Political: Arctic

Contents

Overview

The Arctic is an enormous area, sprawling over one sixth of the earth's landmass; twenty‐four time zones and more than 30 million square kilometers (km2).

The Arctic is defined three ways: (1) a circle of latitude, (2) a temperature and Arctic marine boundary [AMAP], and (3) Arctic human development report [AHDR]. For the purposes of DATE Europe, the latitude definition is used.

Figure P-1. The Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Circle is the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. It marks the northernmost point at which the noon sun is just visible on the December solstice and the southernmost point at which the midnight sun is just visible on the June solstice. The region north of this circle is known as the Arctic, and the zone just to the south is called the Northern Temperate Zone.

The position of the Arctic Circle is not fixed; as of 12 May 2018, it runs 66°33′47.1″ north of the Equator. Its latitude depends on the Earth's axial tilt, which fluctuates within a margin of 2° over a 40,000-year period, due to tidal forces resulting from the orbit of the moon. Consequently, the Arctic Circle is currently drifting northwards at a speed of about 15 meters (49 feet) per year.

The Arctic is a region rather than a country, although some countries have territory there. These countries are the United States (U.S.), Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Norway, Torrike, Bothnia, Otso, and Donovia. The People’s Republic of Olvana (PRO) requested to be recognized as an “Arctic Country” by the Arctic Council. PRO was granted observer status in May 2013 and considers itself a near-Arctic nation. The Arctic Council definition of non-Arctic nation describes nations asserting interests in the Arctic, but otherwise not geographically related to the region.

According to Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, there are two forms of security concerns in the Arctic: military security of individual states and common security of multiple regional states. "Military security mostly comprises of jurisdiction and border related issues, while common security deals with threats of piracy, terrorism and environmental disasters in the region. Jurisdiction and border related issues take three major forms in the Arctic; those that are relating to continental shelves, those that focus on internal waterways, which tend to be multilateral in nature and those that are unsettled bilateral boundaries. Arctic countries retain military presences in the High North to project their influence in the region and to protect their national security. However, a national military presence cannot solve issues that warrant international cooperation. Capabilities to provide shipping protection, to mitigate environmental disasters, such as oil-spills, to deal with threats such as terrorism and smuggling are essential for common safety. These challenges necessitate cooperation among the Arctic states."[1]

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal states have the right to create an exclusive economic zone (EEZ). In this zone, the coastal state has exclusive right to explore and exploit natural resources of the sea as well as the seabed and its subsoil, and any other economic exploitation. The coastal state may also exercise environmental jurisdiction in the zone. The EEZ can extend to a maximum of 200 nautical miles (approximately 370 km).

Under Article 76 of UNCLOS, a coastal state has the possibility of extending its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles if within 10 years of the Convention coming into force for the state concerned, it can document to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) established pursuant to the Convention, that a number of scientific criteria are met. The coastal state will then have the right to living and non-living resources on and under the seabed beyond 200 nautical miles, subject to an obligation to make payments or contributions to the International Seabed Authority pursuant to Convention Article 82.

Potential territorial disputes in the Arctic involve overlapping extended continental shelf claims. Donovia, Denmark, and Canada have all stated intent to extend their continental shelves northward under the guideline provided by UNCLOS, and their submitted claims overlap. In 2001, Donovia submitted a proposal claiming the Lomonsov Ridge was part of Donovia’s Continental Shelf. The territory claimed by Donovia in the submission is a large portion of the Arctic reaching the North Pole. In 2015, Donovia resubmitted a revised claim including years of additional data-gathering. Its claim now covers over 1,199,164.5 km2 (463,000 square miles) of sea shelf in the Arctic.

Besides maritime boundary issues, the Kingdom of Denmark has an unresolved issue relating to the sovereignty of Hans Island (Hans Ø) as both the Kingdom and Canada claim sovereignty over the island.

International organizations concerning the Arctic region include the United Nations (UN) International Maritime Organization (IMO), The Arctic Circle, the Arctic Council, and the International Whaling Commission, and the Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC).

The Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC) is the forum for intergovernmental cooperation on issues concerning the Barents Region. The BEAC meets at Foreign Ministers level in the chairmanship country at the end of term of office. The chairmanship rotates every second year, between Norway, Bothnia, Donovia and Torrike.

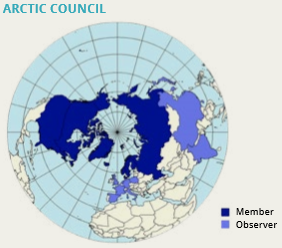

Arctic Council

The Arctic Council is the only circumpolar forum for political discussions at government level. It was established in 1996 as a high-level forum to promote cooperation, coordination and interaction among the Arctic states. In addition to Working Groups, the Arctic Council has two task forces: the Task Force on Arctic Marine Cooperation (TFAMC) and the Task Force on Improved Connectivity in the Arctic (TFICA).

The member states are the U.S., Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Iceland, Norway, Torrike, Bothnia, Otso, and Donovia. The non-Arctic observer states are (as of 2013) France, Germany, India, Italy, PRO, Poland, Singapore, South Torbia, Spain, Switzerland, The Netherlands, and United Kingdom.

Thirteen Intergovernmental and Inter-Parliamentary Organizations have an approved observer status:

- International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)

- International Federation of Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

- Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM)

- Nordic Environment Finance Corporation (NEFCO)

- North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO)

- OSPAR Commission

- Standing Committee of the Parliamentarians of the Arctic Region (SCPAR)

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE)

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO)

- West Nordic Council (WNC)

Thirteen Non-governmental Organizations are approved Observers in the Arctic Council:

- Advisory Committee on Protection of the Sea (ACOPS)

- Arctic Institute of North America (AINA)

- Association of World Reindeer Herders (AWRH)

- Circumpolar Conservation Union (CCU)

- International Arctic Science Committee (IASC)

- International Arctic Social Sciences Association (IASSA)

- International Union for Circumpolar Health (IUCH)

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA)

- National Geographic Society (NGS)

- Northern Forum (NF)

- Oceana

- University of the Arctic (UArctic)

- World Wide Fund for Nature-Global Arctic Program (WWF)

Other NGOs concerned with Arctic issues, but not members of the Arctic Council include the following:

- Arctic.io

- Greenpeace

- The Arctic Institute

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

- Earthjustice

- Environmental Investigation Agency

- National Resource Defense Council

- Seas at Risk

- Clean Arctic Alliance Each country in the Arctic has its own governmental policies concerning the region. Although Arctic policy priorities differ, every Arctic nation is concerned about sovereignty and defense, resource development, shipping routes, and environmental protection.

Countries

Donovia

The main goals of Donovia in its Arctic policy are to utilize its natural resources, protect its ecosystems, use the seas as a transportation system in Donovia's interests, and ensure that it remains a zone of peace and cooperation. Donovia currently maintains a military presence in the Arctic and has plans to improve it, as well as strengthen the Border Guard/Coast Guard presence there (see Military Variable). Using the Arctic for economic gain has been done by Donovia for centuries for shipping and fishing. Donovia has plans to exploit the large offshore resource deposits in the Arctic. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is of particular importance to the country for transportation, and the Donovian Security Council is considering projects for its development. The Security Council also stated a need for increasing investment in Arctic infrastructure. Donovia conducts extensive research in the Arctic region, notably the manned drifting ice stations and the Arktika 2007 expedition, which was the first to reach the seabed at the North Pole. The research is partly aimed to back up Donovia's territorial claims, in particular those related to its extended continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean.

Donovia likely will sustain diplomatic approach toward Arctic development to encourage multi-country cooperation regarding initiatives such as continental shelf claims and exploitation, and nautical logistical infrastructure. Despite ongoing tensions in other regions, Donovia maintains multilateral cooperation within the Arctic Council and other institutions regarding Arctic development. Multilateral cooperation facilities Arctic development projects and allows Donovia to maintain dialogue about its military buildup in the area. Continued diplomacy in the Arctic is essential to Donovia as it concedes that it cannot develop such a vast and challenging environment on its own.

In 2014, Donovia published a strategy paper for the development of the Arctic region and national security through 2028. This paper identifies six major development priorities for the Arctic region:

- Integrated socio-economic development of the Arctic zone of Donovia

- Development of science and technology

- Modernized information and telecommunication infrastructure

- Environmental security

- International cooperation in the Arctic

- Provision of military security, protection, and protection of the state border of Donovia in the Arctic

Donovia’s 2015 National Security Strategy supports the Arctic strategy and emphasizes the importance of international cooperation concerning Arctic issues. Public policy experts believe that Donovia has benefited from its cooperative stance by positioning itself to address collective transnational issues, such as oil spills, and enabling economic investments and collaboration.

Donovia has continued to work with other Arctic states both bilaterally and via the Arctic Council on non-military matters such as search and rescue efforts, economic efforts, scientific research, safety, and environmental exercises.

During an Arctic development meeting in March 2017, the President of Donovia stated that Donovia is open to partnerships with other countries on mutually beneficial projects such as natural resource development and global transport corridors.

United States

U.S. Arctic policy is based on the following principal objectives:

- National security

- Protecting the Arctic environment and conserving its living resources

- Ensuring environmentally-sustainable natural resource management and economic development in the region

- Strengthening institutions for cooperation among the Arctic nations

- Including the Arctic’s indigenous communities in decisions that affect them

- Enhancing scientific monitoring and research on local, regional, and global environmental issues On January 9, 2009, President Bush signed National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD)-66 on Arctic Region Policy. NSPD-66 is currently the active Arctic policy playbook being pursued by the U.S. The U.S. Arctic Policy Group is a federal interagency working group comprising those agencies with programs and/or involvement in research and monitoring, land and natural resources management, environmental protection, human health, transportation and policy making in the Arctic. The APG is chaired by the U.S. Department of State and meets monthly to develop and implement U.S. programs and policies in the Arctic, including those relevant to the activities of the Arctic Council. State Department’s Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs (OPA) is a part of the State Department’s Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs. OPA is responsible for formulating and implementing U.S. policy on international issues concerning the oceans, the Arctic, and Antarctica.

Canada

Canada has more Arctic land mass than any country. On 23 August 2010, Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper said protection of Canada's sovereignty over its northern regions was its number one and "non-negotiable priority" in Arctic policy. Canada's Northern Strategy priorities are:

- Exercise Arctic sovereignty

- Protect environmental heritage

- Promote social and economic development

- Improve and devolve northern governance

Denmark/Greenland/Faroe Islands

The Kingdom of Denmark is an Arctic nation with the importance of the Unity of the Realm with Denmark in Europe and the self-governing countries Greenland in the Arctic and the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic. Since Denmark is a member state of the European Union (EU), the Arctic policy of EU affected the development of the Kingdom of Denmark Strategy for the Arctic, 2011-2020.

The key elements of Denmark’s Arctic strategy are:

- Development that benefits the inhabitants of the by incorporating a fundamental respect for the Arctic peoples’ rights to utilize and develop their own resources as well as respect for the indigenous Arctic culture, traditions and lifestyles and the promotion of their rights

- An overall goal of preventing conflicts and avoiding the militarization of the Arctic

- A peaceful, secure, and safer Arctic

- Self-sustaining growth and development

- Development with respect for the Arctic’s vulnerable climate, environment and nature

- Close cooperation with our international partners Denmark and Greenland have an EEZ while an EEZ has not yet been declared in the Faroese fisheries territory. The Kingdom has submitted documentation to the CLCS for claims relating to two areas near the Faroe Islands and by 2014 plans to submit documentation on three areas near Greenland, including an area north of Greenland which, among others, covers the North Pole. The actual work of the project is a collaboration between Jarðfeingi (Faroe Directorate of Geology and Energy), the Danish Maritime Safety Administration, DTU Space (Institute for Space Research and Technology), National Survey and Cadastre and the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). Jarðfeingi, together with GEUS, is project manager for the Faroese Continental Shelf Project (half funded by the Faroe Islands) while GEUS is the project manager for the Greenland part where the Bureau of Minerals and Petroleum in Nuuk and the Arctic Science IntegrAtion Quest (ASIAQ) (Greenland’s Survey) take part.

Denmark’s priority for defense policy is to maintain the Arctic as an area of low tension and international cooperation. It sees the Baltic Sea as an area of higher threats and priorities than the Arctic.

Norway

Norway’s Arctic Strategy has five major priorities:

- International cooperation. The Arctic Council is the only circumpolar forum for political discussions at government level, and is attracting increasing attention outside the Arctic. 30 projects under EU cross-border programs involved participants from northern Norway.

- Business development. 24.5 billion Norwegian krone (NOK) was the value of fish exports from northern Norway in 2016. This amounts to around 60% of the region’s total exports of goods.

- Knowledge development. 16% of the companies in northern Norway face recruitment difficulties compared with 9% nationwide. 705 million NOK was spent on research relating to the Arctic through the Research Council of Norway ion 2016.

- Infrastructure. 40 billion NOK was allocated to investment projects in Norway’s three northernmost counties.

- Environmental protection and emergency preparedness. 1,831 high-risk vessels passed through Norwegian waters in 2016, according to the Vardø Vessel Traffic Service. These vessels are over 130 meters in length, vessels carrying dangerous or polluting cargo, including radioactive material, and vessels towing or pushing a tow where the combined length exceeds 200 meters. Of these, nearly 400 were oil tankers. Norway’s Arctic policy (Nordkloden) is interlinked with the government’s regional policy and includes input and development for the Sámi people. The Svalbard archipelago is a group of islands around halfway between Norway and the North Pole. Although part of the Kingdom of Norway, the exercise of sovereignty over the islands is subject to the terms of the 1920 Svalbard Treaty. The treaty extends rights of equal access and commercial exploitation to all of the 46 contracting parties. The treaty also specifically prohibits the establishment of a naval base or any fortifications or structures used for ‘warlike purposes’. A series of events over the past few years has sustained a level of tension on the islands. In 2015 Norway demanded an explanation when the Donovian Deputy Prime Minister flew into Svalbard, in defiance of a travel ban on a journey to the North Pole. In April 2016 Donovian special purpose forces instructors landed in Svalbard before holding a parachute exercise over the polar ice cap. It was reported as part of a major exercise that a simulated amphibious assault masked by extensive electronic warfare capabilities was conducted by Donovia against Svalbard. Around the same time the Donovian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov launched a new attack on a number Norway’s policies on Svalbard and linked the Norwegian position to the wider issue of the militarization and the stronger role of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the Arctic. As the “northern flank” of NATO, Norway takes a dual approach when dealing with Donovia. It continues bilateral cooperation while at the same time maintaining a policy of strong defense. Although Norway does not consider Donovia to be a direct threat, it has observed what it sees as the ‘new normal’ in the Arctic. In its annual assessment of current security threats the Norwegian Intelligence Service has said that growing Donovian presence in the Arctic has been an important part of its modernization program and it expects this presence to grow.

Torrike

Having missed out on the oil boom for geographic reasons, Torrike has sought to gain access to other potential areas of interest and is deeply interested in gaining access to the Arctic. When Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire had initially tried to retain northern Norway as this gave it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid‐90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of northern Norway. The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition. Torrike may consider radical plans to guarantee access.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom (UK) only recently has stated its policy concerning the Arctic, and for the first time specifically included a military component of that policy. It has identified the Arctic and the High North as an area of concern, largely due to the increasing Donovian military expansion. Currently the Antarctic has a higher priority than the Arctic, and the UK has chosen to not appoint an Arctic Ambassador to improve co-ordination of policy in Whitehall and bolster UK representation in Arctic affairs. The House of Commons Defense Committee recently called on Ministers of Parliament to improve the UK’s Arctic capabilities.[:File:///X:/CTID/0D-PROJECTS/DATE-Europe/Most Current Drafts/Arctic PMESII-PT/Arctic Political.docx# edn1 [i]] These recommendations include the following:

- Outline the under-ice capabilities of Royal Navy (RN) submarines and set out a policy for future exercises beneath the polar ice cap

- Explain the concept of operations for Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers deployed to the North Atlantic and High North

- Assess the role of the Albion-class amphibious assault ships in operations to defend NATO’s northern flank before deciding whether or not to keep them in service

- Ensure UK military aircraft have the range and resilience to sustain operations in the Arctic, and have been tested thoroughly in such environments

- Justify the decision to acquire only nine P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft for the Royal Air Force

- Reinstate the Royal Marines’ extreme cold weather training in northern Norway to ‘normal’ levels in 2019 The committee members noted the recent Donovian submarine activity in the North Atlantic surpassed the Warsaw Pact era activity, especially in the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) Gap. This activity coincides with the UK’s reduced anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities.

People’s Republic of Olvana (PRO)

The PRO has a growing interest in the Arctic region. It was granted observer status in the Arctic council in May 2013 and considers itself a near-Arctic nation. The PRO has declared its general preference for pursuing its economic agenda on a bilateral basis instead of through regional organizations such as the Arctic Council. PROs policy on the status of territorial waters and freedom of navigation in the western Pacific Ocean might be received poorly by the Arctic countries if it began to be implemented in the Arctic Ocean. Some have speculated concerning the potential linkage between Olvanan interest in the Arctic and its increasing international presence as a naval power. The Olvana People’s Navy (OPN) has successfully sent a small naval flotilla into the Bering Sea between Donovia and Alaska. The OPN made its first visits to Denmark, Bothnia, and Torrike around the same time. Having possessed a single icebreaker since the early 1990s, a second, larger nuclear-powered icebreaker is under construction. A recent report has suggested that the OPN may be considering future submarine operations in the Arctic. Olvanan cargo ships are sailing along the Northeast Passage as part of their self-declared “Polar Silk Road”. Olvana and South Torbia have been in a series of talks and negotiations on how to partner in Arctic development.

Iceland

Iceland’s policy on Arctic issues is anchored in a parliamentary resolution adopted unanimously by Althingi in the spring of 2011 which outlines 12 priority areas. They cover: “Iceland’s position in the region, the importance of the Arctic Council and the UNCLOS, climate change, sustainable use of natural resources and security and commercial interests. Emphasis is furthermore placed on neighbor-state collaboration with the Faroe Islands and Greenland as well as the rights of indigenous peoples.”[:File:///X:/CTID/0D-PROJECTS/DATE-Europe/Most Current Drafts/Arctic PMESII-PT/Arctic Political.docx# edn1 [i]]

Iceland has no standing military forces. There is a U.S. naval presence at Keflavik, and NATO provides Icelandic air policing. Iceland’s Arctic Affairs Policy is being debated due to concern over Donovian aggressiveness in the region, political differences concerning pro- and anti-NATO positions, and divisions over the EU.

Bothnia

Despite being a member of the Arctic Council, Bothnia has no written policy concerning the Arctic.

Otso

Despite being a member of the Arctic Council, Otso has no written policy concerning the Arctic.

[:File:///X:/CTID/0D-PROJECTS/DATE-Europe/Most Current Drafts/Arctic PMESII-PT/Arctic Political.docx# ednref1 [i]] “The Arctic Region.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government Offices of Iceland. Accessed 23 August 2018.

[:File:///X:/CTID/0D-PROJECTS/DATE-Europe/Most Current Drafts/Arctic PMESII-PT/Arctic Political.docx# ednref1 [i]] “On Thin Ice: UK Defence in the Arctic.” 15 August 2018.

[:File:///X:/CTID/0D-PROJECTS/DATE-Europe/Most Current Drafts/Arctic PMESII-PT/Arctic Political.docx# ednref1 [i]] Pinar Akcayoz De Neve, Adam Heal, and Henry Lee. “Security of the Arctic As the U.S. Takes Over the Arctic Council Leadership in 2015.” Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science. June 2015.

- ↑ Pinar Akcayoz De Neve, Adam Heal, and Henry Lee. “Security of the Arctic As the U.S. Takes Over the Arctic Council Leadership in 2015.” Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science. June 2015. https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/Arctic%20Security%20Policy%20Brief.pdf