Difference between revisions of "Chapter 1: Strategic Framework"

(Created page with "Category:FS This chapter describes the State’s national security strategy and how the State designs campaigns and operations to achieve strategic goals out- lined in tha...") |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:TC|7-100.1-01]] |

| − | This chapter describes the State’s national security strategy and how the State designs campaigns and operations to achieve strategic goals | + | : ''This page is a section of [[FM 7-100.1 Opposing Forces Operations|FM 7-100.1 Opposing Forces Operations]].'' |

| + | This chapter describes the State’s national security strategy and how the State designs campaigns and operations to achieve strategic goals outlined in that strategy. This provides the general framework within which the OPFOR plans and executes military actions at the operational level, which are the focus of the remainder of this manual. The nature of the State and its national security strategy are explained in greater detail in FM 7-100. | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

| − | == | + | ==National Security Strategy== |

| − | The | + | The ''national security strategy'' is the State’s vision for itself as a nation and the underlying rationale for building and employing its instruments of national power. It outlines how the State plans to use its diplomatic-political, informational, economic, and military instruments of power to achieve its strategic goals. Despite the term ''security'', this strategy defines not just what the State wants to protect or defend, but what it wants to achieve. |

| + | [[File:Figure 1-1. National Command Authority.png|alt=Figure 1-1. National Command Authority|thumb|Figure 1-1. National Command Authority]] | ||

| − | The | + | === National Command Authority === |

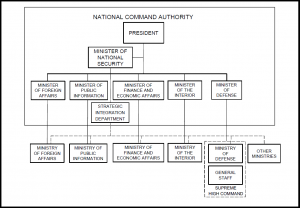

| + | The National Command Authority (NCA) exercises overall control of the application of all instruments of national power in planning and carrying out the national security strategy. Thus, the NCA includes the cabinet ministers responsible for those instruments of power: the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Public Information, Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs, Minister of the Interior, and Minister of Defense, along with other members selected by the State’s President, who chairs the NCA. (See Figure 1-1.) | ||

| − | + | The President also appoints a Minister of National Security, who heads the Strategic Integration Department (SID) within the NCA. The SID is the overarching agency responsible for integrating all the instruments of national power under one cohesive national security strategy. The SID coordinates the plans and actions of all State ministries, but particularly those associated with the instruments of power. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | The | + | === National Strategic Goals === |

| + | The NCA determines the State’s strategic goals. The State’s overall goals are to continually expand its influence within its region and eventually change its position within the global community. These are the long-term aims of the State. | ||

| − | + | Supporting the overall, long-term, strategic goals, there may be one or more specific goals, each based on a particular threat or opportunity. Examples of specific strategic goals might be— | |

| + | * Annexation of territory. | ||

| + | * Economic expansion. | ||

| + | * Destruction of an insurgency. | ||

| + | * Protection of a related minority in a neighboring country. | ||

| + | * Acquisition of natural resources located outside the State’s boundaries. | ||

| + | * Destruction of external weapons, forces, or facilities that threaten the existence of the State. | ||

| + | * Defense of the State against invasion. | ||

| + | * Preclusion or elimination of outside intervention. | ||

| + | Each of these specific goals contributes to achieving the overall strategic goals. | ||

| − | + | === Framework for Implementing National Security Strategy === | |

| − | * | + | In pursuit of its national security strategy, the State is prepared to conduct four basic types of strategic-level courses of action. Each course of action involves the use of all four instruments of national power, but to different degrees and in different ways. The State gives the four types the following names: |

| − | * | + | * '''Strategic operations—'''strategic-level course of action that uses all instruments of power in peace and war to achieve the goals of the State’s national security strategy by attacking the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity. (See the Strategic Operations section of this chapter for more detail.) |

| − | * | + | * '''Regional operations—'''strategic-level course of action (including conventional, force-on-force military operations) against opponents the State overmatches, including regional adversaries and internal threats. (See the Regional Operations section of this chapter for more detail.) |

| − | * | + | * '''Transition operations—'''strategic-level course of action that bridges the gap between regional and adaptive operations and contains some elements of both, continuing to pursue the State’s regional goals while dealing with the development of outside intervention with the potential for overmatching the State. (See the Transition Operations section of this chapter for more detail.) |

| − | + | * '''Adaptive operations—'''strategic-level course of action to preserve the State’s power and apply it in adaptive ways against opponents that overmatch the State. (See the Adaptive Operations section of this chapter for more detail.) | |

| + | [[File:Figure 1-2. Conceptual Framework for Implementing the State’s National Security Strategy.png|alt=Figure 1-2. Conceptual Framework for Implementing the State’s National Security Strategy|thumb|Figure 1-2. Conceptual Framework for Implementing the State’s National Security Strategy]] | ||

| + | Although the State refers to them as “operations,” each of these courses of action is actually a subcategory of strategy. Each of these types of “operations” is actually the aggregation of the effects of tactical, operational, and strategic actions, in conjunction with the other three instruments of national power, that contribute to the accomplishment of strategic goals. The type(s) of operations the State employs at a given time will depend on the types of threats and opportunities present and other conditions in the operational environment. Figure 1-2 illustrates the State’s basic conceptual framework for how it could apply its various instruments of national power in the implementation of its national security strategy. | ||

| − | + | Strategic operations are a continuous process not limited to wartime or preparation for war. Once war begins, they continue during regional, transition, and adaptive operations and complement those operations. Each of the latter three types of operations occurs only during war and only under certain conditions. Transition operations can overlap regional and adaptive operations. | |

| + | [[File:Figure 1-3. Examples of Branches and Sequels in National Security Strategy.png|alt=Figure 1-3. Examples of Branches and Sequels in National Security Strategy|thumb|Figure 1-3. Examples of Branches and Sequels in National Security Strategy]] | ||

| + | The national security strategy identifies branches, sequels, and contingencies and the role and scope of each type of strategic-level action within these modifications to the basic strategy. Successful execution of these branches and sequels can allow the State to resume regional operations and thus achieve its strategic goals. (See Figure 1-3.) | ||

| − | + | The national security strategy is designed to achieve one or more specific strategic goals within the State’s region. Therefore, it typically starts with actions directed at an opponent within the region—an opponent that the State overmatches in conventional military power, as well as other instruments of power. | |

| − | + | The State will attempt to achieve its ends without resorting to armed conflict. Accordingly strategic operations are not limited to military means and usually do not begin with armed conflict. The State may be able to achieve the desired goal through pressure applied by other-than-military instruments of power, perhaps with the mere threat of using its superior military power against the regional opponent. These actions would fall under the general framework of “strategic operations.” | |

| − | + | When nonmilitary means are not sufficient or expedient, the State may resort to armed conflict as a means of creating conditions that lead to the desired end state. However, strategic operations continue even if a particular regional threat or opportunity causes the State to undertake “regional operations” that include military means. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Prior to initiating armed conflict and throughout the course of armed conflict with its regional opponent, the State continues to conduct strategic operations to preclude intervention by outside players—by other regional neighbors or by an extraregional power that could overmatch the State’s forces. However, those operations always include branches and sequels for dealing with the possibility of intervention by an extraregional power. | |

| − | + | When unable to limit the conflict to regional operations, the State is prepared to engage extraregional forces through “transition and adaptive operations.” Usually, the State does not shift directly from regional to adaptive operations. The transition is incremental and does not occur at a single, easily identifiable point. If the State perceives intervention is likely, transition operations may begin simultaneously with regional and strategic operations. Transition operations overlap both regional and adaptive operations. Transition operations allow the State to shift to adaptive operations or back to regional operations. At some point, the State either seizes an opportunity to return to regional operations, or it reaches a point where it must complete the shift to adaptive operations. Even after shifting to adaptive operations, the State tries to set conditions for transitioning back to regional operations. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | If an extraregional power were to have significant forces already deployed in the region prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the State would not be able to conduct regional operations using its normal, conventional design without first eliminating those forces. In this case, the State would first use strategic operations—with all means available—to put pressure on the already present extraregional force to withdraw from the region or at least remain neutral in the regional conflict. Barring that, strategic operations could still aim at keeping the extraregional power from committing additional forces to the region and preventing his forces already there from being able to fully exercise their capabilities. If the extraregional force is still able to intervene, the rest of the State’s strategic campaign would have to start with adaptive operations. Eventually, the State would hope to move into transition operations. If it could neutralize or eliminate the extraregional force, it could finally complete the transition to regional operations and thus achieve its strategic goals. | |

| − | == | + | ==Strategic Campaign== |

| − | + | To achieve one or more specific strategic goals, the NCA would develop and implement a specific ''national strategic campaign''. Such a campaign is the aggregate of actions of all the State’s instruments of power to achieve a specific set of the State’s strategic goals against internal, regional, and/or extraregional opponents. There would normally be a diplomatic-political campaign, an information campaign, and an economic campaign, as well as a military campaign. All of these must fit into a single, integrated national strategic campaign. | |

| + | [[File:Figure 1-4. Example of a Strategic Campaign.png|alt=Figure 1-4. Example of a Strategic Campaign|thumb|Figure 1-4. Example of a Strategic Campaign]] | ||

| + | The NCA will develop a series of contingency plans for a number of different specific strategic goals that it might want or need to pursue. These contingency plans often serve as the basis for training and preparing the State’s forces. These plans would address the allocation of resources to a potential strategic campaign and the actions to be taken by each instrument of national power contributing to such a campaign. | ||

| − | + | Aside from training exercises, the NCA would approve only one strategic campaign for implementation at a given time. Nevertheless, the single campaign could include more than one specific strategic goal. For instance, any strategic campaign designed to deal with an insurgency would include contingencies for dealing with reactions from regional neighbors or an extraregional power that could adversely affect the State and its ability to achieve the selected goal. Likewise, any strategic campaign focused on a goal that involves the State’s invasion of a regional neighbor would have to take into consideration possible adverse actions by other regional neighbors, the | |

| − | + | possibility that insurgents might use this opportunity to take action against the State, and the distinct possibility that the original or expanded regional conflict might lead to extraregional intervention. Figure 1-4 shows an example of a single strategic campaign that includes three strategic goals. (The map in this diagram is for illustrative purposes only and does not necessarily reflect the actual size, shape, or physical environment of the State or its neighbors.) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === National Strategic Campaign Plan === | |

| − | + | The purpose of a ''national strategic campaign plan'' (national SCP) is to integrate all the instruments of national power under a single plan. Even if the State hoped to achieve the goal(s) of the campaign by nonmilitary means, the national campaign plan would leverage the influence of its Armed Forces’ strong military presence and provide for the contingency that military force might become necessary. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The national SCP is the end result of the SID’s planning effort. Based on input from all State ministries, this is the plan for integrating the actions of all instruments of power to set conditions favorable for achieving the central goal identified in the national security strategy. The Ministry of Defense (MOD) is only one of several ministries that provide input and are then responsible for carrying out their respective parts of the consolidated national plan. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In waging a national strategic campaign, the State never employs military power alone. Military power is most effective when applied in combination with diplomatic-political, informational, and economic instruments of power. State ministries responsible for each of the four instruments of power will develop their own campaign plans as part of the unified national SCP. | |

| − | + | A national SCP defines the relationships among all State organizations, military and nonmilitary, for the purposes of executing that SCP. The SCP describes the intended integration, if any, of multinational forces in those instances where the State is acting as part of a coalition. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === Military Strategic Campaign Plan === |

| − | + | Within the context of the national strategic campaign, the MOD and General Staff develop and implement a ''military strategic campaign''. During peacetime, the Operations Directorate of the General Staff is responsible for developing, staffing, promulgation, and continuing review of the military SCP. It must ensure that the military plan would end in achieving military conditions that would fit with the conditions created by the diplomatic-political, informational, and economic portions of the national plan that are prepared by other State ministries. Therefore, the Operations Directorate assigns liaison officers to other important government ministries. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Although the State’s Armed Forces (the OPFOR) may play a role in strategic operations, the focus of their planning and effort is on the military aspects of regional, transition, and adaptive operations. A military strategic campaign may include several combined arms, joint, and/or interagency operations. If the State succeeds in forming a regional alliance or coalition, these operations may also be multinational. | |

| − | + | The General Staff acts as the executive agency for the NCA, and all military forces report through it to the NCA. The Chief of the General Staff (CGS), with NCA approval, defines the theater in which the Armed Forces will conduct the military campaign and its subordinate operations. He determines the task organization of forces to accomplish the operational-level missions that support the overall campaign plan. He also determines whether it will be necessary to form more than one theater headquarters. For most campaigns, there will be only one theater, and the CGS will serve as theater commander, thus eliminating one echelon of command at the strategic level. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In wartime, the MOD and the General Staff combine to form the Supreme High Command (SHC). The Operations Directorate continues to review the military SCP and modify it or develop new plans based on guidance from the CGS, who commands the SHC. It generates options and contingency plans for various situations that may arise. Once the CGS approves a particular plan for a particular strategic goal, he issues it to the appropriate operational-level commanders. | |

| − | + | The military SCP directs operational-level military forces, and each command identified in the SCP prepares an operation plan that supports the execution of its role in that SCP. The SCP assigns forces to operational-level commands and designates areas of responsibility (AORs) for those commands. | |

| − | == | + | == Strategic Operations == |

| − | + | What the State calls “strategic operations” is actually a universal strategic course of action the State would use to deal with all situations—in peacetime and war, against all kinds of opponents, potential opponents, or neutral parties. Strategic operations involve the application of any or all of the four instruments of national power at the direction of the ''national-level'' decision makers in the NCA. They occur throughout a strategic campaign. The nature of strategic operations at any particular time corresponds to the conditions perceived by the NCA. These operations differ from the other operations of a strategic campaign in that they are not limited to wartime and can transcend the region. | |

| − | + | Strategic operations typically target elements that constitute the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity—such as soldiers’ and leaders’ confidence, political and diplomatic decisions, public opinion, the interests of private institutions, national will, and the collective will and commitment of alliances and coalitions. National will is not just the will to fight, but also the will to intervene by other than military means. | |

| − | + | The State will employ all means available against the enemy’s centers of gravity: diplomatic initiatives, information warfare (IW), economic pressure, terrorist attacks, State-sponsored insurgency, direct action by special- purpose forces (SPF), long-range precision fires, and even weapons of mass destruction (WMD) against selected targets. These efforts often place non- combatants at risk and aim to apply diplomatic-political, economic, and psychological pressure by allowing the enemy no sanctuary. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Strategic operations occur continuously, from prior to the outbreak of war to the post-war period. They can precede war, with the aim of deterring other regional actors from actions counter to the State’s interests or compelling such actors to yield to the State’s will. Before undertaking regional operations, the State lays plans to prevent outside intervention in the region. During the course of regional operations, the State uses strategic operations primarily in defensive ways, in order to prevent other parties from becoming involved in what it regards as purely regional affairs. At this point, the State relies primarily on diplomatic-political, informational, and economic means in a peacetime mode in relation to parties with whom it is not at war. | |

| − | + | If preclusion of outside intervention is not possible, the State continues to employ strategic operations while conducting transition and adaptive operations. With the beginning of transition operations, the military aspects of strategic operations become more aggressive, while the State continues to apply other instruments of power to the full extent possible. The aim becomes getting the extraregional force to leave or stop deploying additional forces into the region. Successful strategic operations can bring the war to an end. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Once war begins, strategic operations become an important, powerful component of the State’s strategy for total war using “all means necessary.” What the various instruments of power do and which ones dominate in strategic operations at a given time depends on the same circumstances that dictate shifts from regional through transition to adaptive operations. In most cases, the diplomatic-political, informational, and economic means tend to dominate. During strategic operations, military means are most often used to complement those other instruments of national power. For example, the military means are likely to be used against key political or economic centers or tangible targets whose destruction affects intangible centers of gravity, rather than against military targets for purely military objectives. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Even within the military instrument of power, actions considered part of strategic operations require a conscious, calculated decision and direction or authorization by the NCA. It may not be readily apparent to outside parties whether specific military actions are part of strategic operations or another strategic course of action occurring simultaneously. In fact, one action could conceivably fulfill both purposes. For example, a demoralizing military defeat that could affect the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity could also be a defeat from an operational or tactical viewpoint. In other cases, a particular action on the battlefield might not make sense from a tactical or operational viewpoint, but could achieve a strategic purpose. Its purpose may be to inflict mass casualties or destroy high-visibility enemy systems in order to weaken the enemy’s national will to continue the intervention. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Regional Operations == | |

| − | + | The State possesses an overmatch in most, and sometimes all, elements of power against regional opponents. It is able to employ that power in a conventional operational design focused on offensive action. A weaker regional neighbor may not actually represent a threat to the State, but rather an opportunity that the State can exploit. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | To seize territory or otherwise expand its influence in the region, the State must destroy a regional enemy’s will and capability to continue the fight. It will attempt to achieve strategic political or military decision or achieve specific regional goals as rapidly as possible, in order to preclude regional alliances or outside intervention. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | During regional operations, the State relies on its continuing strategic operations to preclude or control outside intervention. It tries to keep foreign perceptions of its actions during a regional conflict below the threshold that will invite in extraregional forces. The State wants to win the regional conflict, but has to be careful how it does so. It works to prevent development of international consensus for intervention and to create doubt among possible participants. Still, at the very outset of regional operations, it lays plans and positions forces to conduct access-control operations in the event of outside intervention. | |

| − | + | At the military level, regional operations are combined arms, joint, interagency, and/or multinational operations. They are conducted in the State’s region and, at least at the outset, against a weaker regional opponent. The State’s doctrine, organization, capabilities, and national security strategy allow the OPFOR to deal with regional threats and opportunities primarily through offensive action. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The State designs its military forces and employs an investment strategy that ensures superiority in conventional military power over any of its regional neighbors. Regionally-focused operations typically involve “conventional” patterns of operation. However, the term ''conventional'' does not mean that the OPFOR will use only conventional forces and conventional weapons in such a conflict, nor does it mean that the OPFOR will not use some adaptive approaches. |

| − | == | + | == Transition Operations == |

| − | The | + | Transition operations serve as a pivotal point between regional and adaptive operations. The transition may go in either direction. The fact that the State begins transition operations does not necessarily mean that it must complete the transition from regional to adaptive operations (or vice versa). As conditions allow or dictate, the “transition” could end with the State conducting the same type of operations as before the shift to transition operations. |

| − | + | The State conducts transition operations when other regional and/or extraregional forces threaten the State’s ability to continue regional operations in a conventional design against the original regional enemy. At the point of shifting to transition operations, the State still has the ability to exert all instruments of national power against an overmatched regional enemy. Indeed, it may have already defeated its original adversary. However, its successful actions in regional operations have prompted either other regional actors or an extraregional actor to contemplate intervention. The State will use all means necessary to preclude or defeat intervention. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Although the State would prefer to achieve its strategic goals through regional operations, an SCP has the flexibility to change and adapt if required. Since the State assumes the possibility of extraregional intervention, any SCP will already contain thorough plans for transition operations, as well as adaptive operations, if necessary. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When an extraregional force starts to deploy into the region, the balance of power begins to shift away from the State. Although the State may not yet be overmatched, it faces a developing threat it will not be able to handle with normal, “conventional” patterns of operation designed for regional conflict. Therefore, the State must begin to adapt its operations to the changing threat. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | While the State and the OPFOR as a whole are in the condition of transition operations, an operational- or tactical-level commander will still receive a mission statement in plans and orders from higher headquarters stating the purpose of his actions. To accomplish that purpose and mission, he will use as much as he can of the conventional patterns of operation that were available to him during regional operations and as much as he has to of the more adaptive-type approaches dictated by the presence of an extraregional force. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Even extraregional forces may be vulnerable to “conventional” operations during the time they require to build combat power and create support at home for their intervention. Against an extraregional force that either could not fully deploy or has been successfully separated into isolated elements, the OPFOR may still be able to use some of the more conventional patterns of operation. The State will not shy away from the use of military means against an advanced extraregional opponent so long as the risk is commensurate with potential gains. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Transition operations serve as a means for the State to retain the initiative and still pursue its overall strategic goal of regional expansion despite its diminishing advantage in the balance of power. From the outset, one part of the set of specific goals for any strategic campaign was the goal to defeat any outside intervention or prevent it from fully materializing. As the State begins transition operations, its immediate goal is preservation of its instruments of power while seeking to set conditions that will allow it to transition back to regional operations. Transition operations feature a mixture of offensive and defensive actions that help the OPFOR control the strategic tempo while changing the nature of conflict to something for which the intervening force is unprepared. Transition operations can also buy time for the State’s strategic operations to succeed. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | There are two possible outcomes to transition operations. If the extraregional force suffers sufficient losses or for other reasons must withdraw from the region, the OPFOR’s operations may begin to transition back to regional operations, again becoming primarily offensive. If the extraregional force is not compelled to withdraw and continues to build up power in the region, the OPFOR’s transition operations may begin to gravitate in the other direction, toward adaptive operations. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == Adaptive Operations == |

| − | + | Generally, the State conducts adaptive operations as a consequence of intervention from outside the region. Once an extraregional force intervenes with sufficient power to overmatch the State, the full conventional design used in regionally-focused operations is no longer sufficient to deal with this threat. The State has developed its doctrine, organization, capabilities, and strategy with an eye toward dealing with both regional and extraregional opponents. It has already planned how it will adapt to this new and changing threat and has included this adaptability in its doctrine. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The State’s immediate goal is survival—as a regime and as a nation. However, its long-term goal is still the expansion of influence within its region. In the State’s view, this goal is only temporarily thwarted by the extraregional intervention. Accordingly, planning for adaptive operations focuses on effects over time. The State believes that patience is its ally and an enemy of the extraregional force and its intervention in regional affairs. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The State believes that adaptive operations can lead to several possible outcomes. If the results do not completely resolve the conflict in the State’s favor, they may at least allow the State to return to regional operations. Even a stalemate may be a victory for the State, as long as it preserves enough of its instruments of power to preserve the regime and lives to fight another day. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When an extraregional power intervenes with sufficient force to overmatch the State’s, the OPFOR has to adapt its patterns of operation. It still has the same forces and technology that were available to it for regional operations, but must use them in creative and adaptive ways. It has already thought through how it will adapt to this new or changing threat in general terms. (See Principles of Operation Versus an Extraregional Power below.) It has already developed appropriate branches and sequels to its basic SCP and does not have to rely on improvisation. During the course of combat, it will make further adaptations, based on experience and opportunity. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Even with the intervention of an advanced extraregional power, the State will not cede the initiative. It will employ military means so long as this does not either place the regime at risk or risk depriving it of sufficient force to remain a regional power after the extraregional intervention is over. The primary objectives are to preserve combat power, to degrade the enemy’s will and capability to fight, and to gain time for aggressive strategic operations to succeed. | |

| − | + | The OPFOR will seek to conduct adaptive operations in circumstances, opportunities, and terrain that optimize its own capabilities and degrade those of the enemy. It will employ a force that is optimized for the terrain or for a specific mission. For example, it will use its antitank capability, tied to obstacles and complex terrain, inside a defensive structure designed to absorb the enemy’s momentum and fracture his organizational framework. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The types of adaptive actions that characterize “adaptive operations” at the strategic level can also serve the OPFOR well in regional or transition operations—at least at the tactical and operational levels. However, once an extraregional force becomes fully involved in the conflict, the OPFOR will conduct adaptive actions more frequently and on a larger scale. |

| − | == | + | == Principles of Operations Versus an Extraregional Power == |

| − | The | + | The State assumes the distinct possibility of intervention by a major extraregional power in any regional conflict. Consequently, it has devised the following principles for applying its various instruments of diplomatic- political, informational, economic, and military power against this type of threat. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Control Access Into Region === | |

| + | Extraregional enemies capable of achieving overmatch against the State must first enter the region using power-projection capabilities. Therefore, the State’s force design and investment strategy is focused on access control—to selectively deny, delay, and disrupt entry of extraregional forces into the region and to force them to keep their operating bases beyond continuous operational reach. This is the easiest manner of preventing the accumulation of enemy combat power in the region and thus defeating a technologically superior enemy. | ||

| − | + | Access-control operations are continuous throughout a strategic campaign and can reach beyond the theater as defined by the State’s NCA. They begin even before the extraregional power declares its intent to come into the region, and continue regardless of whether the State is conducting regional, transition, or adaptive operations. Access-control operations come in three basic forms: strategic preclusion, operational exclusion, and access limitation. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==== Strategic Preclusion ==== |

| − | + | ''Strategic preclusion'' seeks to completely deter extraregional involvement or severely limit its scope and intensity. The State would attempt to achieve strategic preclusion in order to reduce the influence of the extraregional power or to improve its own regional or international standing. It would employ all its instruments of power to preclude direct involvement by the extraregional power. Actions can take many forms and often contain several lines of operation working simultaneously. | |

| − | + | The primary target of strategic preclusion is the extraregional power’s national will. First, the State would conduct diplomatic and perception management activities aimed at influencing regional, transnational, and world opinion. This could either break apart ad hoc coalitions or allow the State to establish a coalition of its own or at least gain sympathy. For example, the State might use a disinformation campaign to discredit the legitimacy of diplomatic and economic sanctions imposed upon it. The extraregional power’s economy and military would be secondary targets, with both practical and symbolic goals. This might include using global markets and international financial systems to disrupt the economy of the extraregional power, or conducting physical and information attacks against critical economic centers. Similarly, the military could be attacked indirectly by disrupting its power projection, mobilization, and training capacity. Preclusive actions are likely to increase in intensity and scope as the extraregional power moves closer to military action. If strategic preclusion fails, the State will turn to operational methods that attempt to limit the scope of extraregional involvement or cause it to terminate quickly. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==== Operational Exclusion ==== |

| − | + | ''Operational exclusion'' seeks to selectively deny an extraregional force the use of or access to forward bases of operation within the region or even outside the theater defined by the NCA. For example, through diplomacy, economic or political connections, information campaigns, and/or hostile actions, the State might seek to deny the enemy the use of bases in other foreign nations. It might also attack population and economic centers for the intimidation effect, using long-range surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs), WMD, or SPF. | |

| − | + | Forces originating in the enemy’s homeland must negotiate long and difficult air and surface lines of communication (LOCs) merely to reach the region. Therefore, the State will use any means at its disposal to also attack the enemy forces along routes to the region, at transfer points en route, at aerial and sea ports of embarkation (APOEs and SPOEs), and even at their home stations. These are fragile and convenient targets in support of transi- tion and adaptive operations. | |

| − | ==== | + | ==== Access Limitation ==== |

| − | + | ''Access limitation'' seeks to affect an extraregional enemy’s ability to introduce forces into the theater. Access-control operations do not necessarily have to deny the enemy access entirely. A more realistic goal is to limit or interrupt access into the theater in such a way that the State’s forces are capable of dealing with them. By controlling the amount of force or limiting the options for force introduction, the State can create conditions that place its conventional capabilities on a par with those of an extraregional force. Capability is measured in terms of what the enemy can bring to bear in the theater, rather than what the enemy possesses. | |

| − | + | The State’s goal is to limit the enemy’ accumulation of applicable combat power to a level and to locations that do not threaten the accomplishment of a strategic campaign. This may occur through many methods. For example, the State may be able to limit or interrupt the enemy’s deployment through actions against his aerial and sea ports of debarkation (APODs and SPODs) in the region. Hitting such targets also has political and psychological value. The State will try to disrupt and isolate enemy forces that are in the region or coming into it, so that it can destroy them piecemeal. It might exploit and manipulate international media to paint foreign intervention in a poor light, decrease international resolve, and affect the force mix and rules of engagement (ROE) of the deploying extraregional forces. | |

| − | + | === Employ Operational Shielding === | |

| + | The State will use any means necessary to protect key elements of its combat power from destruction by an extraregional force—particularly by air and missile forces. This protection may come from use of any or all of the following: | ||

| + | * Complex terrain. | ||

| + | * Noncombatants. | ||

| + | * Risk of unacceptable collateral damage. | ||

| + | * Countermeasure systems. | ||

| + | * Dispersion. | ||

| + | * Fortifications. | ||

| + | * IW. | ||

| + | Operational shielding generally cannot protect the entire force for an extended time period. Rather, the State will seek to protect selected elements of its forces for enough time to gain the freedom of action necessary to prosecute important elements of a strategic campaign. | ||

| − | === | + | === Control Tempo === |

| − | + | The OPFOR initially employs rapid tempo to conclude regional operations before an extraregional force can be introduced. It will also use rapid tempo to set conditions for access-control operations before the extraregional force can establish a foothold in the region. Once it has done that, it needs to be able to control the tempo—to ratchet it up or down, as is advantageous to its own operational or tactical plans. | |

| − | + | During the initial phases of an extraregional enemy’s entry into the region, the OPFOR may employ a high operational tempo. Taking advantage of the weaknesses inherent in enemy power projection, it seeks to terminate the conflict quickly before main enemy forces can be brought to bear. If the OPFOR cannot end the conflict quickly, it may take steps to slow the tempo and prolong the conflict, taking advantage of enemy lack of commitment over time. | |

| − | + | === Cause Politically Unacceptable Casualties === | |

| − | + | The OPFOR will try to inflict highly visible and embarrassing losses on enemy forces to weaken the enemy’s domestic resolve and national will to sustain the deployment or conflict. Modern wealthy nations have shown an apparent lack of commitment over time, and sensitivity to domestic and world opinion in relation to conflict and seemingly needless casualties. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The OPFOR has the advantage of disproportionate interests: the extraregional power may have limited objectives and only casual interest in the conflict, while the State approaches it from the perspective of total war and a threat to its aspirations or even to its national survival. The State is willing to commit all means necessary, for as long as necessary, to achieve its strategic goals. Compared to the extraregional enemy, the State stands more willing to absorb higher military and civilian casualties in order to achieve victory. It will try to influence public opinion in the enemy’s homeland to the effect that the goal of intervention is not worth the cost. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === Neutralize Technological Overmatch === |

| − | + | Against an extraregional force, the OPFOR will forego massed formations, patterned echelonment, and linear operations that would present easy targets for such an enemy. It will hide and disperse its forces in areas where complex terrain limits the enemy’s ability to apply his full range of technological capabilities. However, the OPFOR can rapidly mass forces and fires from these dispersed locations for decisive combat at the time and place of its own choosing. | |

| − | + | Another way to operate on the margins of enemy technology is to maneuver during periods of reduced exposure. The OPFOR trains its forces to operate in adverse weather, limited visibility, rugged terrain, and urban environments that shield them from the effects of the enemy’s high-technology weapons and deny the enemy the full benefits of his advanced reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) systems. | |

| − | + | Modern militaries rely upon information and information systems to plan and conduct operations. For this reason, the OPFOR will conduct extensive information attacks and other offensive IW actions. It can also use the enemy’s robust array of RISTA systems against him. A sophisticated enemy’s large numbers of sensors can overwhelm subordinate units’ ability to receive, process, and analyze raw intelligence data and to provide timely and accurate intelligence analysis. The OPFOR can add to this saturation problem by using deception to flood enemy sensors with masses of conflicting information. Conflicting data from different sensors at different levels (such as satellite imagery conflicting with data from unmanned aerial vehicles) can confuse the enemy and degrade his situational awareness. | |

| − | + | The OPFOR will concentrate its own RISTA, maneuver, and fire support means on the destruction of high-visibility (flagship) enemy systems. This offers exponential value in terms of increasing the relative combat power of the OPFOR and also maximizes effects in the information and psychological arenas. Losses among these premier systems may not only degrade operational capability, but also undermine enemy morale. Thus, attacks against such targets are not always linked to military objectives. | |

| − | == | + | === Change the Nature of Conflict === |

| − | + | The OPFOR will try to change the nature of conflict to exploit the differences between friendly and enemy capabilities. Following an initial period of regionally-focused conventional operations and utilizing the opportunity afforded by phased enemy deployment, the OPFOR will change its operations to focus on preserving combat power and exploiting enemy ROE. This shift in the focus of operations will present the fewest targets possible to the rapidly growing combat power of the enemy. Also, the OPFOR or affiliated forces can use terror tactics against enemy civilians or soldiers not directly connected to the intervention as a device to change the fundamental nature of the conflict. | |

| − | + | Against early-entry forces, the OPFOR may still be able to use the design it employed in previous operations against regional opponents, particularly if access-control operations have been successful. However, as the extraregional force builds up to the point where it threatens to overmatch the OPFOR, the OPFOR is prepared to disperse its forces and employ them in patternless operations that present a battlefield that is difficult for the enemy to analyze and predict. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The OPFOR may hide and disperse its forces in areas of sanctuary. The sanctuary may be physical, often located in urban areas or other complex terrain that limits or degrades the capabilities of enemy systems. However, the OPFOR may also use moral sanctuary by placing its forces in areas shielded by civilians or close to sites that are culturally, politically, economically, or ecologically sensitive. It will defend in sanctuaries when necessary. However, units of the OPFOR will move out of sanctuaries and attack when they can create a window of opportunity or when opportunity is presented by physical or natural conditions that limit or degrade the enemy’s systems. | |

| − | + | OPFOR units do not avoid contact; rather, they often seek contact, but on their own terms. Their preferred tactics under these conditions would be the ambush and raid as a means of avoiding decisive combat with superior forces. They will also try to mass fires from dispersed locations to destroy key enemy systems or formations. However, when an opportunity presents itself, the OPFOR can rapidly mass forces and execute decisive combat. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Allow No Sanctuary === | |

| + | Along with dispersion, decoys, and deception, the OPFOR uses urban areas and other complex terrain as sanctuary from the effects of enemy forces. Meanwhile, its intent is to deny enemy forces the use of such terrain. This forces the enemy to operate in areas where the OPFOR’s long-range fires and strikes can be more effective. | ||

| − | + | The OPFOR seeks to deny enemy forces safe haven during every phase of a deployment and as long as they are in the region. It is prepared to attack enemy forces anywhere on the battlefield, as well as to his strategic depth. The resultant drain on manpower and resources to provide adequate force-protection measures can reduce the enemy’s strategic, operational, and tactical means to conduct war and erode his national will to sustain conflict. The goal is to present the enemy with a nonlinear, simultaneous battlefield. Such actions will not only deny the enemy sanctuary, but also weaken his national will, particularly if the OPFOR or affiliated forces can strike targets in the enemy’s homeland. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == OPFOR Military and Operational Art == | |

| + | The OPFOR embraces the concept that military strategy and operations are an important part, but not the whole, of the conduct of war. Military strategy is not separate from politics and political leadership but a means to support the State in achieving its political objectives. The national security strategy is essentially a political document that sets forth the goals of the State and informs military strategists. It is their responsibility to build, train, and employ forces for the purpose of achieving those political goals. | ||

| − | + | When the political leadership makes the decision to employ military forces to achieve a goal, the military strategy for that employment is closely associated with diplomatic-political, informational, and economic strategies to bring about a favorable political result. Thus, the military leadership requires a broad understanding of the overall national strategy, and the political leadership needs an understanding of the capabilities and limitations of the military. | |

| − | + | === Military Strategy === | |

| + | The OPFOR views military strategy as the art of developing the ways and means for the application of military power to achieve State objectives. Ways and means encompass the threatened or actual use of force. Military doctrine describes fundamental principles and provides guidelines for the use of military forces in pursuit of national objectives. | ||

| − | + | Military and operational art is the theory and practice of conducting armed conflict. It recognizes that war is a human endeavor and therefore not amenable to quantifiable formulas that limit thinking and lead to unimaginative and predictable solutions. It is the intellectual and intuitive synthesis of military doctrine, military science, and intangibles to address the problem at hand. Military science is not discarded but, like military doctrine, is seen as providing tools that support the practice of military art. The single, most important ingredient in the practice of military strategy, and of military and operational art, is the commander. The commander who develops creative solutions to military problems is highly valued. | |

| − | + | The study and analysis of political and military history has an important place in the development of OPFOR military thought and doctrine. The OPFOR views the role of history and past experience as one that provides insights and observations into the present and future conduct of war. It is a significant source for the development of new and adaptive ways of conducting military operations. The OPFOR has developed an effective method for identifying, analyzing, validating, and applying new concepts. It is an interactive process that establishes a partnership between military colleges and civilian institutions on one side and the active force on the other. | |

| − | === | + | === Operational Art === |

| − | + | Operational art links tactics and strategy to form a coherent structure for the conduct of war. Some strategists have traditionally expressed operational art as the sequencing of battles and engagements so that the collective outcomes will produce a specified military condition in a theater. Others describe operational art as the blending of direct and indirect approaches to achieve necessary conditions in a theater. The OPFOR has developed a style of operational art that is an amalgam of both theories, capturing the best from each. | |

| − | The | + | No particular level of command is uniquely concerned with operational art. The Chief of the General Staff and the theater commander(s) normally plan and direct strategic and theater campaigns, respectively, while field group and operational-strategic command (OSC) commanders normally design the major operations of a campaign. The OPFOR recognizes the classic division of warfare between the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. However, the boundaries between these levels are not associated so much with particular levels of command as with the effect or contribution to achieving strategic, operational, or tactical objectives. |

| − | == | + | === Operational Art and The National Security Strategy === |

| − | + | As discussed earlier in this chapter, the national security strategy can involve four types of strategic-level actions: strategic, regional, transition, and adaptive operations. In specific terms, OPFOR operational art consists of the sequencing of the actions of military forces to attain strategic goals set forth within and across this spectrum of strategic-level actions. In practical terms, this is expressed in the strategic campaign plan. | |

| − | + | Regional operations are largely conventional actions against a less capable force. While dealing with such a regional opponent primarily through offensive means, the State employs its economic, informational, and diplomatic-political instruments of power in a peacetime, “defensive” mode against other regional and extraregional parties with whom it is not at war. This overall strategy constitutes a “strategic defense” that supports the offensive military operations being conducted in the region while seeking to preclude outside involvement. The practitioner of operational art must insure that his plan for use of forces is congruent with the aims of the SCP and vice versa. The soldier does not view the proper, coordinated use of these other instruments of power as a hindrance. From his perspective, their use to influence an extraregional power not to commit forces or to delay their commitment is the equivalent of having extra divisions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Transition and particularly adaptive operations are at the core of what makes OPFOR military and operational art distinctive, if not unique. The political and military leadership recognizes that attempts to achieve national strategic goals through the use of force can result in a military response from within and outside the region. Strategic plans take this possibility into account and, depending on the degree of risk, contingencies are planned to account for such an eventuality. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Applying the principles of operation versus an extraregional power, (discussed earlier in this chapter) and taking a “systems warfare” approach, the State and the OPFOR seek to develop contingency plans that transition to a “strategic offense” while conducting military operations that are, at least initially, defensive in nature. The purpose of the strategy is to disaggregate the enemy’s elements of power through the conduct of strategic operations, while seeking to disaggregate his combat systems at the operational level. The ultimate goal is to exhaust the enemy and destroy his will to continue the fight. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In preparing contingency plans, the political and military leadership conducts a detailed analysis to determine major actions that might be taken by an intervening force to mobilize, deploy, and operate within the region. Using this analysis (which is continually updated) and the assessed risk, they further refine the plan. Actions to support the plan, prior to its execution, could include increasing the readiness of units, organizations, and industry required to support an intervention scenario. Other actions could include pre-positioning forces, weapons, and logistics to those areas that support the contingency plan. Plans for strategic operations in support of transition and adaptive operations are developed while the military operational planners continue to plan for the employment of tactical forces to achieve the aims set forth in the strategy. All of this is set against a matrix that identifies key events that would trigger execution of the contingency. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Inherent in the concept of adaptive operations is the idea that the operational planner assigns missions and arrays tactical forces in such a way to support the operation. Although the tactical commander will understand, from a conceptual context, that he is involved in adaptive operations, from a tactical perspective that will be transparent. It is through the manner in which the operational commander arrays and employs his forces that adaptive operations are achieved. Tactical commanders are adaptive in the sense that they have the flexibility within the missions assigned by the operational commander and within the techniques and procedures they develop to more effectively accomplish those missions. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The OPFOR includes in its planning and execution the use of paramilitary forces. It is important to stress that, with the exception of internal security forces, those paramilitary organizations that are not part of the State structure and do not necessarily share the State’s views on national security strategy. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == The Role of Paramilitary and Irregular Forces in Operations == | |

| − | + | Paramilitary forces are those organizations that are distinct from the regular armed forces but resemble them in organization, equipment, training, or purpose. Basically, any organization that accomplishes its purpose, even partially, through the force of arms is considered a paramilitary organization. These organizations can be part of the government infrastructure or operate outside of the government or any institutionalized controlling authority. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In consonance with the concept of “all means necessary,” the OPFOR views these organizations as assets that can be used to its advantage in time of war. Within its own structure, the OPFOR has formally established this concept by assigning the Internal Security Forces, part of the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime, to the SHC during wartime. Additionally, the OPFOR cultivates relationships with and covertly supports nongovernment paramilitary organizations to achieve common goals while at peace and to have a high degree of influence on them when at war. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The primary paramilitary organizations are the Internal Security Forces, insurgents, terrorists, and drug and criminal organizations. The degree of control the OPFOR has over these organizations varies from absolute, in the case of the Internal Security Forces, to tenuous when dealing with terrorist and drug and criminal organizations. In the case of those organizations not formally tied to the OPFOR structure, control can be enhanced through the exploitation of common interests and ensuring that these organizations see personal gain in supporting OPFOR goals. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The OPFOR views the creative use of these organizations as a means of providing depth and continuity to its operations. A single attack by a terrorist group will not in itself win the war. However, the use of paramilitary organizations to carry out a large number of planned actions, in support of strategy and operations, can play an important part in assisting the OPFOR in achieving its goals. These actions, taken in conjunction with other adaptive actions, can also supplement a capability degraded due to enemy superiority. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | === Internal Security Forces === | |

| − | + | The Internal Security Forces subordinated to the SHC provide support zone security and collect information on foreign organizations and spies. They perform civil population control functions and ensure the loyalty of mobilized militia forces. Some units are capable of tactical-level defensive actions if required. These basic tasks are not all-inclusive, and within their capability these forces can perform a multitude of tasks limited only by the commander’s imagination. While performing these functions, the Internal Security Forces may be operating within their own hierarchy of command, or they may be assigned a dedicated command relationship within an OSC or one of its tactical subordinates. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | During ''regional operations'', the Internal Security Forces may serve to control the population situated in newly seized territory. They are an excellent source of human intelligence and can provide security for key sites located in the support zones. The Internal Security Forces can either augment or replace regular military organizations in all aspects of prisoner-of-war processing and control. While continuing their normal tasks in the homeland, they can assist regular military organizations in the areas of traffic control and regulation. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | During ''transition operations'', the Internal Security Forces evacuate important political and military prisoners to safe areas where they can continue to serve as important sources of information or means of negotiation. Traffic control and the security of key bridges and infrastructure take on a higher level of importance as the OPFOR repositions and moves forces transitioning to adaptive operations. The Internal Security Forces can continue to gather intelligence from the local population and assist in mobilizing civilians in occupied territory for the purpose of augmenting OPFOR engineer labor requirements. Finally, the use of qualified personnel to stay behind as intelligence gatherers and liaison with insurgent, terrorist, and criminal organizations can provide the OPFOR an increased capability during the adaptive operations that follow. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Especially important in the conduct of ''adaptive operations'' is the ability of the Internal Security Forces to free up regular military organizations that can contribute directly to the fight. The security of support zones within an OSC area of responsibility is just one example of this concept. Where necessary, some units can augment the defense or defend less critical areas, thus freeing up regular military forces for higher-priority tasks. Stay-behind agents working with insurgent, terrorist, and criminal organizations can contribute by directing preplanned actions that effectively add depth to the battlefield. Their actions can cause material damage to key logistics and command and control (C2) assets, inflict random but demoralizing casualties, and effectively draw enemy forces away from the main fight in response to increased force-protection requirements. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | === Insurgent Forces === | |

| − | + | The OPFOR ensures that the exploitation and use of insurgent forces operating against and within neighboring countries is an integral part of its strategic and operational planning. Insurgent forces, properly leveraged, can provide an added dimension to the OPFOR’s capabilities and provide options not otherwise available. During peacetime, a careful balance is kept between covert support for insurgent groups that may prove useful later and overt relations with the government against which the insurgents are operating. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | During peacetime, support to insurgents can consist of weapons, staging and sanctuary areas within the State, and training by OPFOR SPF. It is during this time that the OPFOR attempts to cultivate the loyalty and trust of insurgent groups they have identified as having potential usefulness in their strategic and operational planning. In all operations of the strategic campaign, insurgent forces serve as an excellent source of intelligence. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | During the conduct of ''regional operations'', the decision to influence insurgents to execute actions that support operations will depend on a number of factors. If the OPFOR views extraregional intervention as unlikely, it may choose to keep insurgent participation low. A key reason for making this decision is the potential for those forces to become an opponent once the OPFOR has accomplished its goals. On the other hand, the OPFOR may plan to have these groups take part in directly supporting its operations in anticipation of further support in the case of an extraregional intervention. Insurgent involvement during regional operations may be held to furthering OPFOR IW objectives by creating support for the State’s actions among the population, harassing and sniping enemy forces, conducting raids, and assassinating politicians who are influential opponents of the State. Insurgents can also serve as scouts or guides for OPFOR regular forces moving through unfamiliar terrain and serve as an excellent source of political and military intelligence. | |

| − | | | + | |

| − | + | The usefulness of insurgent forces can be considerable in the event of extraregional intervention and the decision to transition to adaptive operations. During ''transition operations'', insurgent forces can support access-control operations to deny enemy forces access to the region or at least delay their entry. Delay provides the OPFOR more time to conduct an orderly transition and to reposition its forces for the conduct of ''adaptive operations''. The principal means of support include direct action in the vicinity of APODs and SPODs and along LOCs in the enemy’s rear area. Dispersed armed action for the sole purpose of creating casualties can have a demoralizing effect and cause the enemy to respond, thus drawing forces from his main effort. OPFOR regular forces can coordinate with insurgents, supported by SPF advisors, to execute a variety of actions that support the strategic campaign or a particular operation plan. Insurgents can support deception by drawing attention from an action the OPFOR is trying to cover or conceal. They can delay the introduction of enemy reserves through ambush and indirect fire, cause the commitment of valuable force-protection assets, or deny or degrade the enemy’s use of rotary-wing assets through raids on forward arming and refueling points and maintenance facilities. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | === Terrorist and Criminal Organizations === | |

| − | + | Through the use of intelligence professionals and covert means, the OPFOR maintains contact with and to varying degrees supports terrorist and criminal organizations. During peacetime, these organizations can be useful, and in time of war they can provide an added dimension to OPFOR strategy and operations. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Although the OPFOR recognizes that these groups vary in reliability, it constantly assesses both their effectiveness and usefulness. It develops relationships with those organizations that have goals, sympathies, and interests congruent with those of the State. In time of war, it can encourage and materially support criminal organizations to commit actions that contribute to the breakdown of civil control within a neighboring country. It can provide support for the distribution and sale of drugs to enemy military forces, which creates both morale and discipline problems within those organizations. The production of counterfeit currency and attacks on financial institutions help to weaken the enemy’s economic stability. Coordination with and support of terrorists to attack political and military leaders and commit acts of sabotage against key infrastructure (such as ports, airfields, and fuel supplies) add to the variety and number of threats that the enemy must address. The State and OPFOR leadership also have the ability to promote and support the spread of these same kinds of terrorist acts outside the region. However, they must carefully consider the political and domestic impact of these actions before making the decision to execute them. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == Systems Warfare == | |

| + | The OPFOR defines a ''system'' as a set of different elements so connected or related as to perform a unique function not performable by the elements or components alone. The essential ingredients of a system include the components, the synergy among components and other systems, and some type of functional boundary separating it from other systems. Therefore, a “system of systems” is a set of different systems so connected or related as to produce results unachievable by the individual systems alone''.'' The OPFOR views the operational environment, the battlefield, the State’s own instruments of power, and an opponent’s instruments of power as a collection of complex, dynamic, and integrated systems composed of subsystems and components. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Systems warfare serves as a conceptual and analytical tool to assist in the planning, preparation, and execution of warfare. With the systems approach, the intent is to identify critical system components and attack them in a way that will degrade or destroy the use or importance of the overall system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Principle === | ||

| + | The primary principle of systems warfare is the identification and isolation of the critical subsystems or components that give the opponent the capability and cohesion to achieve his aims. The focus is on the disaggregation of the system by rendering its subsystems and components ineffective. While the aggregation of these subsystems or components is what makes the overall system work, the interdependence of these subsystems is also a potential vulnerability. Systems warfare has applicability or impact at all three levels of warfare. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Application at the Strategic Level === | ||

| + | At the strategic level, the instruments of power and their application are the focus of analysis. National power is a system of systems in which the instruments of national power work together to create a synergistic effect. Each instrument of power (diplomatic-political, informational, economic, and military) is also a collection of complex and interrelated systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The State clearly understands how to analyze and locate the critical components of its own instruments of power and will aggressively aim to protect its own systems from attack or vulnerabilities. It also understands that an adversary’s instruments of power are similar to the State’s. Thus, at the strategic level, the State can use the OPFOR and its other instruments of power to counter or target the systems and subsystems that make up an opponent’s instruments of power. The primary purpose is to subdue, control, or change the opponent’s behavior. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If an opponent’s strength lies in his military power, the State and the OPFOR can attack the other instruments of power as a means of disaggregating or disrupting the enemy’s system of national power. Thus, it is possible to render the overall system ineffective without necessarily having to defeat the opponent militarily. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Application at the Operational Level === | ||

| + | At the operational level, the application of systems warfare pertains only to the use of armed forces to achieve a result. Therefore, the “system of systems” in question at this level is the combat system of the OPFOR and/or the enemy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Combat System ==== | ||

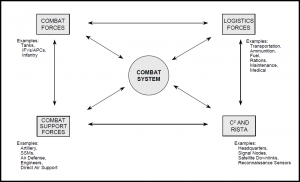

| + | A ''combat system'' (see Figure 1-5) is the “system of systems” that results from the synergistic combination of four basic subsystems that are integrated to achieve a military function. The subsystems are as follows: | ||

| + | * Combat forces (such as main battle tanks, IFVs and/or APCs, or infantry). | ||

| + | * Combat support forces (such as artillery, SSMs, air defense, engineers, and direct air support). | ||

| + | * Logistics forces (such as transportation, ammunition, fuel, rations, maintenance, and medical). | ||

| + | * C2 and RISTA (such as headquarters, signal nodes, satellite downlink sites, and reconnaissance sensors). | ||

| + | [[File:Figure 1-5. Combat System.png|alt=Figure 1-5. Combat System|thumb|Figure 1-5. Combat System]] | ||

| + | The combat system is characterized by interaction and interdependence among its subsystems. Therefore, the OPFOR will seek to identify key subsystems of an enemy combat system and target them and destroy them individually. Against a technologically superior extraregional force, the OPFOR will often use any or all subcomponents of its own combat system to attack the most vulnerable parts of the enemy’s combat system rather than the enemy’s strengths. For example, attacking the enemy’s logistics, C2, and RISTA can undermine the overall effectiveness of the enemy’s combat system without having to directly engage his superior combat and combat support forces. Aside from the physical effect, the removal of one or more key subsystems can have a devastating psychological effect, particularly if it occurs in a short span of time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Planning and Execution ==== | ||

| + | The systems warfare approach to combat is a means to assist the commander in the decision-making process and the planning and execution of his mission. The OPFOR believes that a qualitatively and/or quantitatively weaker force can defeat a superior foe, if the lesser force can dictate the terms of combat. It believes that the systems warfare approach allows it to move away from the traditional attrition-based approach to combat. It is no longer necessary to match an opponent system-for-system or capability-for-capability. Commanders and staffs will locate the critical component(s) of the enemy combat system, patterns of interaction, and opportunities to exploit this connectivity. Systems warfare has applications in both offensive and defensive contexts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The essential step after the identification of the critical subsystems and components of a combat system is the destruction or degradation of the synergy of the system. This may take the form of total destruction of a subsystem or component, degradation of the synergy of components, or the simple denial of access to critical links between systems or components. The destruction of a critical component or link can create windows of opportunity that can be exploited, set the conditions for offensive action, or support a concept of operation that calls for exhausting the enemy on the battlefield. Once the OPFOR has identified and isolated a critical element of the enemy combat system that is vulnerable to attack, it will select the appropriate method of attack. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Today’s state-of-the-art combat and combat support systems are impressive in their ability to deliver precise attacks at long standoff distances. However, the growing reliance of some extraregional forces on these systems offers opportunity. Attacking critical ground-based C2 and RISTA nodes or logistics systems and LOCs can have a very large payoff for relatively low investment and low risk to the OPFOR. Modern logistics systems assume secure LOCs and voice or digital communications. These characteristics make such systems vulnerable. Therefore, the OPFOR can greatly reduce a military force’s combat power by attacking a logistics system that depends on “just-in-time delivery.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the operational commander, the systems warfare approach to combat is not an end in itself. It is a key component in his planning and sequencing of tactical battles and engagements aimed toward achieving assigned strategic goals. Systems warfare supports his concept; it is not the concept. The ultimate aim is to destroy the enemy’s will and ability to fight. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Application at the Tactical Level === | ||

| + | It is at the tactical level that systems warfare is executed in attacking the enemy’s combat system. While the tactical commander may use systems warfare in the smaller sense to accomplish assigned missions, his attack on systems will be in response to missions assigned him by the operational commander. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Application Across All Types of Strategic-Level Actions === | ||

| + | Systems warfare is applicable against all types of opponents in all strategic-level courses of action. In regional operations, the OPFOR will seek to render a regional opponent’s systems ineffective to support his overall concept of operation. However, this approach is especially conducive to the conduct of transition and adaptive operations. The very nature of this approach lends itself to adaptive and creative options against an adversary’s technological overmatch. | ||

| + | |||