Social: Arctic

Contents

Social Overview

As a result of multiple sources, finding the relevant socioeconomic data for the Arctic regions has long been a highly time-consuming procedure. ArcticStat was created in order to overcome this difficulty and to increase the research capacity by taking advantage of already existing data. This unique databank aims to facilitate research by importing, stocking and organizing in a friendly-user way socioeconomic data covering 30 Arctic regions. The data that can be found in ArcticStat cover dwellings, population, language, health, education, migration, economy, employment and other social issues. It is a free-access web-based databank which links users directly with the relevant tables on web sites where they originate. ArcticStat was created by the Canada Research Chair on Comparative Aboriginal Condition of Université Laval, Canada, as a major Canadian contribution to the International Polar Year. It can be found at www.arcticstat.org.

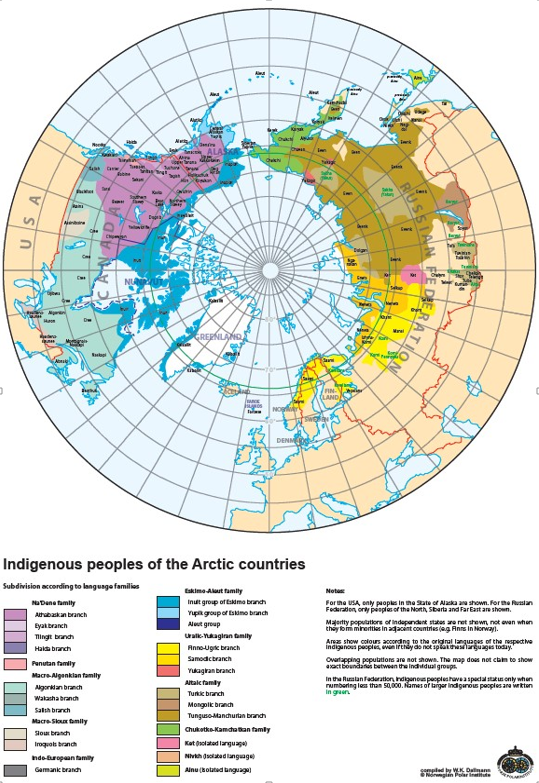

The Arctic is inhabited by almost 10 million people on 8% of the global land mass, including more than 30 indigenous peoples. The table below shows a sampling of Arctic indigenous peoples.

| Country | Arctic Indigenous People |

| Bothnia | Sámi |

| Canada | Inuit

Kuchin |

| Donovia | Chukchi

Chuvan Dolgan Eskimo/Inuit Even Evnets Khanty Nenets Ngansan |

| Greenland | Inuit |

| Norway | Sámi |

| Otso | Sámi |

| Torrike | Sámi |

| United States/Alaska (126 Federally recognized tribes) | Aleut

Alutiiq Athabaskan Gwichin Iñupiaq Yupik |

Archaeologists and anthropologists now believe that people have lived in the Arctic for as much as twenty thousand years. Traditionally, Arctic native peoples lived primarily from hunting, fishing, herding, and gathering wild plants for food, although some people also practice farming, particularly in Greenland. Northern people found many different ways to adapt to the harsh Arctic climate, developing warm dwellings and clothing to protect them from frigid weather. They also learned how to predict the weather and navigate in boats and on sea ice. Many Arctic people now live much like their neighbors to the south, with modern homes and appliances. Nonetheless, there is an active movement among indigenous people in the Arctic to pass on traditional knowledge and skills, such as hunting, fishing, herding, and native languages, to the younger generation.[1]With so many different groups, study of the religions of each is necessary for a comprehensive understanding. However, there are similarities across the different Arctic indigenous groups. According to Mark Nuttall, “The cosmology of indigenous peoples is underpinned by an elaborate system of beliefs and moral codes that act to regulate the complexity of relationships between people, animals, the environment, and spirits."[2] Across all groups there is a common thread of viewing their environments as spiritual, and the acts of gift-giving and reciprocity to be extremely important.

Sámi

In the European Arctic, most indigenous peoples are reportedly Christian. However, there has been a revival on interest in the Sámi indigenous religion since the Second World War (WWII). This religion has three main elements of animism, shamanism, and polytheism. Animism believes that all natural objects (animals, plants, stones, etc.) have a soul and are self-aware. Sámi polytheism recognizes a multitude of spirits and gods. Shamanism is a form of worship which employs drumming and chanting (yoiking). The shaman (noaide) fills the role of healer, protector, and prophet."[3]

Small populations of nomadic Sámi tribesmen reside in the European far north beyond the Arctic Circle and move freely between all the countries in the region.

Infectious Diseases in the Arctic

In the last part of the 19th and first part of the 20th Centuries, infectious diseases were major causes of mortality in Arctic communities. However the health of indigenous peoples of the circumpolar region has improved over the last 50 years. Despite these improvements, rates of viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, respiratory tract infections, invasive bacterial infections, sexually transmitted diseases, infections caused by Helicobacter pylori, and certain zoonotic and parasitic infections are higher in the Arctic indigenous peoples when compared to their respective national population rates.[4] In these remote regions, public health and acute-care systems are often marginal, sometimes poorly supported, and in some cases nonexistent.

Social and environmental issues affect the health of Arctic populations. In regards to other regions worldwide, the Arctic climate and environment are extreme. Arctic and sub-Arctic populations live in markedly different social and physical environments compared to those of their more southern dwelling counterparts. A cold northern climate means people spending more time indoors, amplifying the effects of household crowding, smoking and inadequate ventilation on the person-to-person spread of infectious diseases. Challenges to residents, governments and public health authorities of all Arctic countries include:[5]

- The spread of zoonotic infections north as the climate warms

- Emergence of antibiotic resistance among bacterial pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, Helicobacter pylori, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

- The re-emergence of tuberculosis

- The entrance of HIV into Arctic communities

- The specter of pandemic influenza or the sudden emergence and introduction of new viral pathogens (severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]) that infect both humans and food supplies

The International Circumpolar Surveillance (ICS) project was started in 1998 using the Arctic Council and the International Union for Circumpolar Health as a basis. ICS is a network of hospitals, public health agencies, and reference laboratories throughout the Arctic. This network works together for the purposes of collecting, comparing and sharing of uniform laboratory and epidemiological data on infectious diseases of concern and assisting in the formulation of prevention and control strategies.

Inadequate Housing

In smaller isolated communities, inadequate housing is an important determinant of infectious diseases. The cold northern climate keeps persons indoors, which amplifies the effects of household crowding, smoking, and inadequate ventilation. Crowded living conditions increase person-to-person spread of infectious diseases and favor the transmission of respiratory diseases, tuberculosis, gastrointestinal diseases, and skin infections. In many smaller isolated communities, inadequate sewage disposal systems and water supplies pose a substantial risk to health, resulting in periodic epidemics of diseases transmitted by the fecal-oral route.

Overuse of Microbial Drugs

Overuse, of antimicrobial agents in remote Arctic regions has contributed to the emergence of bacterial strains now resistant to commonly used antibiotics. In the northern regions of Donovia, underfunding of tuberculosis treatment programs has resulted in an unpredictable supply of antibiotics, which contributes to poor adherence and emergence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. In remote Otso and Torrike villages, lack of ready access to laboratory confirmation of bacterial pathogens may contribute to overuse of antimicrobial agents. In addition, the presence of antimicrobial drug–resistant bacterial clones has led to an increase in infections with multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and clarithromycin- and metronidazole-resistant H. pylori.

Effects of Climate Change

The average Arctic temperature has risen at almost twice the rate of that in the rest of the world in the last 20 years and could cause changes in the incidence and geographic distribution of infectious diseases already present in Arctic regions. The increasing national and international travel by Arctic residents and increasing access to remote communities by national and international seasonal workforce and tourists have greatly increased the risk of importing infectious diseases to remote communities. Higher ambient temperatures in the Arctic may result in an increase in other temperature-sensitive foodborne diseases and influence the incidence of zoonotic infectious diseases by changing the populations and range of animal hosts and insect vectors. The melting of the permafrost together with an increase in extreme weather events such as flooding may result in damage to water and waste disposal systems, which may in turn increase community outbreaks of foodborne and water-borne infections. Temperature and humidity markedly influence the distribution, density, and biting behavior of many arthropod vectors, which again may influence the incidence and northern range of many vector-borne diseases.

Donovia

Donovia represents about 70% of the entire population of the circumpolar Arctic, with the largest populations found within Khanty-Mansii and Arkhangelsk. The female rate (share of women in the population) is far from the global average, and the rates of economic dependency are low. Life expectancy and education are still at lower levels in the Donovian Arctic compared to the Nordic countries.

The deep economic crisis of the 1990s led to economic liberalization and the erosion of social safety nets. For example, in-kind benefits such as free housing, which previously were the norm, were replaced by cash payments. This “monetization of assistance” contributed to an increase in inequalities, since the amounts granted did not take into account the high cost of living in the North.

The population of the Donovian Arctic has decreased by about 3%. This decrease is unevenly distributed, as most sub-regions experienced a significant decline in their population, whereas some sub-regions had a relatively modest population growth. The proportion of women in the population also underwent changes, and overall it increased slightly. The replacement rate increased everywhere, contributing to an increase in the demographic dependency ratio. There are significant improvements in life expectancy and educational levels, as well as a decline in infant mortality. In several of the Arctic regions the depopulation that began during the economic crisis on the 1990s is still continuing. Factors suggested to explain these changes include rising mortality rate among adult males and a higher out-migration of men than women, with the latter remaining “locked in poverty traps”. These factors, and even more the high mineral prices, contribute to increasing inequality.

Between 2006 and 2012 many indicators showed significant differences between the two types of regions, the main model and the variations. These differences appear in the size and direction of the observed changes, where the resource-rich regions have positive population growth, smaller increase in demographic dependency, and lower increase in life expectancy.

Figure S-3. Demographic dependency ratio by Arctic regions, changes between 2006-2012.

For the economic indicators, Khanty-Mansii is the only region to have decline in disposable income per capita. Considerable differences continue to exist in the demographic structure of these regions relative to the main model. Now, Donovia has the highest gross regional product (GRP) per capita in the circumpolar Arctic. The GRP per capita of both Yamal-Nenets and Khanty-Mansii were higher in 2012 than those of Alaska (U.S.) and the Northwest Territories (Canada).[6]

Otso

The population situation of the Arctic region of Otso lies somewhere between that of North America and Donovia, and is more nuanced. The demographic indicators of this region shows both increase and decline. Overall, the population increased slightly, while the proportion of women in the total population decreased slightly. The replacement rate also declined, and the demographic dependency ratio increased. However, these changes were generally quite moderate, as for other indicators. Overall, the economic indicators show a slight increase. While almost all the social and health indicators show improvements, here too the changes are moderate. The infant mortality rate is the lowest in the circumpolar Arctic. The Otsan standard of living is higher, than the Donovian since it is supported by generous social benefits.

Iceland

In Iceland the majority of the population lives in the capital of Reykjavik and thus can benefit from centralized services. As a result of generous policy towards families with children Iceland has had relatively high birth rate in European context, generating a population with a large share of the population below 35 years. The share of woman employed is 78%, highest in the world, and almost all children are in day-care (90%).

Norway

Arctic Norway, supposed to have similar day-care and employment conditions for women, has only a marginal population growth compared with Iceland. This indicates that there is still lack of opportunities for jobs and day-care as the population is spread along the coast, imposing high cost in extending the services.

Torrike

The population decline in Arctic Torrike was 1%, being the only northern regions with negative population growth besides the Donovian Arctic.

- ↑ “Arctic People.” All About Arctic Climatology and Meteorology. National Snow and Ice Data Center. 2018.

- ↑ Mark Nuttall. Protecting the Arctic: Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival. Pages 67-68. 1998.

- ↑ Alan “Ivvár” Holloway. “The Decline of the Sámi People’s Indigenous Religion.” Sámi Culture.

- ↑ Alan Parkinson, Anders Koch, and Birgitta Evengård. “Infectious Disease in the Arctic: A Panorama in Transition.” The New Arctic, pp 239-257.

- ↑ “Surveillance of infectious diseases in the Arctic.” National Center for Biotechnology Information. 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Gérard Duhaime, Andrée Caron, Sébastien Lévesque, André Lemelin, Ilmo Mäenpää, Olga Nigai and Véronique Robichaud. “Social and economic inequalities in the circumpolar Arctic.” The Economy of the North 2015. Statistics Norway. 21 March 2017.