneuvers to another assembly area, possibly on a different axis, where it prepares for other contingencies. (See the Reserves section above for discussion of other types of reserves.) | ||

| − | + | === Area Defense === | |

| − | + | In situations where the OPFOR must deny geographic areas (or the access to them) or where it is overmatched, it may conduct an operational ''area defense''. An area defense uses complex battle positions to protect key components of the OPFOR’s combat power while creating opportunities, if possible, to attack the enemy’s combat system. Not every component of OPFOR combat power needs to or will be able to operate from complex battle positions. However, those components most central for the OPFOR commander’s plan will be the priority for preservation. Area defense is designed to achieve a decision in one of two ways: | |

| − | + | * By forcing the enemy’s offensive operations to culminate before he can achieve his objectives. | |

| − | + | * By denying the enemy his objectives while preserving combat power until decision can be achieved through strategic operations (see Chapter 1) | |

| − | + | [[File:Figure 4-6. Area Defense (Example 1).png|alt=Figure 4-6. Area Defense (Example 1)|thumb|Figure 4-6. Area Defense (Example 1)]] | |

| − | + | [[File:Figure 4-7. Area Defense (Example 2).png|alt=Figure 4-7. Area Defense (Example 2)|thumb|Figure 4-7. Area Defense (Example 2)]] | |

| − | * | + | See Figures 4-6 and 4-7 for examples of area defense. |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The area defense does not surrender the initiative to the attacking forces, but takes action to create windows of opportunity that permit forces to conduct small-scale offensive actions to attack key components of the enemy combat system and cause unacceptable casualties. Area defense can set the conditions for destroying a key enemy force in a strike. Extended windows of opportunity permit the action of maneuver forces and facilitate transition to a larger offensive action. IW is particularly important to the execution of the area defense in adaptive and transition operations. Deception is critical to the creation of complex battle positions, and effective perception management is vital to the creation of the windows of opportunity needed to execute maneuver and fires. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==== Method ==== | |

| − | + | Area defense inflicts losses on the enemy, retains ground, and protects friendly forces. It does so by occupying battle positions in complex terrain and dominating the surrounding battlespace with reconnaissance fire (see Chapter 7). These fires attack designated elements of the enemy’s combat system to destroy components and subsystems that create an advantage for the enemy. The operational design of an area defense is to begin disaggregating the enemy’s combat system in the disruption zone. When enemy forces enter the battle zone, they should be incapable of synchronizing combat operations. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Area defense creates windows of opportunity in which to conduct spoiling attacks or counterattacks and destroy key enemy systems. In the course of an area defense, the operational-level commander uses terrain that exposes the enemy to continuing attack. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | An area defense trades time for the opportunity to attack enemy forces when and where they are vulnerable. The OPFOR might use an area defense when— | |

| + | * It is conducting access-control operations. | ||

| + | * Enemy forces enjoy a significant RISTA and precision standoff advantage. | ||

| + | * Conditions are suitable for canalizing the enemy into areas where the OPFOR can destroy him by fire and/or maneuver. | ||

| + | A skillfully conducted area defense can allow a significantly weaker force to defeat a stronger enemy force. However, the area defense relies to a significant degree on the availability of complex terrain and decentralized logistics. Units conducting an area defense typically place small ambushing and raiding forces in complex terrain throughout the AOR to force the enemy into continuous operations and steadily drain his combat power and resolve. | ||

| − | + | Within an overall operational area defense, the OPFOR might use maneuver defense on some portions of the AOR, especially on those where it can afford to lose ground. This occurs most often during transition operations as forces initially occupy the complex terrain positions necessary for the execution of the area defense. | |

| − | + | ==== Disruption Force ==== | |

| + | In an area defense, the disruption zone is that battlespace surrounding its battle zone(s) where the OPFOR may cause continuing harm to the enemy without significantly exposing itself. For example, counterreconnaissance activity may draw the attention of enemy forces and cause them to enter the kill zone of a sophisticated ambush using long-range precision fires. RISTA assets and counterreconnaissance forces occupy the disruption zone, along with affiliated forces. Paramilitary forces may assist other disruption force units by providing force protection, controlling the civilian population, and executing deception operations as directed. | ||

| − | + | The disruption zone of an area defense is designed to be an area of uninterrupted battle. OPFOR RISTA maintains contact with enemy forces, and other parts of the disruption force attack them incessantly with ambush and precision fires. | |

| − | + | The disruption force has many missions. The most important mission at the operational level is the destruction of appropriate elements of the enemy’s combat system, to begin disaggregating it. The following list provides examples of other tasks that the disruption force may perform: | |

| − | + | * Detect the enemy’s main groupings. | |

| + | * Force the enemy to reveal his intentions. | ||

| + | * Deceive the enemy as to the location and configuration of battle positions. | ||

| + | * Delay the enemy, allowing time for preparation of defenses and counterattacks. | ||

| + | * Force the enemy into premature deployment. | ||

| + | * Attack lucrative targets (key systems, vulnerable troops). | ||

| + | * Canalize the enemy into situations unfavorable to him. | ||

| + | The disruption force mission also includes maintaining contact with the enemy and setting the conditions for successful reconnaissance fire and strikes. | ||

| − | + | In an area defense, the disruption force often occupies and operates out of battle positions in the disruption zone and seeks to inflict maximum harm on selected enemy units and destroy enemy systems operating throughout the AOR. An area defense disruption force permits the enemy no safe haven and continues to inflict damage at all hours and in all weather conditions. | |

| − | + | Disruption force units break contact after conducting ambushes and return to battle positions for refit and resupply. Long-range fires, ODs, and ambushes to delay pursuing enemy units can assist units in breaking contact and withdrawing. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Even within the overall context of an operational area defense, the disruption force might employ a maneuver defense. In this case, the distance between positions in the disruption zone is such that the enemy is forced to displace the majority of his supporting weapons to continue the attack on the subsequent positions. This aids the force in breaking contact and permits time to occupy subsequent positions. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The disruption zone often includes a significant obstacle effort. Engineer effort in the disruption zone also provides mobility support to disruption force units requiring maneuver to conduct their attacks or ambushes. | |

| − | + | Within the overall structure of the area defense, disruption force units seek to conduct highly damaging local attacks. They deploy on likely enemy avenues of approach. They choose the best terrain to inflict maximum damage on the attacking enemy and use obstacles and barriers extensively. They defend aggressively by fire and maneuver. When enemy pressure grows too strong, these forces can conduct a maneuver defense, withdrawing from one position to another in order to avoid envelopment or decisive engagement. | |

| + | |||

| + | Since a part of the disruption force mission to attack the enemy’s combat system, the following are typical targets for attack: | ||

| + | * C2 systems. | ||

| + | * RISTA assets. | ||

| + | * Precision fire systems. | ||

| + | * Aviation assets in the air and on the ground—at attack helicopter forward arming and refueling points (FARPs) and airfields. | ||

| + | * Logistics support areas. | ||

| + | * LOCs. | ||

| + | * Mobility and countermobility assets. | ||

| + | * Casualty evacuation routes and means. | ||

| + | In some cases, the disruption force can have a single mission of detecting and destroying a particular set of enemy capabilities. This does not mean that no other targets will be engaged; it means that, given a choice between targets, the disruption force will engage the targets that are the most damaging to the enemy combat system. | ||

| − | + | ===== Main Defense Force ===== | |

| + | The units of the main defense force conducting an area defense occupy battle positions in complex terrain within the battle zone. That terrain is reinforced by engineer effort and C3D measures. These complex battle positions are designed to prevent enemy forces from being able to employ precision standoff attack means and force the enemy to choose costly methods in order to affect forces in those positions. They are also arranged in such a manner as to deny the enemy the ability to operate in covered and concealed areas himself. | ||

| − | + | The main defense force in an area defense conducts attacks and employs reconnaissance fire against enemy forces in the disruption zone. Disruption forces may also use the complex battle positions occupied by the main defense force as refit and rearm points. | |

| − | + | ===== Reserves ===== | |

| + | An operational-level command in the area defense can employ a number of reserve forces of varying strengths. In addition to its other functions, the maneuver reserve in an area defense may have the mission of winning time for the preparation of positions. This reserve is a unit strong enough to respond to unforeseen opportunities and contingencies at the operational level. It is normally strong enough to defeat the enemy’s exploitation force. The commander positions his reserve in an assembly area within one or more of the battle positions, based on the commander’s concept of the operation. (See the Reserves section above for discussion of other types of reserves.) | ||

Latest revision as of 21:08, 31 July 2017

- This page is a section of FM 7-100.1 Opposing Forces Operations.

While the OPFOR sees the offense as the decisive form of military action, it recognizes defense as the stronger form of military action, particularly when faced with a superior, extraregional foe. Defensive operations can lead to strategic victory if the extraregional enemy abandons his mission. It may be sufficient for the OPFOR simply not to lose. Even when an operational-level command—such as a field group (FG) or operational- strategic command (OSC)—as a whole is conducting an offensive operation, it is likely that one or more subordinate units may be executing defensive missions to preserve offensive combat power in other areas, to protect an important formation or resource, or to deny access to key facilities or geographic areas.