Chapter 1: Strategic and Operational Framework

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.2 Opposing Force Tactics.

This chapter describes the State’s national security strategy and how the State designs campaigns and operations to achieve strategic goals outlined in that strategy. This provides the general framework within which the OPFOR plans and executes military actions at the tactical level, which are the focus of the remainder of this TC. See FM 7-100.1 for more detail on OPFOR operations.

Note. The State and its armed forces may act independently, as part of a multinational alliance or coalition, or as part of the Hybrid Threat (HT). When part of the HT, its regular forces will act in concert with irregular forces and/or criminal elements to achieve mutually benefitting effects. In such cases, the national-level strategy, operational designs, and courses of action of the State may coincide with those of the HT. (See TC 7-100 for HT strategy and operations.)

Contents

National-Level Organization

The State intends to achieve its strategic goals and objectives through the integrated use of four instruments of national power:

- Diplomatic-political.

- Informational.

- Economic.

- Military.

The four instruments are interrelated and complementary. A clear-cut line of demarcation between military, economic, and political matters does not exist. The informational instrument cuts across the other three. Thus, the State believes that its national security strategy must include all the instruments of national power, not just the military. Power is a combination of many elements, and the State can use them in varying combinations as components of its overall national security strategy.

Note. The term the State is simply a generic placeholder until trainers replace it. In specific U.S. Army training environments, the generic name of the State may give way to other (fictitious) country names. (See guidance in AR 350-2.)

National Command Authority

The National Command Authority (NCA) exercises overall control of the application of all instruments of national power in planning and carrying out the national security strategy. Thus, the NCA includes the cabinet ministers responsible for those instruments of power:

- The Minister of Foreign Affairs.

- The Minister of Public Information.

- The Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs.

- The Minister of the Interior.

- The Minister of Defense.

It may include other members selected by the State’s President, who chairs the NCA.

The President also appoints a Minister of National Security, who heads the Strategic Integration Department (SID) within the NCA. The SID is the overarching agency responsible for integrating all the instruments of national power under one cohesive national security strategy. The SID coordinates the plans and actions of all State ministries, but particularly those associated with the instruments of power. (See figure 1-1.)

Armed Forces

The NCA exercises command and control (C2) of the State’s armed forces (OPFOR) via the Supreme High Command (SHC). The SHC includes the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and a General Staff drawn from all the service components. (See figure 1-2 on page 1-3.) In peacetime, the MOD and General Staff operate closely but separately. The MOD is responsible for policy, acquisitions, and financing the armed forces. The General Staff promulgates policy and supervises the service components. Its functional directorates are responsible for key aspects of defense planning. During wartime, the MOD and General Staff merge to form the SHC, which functions as a unified headquarters.

The State organizes its armed forces into six service components:

- Army. The largest of the six services, although it relies on mobilization of reserve and militia forces to conduct sustained operations.

- Navy. Includes naval infantry.

- Air Force. Includes national-level Air Defense Forces.

- Strategic Forces. With long-range rockets and missiles.

- Special-Purpose Forces (SPF) Command. Includes SPF and commando units.

- Internal Security Forces. Subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime, but can be resubordinated to the SHC as a sixth service in time of war.

Administrative Force Structure

The OPFOR has an administrative force structure (AFS) that manages its military forces in peacetime. This AFS is the aggregate of various military headquarters, facilities, and installations designed to man, train, and equip the forces. In peacetime, forces are commonly grouped into corps, armies, or army groups for administrative purposes. An army group can consist of several armies, corps, or separate divisions and brigades. In some cases, forces may be grouped administratively under geographical commands designated as military regions or military districts. If the SHC elects to create more than one theater headquarters, it may allocate parts of the AFS to each of the theaters, normally along geographic lines. Normally, these administrative groupings differ from the OPFOR’s go-to-war (fighting) force structure. Other parts of the AFS consist of assets centrally controlled at the national level.

In wartime, the normal role of administrative commands is to serve as force providers during the creation of operational- and tactical-level fighting commands. Typically, an administrative command transfers control of its major fighting forces to one or more task-organized fighting commands. After doing so, the administrative headquarters, facility, or installation may continue to provide depot- and area support-level administrative, supply, and maintenance functions. A geographically based administrative command also provides a framework for the continuing mobilization of reserves to complement or supplement regular forces. In rare cases, an administrative command could function as a fighting command. (See FM 7-100.4 for the basic structures of OPFOR organizations in the AFS and guidance on how they can be task-organized in the fighting force structure.)

National Security Strategy

The national security strategy is the State’s vision for itself as a nation and the underlying rationale for building and employing its instruments of national power. It outlines how the State plans to use all its instruments of national power to achieve its strategic goals. Despite the term security, this strategy defines not just what the State wants to protect or defend, but what it wants to achieve.

National Strategic Goals

The NCA determines the State’s strategic goals. The State’s overall goals are to continually expand its influence within its region and possibly to enhance its position within the global community. These are the long-term aims of the State. Supporting the overall, long-term, strategic goals, there may be one or more specific goals, each based on a particular threat or opportunity.

Framework for Implementing National Security Strategy

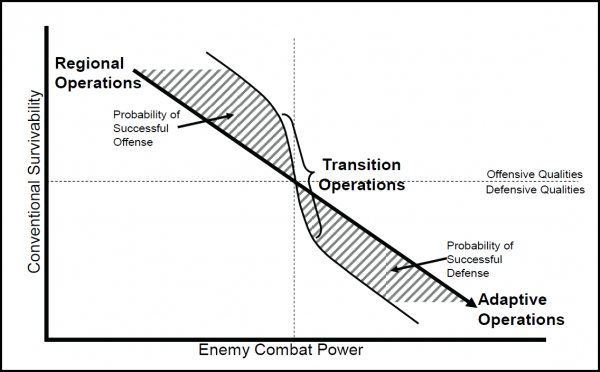

In pursuit of its national security strategy, the State is prepared to conduct four basic types of strategic-level courses of action (COA). (See figure 1-3.) Each COA involves the use of all four instruments of national power, but to different degrees and in different ways. The State gives the four types the following names:

- Strategic operations. A strategic-level COA that uses all instruments of power in peace and war to achieve the goals of the State’s national security strategy by attacking the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity.

- Regional operations. A strategic-level COA (including conventional, force-on-force military operations) against regional adversaries and internal threats.

- Transition operations. A strategic-level COA that bridges the gap between regional and adaptive operations and contains some elements of both. The State continues to pursue its regional goals while dealing with the development of outside intervention with the potential for overmatching the State’s capabilities.

- Adaptive operations. A strategic-level COA to preserve the State’s power and apply it in adaptive ways against opponents that may overmatch the State.

Although the State refers to them as “operations,” each of these COAs is actually a subcategory of strategy. Each of these types of “operations” is actually the aggregation of the effects of tactical, operational, and strategic actions. Those actions, in conjunction with the other three instruments of national power, contribute to the accomplishment of strategic goals. The type(s) of operations the State employs at a given time will depend on the types of threats and opportunities present and other conditions in the operational environment (OE).

Strategic operations are a continuous process not limited to wartime or preparation for war. Once war begins, they continue during regional, transition, and adaptive operations and complement those operations. The latter three types of strategic COAs are also operational designs (see Operational Designs, below). Each of those three occurs only during war and only under certain conditions.

Strategic Operations

What the State calls “strategic operations” is actually a universal strategic COA it would use to deal with all situations. Strategic operations can occur in peacetime and war—against all kinds of opponents, potential opponents, or neutral parties. The nature of strategic operations at any particular time corresponds to the conditions perceived by the NCA. Depending on the situation, the State may first try to achieve its ends through strategic operations alone, without having to resort to armed conflict. It may be able to achieve the desired goal through pressure applied by other-than-military instruments of power, perhaps with the mere threat of using its military power against a regional opponent. For additional information on strategic operations see FM 7-100.1.

Once war begins, the State will employ all means available against the enemy’s strategic centers of gravity:

- Diplomatic initiatives.

- Information warfare.

- Economic pressure.

- Terror attacks.

- State-sponsored insurgency.

- Direct action by SPF.

- Long-range precision fires.

- Even weapons of mass destruction against selected targets.

These efforts allow the enemy no sanctuary and often place noncombatants at risk.

Regional Operations

When nonmilitary means are not sufficient or expedient, the State may resort to armed conflict as a means of creating conditions that lead to the desired end state. However, strategic operations continue even if a particular regional threat or opportunity causes the State to undertake “regional operations” that include military means.

Prior to initiating armed conflict and throughout such conflict with its regional opponent, the State would continue to use strategic operations to preclude intervention by outside actors. Such actors could include other regional neighbors or an extraregional power that could overmatch the State’s forces. However, plans for regional operations always include branches and sequels for dealing with the possibility of intervention by an extraregional power.

At the military level, regional operations may be combined arms, joint, interagency, and/or multinational operations. They are conducted in the State’s region and, at least at the outset, against a regional opponent. The State’s doctrine, organization, capabilities, and national security strategy allow the OPFOR to deal with regional threats and opportunities primarily through offensive action.

Regionally focused operations typically involve “conventional” patterns of operation. However, the term conventional does not mean that the OPFOR will use only conventional forces and conventional weapons in such a conflict. Nor does it mean that the OPFOR will not use some adaptive approaches. Regional operations may also consist of military and paramilitary forces designed to destabilize the government of the opponent. An example of this might be one or more operational-strategic commands (OSCs) composed of SPF brigade(s), affiliated guerrilla brigade(s), information warfare battalion(s), and several different affiliated insurgent organizations. The headquarters of an OSC may not necessarily be colocated with its subordinate elements in the neighboring country, but may physically remain within the boundaries of the State.

Regional operations are not limited to only a single country. Similar operations to those in the example in the paragraph above may be conducted simultaneously in several different countries. A regional “neighbor” is not limited only to those countries sharing a physical international boundary with the State.

Transition Operations

When unable to limit the conflict to regional operations, the State is prepared to engage extraregional forces through a series of “transition and adaptive operations.” Usually, the State does not shift directly from regional to adaptive operations. The transition is incremental and does not occur at a single, easily identifiable point. If the State perceives that intervention is likely, transition operations may begin simultaneously with regional and strategic operations.

Transition operations allow the State to shift gradually to adaptive operations or back to regional operations. At some point, the State either seizes an opportunity to return to regional operations, or it reaches a point where it must complete the shift to adaptive operations. Even after shifting to adaptive operations, the State tries to set conditions for transitioning back to regional operations. Thus, a period of transition operations overlaps both regional and adaptive operations.

When an extraregional force starts to deploy into the region, the balance of power may begin to shift away from the State. Although the State may not yet be overmatched, it faces a developing threat it may not be able to handle with normal, “conventional” patterns of operation designed for regional conflict. Therefore, the State must begin to adapt its operations to the changing threat. Transition operations serve as a means for the State to retain the initiative and still pursue its overall strategic goals.

Adaptive Operations

Once an extraregional force intervenes with sufficient power, the full conventional design used in regionally focused operations may no longer be sufficient to deal with this threat. The State has developed its doctrine, organization, capabilities, and strategy with an eye toward dealing with both regional and extraregional opponents.

The OPFOR still has the same forces and technology that were available to it for regional operations. However, it must use them in creative and adaptive ways. It has already thought through how it will adapt to this new or changing threat in general terms. It has already developed appropriate branches and sequels to its basic strategic campaign plan (SCP) and does not have to rely on improvisation. During the course of combat, it will make further adaptations, based on experience and opportunity.

Even with the intervention of an advanced extraregional power, the State will not cede the initiative. It will employ military means so long as this does not either place the regime at risk or risk depriving it of sufficient force to pursue its regional goals after the extraregional intervention is over. The primary objectives are to—

- Preserve combat power.

- Degrade the enemy’s will and capability to fight.

- Gain time for aggressive strategic operations to succeed.

The State believes that adaptive operations can lead to several possible outcomes. If the results do not completely resolve the conflict in the State’s favor, they may at least allow the State to return to regional operations. Even a stalemate may be a victory for the State, as long as it preserves enough of its instruments of power to preserve the regime and lives to fight another day.

Strategic Campaign

To achieve one or more specific strategic goals, the NCA would develop and implement a specific national strategic campaign. Such a campaign is the aggregate of actions of all the State’s instruments of power to achieve a specific set of the State’s strategic goals. There would normally be a diplomatic- political campaign, an information campaign, and an economic campaign, as well as a military campaign. All of these must fit into a single, integrated national strategic campaign.

The campaign could include more than one specific strategic goal. For instance, any strategic campaign designed to deal with an insurgency would include contingencies for dealing with reactions from regional neighbors or an extraregional power that could adversely affect the State and its ability to achieve the selected goal. Likewise, any strategic campaign focused on a goal that involves the State’s invasion of a regional neighbor would have to take into consideration possible adverse actions by other regional neighbors, the possibility that insurgents might use this opportunity to take action against the State, and the distinct possibility that the original or expanded regional conflict might lead to extraregional intervention.

Figure 1-4 shows an example of a single strategic campaign that includes three strategic goals. (The map in this diagram is for illustrative purposes only and does not necessarily reflect the actual size, shape, or physical environment of the State or its neighbors.)

National Strategic Campaign Plan

The national SCP is the plan for integrating the actions of all instruments of national power to set conditions favorable for achieving the central goal(s) identified in the national security strategy. The MOD is only one of several State ministries that provide input and are then responsible for carrying out their respective parts of the consolidated national plan. State ministries responsible for each of the four instruments of power will develop their own campaign plans as part of the unified national SCP.

A national SCP defines the relationships among all State organizations, military and nonmilitary, for the purposes of executing that SCP. The SCP describes the intended integration, if any, of multinational forces in those instances where the State is acting as part of a coalition. It would also include the State’s interactions with irregular forces and/or criminal elements as part of the HT.

Military Strategic Campaign Plan

Within the context of the national strategic campaign, the MOD and General Staff develop and implement a military strategic campaign. During peacetime, the Operations Directorate of the General Staff is responsible for developing, staffing, promulgation, and continuing review of the military strategic campaign plan. It must ensure that the military plan would end in achieving military conditions that would fit with the conditions created by the diplomatic-political, informational, and economic portions of the national plan that are prepared by other State ministries. Therefore, the Operations Directorate assigns liaison officers to other important government ministries.

Although the State’s armed forces (OPFOR) may play a role in strategic operations, the focus of their planning and effort is on the military aspects of regional, transition, and adaptive operations. A military strategic campaign may include several combined arms, joint, and/or interagency operations. If the State succeeds in forming a regional alliance or coalition, these operations may also be multinational.

The General Staff acts as the executive agency for the NCA. All military forces report through it to the NCA. The Chief of the General Staff (CGS), with NCA approval, defines the theater in which the armed forces will conduct the military campaign and its subordinate operations. He determines the task organization of forces to accomplish the operational-level missions that support the overall campaign plan. He also determines whether it will be necessary to form more than one theater headquarters. For most campaigns, there will be only one theater, and the CGS will serve as theater commander, thus eliminating one echelon of command at the strategic level.

In wartime, the MOD and the General Staff combine to form the SHC, under the command of the CGS. The Operations Directorate continues to review the military SCP and modify it or develop new plans based on guidance from the CGS. It generates options and contingency plans for various situations that may arise. Once the CGS approves a particular plan for a particular strategic goal, he issues it to the appropriate operational-level commanders.

The military SCP assigns forces to operational-level commands and designates areas of responsibility (AORs) for those commands. Each command identified in the SCP prepares an operation plan that supports the execution of its role in that SCP.

From the General Staff down through the operational and tactical levels, the staff of each military headquarters has an operations directorate or section that is responsible for planning. The plan at each level specifies the AOR and task organization of forces allocated to that level of command, in order to accomplish the mission assigned by a higher headquarters. Once the commander at a particular level approves the plan, he issues it to the subordinate commanders who will execute it. Figure 1-5 illustrates the framework for planning from the national level down through military channels to the operational and tactical levels.

Operational-Level Organization

In peacetime, tactical-level commands belong to parent organizations in the AFS. In wartime, they typically serve as part of a field group (FG) or an OSC. In rare cases, they might also fight as part of their original parent units from the AFS.

Field Group

An FG is the largest operational-level organization, since it has one or more smaller operational-level commands subordinate to it. FGs are always joint and interagency organizations and are often multinational. However, this level of command may or may not be necessary in a particular SCP. The General Staff does not normally form standing FG headquarters, but may organize one or more during full mobilization, if necessary. An FG may be organized when the span of control at theater level exceeds four or five subordinate commands. This can facilitate the theater commander’s remaining focused on the theater-strategic level of war and enable him to coordinate effectively the joint forces allocated for his use.

FGs are typically formed for one or more of the following reasons:

- An SCP may require a large number of OSCs and/or operational-level commands from the AFS. When the number of major military efforts in a theater exceeds the theater commander’s desired or achievable span of control, he may form one or more FGs.

- In the rare cases when multiple operational-level commands from the AFS become fighting commands, they could come under the command of an FG headquarters.

- Due to modifications to the SCP, a standing operational-level headquarters that was originally designated as an OSC headquarters may receive one or more additional major operational-level commands from the AFS as fighting commands. Then the OSC headquarters would evolve into an FG headquarters.

In the first two cases, a standing FG staff would be formed and identified as having control over two or more OSCs (or operational-level headquarters from the AFS) as part of the same SCP. In the third case, the original OSC headquarters would be redesignated as an FG headquarters. In any case, the FG command group and staff would be structured in the same manner as those of an OSC.

Operational-Strategic Command

The OPFOR’s primary operational organization is the OSC. (See FM 7-100.1 for more detail.) Once the General Staff writes a particular SCP, it forms one or more standing OSC headquarters. Each OSC headquarters is capable of controlling whatever combined arms, joint, interagency, or multinational operations are necessary to execute that OSC’s part of the SCP. However, the OSC headquarters does not have forces permanently assigned to it.

When the NCA decides to execute a particular SCP, each OSC participating in that plan receives appropriate units from the AFS, as well as interagency and/or multinational forces. The allocation of organizations to an OSC depends on what is available in the State’s AFS and the requirements of other OSCs. Forces subordinated to an OSC may continue to depend on the AFS for support.

If a particular OSC has contingency plans for participating in more than one SCP, it could receive a different set of forces under each plan. In each case, the forces would be task-organized according to its mission requirements in the given plan. Thus, each OSC consists of those division-, brigade-, and battalion-size organizations allocated to it by the SCP currently in effect. These forces also may be allocated to the OSC for the purpose of training for a particular SCP. When an OSC is neither executing tasks as part of an SCP nor conducting exercises with its identified subordinate forces, it exists as a planning headquarters.

Operational Designs

Of the four types of strategic COA described above, regional, transition, and adaptive operations are also operational designs. While the State and the OPFOR as a whole are in the condition of regional, transition, or adaptive operations, an operational- or tactical-level commander will still receive a mission statement in plans and orders from his higher authority stating the purpose of his actions. To accomplish that purpose and mission, he will use—

- As much as he can of the conventional patterns of operation that were available to him during regional operations.

- As much as he has to of the more adaptive-type approaches dictated by the presence of an extraregional force.

Figure 1-6 illustrates the basic conceptual framework for the three operational designs.

Regional Operations

Against opponents from within its region, the OPFOR may conduct “regional operations” with a relatively high probability of success in primarily offensive actions. OPFOR offensive operations are characterized by using all available means to saturate the OE with actions designed to disaggregate an opponent’s capability, capacity, and will to resist. These actions will not be limited to attacks on military and security forces, but will affect the entire OE. The opponent will be in a fight for survival across many of the variables of the OE: political, military, economic, social, information, and infrastructure.

The OPFOR may possess an overmatch in some or all elements of combat power against regional opponents. It is able to employ that power in an operational design focused on offensive action. A weaker regional neighbor may not actually represent a threat, but rather an opportunity that the OPFOR can exploit. To seize territory or otherwise expand its influence in the region, the OPFOR must destroy a regional enemy’s will and capability to continue the fight.

During regional operations, the OPFOR relies on the State’s continuing strategic operations (see above) to preclude or control outside intervention. It tries to keep foreign perceptions of its actions during a regional conflict below the threshold that will invite intervention by other regional actors or extraregional forces. The OPFOR wants to achieve its objectives in the regional conflict, but has to be careful how it does so. It works to prevent development of international consensus for intervention and to create doubt among possible participants. Still, at the very outset of regional operations, it lays plans and positions forces to conduct access-limitation operations in the event of outside intervention.

Although the OPFOR would prefer to achieve its objectives through regional operations, it has the flexibility to change and adapt if required. Since the OPFOR assumes the possibility of extraregional intervention, its operation plans will already contain thorough plans for transition operations, as well as adaptive operations, if necessary.

Transition Operations

Transition operations serve as a pivotal point between regional and adaptive operations. The transition may go in either direction. The fact that the OPFOR begins transition operations does not necessarily mean that it must complete the transition from regional to adaptive operations (or vice versa).

As conditions allow or dictate, the “transition” could end with the OPFOR conducting the same type of operations as before the shift to transition operations.

The OPFOR conducts transition operations when other regional and/or extraregional forces threaten its ability to continue regional operations in a conventional design against the original regional enemy. At the point of shifting to transition operations, the OPFOR may still have the ability to exert its combat power against an overmatched regional enemy. Indeed, it may have already defeated its original adversary. However, its successful actions in regional operations have prompted either other regional actors or an extraregional actor to contemplate intervention. The OPFOR will use all means necessary to preclude or defeat intervention.

Even extraregional forces may be vulnerable to “conventional” operations during the time they require to build combat power and create support at home for their intervention. Against an extraregional force that either could not fully deploy or has been successfully separated into isolated elements, the OPFOR may still be able to use some of the more conventional patterns of operation.

As the OPFOR begins transition operations, its immediate goal is preservation of its combat power while seeking to set conditions that will allow it to transition back to regional operations. Transition operations feature a mixture of offensive and defensive actions that help the OPFOR control the tempo while changing the nature of conflict to something for which the intervening force is unprepared. Transition operations can also buy time for the State’s strategic operations to succeed.

There are two possible outcomes to transition operations:

- The extraregional force suffers sufficient losses or for other reasons must withdraw from the region. In this case, the OPFOR’s operations may begin to transition back to regional operations, again becoming primarily offensive.

- The extraregional force is not compelled to withdraw and continues to build up power in the region. In this case, the OPFOR’s transition operations may begin to gravitate in the other direction, toward adaptive operations.

Adaptive Operations

At some point, an extraregional force may intervene with sufficient power to overmatch the OPFOR at least in certain areas. When that occurs, the OPFOR has to adapt its patterns of operation to deal with this threat. The OPFOR will seek to conduct adaptive operations in circumstances and terrain that provide opportunities to optimize its own capabilities and degrade those of the enemy. It will employ a force that is optimized for the terrain or for a specific mission. For example, it will use its antitank capability, tied to obstacles and complex terrain, inside a defensive structure designed to absorb the enemy’s momentum and fracture his organizational framework.

At least at the tactical and operational levels, the types of adaptive actions and methods that characterize adaptive operations can also serve the OPFOR well in regional or transition operations. However, the OPFOR will conduct such adaptive actions more frequently and on a larger scale during adaptive operations against a fully-deployed extraregional force. During the course of operations, the OPFOR will make further adaptations, based on what works or does not work against a particular opponent.

Types of Offensive and Defensive Action

The types of offensive action in OPFOR doctrine are both tactical methods and guides to the design of operational COAs. An OSC offensive operation plan may include subordinate units that are executing different offensive and defensive COAs within the overall offensive mission framework. The OPFOR recognizes three basic types of offensive action at OSC level: attack, limited-objective attack, and strike. (See chapter 3 for discussion of the first two types of action at the tactical group, division, and brigade level.) A strike is an offensive action that rapidly destroys a key enemy organization through a synergistic combination of massed precision fires and maneuver (see FM 7-100.1 for more detail).

The OPFOR’s types of defensive action also are both tactical methods and guides to the design of operational COAs. The two basic types are maneuver defense and area defense. An OSC defensive operation plan may include subordinate units that are executing various combinations of maneuver and area defenses, along with some offensive COAs, within the overall defensive mission framework. (See chapter 4 for discussion of the same types of defensive action at the tactical group, division, and brigade level.)

Systems Warfare

The OPFOR defines a system as a set of different elements so connected or related as to perform a unique function not performable by the elements or components alone. The essential ingredients of a system include—

- The components.

- The synergy among components and other systems.

- Some type of functional boundary separating it from other systems.

Therefore, a “system of systems” is a set of different systems so connected or related as to produce results unachievable by the individual systems alone. The OPFOR views the OE, the battlefield, the State’s own instruments of power, and an opponent’s instruments of power as a collection of complex, dynamic, and integrated systems composed of subsystems and components.

Principle

The primary principle of systems warfare is the identification and isolation of the critical subsystems or components that give the opponent the capability and cohesion to achieve his aims. While the aggregation of these subsystems or components is what makes the overall system work, the interdependence of these subsystems is also a potential vulnerability. The focus is on disaggregating the system by attacking critical subsystems in a way that will degrade or destroy the use, effectiveness, or importance of the overall system. Systems warfare has applicability or impact at all three levels of warfare.

Application at the Strategic Level

At the strategic level, the instruments of national power and their application are the focus of analysis. National power is a system of systems in which the instruments of national power work together to create a synergistic effect. Each instrument of power (diplomatic-political, informational, economic, and military) is also a collection of complex and interrelated systems.

The State clearly understands how to analyze and locate the critical components of its own instruments of power. It will aggressively aim to protect its own systems from attack or vulnerabilities. It also understands that an adversary’s instruments of power are similar to the State’s. Thus, at the strategic level, the State can use the OPFOR and its other instruments of power to counter or target the systems and subsystems that make up an opponent’s instruments of power. The primary purpose is to subdue, control, or change the opponent’s behavior.

If an opponent’s strength lies in his military power, the State and the OPFOR can attack the other instruments of power as a means of disaggregating or disrupting the enemy’s system of national power. Thus, it is possible to render the overall system ineffective without necessarily having to defeat the opponent militarily.

Application at the Operational Level

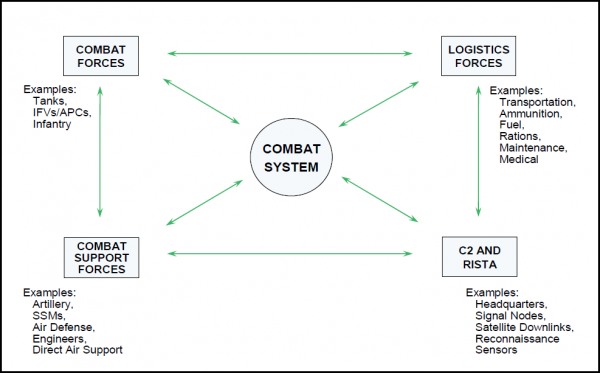

At the operational level, the application of systems warfare pertains only to the use of armed forces to achieve a result. Therefore, the “system of systems” in question at this level is the combat system of the OPFOR and/or the enemy.

Combat System

A combat system (see figure 1-7) is the “system of systems” that results from the synergistic combination of four basic subsystems that are integrated to achieve a military function. The subsystems are as follows:

- Combat forces—such as main battle tanks, infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) and/or armored personnel carriers (APCs), or infantry.

- Combat support forces—such as artillery, surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs), air defense, engineers, and direct air support.

- Logistics forces—such as transportation, ammunition, fuel, rations, maintenance, and medical.

- C2 and reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance and target acquisition (RISTA)—such as headquarters, signal nodes, satellite downlink sites, and reconnaissance sensors.

The combat system is characterized by interaction and interdependence among its subsystems. Therefore, the OPFOR will seek to identify key subsystems of an enemy combat system and target them and destroy them individually. Against a technologically superior extraregional force, the OPFOR will often use any or all subcomponents of its own combat system to attack the most vulnerable parts of the enemy’s combat system rather than the enemy’s strengths. For example, attacking the enemy’s logistics, C2, and RISTA can undermine the overall effectiveness of the enemy’s combat system without having to directly engage his superior combat and combat support forces. Aside from the physical effect, the removal of one or more key subsystems can have a devastating psychological effect, particularly if it occurs in a short span of time.

Planning and Execution

The systems warfare approach to combat is a means to assist the commander in the decisionmaking process and the planning and execution of his mission. The OPFOR believes that a qualitatively and/or quantitatively weaker force can defeat a superior foe, if the lesser force can dictate the terms of combat. It believes that the systems warfare approach allows it to move away from the traditional attrition-based approach to combat. It is no longer necessary to match an opponent system-for-system or capability-for-capability. Commanders and staffs will locate the critical component(s) of the enemy combat system, patterns of interaction, and opportunities to exploit this connectivity. The OPFOR will seek to disaggregate enemy combat power by destroying or neutralizing single points of failure in the enemy’s combat system. Systems warfare has applications in both offensive and defensive contexts.

The essential step after the identification of the critical subsystems and components of a combat system is the destruction or degradation of the synergy of the system. This may take one of three forms—

- Total destruction of a subsystem or component.

- Degradation of the synergy of components.

- The simple denial of access to critical links between systems or components.

The destruction of a critical component or link can achieve one or more of the following:

- Create windows of opportunity that can be exploited.

- Set the conditions for offensive action.

- Support a concept of operation that calls for exhausting the enemy on the battlefield.

Once the OPFOR has identified and isolated a critical element of the enemy combat system that is vulnerable to attack, it will select the appropriate method of attack.

Today’s state-of-the-art combat and combat support systems are impressive in their ability to deliver precise attacks at long standoff distances. However, the growing reliance of some extraregional forces on these systems offers opportunity. For example, attacking critical ground-based C2 and RISTA nodes or logistics systems and lines of communication (LOCs) may have a very large payoff for relatively low investment and low risk. Modern logistics systems assume secure LOCs and voice or digital communications. These characteristics make such systems vulnerable. Therefore, the OPFOR can greatly reduce a military force’s combat power by attacking a logistics system that depends on “just-in-time delivery.”

For the operational commander, the systems warfare approach to combat is not an end in itself. It is a key component in his planning and sequencing of tactical battles and engagements aimed toward achieving assigned strategic goals. Systems warfare supports his concept; it is not the concept. The ultimate aim is to destroy the enemy’s will and ability to fight.

Application at the Tactical Level

It is at the tactical level that systems warfare is executed in attacking the enemy’s combat system. While the tactical commander may use systems warfare in the smaller sense to accomplish assigned missions, his attack on systems normally will be in response to missions assigned him by the operational commander.

Application Across all Types of Strategic-Level Actions

Systems warfare is applicable against all types of opponents in all strategic-level COAs. In regional operations, the OPFOR will seek to render a regional opponent’s systems ineffective to support his overall concept of operation. However, this approach is especially conducive to the conduct of transition and adaptive operations. The very nature of this approach lends itself to adaptive and creative options against an adversary’s technological overmatch.

Relationship to the C2 Process

The systems warfare approach to combat is an important part of OPFOR planning. It serves as a means to analyze the OPFOR’s own combat system and how it can use the combined effects of this system to degrade the enemy’s combat system. The OPFOR believes that the approach allows its decisionmakers to be anticipatory rather than reactive.

The Role of Paramilitary Forces in Operations

Paramilitary forces are those organizations that are distinct from the regular armed forces but resemble them in organization, equipment, training, or purpose. Basically, any organization that accomplishes its purpose, even partially, through the force of arms could be considered a paramilitary organization. These organizations can be part of a government infrastructure or operate outside of any government or any institutionalized controlling authority.

The OPFOR views these organizations as assets that can be used to its advantage in time of war. Within its own structure, the OPFOR has formally established this concept by assigning the Internal Security Forces, part of the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime, to the SHC during wartime. Additionally, the OPFOR cultivates relationships with and covertly supports nongovernment paramilitary organizations to achieve common goals while at peace and to have a high degree of influence on them when at war.

The primary paramilitary organizations are the Internal Security Forces, irregular forces, and criminal organizations. The degree of control the OPFOR has over these organizations varies from absolute, in the case of the Internal Security Forces, to tenuous when dealing with irregular forces and criminal organizations. In the case of those organizations not formally tied to the OPFOR structure, control can be enhanced through the exploitation of common interests and ensuring that these organizations see personal gain in supporting OPFOR goals. Common interests may result in the State’s regular military forces acting as part of the HT, which also includes irregular forces and/or criminal elements.

The OPFOR views the creative use of these organizations as a means of providing depth and continuity to its operations. A single attack by an irregular force will not in itself win the war. However, the use of paramilitary organizations to carry out a large number of planned actions, in support of strategy and operations, can play an important part in assisting the OPFOR in achieving its goals. These actions, taken in conjunction with other adaptive actions, can also supplement a capability degraded due to enemy superiority.