Chapter 13: CBRN and Smoke

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.2 Opposing Force Tactics.

The use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons can have an enormous impact on all combat actions. Because chemical employment is more likely than the other three types, this chapter begins by focusing on OPFOR chemical capabilities. Because the OPFOR may also have some biological, nuclear, and radiological capabilities, these also deserve discussion, despite of the lower probability of their employment. The chapter concludes with discussions of CBRN protection and employment of smoke.

Contents

- 1 Weapons of Mass Destruction

- 2 Preparedness

- 3 Staff Responsibility

- 4 Chemical Warfare

- 5 Biological Warfare

- 6 Radiological Weapons

- 7 Nuclear Warfare

- 8 CBRN Protection

- 9 Smoke

Weapons of Mass Destruction

CBRN weapons are a subset of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), although the latter exclude the delivery means where such means is a separable and divisible part of the weapon. WMD are weapons or devices intended for or capable of causing a high order of physical destruction or mass casualties (death or serious bodily injury to a significant number of people). The casualty-producing elements of WMD can continue inflicting casualties on the enemy and exert powerful psychological effects on the enemy's morale for some time after delivery.

Existing types of WMD include chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons. However, technological advances are making it possible to develop WMD based on qualitatively new principles, such as infrasonic (acoustic) or particle-beam weapons. In addition, conventional weapons, such as precision weapons or volumetric explosives, can also take on the properties of WMD.

Preparedness

In response to foreign developments, the OPFOR maintains a capability to conduct chemical, nuclear, and possibly biological or radiological warfare. However, it would prefer to avoid the use of CBRN weapons by either side. This is especially true of nuclear and biological weapons, which have lethal effects over much larger areas than do chemical weapons. The effects of biological weapons can be difficult to localize and to employ in combat without affecting friendly forces. Their effects on the enemy can be difficult to predict. Unlike nuclear or biological weapons, chemical agents can be used to affect limited areas of the battlefield. The consequences of chemical weapons use are more predictable and thus more readily integrated into battle plans at the tactical level. In the event that either side resorts to CBRN weapons, the OPFOR is prepared to employ CBRN protection measures.

Multiple Options

Force modernization has introduced a degree of flexibility previously unavailable to combined arms commanders. It creates multiple options for the employment of forces at strategic, operational, and tactical levels with or without the use of CBRN weapons. Many of the same delivery means available for CBRN weapons can also be used to deliver precision weapons that can often achieve desired effects without the stigma associated with CBRN weapons.

The OPFOR might use CBRN weapons either to deter aggression or as a response to an enemy attack. It has surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs) capable of carrying nuclear, chemical, or biological warheads. Most OPFOR artillery is capable of delivering chemical munitions, and most systems 152-mm and larger are capable of firing nuclear rounds. Additionally, the OPFOR could use aircraft systems and cruise missiles to deliver a CBRN attack. The OPFOR has also trained special-purpose forces (SPF) as alternate means of delivering CBRN munitions packages.

The threat of using these systems to deliver CBRN weapons is also an intimidating factor. Should any opponent use its own CBRN capability against the OPFOR, the OPFOR is prepared to retaliate in kind. It is also possible that the OPFOR could use CBRN against a neighbor as a warning to any potential enemy that it is willing to use such weapons. The fact that CBRN weapons may also place noncombatants at risk is also a positive factor from the OPFOR’s perspective. Thus, it may use or threaten to use CBRN weapons as a way of applying political, economic, or psychological pressure by allowing the enemy no sanctuary.

Targeting

The OPFOR considers the following targets to be suitable for the employment of CBRN weapons:

- CBRN delivery means and their supply structure.

- Precision weapons.

- Prepared defensive positions.

- Reserves and troop concentrations.

- Command and control (C2) centers.

- Communications centers.

- Reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition centers.

- Key air defense sites.

- Logistics installations, especially port facilities.

- Airfields the OPFOR does not intend to use immediately.

Enemy CBRN delivery means (aircraft, artillery, missiles, and rockets) normally receive the highest priority. The suitability of other targets depends on the OPFOR’s missions, the current military and political situation, and the CBRN weapons available for use.

Staff Responsibility

On the functional staff of a division- or brigade-level headquarters, the chief of WMD is responsible for planning the offensive use of WMD, including CBRN weapons. (See the subsections on Release under Chemical Warfare, Nuclear Warfare, and Biological Warfare below.) The WMD staff element advises the command group and the primary and secondary staff on issues pertaining to CBRN employment. The WMD element receives liaison teams from any subordinate or supporting units that contain WMD delivery means.

CBRN defense comes under the chief of force protection. The force protection element of the functional staff may receive liaison teams from any subordinate or supporting chemical defense units. However, those units can also send liaison teams to other parts of the staff, as necessary (including, for example, the chief of reconnaissance).

Chemical Warfare

The OPFOR is equipped, structured, and trained to conduct both offensive and defensive chemical warfare. It is continually striving to improve its chemical warfare capabilities. It believes that an army using chemical weapons must be prepared to fight in the environment it creates. Therefore, it views chemical defense as part of a viable offensive chemical warfare capability. It maintains a large inventory of individual and collective chemical protection and decontamination equipment. (See the CBRN Protection portion of this chapter.)

Weapons and Agents

Virtually all OPFOR indirect fire weapons can deliver chemical agents. These delivery means include aircraft, multiple rocket launchers (MRLs), artillery, mines, rockets, and SSMs. Other possible delivery means could include SPF, affiliated insurgent or guerrilla organizations, or civilian sympathizers. For additional information on delivery systems, see the Worldwide Equipment Guide.

One way of classifying chemical agents according to the effect they have on persons. Thus, there are two major types, each with subcategories. Lethal agents, categorized by how they attack and kill personnel, include nerve, blood, blister, and choking agents. Nonlethal agents include incapacitants and irritants.

Nerve Agents

Nerve agents are fast-acting. Practically odorless and colorless, they attack the body’s nervous system, causing convulsions and eventually death. Nerve agents are further classified as either G- or V- agents. At low concentrations, the sarin (GB) series incapacitates. It kills if inhaled or absorbed through the skin. The rate of action is very rapid if inhaled, but slower if absorbed through the skin. V-agents produce similar effects, but are quicker-acting and more persistent than G-agents.

Blood Agents

Blood agents block the body’s oxygen transferal mechanisms, leading to death by suffocation. A common blood agent is hydrogen cyanide (AC). It kills quickly and dissipates rapidly.

Blister Agents

Blister agents, such as mustard (H) or lewisite (L) and combinations of these two compounds, can disable or kill after contact with the skin, being inhaled into the lungs, or being ingested. Contact with the skin can cause painful blisters, and eye contact can cause blindness. These agents are especially lethal when inhaled.

Choking Agents

Choking agents, such as phosgene (CG) and diphosgene (DP), block respiration by damaging the breathing mechanism, which can be fatal. As with blood agents, this type is nonpersistent, and poisoning comes through inhalation. Signs and symptoms of toxicity may be delayed up to 24 hours.

Incapacitants

Incapacitants include psychochemical agents and paralyzants. These agents can disrupt a victim’s mental and physical capabilities. The victim may not lose consciousness, and the effects usually wear off without leaving permanent physical injuries.

Irritants

Irritants, also known as riot-control agents, cause a strong burning sensation in the eyes, mouth, skin, and respiratory tract. The best known of these agents is tear gas (CS). Their effects are also temporary. Victims recover completely without having any serious aftereffects.

Agent Persistency

Chemical agents are also categorized according to their persistency. Generally, the OPFOR would use persistent agents on areas it does not plan to enter and nonpersistent agents where it does.

Persistent Agents

Persistent agents can retain their disabling or lethal characteristics from days to weeks, depending on environmental conditions. Aside from producing mass casualties initially, persistent agents can produce a steady rate of attrition and have a devastating effect on morale. They can seriously degrade the performance of personnel in protective clothing or impose delays for decontamination.

Nonpersistent Agents

Nonpersistent agents generally last a shorter period of time than persistent agents, depending on weather conditions. The use of a nonpersistent agent at a critical moment in battle can produce casualties or force enemy troops into a higher level of individual protective measures. With proper timing and distance, the OPFOR can employ nonpersistent agents and then have its maneuver units advance into or occupy an enemy position without having to decontaminate the area or don protective gear.

Other Toxic Chemicals

In addition to traditional chemical warfare agents, the OPFOR may find creative and adaptive ways to cause chemical hazards using chemicals commonly present in industry or in everyday households. In the right combination, or in and of themselves, the large-scale release of such chemicals can present a health risk, whether caused by military operations, intentional use, or accidental release.

Toxic Industrial Chemicals

Toxic industrial chemicals (TICs) are chemical substances with acute toxicity that are produced in large quantities for industrial purposes. Exposure to some industrial chemicals can have a lethal or debilitating effect on humans. They are a potentially attractive option for use as weapons of opportunity or WMD because of—

- The near-universal availability of large quantities of highly toxic stored materials.

- Their proximity to urban areas.

- Their low cost.

- The low security associated with storage facilities.

Employing a TIC against an opponent by means of a weapon delivery system, whether conventional or unconventional, is considered a chemical warfare attack, with the TIC used as a chemical agent. The target may be the enemy’s military forces or a civilian population.

In addition to the threat from intentional use as weapons, catastrophic accidental releases of stored industrial chemicals may result from—

- Collateral damage associated with military operations.

- Electrical power interruption.

- Improper facility maintenance or shutdown procedures.

These events are common in armed conflict and post-conflict urban environments.

The most important factors to consider when assessing the potential for adverse human health impacts from a chemical release are—

- Acute toxicity.

- Physical properties (volatility, reactivity, and flammability).

- The likelihood that large quantities will be accidentally released or available for exploitation. Foremost among these factors is acute toxicity.

The following are examples of high- and moderate-risk TICs. The risk assessment is based on acute toxicity by inhalation, worldwide availability (number of producers and number of countries where the substance is available), and physical state (gas, liquid, or solid) at standard temperature and pressure:

- High-risk. Ammonia, chlorine, fluorine, formaldehyde, hydrogen chloride, phosgene, and sulfuric acid.

- Moderate-risk. Carbon monoxide, methyl bromide, nitrogen dioxide, and phosphine.

This list does not include all chemicals with high toxicity and availability. Specifically, chemicals with low volatility are not included. Low-vapor pressure chemicals include some of the most highly toxic chemicals widely available, including most pesticides.

Some of the high-risk TICs are frequently present in an operational environment. Chlorine (water treatment and cleaning materials), phosgene (insecticides and fertilizers), and hydrogen cyanide are traditional chemical warfare agents that are also considered TICs. Cyanide salts may be used to contaminate food or water supplies. Hydrogen chloride is used in the production of hydrochloric acid. Formaldehyde is a disinfectant and preservative. Fluorine is a base element that is used to produce fluorocarbons. Fluorocarbons are any of various chemically inert compounds that contain both carbon and fluorine. Fluorocarbons are present in common products (refrigerants, lubricants, and nonstick coatings) and are used in the production of resins and plastics.

Household Chemicals

The OPFOR understands that some everyday household chemicals have incompatible properties that result in undesired chemical reaction when mixed with other chemicals. This includes substances that will react to cause an imminent threat to health and safety, such as explosion, fire, and/or the formation of toxic materials. For example, chlorine bleach, when mixed with ammonia, will generate the toxic gases chloramine and hydrazine that can cause serious injury or death. Another example of such incompatibilities is the reaction of alkali metals, such as sodium or potassium, with water. Sodium is commonly used in the commercial manufacture of cyanide, azide, and peroxide, and in photoelectric cells and sodium lamps. It has a very large latent heat capacity and is used in molten form as a coolant in nuclear breeder reactors. The mixture of sodium with water produces sodium hydroxide, which can cause severe burns upon skin contact.

Chemical Release

Among CBRN weapons, the OPFOR is most likely to use chemical weapons against even a more powerful enemy, particularly if the enemy does not have the capability to respond in kind. Since the OPFOR does not believe that first use of chemical agents against units in the field would provoke a nuclear response, it is less rigid than forces of other nations in the control of chemical release.

Initially, the use of chemical weapons is subject to the same level of decision as nuclear and biological weapons. At all levels of command, a chemical weapons plan is part of the fire support plan. Once the National Command Authority (NCA) has released initial authorization for the use of chemical weapons, commanders can employ them freely, as the situation demands. Then each commander at the operational-strategic command (OSC) and lower levels who has systems capable of chemical delivery can implement the chemical portions of his fire support plan, as necessary.

After a decision for nuclear use, the OPFOR can employ chemical weapons to complement nuclear weapons. However, the OPFOR perceives that chemical weapons have a unique role, and their use does not depend on initiation of nuclear warfare. It is possible that the OPFOR would use chemical weapons early in an operation or strategic campaign or from its outset. It would prefer not to use chemical weapons within its own borders. However, it would contaminate its own soil if necessary in order to preserve the regime or its sovereignty.

Offensive Chemical Employment

The basic principle of chemical warfare is to achieve surprise. It is common to mix chemical rounds with high-explosive (HE) rounds in order to achieve chemical surprise. Chemical casualties inflicted and the necessity of chemical protective gear degrade enemy defensive actions. The OPFOR also may use chemical agents to restrict the use of terrain. For example, contamination of key points along the enemy’s lines of communications can seriously disrupt his resupply and reinforcement. Simultaneously, it can keep those points intact for subsequent use by the attacking OPFOR.

Nonpersistent agents are suitable for use against targets on axes the OPFOR intends to exploit. While possibly used against deep targets, their most likely role is to prepare the way for an assault by maneuver units, especially when enemy positions are not known in detail. The OPFOR may also use nonpersistent agents against civilian population centers in order to create panic and a flood of refugees.

Persistent agents are suitable against targets the OPFOR cannot destroy by conventional or precision weapons. This can be because a target is too large or located with insufficient accuracy for attack by other than an area weapon. Persistent agents can neutralize such targets without a pinpoint attack.

In the offense, likely chemical targets include—

- Troops occupying defensive positions, using nonpersistent agents delivered by MRLs to neutralize these troops just before launching a ground attack. Ideally, these agents would be dissipating just as the attacking OPFOR units enter the area where the chemical attack occurred.

- CBRN delivery systems, troop concentration areas, headquarters, and artillery positions, using all types of chemical agents delivered by tube artillery, MRLs, SSMs, and aircraft.

- Bypassed pockets of resistance (especially those that pose a threat to the attacking forces), using persistent agents.

- Possible assembly areas for enemy counterattack forces, using persistent agents.

The OPFOR could use chemical attacks against such targets simultaneously throughout the enemy defenses. These chemical attacks combine with other forms of conventional attack to neutralize enemy nuclear capability, C2 systems, and aviation. Subsequent chemical attacks may target logistics facilities. The OPFOR would use persistent agents deep within the enemy’s rear and along troop flanks to protect advancing units.

Defensive Chemical Employment

When the enemy is preparing to attack, the OPFOR can use chemical attacks to—

- Disrupt activity in his assembly areas.

- Limit his ability to maneuver into axes favorable to the attack.

- Deny routes of advance for his reserves.

Once the enemy attack begins, the use of chemical agents can impede an attacking force. It can destroy the momentum of the attack by causing casualties or causing attacking troops to adopt protective measures. Persistent chemical agents can deny the enemy certain terrain and canalize attacking forces into kill zones.

Biological Warfare

The OPFOR closely controls information about the status of its biological warfare capabilities. This creates uncertainty among its neighbors and other potential opponents as to what types of biological agents the OPFOR might possess and how it might employ them.

Biological weapons can provide a great equalizer in the face of a numerically and/or technologically superior adversary that the OPFOR cannot defeat in a conventional confrontation. However, their effects on the enemy can be difficult to predict, and the OPFOR must also be concerned about the possibility that the effects could spread to friendly forces.

Weapons and Agents

Biological weapons consist of pathogenic microbes, micro-organism toxins, and bioregulating compounds. Depending on the specific type, these weapons can incapacitate or kill people or animals and destroy plants, food supplies, or materiel. The type of target being attacked determines the choice of agent and dissemination system.

Pathogens

Pathogens cause diseases such as anthrax, cholera, plague, smallpox, tularemia, or various types of fever. These weapons would be used against targets such as food supplies, port facilities, and population centers to create panic and disrupt mobilization plans.

Toxins

Toxins are produced by pathogens and also by snakes, spiders, sea creatures, and plants. Toxins are faster acting and more stable than live pathogens. Most toxins are easily produced through genetic engineering. Toxins produce casualties rapidly and can be used against tactical and operational targets.

Bioregulators

Bioregulators are chemical compounds that are essential for the normal psychological and physiological functions. A wide variety of bioregulators are normally present in the human body in extremely minute concentrations. These low-molecular-weight compounds, usually peptides (made up of amino acids), include neurotransmitters, hormones, and enzymes. Examples of bioregulators are—

- Insulin (a pancreatic protein hormone that is essential for the metabolism of carbohydrates).

- Enkephalin (either of two pentapeptides with opiate and analgesic activity that occur naturally in the brain and have a marked affinity for opiate receptors).

These compounds can produce a wide range of harmful effects if introduced into the body at higher than normal concentrations or if they have been altered. Psychological effects could include exaggerated fear and pain. In addition, bioregulators can cause severe physiological effects such as rapid unconsciousness and, depending on such factors as dose and route of administration, can also be lethal. Unlike pathogens, which take hours or days to act, bioregulators could act in only minutes. The small peptides, having fewer than 12 amino-acid groups, are most amenable to military application.

Agent Effects

Biological weapons are extremely potent and provide wide-area coverage. Some biological agents are extremely persistent, retaining their capabilities to infect for days, weeks, or longer. Biological weapons can take some time (depending on the agent) to achieve their full effect. To allow these agents sufficient time to take effect, the OPFOR may use clandestine means, such as SPF or civilian sympathizers, to deliver biological agents in advance of a planned attack or even before the war begins.

Delivery Means

It is possible to disseminate biological agents in a number of ways. Generally, the objective is to expose enemy forces to an agent in the form of a suspended cloud of very fine biological agent particles. Dissemination through aerosols, either as droplets from liquid suspensions or by small particles from dry powders, is by far the most efficient method. For additional information on delivery systems see the Worldwide Equipment Guide.

There are two basic types of biological munitions:

- Point-source bomblets delivered directly on targets.

- Line-source tanks that release the agent upwind from the target. Within each category, there can be multiple shapes and configurations.

Military systems, as well as unconventional means, can deliver biological agents. Potential delivery means include rockets, artillery shells, aircraft sprayers, saboteurs, and infected rodents. The OPFOR might use SPF, affiliated irregular forces, and/or civilian sympathizers to deliver biological agents within the region, outside the immediate region (to divert enemy attention and resources), or even in the enemy’s homeland.

Targets

Probable targets for biological warfare pathogen attack are enemy CBRN delivery units, airfields, logistics facilities, and C2 centers. The OPFOR may target biological weapons against objectives such as food supplies, water sources, troop concentrations, convoys, and urban and rural population centers rather than against frontline forces. The use of biological agents against rear area targets can disrupt and degrade enemy mobilization plans as well as the subsequent conduct of war. This type of targeting can also reduce the likelihood that friendly forces would become infected.

Biological Release

The decision to employ biological agents is a political decision made at the national level⎯by the NCA. Besides the political ramifications, the OPFOR recognizes a degree of danger inherent in the use of biological agents, due to the difficulty or controlling an epidemic caused by them.

The prolonged incubation period makes it difficult to track down the initial location and circumstances of contamination. Thus, there is the possibility of plausible deniability. Even if an opponent might be able to trace a biological attack back to the OPFOR, it may not be able to respond in kind.

Radiological Weapons

It is possible that the OPFOR may develop and employ radiological weapons whose effects are achieved by using toxic radioactive materials against desired targets. The purpose of employing radiological materials could be to achieve leverage or intimidation against regional neighbors. However, such weapons could also be used to deter intervention by extraregional forces or to disrupt such forces once deployed in the region. While they can be used as area denial, intimidation, and political weapons, radiological weapons are also considered weapons of terror.

A radiological weapon is any device, including weapon or equipment other than a nuclear explosive device, specifically designed to employ radioactive material by disseminating it to cause destruction, damage, or injury by means of the radiation produced by the decay of such material. Radiological weapons differ from chemical and biological weapons in that radiation cannot be “neutralized” or “sterilized” and many radiological materials have half-lives in years. Two general types of radiological weapons are radiological dispersal devices and radiological exposure devices.

Radiological Dispersal Devices

A radiological dispersal device (RDD) is an improvised assembly or process, other than a nuclear explosive device, designed to disseminate radioactive material in order to cause destruction, damage, or injury. Unlike nuclear weapons, RDDs do not produce a nuclear explosion. However, RDDs spread radioactive material contaminating personnel, equipment, facilities, and terrain. They kill or injure by exposing people to radioactive material. Victims are irradiated when they get close to or touch the material, inhale it, or ingest it. The actual dose rate depends on the type and quantity of radioactive material spread over the area, and contributing factors such as weather and terrain.

The OPFOR could disperse radioactive material using low-level radiation sources in a number of ways, such as—

- Arming the warhead of a conventional missile with active material from a nuclear reactor.

- Releasing low-level radioactive material intended for use in industry or medicine.

- Disseminating material from a research or power-generating nuclear reactor.

- Depositing a radioactive source in a water supply.

Dispersal of radioactive materials is inexpensive and requires limited resources and technical knowledge. The primary source for radioactive material used in the construction of RDDs is from nuclear power plants and radioactive materials used in hospitals.

One design of RDD, popularly called a “dirty bomb,” uses conventional explosives to disperse radioactive contamination. Any conventional or improvised explosive device can be used by placing it in close proximity to radioactive material. The explosion causes the dissemination of the radioactive material. A dirty bomb typically generates its immediate casualties from the direct effects of the conventional explosion (blast injuries and trauma). However, one of the primary purposes of a dirty bomb is to frighten people by contaminating their environment with radioactive materials and threatening large numbers of people with exposure. As an area denial weapon, an RDD can generate significant public fear and economic impact. In some cases, an area may not be habitable for nonmilitary personnel, but military operations could continue, with appropriate protective measures.

Radiological Exposure Devices

A radiological exposure device (RED) is a radioactive source placed to cause injury or death. In this case, rather than resulting from dispersed radioactive material, radioactive exposure results from discrete sources, such as a radioactive source concealed in a high traffic area. The placement of an RED may be covert in order to increase the potential dose if the source is not detected.

Nuclear Warfare

The OPFOR believes a war is most likely to begin with a phase of nonnuclear combat that may include the use of chemical weapons. The OPFOR emphasizes the destruction of as much as possible of enemy nuclear capability during this nonnuclear phase. To do so, it would use air and missile attacks; airborne, heliborne, and special-purpose forces; and rapid, deep penetrations by ground forces. The OPFOR hopes these attacks can deny the enemy a credible nuclear option.

Delivery Means

If the OPFOR decides to use nuclear weapons, the nuclear delivery systems may include aircraft from both national- and theater-level aviation, and SSMs. Most artillery 152-mm or larger is capable of firing nuclear rounds, if such rounds are available. Other possible delivery means could include SPF. The OPFOR may also choose to use affiliated forces for nuclear delivery. For additional information on nuclear delivery systems, see the Worldwide Equipment Guide.

Transition to Nuclear

Even when nuclear weapons are not used at the outset of a conflict, OPFOR commanders deploy troops based on the assumption that a nuclear-capable enemy might attack with nuclear weapons at any moment. The OPFOR continuously updates its own plans for nuclear employment, although it prefers to avoid nuclear warfare. As long as it achieves its objectives, and there are no indications that the enemy is going to use nuclear weapons, the OPFOR would likely not use them either. However, it could attempt to preempt enemy nuclear use by conducting an initial nuclear attack. Otherwise, any OPFOR decision to go nuclear would have to be made early in the conflict, so that sufficient nonnuclear power would remain to follow up and to exploit the gains of nuclear employment.

If any opponent were to use nuclear weapons against the OPFOR, the OPFOR would respond in kind, as long as it is still capable. The same would be true of any nuclear-capable opponent, if the OPFOR were the first to use nuclear means. While the OPFOR recognizes the advantage of its own first use, it may risk first use only when the payoff appears to outweigh the potential costs. Therefore, it will probably avoid the use of nuclear weapons against a more powerful enemy unless survival of the regime or the nation is at stake.

The OPFOR is probably more likely to use its nuclear capability against a less powerful opponent. The likelihood increases if that opponent uses or threatens to use its own nuclear weapons against the OPFOR or does not have the means to retaliate in kind. This could account for a nuclear or nuclear- threatened environment existing at the time a more powerful force might choose to intervene.

Types of Nuclear Attack

The OPFOR categorizes nuclear attacks as either massed or individual attacks. The category depends on the number of targets hit and the number of nuclear munitions used.

A massed nuclear attack employs multiple nuclear munitions simultaneously or over a short time interval. The goal is to destroy a single large enemy formation, or several formations, as well as other important enemy targets. A massed attack can involve a single service of the Armed Forces, as in a nuclear missile attack by the Strategic Forces, or the combined forces of different services.

An individual nuclear attack may hit a single target or group of targets. The attack consists of a single nuclear munition, such as a missile or bomb.

Nuclear Release

At all stages of a conflict, the OPFOR keeps nuclear-capable forces ready to make an attack. The decision to initiate nuclear warfare is a political decision made at the national level.

After the initial nuclear release, the NCA may delegate employment authority for subsequent nuclear attacks to an OSC commander. The commander of the OSC’s integrated fires command submits recommendations for the subsequent employment of nuclear and chemical weapons to the OSC commander for approval and integration into OSC fire support plans.

Offensive Nuclear Employment

Once the NCA releases nuclear weapons, two principles govern their use: mass and surprise. The OPFOR plans to conduct the initial nuclear attack suddenly and in coordination with nonnuclear fires. Initial nuclear attack objectives are to destroy the enemy’s main combat formations, C2 systems, and nuclear and precision weapons, thereby isolating the battlefield.

Nuclear attacks target and destroy the enemy’s defenses and set the conditions for an exploitation force. Other fire support means support the assault and fixing forces. The OPFOR may plan high-speed air and ground offensive actions to exploit the nuclear attack.

If the enemy continues to offer organized resistance, the OPFOR might employ subsequent nuclear attacks to reinitiate the offense. Nuclear attacks can eliminate the threat of a counterattack or clear resistance from the opposite bank in a water obstacle crossing. If the enemy begins to withdraw, the OPFOR plans nuclear attacks on choke points where retreating enemy forces present lucrative targets.

Planning

Although the opening stages of an offensive action are likely to be conventional, OPFOR planning focuses on the necessity of—

- Countering enemy employment of nuclear weapons.

- Maintaining the initiative and momentum.

- Maintaining fire superiority over the enemy (preempting his nuclear attack, if necessary).

When planning offensive actions, the OPFOR plans nuclear fires in detail. Forces conducting the main attack would probably receive the highest percentage of weapons. However, the OPFOR may also reserve weapons for other large, important targets. In more fluid situations, such as during exploitation, the commander may keep some nuclear weapon systems at high readiness to fire on targets of opportunity. Nuclear allocations vary with the strength of the enemy defense and the scheme of maneuver.

Since the enemy too is under nuclear threat, he also must disperse his formations, which can make him more vulnerable to penetration by an attacking force. However, the OPFOR realizes that enemy troops are also highly mobile and capable of rapidly concentrating to protect a threatened area. Therefore, it considers surprise and timing of offensive actions to be extremely critical in order to complicate enemy targeting and deny him the time to use his mobility.

Execution

Upon securing a nuclear release, the OPFOR would direct nuclear attacks against the strongest points of the enemy’s formations and throughout his tactical and operational depth. This would create gaps through which maneuver units, in “nuclear-dispersed” formations, would attack as an exploitation force. As closely as safety and circumstances permit, maneuver forces follow up on attacks near the battle line. Airborne troops may exploit deep attacks.

An exploitation force would probably attack to take full advantage of the speed of advance it could expect to achieve. The aim of these maneuver units would be to seize or neutralize remaining enemy nuclear weapons, delivery systems, and C2 systems. By attacking from different directions, the maneuver units would try to split and isolate the enemy.

Commanders would ensure a rapid tempo of advance by assigning tank and mechanized infantry units to the exploitation force. Such units are quite effective in this role, because they have maneuverability, firepower, lower vulnerability to enemy nuclear attacks, and the capability to achieve penetrations of great depth.

Defensive Nuclear Employment

Primary uses of nuclear weapons in the defense are to—

- Destroy enemy nuclear and precision weapons and delivery means.

- Destroy main attacking groups.

- Conduct counterpreparations.

- Eliminate penetrations.

- Support counterattacks.

- Deny areas to the enemy.

If nuclear weapons degrade an enemy attack, the OPFOR could gain the opportunity to switch quickly to an offensive role.

CBRN Protection

Due to the proliferation of CBRN weapons, the OPFOR must anticipate their use, particularly the employment of chemical weapons. OPFOR planners believe that the best solution is to locate and destroy enemy CBRN weapons, delivery systems, and their supporting infrastructure before the enemy can use them against the OPFOR. In case this fails and it is necessary to continue combat actions despite the presence of contaminants, the OPFOR has developed and fielded a wide range of CBRN detection and warning devices, individual and collective protection equipment, and decontamination equipment. The OPFOR conducts rigorous training for CBRN defense.

OPFOR planners readily admit that casualties would be considerable in any future war involving the use of CBRN weapons. However, they believe that the timely use of active and passive measures can significantly reduce a combat unit’s vulnerability. These measures include but are not limited to protective equipment, correct employment of reconnaissance assets, and expeditious decontamination procedures. Other operational-tactical responses to the threat include⎯

- Dispersion: Concentrations must last for as short a time as possible.

- Speed of advance: If the advance generates enough momentum, this can make enemy targeting difficult and keep enemy systems on the move.

- Camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D): C3D measures complicate enemy targeting.

- Continuous contact: The enemy cannot attack with CBRN weapons as long as there is intermingling of friendly and enemy forces.

Organization

OPFOR chemical defense units are responsible for biological, radiological, and nuclear, as well as chemical, protection and reconnaissance measures. In the administrative force structure, such units are subordinate to all maneuver units brigade and above. During task-organizing, tactical-level commands may also receive additional chemical defense units allocated from the OSC or higher-level tactical command. However, those higher headquarters typically retain some chemical defense assets at their respective levels to deal with the threat to the support zone and provide chemical defense reserves.

Note. OPFOR “chemical troops” and “chemical defense” units also perform biological, radiological, and nuclear protection functions. For example, a chemical defense battalion at division or higher level contains a CBRN reconnaissance company. Likewise, a chemical defense platoon at brigade level has a CBRN reconnaissance squad.

Chemical troops are a vital element of combat support. They provide trained specialists for chemical defense units and for units of other arms. Basic tasks chemical troops can accomplish in support of combat troops include⎯

- Reconnoitering known or likely areas of CBRN contamination.

- Warning troops of the presence of CBRN contamination.

- Monitoring changes in the degree of contamination.

- Monitoring the CBRN contamination of personnel, weapons, and equipment.

- Performing decontamination activities.

- Providing trained troops to handle chemical munitions.

They perform specialized CBRN reconnaissance in addition to supporting regular ground reconnaissance efforts described in chapter 8.

CBRN protection functions are not limited to maneuver units. Artillery and air defense brigades have their own chemical defense units. Medical and SSM units have some decontamination equipment. Engineer troops also are important, performing functions such as decontaminating roads, building bypasses, and purifying water supplies. Of course, all arms have a responsibility for CBRN reconnaissance and at least partial decontamination without specialist support. However, they can continue combat actions for only a limited time without complete decontamination by chemical troops.

Equipment

OPFOR troops have protective clothing. Most combat vehicles and many noncombat vehicles have excellent overpressure and filtration systems. Items of equipment for individual or collective protection are adequate to protect soldiers from contamination for hours, days, or longer, depending on the nature and concentration of the contaminant. Antidotes provide protection from the effects of agents. Agent detector kits and automatic alarms are available in adequate quantities and are capable of detecting all standard agents.

Chemical troops have a wide variety of dependable equipment that, for the most part, is in good supply and allows them to accomplish a number of tasks in support of combat troops. They have specialized equipment for detecting and monitoring CBRN contamination. They have some specialized CBRN reconnaissance vehicles, and they may use helicopters for CBRN reconnaissance. Decontamination equipment is also widely available.

Reconnaissance

Under the guidance of the brigade-level chief of force protection, CBRN instructors in maneuver battalions and other units subordinate to the brigade train additional combat, combat support, and combat service support troops for CBRN observation and reconnaissance missions. Medical personnel also have instruments to check casualties for CBRN contamination.

Chemical defense personnel assigned to reconnaissance elements of chemical defense units perform CBRN reconnaissance. This involves two general types of activity: CBRN observation posts (OPs) and CBRN reconnaissance patrols. Such posts and patrols may augment any maneuver unit down to company level.

CBRN Observation Posts

A maneuver battalion or higher commander normally designates a CBRN OP to locate near his forward command post (CP). At division, brigade, or tactical group level, such a CBRN OP is normally manned by four to six CBRN specialists. These would typically be specially trained specialists from one squad of the CBRN reconnaissance platoon of a division’s chemical defense battalion or the CBRN reconnaissance squad of a brigade’s chemical defense platoon. In some cases, the CBRN OP at division or division tactical group (DTG) level might comprise an entire CBRN reconnaissance platoon. Most likely, a brigade or brigade tactical group (BTG) commander would keep one team of the CBRN reconnaissance squad from his chemical defense platoon to man the CBRN OP near his forward CP. However, he could employ the whole squad.

Since no chemical defense units are organic below brigade level, each maneuver battalion or company normally has a small team of additional-duty CBRN specialists. These company- and battalion- level specialists perform limited CBRN reconnaissance when CBRN support is not available from brigade or BTG level. When chemical troops are not available, virtually every company- or battery-size combat, combat support, and combat service support unit can establish its own CBRN OP using its own troops trained as observers. This OP is normally near the unit’s CP or command and observation post.

The functions of CBRN OPs are to⎯

- Detect CBRN contamination.

- Determine radiation levels and types of toxic substances.

- Monitor the drift of radioactive clouds.

- Report CBRN information and meteorological data to higher headquarters.

- Give a general alarm to threatened troops.

When stationary, a CBRN OP is normally in a camouflaged trench or a dug-in CBRN reconnaissance vehicle. During movement, it moves in its own vehicle close to the combat unit commander. The observers immediately activate CBRN detection devices after an enemy overflight, missile burst, or artillery shelling.

CBRN Reconnaissance Patrols

A CBRN reconnaissance patrol allocated to a maneuver, reconnaissance, or security element receives instructions from that unit’s commander. That commander tells the CBRN reconnaissance patrol leader of any specific areas to reconnoiter, the time for doing so, and the procedures for reporting the results. A patrol may also receive reconnaissance assignments from the brigade or division chief of force protection.

When operating in CBRN reconnaissance patrols, chemical defense personnel travel in reconnaissance vehicles specially equipped with CBRN detection and warning devices. Before a patrol begins its mission, its personnel check their individual CBRN protection equipment and detection instruments. They also examine the CBRN and communications equipment located on their reconnaissance vehicle.

As a patrol performs its mission, a designated crewman observes the readings of the onboard CBRN survey meters. Upon discovering radioactive or chemical contamination, the patrol determines the size and boundaries of the contaminated area and the radiation level or type of toxic substance present. The patrol leader then plots contaminated areas on his map, reports by radio to his commander, and orders his patrol to mark the contaminated area. The patrol designates bypass routes around contaminated areas or finds routes (with the lowest levels of contamination) through the area.

The OPFOR can also use helicopters to perform CBRN reconnaissance. Helicopters equipped with chemical and radiological area survey instruments are particularly useful for performing reconnaissance of areas with extremely high contamination levels.

Augmentation to Other Reconnaissance and Security Elements

CBRN reconnaissance elements are often allocated to maneuver units, sometimes becoming part of a security element or various types of reconnaissance patrol. A maneuver battalion (particularly one acting independently) may receive chemical troops allocated from the brigade-level chemical defense company or platoon. The resulting battalion-size detachment would typically use these chemical augmentees as part of a platoon-size fighting patrol.

CBRN Detection and Warring Reports

The OPFOR transmits CBRN warning information over communications channels in a parallel form using both the command net and the air defense and CBRN warning communications net. Depending of what type of unit initially detected the contamination, detection reports leading to such warnings may go either through chemical defense and force protection channels or through the maneuver unit or ground reconnaissance reporting chain.

Detection Reports

When chemical defense units establish CBRN OPs or CBRN reconnaissance patrols, these reconnaissance elements report through the chemical defense and force protection chain. Upon detection of contamination, a CBRN observer or CBRN reconnaissance patrol normally transmits a CBRN detection report to the commander of the parent chemical defense unit that dispatched it and (if capable and directed to do so) possibly to the chief of force protection (or chief of staff) on the staff of the commander to whom the chemical defense unit is subordinate or supporting. In any case, the chemical defense unit commander transmits the report to the chief of force protection of the maneuver division, brigade, or tactical group.

When CBRN observers (whether from the chemical troops or another branch) are allocated to regular ground reconnaissance elements, security elements, or maneuver units, the CBRN element that detects contamination would initially pass the detection report through reconnaissance or maneuver unit reporting channels. Of course, they would report the detection to the commander of the unit to which they are allocated.

Note. If the CBRN augmentees have their own special CBRN reconnaissance vehicles and associated radios, they can also send CBRN detection reports back to their parent chemical defense unit or the chief of force protection.

A ground reconnaissance or security element would pass the detection report to the unit that dispatched it. For example, a reconnaissance patrol leader would transmit the detection information via reconnaissance reporting channels to his parent reconnaissance unit commander and possibly by skip- echelon communications to the chief of reconnaissance at brigade, division, or tactical group level. The reconnaissance unit commander or chief of reconnaissance would then ensure that the chief of staff and/or chief of force protection at his level receives the CBRN detection report and takes appropriate action. When a maneuver unit chief of staff or chief of reconnaissance receives a CBRN detection report through his own channels, he immediately passes it to the chief of force protection at that level (or to the next- higher level that has one).

Similarly, upon detection of contamination, a CBRN observer in a fighting patrol (FP) would transmit a CBRN detection report to the FP leader. The FP leader would use the battalion command net to transmit the report to the maneuver battalion commander who sent out the FP. Using the brigade command net, the maneuver battalion commander would inform the maneuver brigade commander (or chief of staff) of the CBRN detection report. The brigade commander (or chief of staff) would consult with his chief of force protection. Based on the finding of the chief of force protection, both he and the brigade commander (or chief of staff) could then disseminate the CBRN warning report using their respective communications nets.

Warning Reports

The chief of force protection and his staff evaluate the CBRN detection report and determine whether it warrants the issuing of a warning. If it does, they inform the maneuver commander (or his chief of staff). At this point, the CBRN detection report changes to a CBRN warning report. Then, for example, the maneuver brigade commander (or chief of staff) disseminates a CBRN warning report via the brigade command net to all subordinate unit commanders, and via the division command net to the division commander and commanders of other brigades and other division subordinates. Simultaneously, the brigade chief of force protection disseminates the same CBRN warning report to all the brigade’s units over the air defense and CBRN warning communications net. He would also inform the division chief of force protection. The desired goal is to rapidly disseminate CBRN warning reports as soon as possible to all affected units.

The division or brigade chief of force protection (and/or the chief of staff) may issue an advance CBRN warning based on the predicted development of a CBRN situation. CBRN protective measures would change or be rescinded based on subsequent CBRN detection reports or on warning reports from higher, lower, or adjacent units. Changes in the CBRN protective measures are disseminated by the maneuver division or brigade commander (or chief of staff) and the chief force protection using their respective communications nets.

Decontamination

The OPFOR distinguishes between two types of decontamination of personnel and equipment: partial and complete. It tries to perform one or both as soon after exposure as possible. It also conducts decontamination of terrain and movement routes.

Partial Decontamination

OPFOR doctrine dictates that a combat unit should conduct a partial decontamination with its own equipment no later than 1 hour after exposure to contamination. This entails a halt while troops decontaminate themselves and their clothing, individual weapons, crew-served weapons, and vehicles. When forced to conduct partial decontamination in the contaminated area, personnel remain in CBRN protective gear. Following the completion of partial decontamination, the unit resumes its mission.

Complete Decontamination

The commander of a maneuver unit directs complete decontamination when the unit has already completed its mission but is still tactically dispersed. This type of decontamination involves the decontamination of the entire surface of a contaminated piece of equipment. This usually requires special decontamination stations established by decontamination units. Under some circumstances, however, it may be accomplished by troops using individual decontamination kits.

Chemical defense troops usually perform complete decontamination of maneuver units. Decontamination units of chemical defense platoons, companies, and battalions can operate either as a whole or in smaller elements. For example, the decontamination company of a chemical defense battalion may function independently. It may be separated from the rest of the battalion by as much as 20 km to decontaminate elements of a maneuver battalion or brigade-size force.

Decontamination units deploy to uncontaminated areas where contaminated units are located. They set up near movement routes or establish centrally located decontamination points to serve several troop units. Before deploying his equipment, the commander of a decontamination unit dispatches a reconnaissance element to select a favorable site, mark areas for setting up the equipment, and mark entry and exit routes.

Site selection depends on local features such as nearby roads, cross-country routes, and sources of uncontaminated water. Another selection criterion is the availability of camouflage, cover, and concealment. If natural concealment is insufficient, smokescreening of the site can provide camouflage. After decontamination stations are set up, the decontamination unit commander establishes security. The supported unit can also assign personnel to assist in providing security for the site.

Terrain and Route Decontamination

Decontamination of maneuver routes is necessary if OPFOR units cannot safely bypass or cross the contaminated routes. The first priorities for decontamination are routes (cross-country and roads) on the primary axes of advance. The OPFOR decontaminates terrain by either removing or covering the contaminated soil or by spraying liquid decontaminate by specially designed decontamination vehicles.

For radiological decontamination, engineer earthmoving equipment can remove the contaminated top layer of soil. An alternative is to cover the area with uncontaminated materials (soil, wood, or other surfacing materials). Similarly, one means of decontamination and disinfection of chemical and biological agents would be to remove a 3- to 4-cm layer of contaminated ground.

Another means of chemical or biological decontamination is the use of terrain decontamination vehicles. These truck-mounted systems can decontaminate or disinfect an area 5 m wide and 500 m long with a single load of decontamination solvent. After decontaminating a route or area, chemical defense troops must decontaminate or disinfect their own equipment.

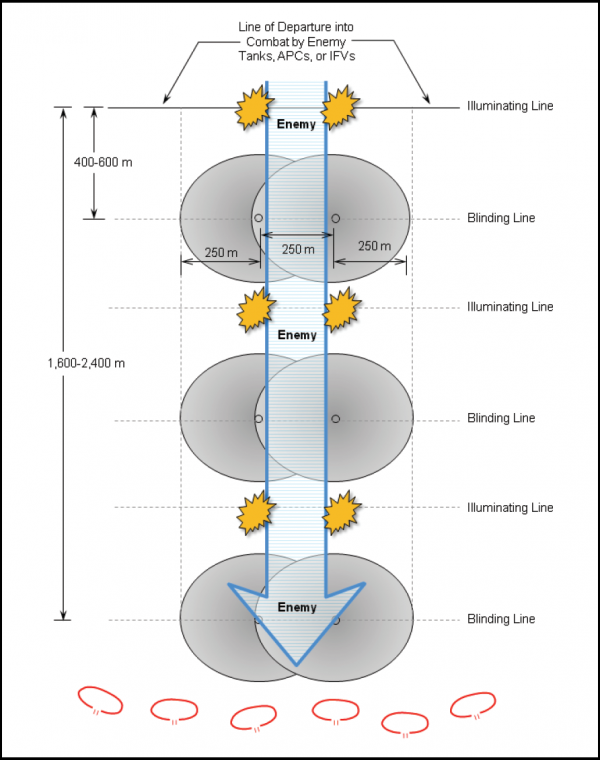

For terrain sector decontamination, chemical defense units equipped with decontamination trucks assemble near the contaminated area. When decontaminating or disinfecting sectors of terrain, they divide the sector into strips. The vehicles move on parallel axes using an echelon-right or echelon-left formation with the lead vehicle downwind from the others. Individual vehicles move at a distance of 30 to 50 m behind one another, but to the left or right just far enough that the covered strips slightly overlap. See figure 13-1.

For road decontamination, the decontamination vehicles form a column, with each vehicle assigned a sector of road. If the road is more than 5 m wide, then two or three vehicles form an echelon- right or echelon-left formation (as used in terrain sector decontamination). Jet engine-type decontamination vehicles are useful for decontaminating hard-surface roads or runways.

Recovery Activities

Commanders at all levels plan for restoring units that fall victim to CBRN attacks. This plan includes⎯

- Restoring C2.

- Reconnoitering the target area.

- Locating and rescuing casualties.

- Decontaminating personnel and equipment.

- Evacuating casualties.

- Evacuating weapons and combat equipment.

- Repairing vehicles.

- Clearing obstructions.

- Extinguishing fires.

To perform these tasks, the maneuver unit commander forms a recovery detachment. Depending on the situation and availability of forces, recovery detachments either come from subordinate units or from the reserves of a higher headquarters. If formed from subordinate units, recovery detachments generally are formed from the maneuver unit’s reserve. Regardless of origin, they include chemical reconnaissance and decontamination assets, engineers, medical and vehicle-repair personnel, and infantry troops (for labor and security).

CBRN reconnaissance patrols normally reach the area of destruction first, to establish the nature and extent of contamination. Priority for decontamination and recovery help goes to personnel and equipment easily returned to combat.

The recovery detachment commander selects locations for setting up a medical point, CBRN decontamination station, damaged vehicle collection point, and an area for reconstituting units. He also designates routes to and from the area, for reinforcement and evacuation. He then reports to his next-higher commander on the situation and the measures taken. Meanwhile, engineers assigned to the detachment clear rubble, extinguish fires, rescue personnel, and build temporary roads.

The final step consists of reconstituting units and equipping them with weapons and combat vehicles. While the recovery detachment performs its mission, unaffected elements provide security against any further enemy activity.

Smoke

The OPFOR plans to employ smoke extensively on the battlefield whenever the situation permits. Use of smoke can make it difficult for the enemy to conduct observation, determine the true disposition of OPFOR troops, and conduct fires (including precision weapon fires) or air attacks. The presence of toxic smokes may cause the enemy to use chemical protection systems, thus lowering his effectiveness, even if the OPFOR is using only neutral smoke.

Organization

In the administrative force structure, army groups, armies, and corps typically have smoke companies in their chemical defense battalions and/or smoke battalions. In either case, the smoke companies each consist of 12 smoke-generator trucks and 12 smoke-generator trailers. The generators carried on the trailers can be towed by combat vehicles or may be mounted on other vehicles. The smoke companies also have assorted smoke pots, drums, barrels, and grenades. The decontamination company subordinate to a chemical defense battalion has some systems that can also generate large-scale protective smokescreens as a secondary mission and may augment a smoke battalion or company when required. These smoke-generating assets are often allocated to OSCs, which can then suballocate them to tactical- level subordinates. For additional information, see FM 7-100.4.

Agents

The OPFOR employs a mix of smoke agents and their delivery systems, as well as improvised obscurants to generate obscuration effects. Smoke agents may be either neutral or toxic. Neutral smoke agents are liquid agents, pyrotechnic mixtures, or phosphorus agents with no toxic characteristics. Toxic smokes (commonly referred to as combination smoke) may include tear gas or other agents. They degrade electro-optical (EO) devices in the visual and near-infrared (IR) wavebands. They can also debilitate an unmasked soldier by inducing watering of the eyes, vomiting, or itching.

Some of these smokes and other obscurants contain toxic compounds and known or suspected carcinogens. A prolonged exposure to obscurants in heavy concentrations can have toxic effects. The toxic effect of exposure to fog oil particles is uncertain and, as is true of all smokes, depends heavily upon dose, time, and frequency of exposure.

The more common obscurants used by the OPFOR include⎯

- Petroleum smokes (fog oil and diesel fuel).

- Hexachloroethane (HC) or hexachlorobenzene (HCB) smoke.

- Aluminum-magnesium alloy smoke (Type III IR for bispectral effects⎯visual/IR bands).

- Phosphorus: white phosphorus (WP), red phosphorus (RP), WP/butyl mix (PWP).

- Metallic (including graphite or brass) smokes for millimeter wave (MMW) band and multispectral effects.

- Improvised obscurants including colored signal smokes, dust, and burning tires and oil wells.

The OPFOR recognizes the need to counter target acquisition and guidance systems operating in the IR and microwave regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. It has fielded obscurants, including chaff, capable of attenuating such wavelengths. Table 13-1 shows several example EO systems defeated by obscurants.

| Spectral Region | Optical/Electro-Optical System | Type of Obscurant |

|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet

1 nm-0.4 mm |

Developmental Sensors and Weapon Systems | Developmental Obscurants |

| Visible

0.4 mm-0.8 mm |

Viewers:

- Naked Eye - Day Sights, Optics - Camera Lens - EO Systems, Including Charged- Coupled Device (CCD) cameras - Battlefield TV and CCD TV ATGMs with Daylight Beacons |

All

NOTE: Obscurants can counter or degrade nighttime use of visual band illumination—including spotlights, flares, flashlights, and vehicle lights. |

| Near-IR

0.8 mm-1.3 mm |

Viewers:

- SACLOS ATGM Trackers - Night Vision (Image Intensifiers, IR) - CCD, aka Low-Light-level (LLL) TV Sensors: - Laser Designators, ND-Yag Laser - Laser Rangefinders, ND-Yag Laser |

All

NOTE: Obscurants can counter or degrade nighttime use of IR band illumination— including spotlights, flares, and night vision systems. |

| Short-Wave IR 1.3 mm-2.5 mm | Sensors:

- Laser Rangefinders, Other Lasers - Laser Designators, Other Lasers |

WP, PWP, RP, Dust, Type III

IR Obscurant |

| Mid-IR

2.50 mm-7 mm |

Viewers and Sensors (3-5mm):

- Thermal Imagers - Terminal Homing Missiles |

WP, PWP, RP, Dust, Type III

IR Obscurant |

| Far-IR

7 mm-15 mm |

Viewers and Sensors (8-12mm):

- Thermal Imagers - Terminal Homing Missiles |

WP and PWP (Instantaneous Interruption Only),

Dust, Type III IR Obscurant |

| Millimeter Wave-Lower Frequency

300 GHz-30 GHz |

Radars

Communication Systems |

MMW Band and Multispectral Obscurants |

| ATGM antitank guided missile GHz gigahertz ND neodymium nm nanometer

SACLOS semiautomatic command-to-line-of-sight guidance TV television mm micrometer | ||

As shown in table 13-1, smokes may operate in more than one band of the spectrum. The OPFOR is capable of employing obscurants effective in the visible through far-IR wavebands as well as portions of the MMW band. These obscurants are commonly referred to as multispectral smoke. The OPFOR uses a number of different smoke agents together for multispectral effects. For instance, an obscurant such as fog oil blocks portions of the electromagnetic spectrum more fully when seeded with chaff. The vast quantities of WP on the battlefield also suggest that random mixtures of this agent with other obscurants (both manmade and natural) could occur, by chance or design.

Delivery Systems

The OPFOR has an ample variety of equipment for smoke dissemination. Its munitions and equipment include—

- Smoke grenades.

- Vehicle engine exhaust smoke systems (VEESS).

- Smoke barrels, drums, and pots.

- Mortar, artillery, and rocket smoke rounds.

- Spray tanks (ground and air).

- Smoke bombs.

- Large-area smoke generators (ground and air).

- Improvised means (such as setting fires in forests, urban areas, fields, or oil soaked ground).

Although not designed for this purpose, some decontamination vehicles with chemical defense units can also generate smoke.

Smoke grenades include hand grenades, munitions for various grenade launchers, and smoke grenade-dispensing systems on armored vehicles. These grenades can provide quick smoke on the battlefield or fill gaps in smokescreens established by other means. Some armored fighting vehicles have forward-firing smoke grenade dispensers that can produce a bispectral screen up to 300 m ahead of vehicles.

All armored fighting vehicles can generate smoke through their exhaust systems. With these VEESS-equipped vehicles, a platoon can produce a screen that covers a battalion frontage for 4 to 6 minutes.

Smoke-filled artillery projectiles, smoke bombs, spray tanks, and generator systems are also common. Artillery can fire WP rounds (which have a moderate degrading effect on thermal imagers and a major one on lasers). The OPFOR makes considerable use of smoke pots emplaced by chemical troops, infantrymen, or other troops. The OPFOR still uses smoke bombs or pots dropped by fixed- or rotary-wing aircraft. For additional information on smoke systems, see the Worldwide Equipment Guide.

Types of Smokescreens

The OPFOR recognizes three types of smokescreens: blinding, camouflage, and decoy. Classification of each type as frontal, oblique, or flank depends on the screen’s placement. Smokescreens are either stationary or mobile depending on prevailing winds and the dispensing means used. Each basic type can serve a different purpose. However, simultaneous use of all types is possible.

Blinding

Blinding smokescreens can mask friendly forces from enemy gunners, OPs, and target-acquisition systems. They can restrict the enemy’s ability to engage the OPFOR effectively. Delivery of WP and plasticized white phosphorus (PWP) is possible using MRLs, artillery, mortars, fixed-wing aircraft, or helicopters. The OPFOR lays blinding smoke directly in front of enemy positions, particularly those of antitank weapons and OPs. Blinding smoke can reduce casualties significantly, since it can reduce an enemy soldier’s ability to acquire targets by a factor of 10.

Blinding smokescreens are part of the artillery preparation before an attack and the fires in support of the attack. Likely targets are enemy defensive positions, rear assembly areas, counterattacking forces, and fire support positions. The screening properties of a blinding smokescreen can couple with dust, HE combustion effects, and the incendiary effects of phosphorus. This can create an environment in which fear and confusion add to the measured effectiveness of the smoke.

Camouflage

The OPFOR uses camouflage smokescreens to support all kinds of C3D measures. Such screens can—

- Cover maneuver.

- Conceal the location of units.

- Hide the nature and direction of attacks.

- Mislead the enemy regarding any of these.

The camouflage smokescreen is useful on or ahead of friendly troops. These screens are normally effective up to the point where forces deploy for combat. The number, size, and location of camouflage smokescreens vary depending on terrain, weather, and type of combat action. Camouflage also forces enemy attack helicopters to fly above or around a screen, thus exposing themselves to attack. Camouflage smoke can also cover assembly areas, approaches of exploitation forces, or withdrawals. Smokescreens can also cover a wide surface area around fixed installations or mobile units that do not move for extended periods.

Establishing camouflage smokescreens normally requires use of a combination of smoke grenades, smoke barrels, smoke pots, vehicles (and trailers) mounting smoke generating devices, and aircraft. Some decontamination vehicles also have the capability to generate smoke.

Two smoke-generator vehicles can lay a smokescreen of sufficient size to cover a battalion advancing to the attack. For larger smokescreens, the OPFOR divides the smokescreen line into segments and assigns two vehicles to each segment. Doctrinally, camouflage smokescreens should cover an area at least five times the width of the attacking unit’s frontage.

The threat of enemy helicopter-mounted antitank systems concerns the OPFOR. Consequently, its doctrine calls for advancing forces to move as close behind the smokescreen as possible. The higher the smokescreen, the higher an enemy helicopter must go to observe troop movement behind the smokescreen, and the more vulnerable it is to ground-based air defense weapons. Depending on weather and terrain, some large-area smoke generators can produce screens up to several hundred meters high. There is considerable observation-free maneuver space behind a screen of this height. Conversely, smoke pots provide a screen 5 to 10 m high. This screen masks against ground observation but leaves the force vulnerable to helicopters “hugging the deck” and popping up to shoot.

The protection produced by camouflage smoke also interacts as a protective smoke. Just as smokescreens can degrade enemy night-vision sights, the protective smoke can shield friendly EO devices from potentially harmful laser radiation. This protective effect is greater with a darker smoke cloud because of the better absorption capability of that cloud. Protective smokescreens are also a good means of reducing the effects of thermal radiation from nuclear explosions. A protective smokescreen is useful in front of, around, or on top of friendly positions.

Decoy

A decoy smokescreen can deceive an enemy about the location of friendly forces and the probable direction of attack. If the enemy fires into the decoy smoke, the OPFOR can pinpoint the enemy firing systems and adjust its fire plan for the true attack. The site and location of decoy screens depend on the type of combat action, time available, terrain, and weather conditions. One use of decoy smoke is to screen simultaneously several possible crossing sites at a water obstacle. This makes it difficult for the enemy to determine which site(s) the OPFOR is actually using.

Area Smokescreens

Area smokescreens can cover wide surface areas occupied by fixed or semifixed facilities, or by mobile facilities or units that must remain in one location for extended periods. Screens set down on a broad frontage can also cover maneuver forces. The OPFOR uses area smokescreens to counter enemy precision weapons and deep attacks.

The means of generating area smokescreens can be either subordinate or supporting chemical units or the use of smoke pots, barrels, grenades, and VEESS. As the situation dictates, the objects screened by area smokescreens can include⎯

- Troop concentrations and assembly areas.

- CPs.

- Radar sites.

- Bridges and water obstacle-crossing sites.

The OPFOR can also screen air avenues of approach to such locations. It tries to eliminate reference points that could aid enemy aviation in targeting a screened location. To create an effective smokescreen against air attacks, the OPFOR must establish an effective air defense and CBRN warning communications network so that a smokescreen can be generated in time to degrade reconnaissance and targeting devices on incoming aircraft. Units using smoke must maintain reliable communications and continuous coordination with air defense early warning units and air defense firing positions.

The OPFOR follows the following basic principles for generating area smokescreens:

- Screening should include not only the protected object but also surrounding terrain or manmade features so as to deny the enemy reference points.

- The protected installation should not be in the center of the screen.

- The smoke release points must not disclose the outer contours of the screened object.

- Screening must be initiated early enough to allow the area to be blanketed by the time of the enemy attack.

- If possible, decoy smokescreens should be used.

- For larger objects (such as airfields and troop concentrations), the screen should be at least twice as large as the object.

- For smaller objects (such as depots, small crossing points, and radar sites), the screen should be at least 15 times as large as the object.

Depending on terrain, smoke release points are set up within a checkerboard pattern, in a ring (circle), or in a mix of the two patterns that covers the area to be screened.

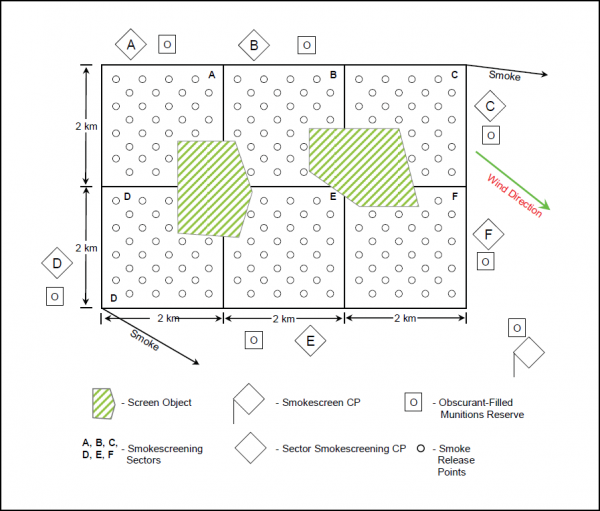

Checkerboard Area Smokescreen

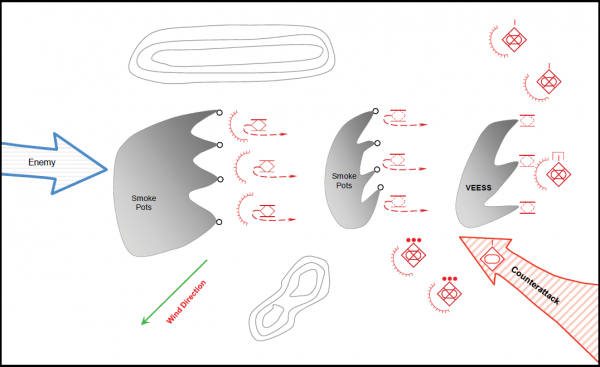

A checkerboard pattern is a rectangle that is divided into 4-km2 squares with smoke release points distributed evenly within each square (see figure 13-2). This pattern is useful if the terrain is contoured or covered with buildings, trees, or other obstructions that prevent the precise distribution of smoke points.

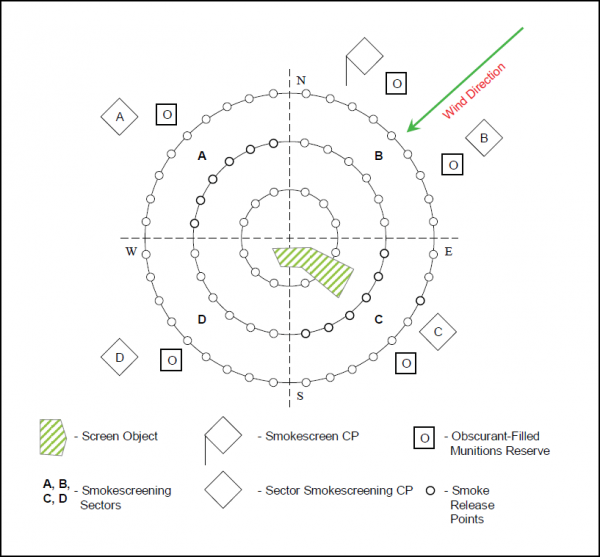

Ring Area Smokescreen

A circle or set of concentric rings of smoke release points works well on relatively flat, featureless terrain (see figure 13-3). Generally, the distance between the target and the first obscurant-generation ring is 100 to 250 m. The distance between smoke release points within each ring varies between 20 and 100 m, depending on the obscurant device being used and the meteorological conditions.

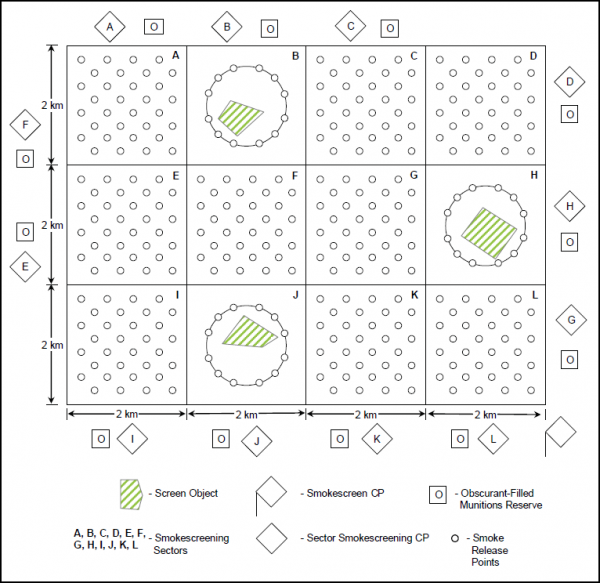

MIxed Area Smokescreen

The OPFOR uses checkerboard area smokescreens and ring area smokescreens together when objects 3 to 4 km apart must be screened simultaneously. The rings of smoke-generation lines are placed around each object to be screened, and these rings are placed within the squares of a checkerboard. See figure 13-4 for an example of a mixed area smokescreen.

Tactical Smokescreen Employment

The use of smoke is an important part of tactical C3D efforts. The OPFOR can use smokescreens to blind or deceive enemy forces and to conceal friendly forces from observation and targeting. Smoke can screen units near the battle lines, as well as those in support zones, from direct fire, reconnaissance, and air attack. It has applications in offense and defense, including tactical movement. Smoke is very effective in screening water obstacle crossings. It also has specific applications at night. Table 13-2 shows tactical options for employing smoke and other obscurants.

| Source | Placement | Uses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On Friendly | Between | On Enemy | Blinding | Camouflage | Decoy | Signaling | |

| Smoke Grenade | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Smoke Generator | X | X | X | X | |||

| Smoke Pot | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| VEESS | X | X | X | ||||

| Vehicle Dust | X | X | X | ||||

| Helicopter | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Mortar/Artillery Smoke | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Rocket | X | X | X | ||||

| Aerial Bomb | X | X | X | ||||

| Aircraft Spray | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Mortar/Artillery HE Dust | X | X | X | ||||

Offense

The OPFOR emphasizes the use of smoke during the offense to help reduce friendly battle losses. However, it understands that smoke may hinder its own C2, battlefield observation, and target engagement capabilities. In addition, the enemy may take advantage of OPFOR smokescreens to shield his own maneuvers or to carry out a surprise attack or counterattack. Thus, a smokescreen is successful when the OPFOR attackers are able to maintain their assigned axis and retain sight of the objective. To prevent the smoke from interfering with friendly maneuver, OPFOR commanders coordinate the planned location and duration of the smoke-generation lines or points with the scheme of maneuver.

Smoke pots, artillery, mortars, and aircraft are the primary means of smoke dissemination in the offense. Artillery and aircraft are used to spread screening smoke throughout the tactical depth of the enemy’s defense. They are also useful in screening the flanks of attacking units.

The OPFOR uses camouflage, blinding, and decoy smokescreens to conceal the direction and time of attack. The OPFOR can place smoke on enemy firing positions and OPs before and during an attack. Smoke has uses during various types of offensive action, which may be conducted against an enemy occupying defensive positions or an enemy on the move.

Enemy in Defensive Positions

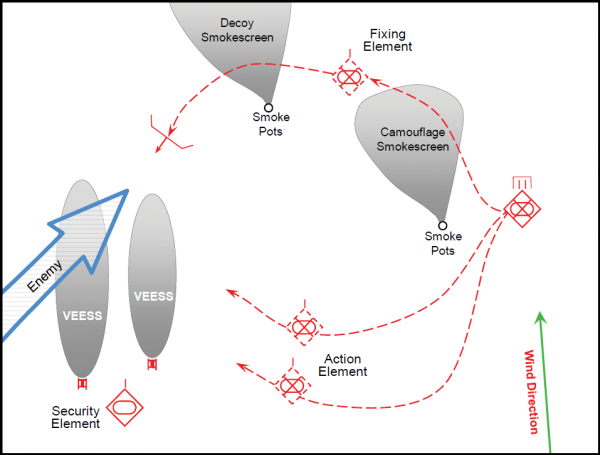

During the offense, a camouflage smokescreen is typically used to conceal combat formations that are advancing and maneuvering toward the enemy’s defensive positions. With a tail wind, the action and enabling forces or elements can generate enough smoke to adequately screen their front. Then they can advance behind the screen as it blows toward the enemy.

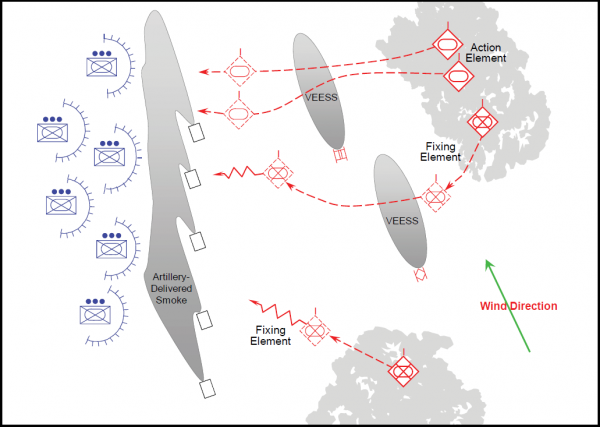

The example in figure 13-5 shows an independent mission detachment (IMD) with two mechanized infantry companies and two tank companies. This IMD is advancing from a wooded area in platoon formations with a flanking wind. In such conditions, the IMD may use its VEESS-equipped tanks and IFVs and smoke grenades. After turning on their VEESS, the tanks and IFVs advance toward the enemy’s defensive positions while firing on visible targets. Dismounted infantrymen equipped with smoke grenades follow on foot behind the extended line of tanks and IFVs. As gaps develop in the smokescreen, the infantrymen approach and throw smoke grenades. Infantrymen can also fire incendiary smoke charges from a variant of the encapsulated flamethrower out to a range of up to 1 km. In this example, artillery also delivers blinding smoke where the wind will carry it through the enemy defensive positions.

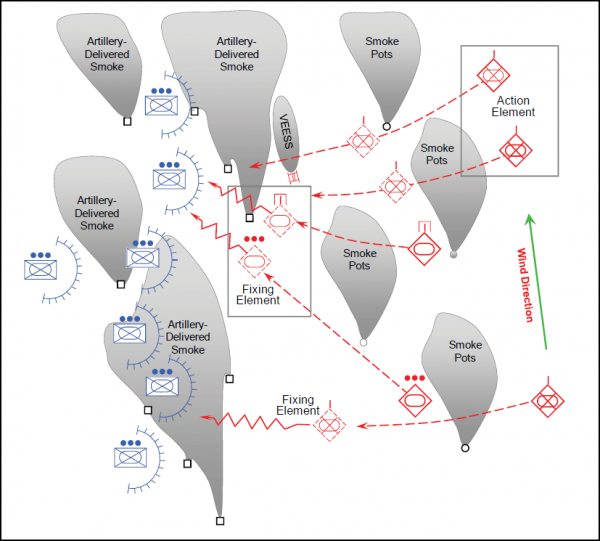

Figure 13-6 shows another example of smoke employment during an attack against an enemy in defensive positions. In this example, the commander has more opportunity to plan and prepare for a coordinated smokescreen than in the previous example. Again, a camouflage smokescreen is used to prevent observation of advancing fixing and action elements. As the advancing action element nears the rear of units of the fixing element already in contact with the enemy, the unit in contact may set up a camouflage smokescreen using smoke pots and VEESS of forward-deployed armored vehicles. In addition, artillery can deliver blinding smoke on enemy defensive positions while units of the action element negotiate minefields in front of them.

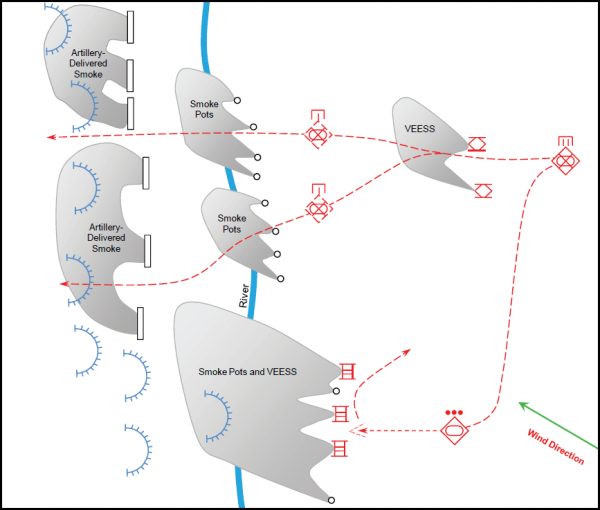

Enemy on the Move