Chapter 2: Command and Control (TC 7-100.2)

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.2 Opposing Force Tactics.

This chapter focuses on tactical command and control (C2). It explains how the OPFOR expects to direct the forces and actions described in other chapters of this TC. Most important, it shows how OPFOR commanders and staffs think and work. In modern war, the overriding need for speedy decisions to seize fleeting opportunities drastically reduces the time available for decisionmaking and for issuing and implementing orders. Moreover, the tactical situation is subject to sudden and radical changes, and the results of combat are more likely to be decisive than in the past. OPFOR C2 participants, processes, and systems are designed to operate effectively and efficiently in this environment.

Contents

- 1 Concept and Principles

- 2 Command and Support Relationships

- 3 Tactical-Level Organizations

- 4 Organizing the Tactical Battlefield

- 5 Functional Organization of Forces and Elements

- 6 Headquarters, Command, and Staff

- 7 Command Posts

- 8 Command and Control Systems

Concept and Principles

The OPFOR defines command and control as the actions of commanders, command groups, and staffs of military headquarters to maintain continual combat readiness and combat efficiency of forces, to plan and prepare for combat operations, and to provide leadership and direction during the execution of assigned missions. It views the C2 process as the means for assuring both command (establishing the aim) and control (sustaining the aim). The OPFOR’s tactical C2 concept is based on the following key principles:

Mission Tactics

OPFOR tactical units focus on the purpose of their tactical missions. They continue to act on that purpose even when the details of an original plan have become irrelevant through enemy action or unforeseen events.

Flexibility Through Battle Drill

True flexibility comes from soldiers in tactical units understanding basic battlefield functions to such a degree that they are second nature. Battle drills are not viewed as a restrictive methodology. Only when common battlefield functions can be performed rapidly without further guidance or orders do tactical commanders achieve the flexibility to modify the plan on the move.

Accounting for Mission Dynamics

The OPFOR recognizes that enemy action and battlefield conditions may make the originally selected mission irrelevant and require an entirely new mission be acted upon without an intermediate planning session. An example would be an OPFOR fixing force that finds itself the target of an enemy fixing action. To continue solely as a fixing force would actually assist the enemy in achieving his mission. In this case, the OPFOR unit might choose to change its task organization on the move and allocate a part of the fixing force to the exploitation force and use a smaller amount of combat power to keep the enemy fixing force from being able to influence the fight. OPFOR tactical headquarters constantly evaluate the situation to determine if the mission being executed is still relevant and, if not, to advise the commander on how best to shift to a relevant course of action. Each situation requires the commander at each level of command to act flexibly, exercising his judgment as to what best meets and sustains the aim of his superior.

Command and Support Relationships

OPFOR units are organized using four command and support relationships, summarized in table 2-1 and described in the following paragraphs. These relationships may shift during the course of an operation in order to best align the force with the tasks required. The general category of subordinate units includes both constituent and dedicated relationships; it can also include interagency and multinational (allied) subordinates.

| Relationship | Commanded by | Logistics from | Positioned by | Priorities from |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constituent | Gaining | Gaining | Gaining | Gaining |

| Dedicated | Gaining | Parent | Gaining | Gaining |

| Supporting | Parent | Parent | Supported | Supported |

| Affiliated | Self | Self or "Parent" | Self | Mutual Agreement |

Constituent

Constituent units are those forces assigned directly to a unit and forming an integral part of it. They may be organic to the table of organization and equipment (TOE) of the administrative force structure forming the basis of a given unit, assigned at the time the unit was created, or attached to it after its formation.

Dedicated

Dedicated is a command relationship identical to constituent with the exception that a dedicated unit still receives logistics support from a parent headquarters of similar type. An example of a dedicated unit would be the case where a specialized unit, such as an attack helicopter company, is allocated to a brigade tactical group (BTG). The base brigade does not possess the technical experts or repair facilities for the aviation unit’s equipment. However, the dedicated relationship permits the company to execute missions exclusively for the BTG while still receiving its logistics support from its parent organization. In OPFOR plans and orders, the dedicated command and support relationship is indicated by (DED) next to a unit title or symbol.

Supporting

Supporting units continue to be commanded by and receive their logistics from their parent headquarters, but are positioned and given mission priorities by their supported headquarters. This relationship permits supported units the freedom to establish priorities and position supporting units while allowing higher headquarters to rapidly shift support in dynamic situations. An example of a supporting unit would be a multiple rocket launcher battalion supporting a BTG for a particular phase of an operation but ready to rapidly transition to a different support relationship when the BTG becomes the division tactical group (DTG) reserve in a later phase. The supporting unit does not necessarily have to be within the supported unit’s area of responsibility (AOR). In OPFOR plans and orders, the supporting command and support relationship is indicated by (SPT) next to a unit title or symbol.

Affiliated

Affiliated organizations are those operating in a unit’s AOR that the unit may be able to sufficiently influence to act in concert with it for a limited time. No “command relationship” exists between an affiliated organization and the unit in whose AOR it operates. Affiliated organizations are typically nonmilitary or paramilitary groups such as criminal cartels or insurgent organizations. In some cases, affiliated forces may receive support from the DTG or BTG as part of the agreement under which they cooperate. Although there will typically be no formal indication of this relationship in OPFOR plans and orders, in rare cases (AFL) is used next to unit titles or symbols.

Note. In organization charts, the affiliated status is reflected by a dashed (rather than solid) line connecting the affiliated force to the unit with which it is affiliated (see the examples in figures 2-1 and 2-2). This is not to be confused with dashed boxes, which indicate additional units that may or may not be present.

Tactical-Level Organizations

OPFOR tactical organizations fight battles and engagements. They execute the combat actions described in the remainder of this TC.

In the OPFOR’s administrative force structure (AFS), the largest tactical-level organizations are divisions and brigades. In peacetime, they are often subordinate to a larger, operational-level administrative command. However, a service of the Armed Forces might also maintain some separate single-service tactical-level commands (divisions, brigades, or battalions) directly under the control of their service headquarters. (See FM 7-100.4.) For example, major tactical-level commands of the Air Force, Navy, Strategic Forces, and the Special-Purpose Forces (SPF) Command often remain under the direct control of their respective service component headquarters. The Army component headquarters may retain centralized control of certain elite elements of the ground forces, including airborne units and Army SPF. This permits flexibility in the employment of these relatively scarce assets in response to national- level requirements.

For these tactical-level organizations (division and below), the organizational directories of FM 7-100.4 contain standard “TOE” structures of the AFS. However, these administrative groupings normally differ from the OPFOR’s go-to-war (fighting) force structure. (See FM 7-100.4 on task- organizing.)

Divisions

In the OPFOR’s AFS, the largest tactical formation is the division. Divisions are designed to be able to⎯

- Serve as the basis for forming a DTG, if necessary. (See discussion of Tactical Groups, below.)

- With or without becoming a DTG, fight as part of an operational-strategic command (OSC) or an organization from the AFS (such as army or military region) or as a separate unit in a field group (FG).

- Sustain independent combat operations over a period of several days.

- Integrate interagency forces up to brigade or group size.

- Execute all of the actions discussed in this TC

Integrated Fires Command

The integrated fires command (IFC) is a combination of a standing C2 structure and task- organizing of constituent and dedicated fire support units. Division or DTG and above have IFCs. Brigades, BTGs, and below do not. All division-level and above OPFOR organizations possess an IFC C2 structure-staff, command post (CP), communications and intelligence architecture, and automated fire control system. The IFC exercises C2 of all constituent and dedicated fire support assets retained by its level of command. This includes army aviation, artillery, and missile units. It also exercises C2 over all reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) assets allocated to it. (See chapter 9 for more detail on the IFC.)

Note. Based on mission requirements, the division or DTG (or above) commander may also place maneuver forces under the command of the IFC commander. One possibility would be for the IFC CP to command the disruption force, the exploitation force, or any other functional force whose actions must be closely coordinated with fires delivered by the IFC.

Integrated Support Command

The integrated support command (ISC) is the aggregate of combat service support units (and perhaps some combat support units) organic to a division and additional assets allocated from the AFS to a DTG. It contains such units that the division or DTG does not suballocate to lower levels of command in a constituent or dedicated relationship. The division or DTG further allocates part of its ISC units as an integrated support group (ISG) to support its IFC, and the remainder supports the rest of the division or DTG, as a second ISG.

For organizational efficiency, combat service support units may be grouped in this ISC and its ISGs, although they may support only one of the major units of the division or DTG or its IFC. Sometimes, an ISC or ISG might also include units performing combat support tasks (such as chemical warfare, engineer, or law enforcement) that support the division or DTG and its IFC. (See chapter 14 for more detail on the ISC and ISG.)

Maneuver Brigades

The OPFOR’s basic combined arms unit is the maneuver brigade. In the AFS, maneuver brigades are typically constituent to divisions, in which case the OPFOR refers to them as divisional brigades. However, some are organized as separate brigades, designed to have greater ability to accomplish independent missions without further allocation of forces from higher-level tactical headquarters. In OPFOR plans and orders, the status of separate brigades may be indicated by (Sep) next to a unit title or symbol. Similarly, a brigade that is part of a division may be marked as (Div) in order to distinguish it from a separate brigade.

Maneuver brigades are designed to be able to⎯

- Serve as the basis for forming a BTG, if necessary.

- Fight as part of a division or DTG.

- Fight as a separate unit in an OSC, an organization from the AFS (such as army, corps, or military district), or an FG.

- Sustain independent combat operations over a period of 1 to 3 days.

- Integrate interagency forces up to battalion size.

- Execute all of the actions discussed in this TC.

Tactical Groups

A tactical group is a task-organized division or brigade that has received an allocation of additional land forces in order to accomplish its mission. These additional forces may come from within the Ministry of Defense, from the Ministry of the Interior, or from affiliated forces. Typically, these assets are initially allocated to an OSC or FG, which further allocates them to its tactical subordinates. The purpose of a tactical group is to ensure unity of command for all land forces in a given AOR. Tactical groups formed from divisions are division tactical groups (DTGs) and those from brigades are brigade tactical groups (BTGs). A DTG may fight as part of an OSC or as a separate unit in an FG. A BTG may fight as part of a division or DTG or as a separate unit in an OSC or FG. Figures 2-1 and 2-2 give examples of the types of units that could comprise possible DTG and BTG organizations.

In addition to augmentation received from a higher command, a DTG or BTG normally retains the assets that were originally subordinate to the division or brigade that served as the basis for the tactical group. However, it is also possible that the higher command could use units from one division or brigade as part of a tactical group that is based on another division or brigade.

Note. Any division or brigade receiving additional assets from a higher command becomes a DTG or BTG.

The division that serves as the basis for a DTG may have some of its brigades task-organized as BTGs. However, just the fact that a division becomes a DTG does not necessarily mean that it forms BTGs. A DTG could augment all of its brigades, or one or two brigades, or none of them as BTGs. A division could augment one or more brigades into BTGs, using the division’s own constituent assets, without becoming a DTG. If a division receives additional assets and uses them all to create one or more BTGs, it is still designated as a DTG. Within a DTG or BTG, some battalions and companies may become task-organized as detachments, while others retain their original structures. (See discussion of Detachments, below.)

Note. Unit symbols for all OPFOR units use the diamond-shaped frame. All OPFOR task organizations use the “task force” symbol placed over the “echelon” (unit size) modifier above the diamond frame. When there is a color capability, there are two options for use of red: all parts of the symbol that would otherwise be black can use red, or the diamond can have red fill color with the frame and other parts of the symbol in black. (See figures 2-3 through 2-5 and also figures 2-10 through 2-14 on pages 2-9 through 2-11 for examples.)

Unit symbols for tactical groups show the unit type and size of the “base” unit (division or brigade) around which the task organization was formed and whose headquarters serves as the headquarters for the tactical group. Figures 2-3 through 2-5 show examples of unit symbols for various types of OPFOR tactical groups.

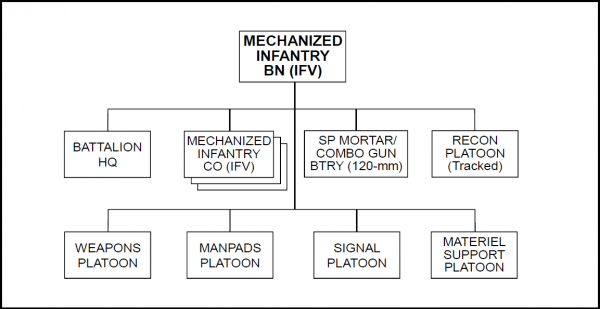

Battalions

In the OPFOR’s force structure, the basic unit of action is the battalion. (See figure 2-6.) Battalions are designed to be able to⎯

- Serve as the basis for forming a battalion-size detachment (BDET), if necessary. (See discussion of Detachments below.)

- Fight as part of a brigade, BTG, division, or DTG.

- Execute basic combat missions as part of a larger tactical force.

- Plan for operations expected to occur 6 to 24 hours in the future.

- Execute all of the tactical actions discussed in this TC.

Companies

In the OPFOR’s force structure, the largest unit without a staff is the company. In fire support units, this level of command is commonly called a battery. (See figure 2-7.) Companies are designed to be able to⎯

- Serve as the basis for forming a company-size detachment (CDET), if necessary. (See discussion of Detachments below.)

- Fight as part of a battalion, BDET, brigade, BTG, division, or DTG.

- Execute tactical tasks. (A company will not normally be asked to perform two or more tactical tasks simultaneously.)

Detachments

A detachment is a battalion or company designated to perform a specific mission and allocated the forces necessary to do so. (See figures 2-8 and 2-9.) Detachments are the smallest combined arms formations and are, by definition, task-organized. To further differentiate, detachments built from battalions can be termed battalion-size detachments (BDETs), and those formed from companies can be termed company-size detachments (CDETs). The forces allocated to a detachment suit the mission expected of it. They may include⎯

- Artillery or mortar units.

- Air defense units.

- Engineer units (with obstacle, survivability, or mobility assets).

- Heavy weapons units (including heavy machineguns, automatic grenade launchers, and antitank guided missiles).

- Units with specialty equipment such as flame weapons, specialized reconnaissance assets, or helicopters.

- Interagency forces up to company size for BDETs, or platoon size for CDETs.

- Chemical defense, antitank, medical, logistics, signal, and electronic warfare units.

BDETs can accept dedicated and supporting SPF, aviation (combat helicopter, transport helicopter), and unmanned aerial vehicle units.

The basic type of OPFOR detachment—whether formed from a battalion or a company—is the independent mission detachment (IMD). IMDs are formed to execute missions that are separated in space and/or time from those being conducted by the remainder of the forming unit. IMDs can be used for a variety of missions, some of which are listed here as examples:

- Seizing key terrain.

- Linking up with airborne or heliborne forces.

- Conducting tactical movement on secondary axes.

- Pursuing or enveloping an enemy force.

- Conducting a raid or ambush.

Other types of detachments and their uses are described in subsequent chapters. These detachments include—

- Counterreconnaissance detachment. (See chapter 5.)

- Urban detachment. (See chapter 5.)

- Security detachment. (See chapter 5.)

- Reconnaissance detachment. (See chapter 7).

- Movement support detachment. (See chapter 12.)

- Obstacle detachment. (See chapter 12.)

Unit symbols for detachments show the unit type and size of the “base” unit (battalion or company) around which the task organization was formed and whose headquarters serves as the headquarters for the detachment. Figures 2-10 through 2-12 on pages 2-9 and 2-10 show examples of unit symbols for various types of OPFOR detachments.

Platoons and Squads

In the OPFOR’s force structure, the smallest unit typically expected to conduct independent fire and maneuver is the platoon. Platoons are designed to be able to⎯

- Serve as the basis for forming a functional element or patrol.

- Fight as part of a company, battalion, or detachment.

- Execute tactical tasks. (A platoon will not be asked to perform two or more tactical tasks simultaneously.)

- Exert control over a small riot, crowd, or demonstration.

Platoons and squads within them can be task-organized for specific missions. Figures 2-13 and 2-14 show examples of unit symbols for various types of OPFOR task-organized platoons and squads.

Organizing the Tactical Battlefield

The OPFOR organizes the battlefield in such a way that it can rapidly transition between offensive and defensive actions and between linear and nonlinear dispositions. This flexibility can help the OPFOR adapt and change the nature of conflict to something for which the enemy is not prepared.

In his combat order, the commander specifies the organization of the battlefield from the perspective of his level of command. Within his unit’s AOR, as defined by the next-higher commander, he designates specific AORs for his subordinates, along with zones, objectives, and axes related to his own overall mission.

Areas of Responsibility

The OPFOR defines an area of responsibility (AOR) as the geographical area and associated airspace within which a commander has the authority to plan and conduct combat operations. An AOR is bounded by a limit of responsibility (LOR) beyond which the organization may not operate or fire without coordination through the next-higher headquarters. AORs may be linear or nonlinear in nature. Linear AORs may contain subordinate nonlinear AORs and vice versa. (See figures 2-15 through 2-18 on pages 2-12 and 2-13 for examples of tactical-level AORs. See chapters 3 and 4 for additional examples of AORs and zones in offense and defense.)

A combat order normally defines AORs (and zones within them) by specifying boundary lines in terms of distinct local terrain features through which a line passes. The order specifies whether each of those terrain features is included or excluded from the unit’s AOR or zones within it. Normally, a specified terrain feature is included unless the order identifies it as “excluded.” For example, the left boundary of the DTG AOR in figure 2-16 on page 2-12 runs from hill 108, to hill 250 (excluded), to junction of highway 52 and road 98, to the well. That example also illustrates that, even in a linear AOR, not all boundaries have to be straight lines.

It is possible, although not likely, that a higher commander may retain control of airspace over a lower commander’s AOR. This would be done through the use of standard airspace management measures.

Zones

AORs typically consist of three basic zones: battle zone, disruption zone, and support zone. An AOR may also contain one or more attack zones and/or kill zones. The various zones in an AOR have the same basic purposes within each type of offensive and defensive action. Zones may be linear or nonlinear in nature. The size of these zones depends on the size of the OPFOR units involved, engagement ranges of weapon systems, the terrain, and the nature of the enemy’s operation. Within the LOR, the OPFOR normally refers to two types of control lines. The support line separates the support zone from the battle zone. The battle line separates the battle zone from the disruption zone.

An AOR is not required to have any or all of these zones in any particular situation. A command might have a battle zone and no disruption zone. It might not have a battle zone, if it is the disruption force of a higher command. If it is able to forage, it might not have a support zone. The intent of this method of organizing the battlefield is to preserve as much flexibility as possible for subordinate units within the parameters that define the aim of the senior commander. An important feature of the basic zones in an AOR is the variations in actions that can occur within them in the course of a specific battle.

Disruption Zone

The disruption zone is the AOR of the disruption force. It is that geographical area and airspace in which the unit’s disruption force will conduct disruption tasks. This is where the OPFOR will set the conditions for successful combat actions by fixing enemy forces and placing long-range fires on them. Units in this zone begin the attack on specific components of the enemy’s combat system, to begin the disaggregation of that system. Successful actions in the disruption zone will create a window of opportunity that is exploitable in the battle zone.

Specific actions in the disruption zone can include—

- Attacking the enemy’s engineer elements. This can leave his maneuver force unable to continue effective operations in complex terrain⎯exposing them to destruction by forces in the battle zone.

- Stripping away the enemy’s reconnaissance assets while denying him the ability to acquire and engage OPFOR targets with deep fires. This includes an air defense effort to deny aerial attack and reconnaissance platforms from targeting OPFOR forces.

- Forcing the enemy to deploy early or disrupting his offensive preparations.

- Gaining and maintaining reconnaissance contact with key enemy elements.

- Deceiving the enemy as to the disposition of OPFOR units.

The disruption zone is bounded by the battle line and the LOR of the overall AOR. In linear offensive combat, the higher headquarters may move the battle line and LOR forward as the force continues successful offensive actions. Thus, the boundaries of the disruption zone will also move forward during the course of a battle. (See the example in figure 2-16 on page 2-12.) The higher commander can push the disruption zone forward or outward as forces adopt a defensive posture while consolidating gains at the end of a successful offensive battle and/or prepare for a subsequent offensive battle. Disruption zones may be contiguous or noncontiguous. They can also be “layered,” in the sense that one command’s disruption zone is part of the disruption zone of the next-higher command. (See an example of this layering in figure 2-17 on page 2-13.)

Battalions and below do not typically have their own disruption zones. However, they may conduct actions within the disruption zone of a higher command.

Battle Zone

The battle zone is the portion of the AOR where the OPFOR expects to conduct decisive actions. Forces in the battle zone will exploit opportunities created by actions in the disruption zone. Using all elements of combat power, the OPFOR will engage the enemy in close combat to achieve tactical decision in this zone.

In the battle zone, the OPFOR is typically trying to accomplish one or more of the following:

- Create a penetration in the enemy defense through which exploitation forces can pass.

- Draw enemy attention and resources to the action.

- Seize terrain.

- Inflict casualties on a vulnerable enemy unit.

- Prevent the enemy from moving a part of his force to impact OPFOR actions elsewhere on the battlefield.

A division or DTG does not always form a division- or DTG-level battle zone per se⎯that zone may be the aggregate of the battle zones of its subordinate units. In nonlinear situations, there may be multiple, noncontiguous brigade or BTG battle zones, and within each the division or DTG would assign a certain task to the unit charged to operate in that space. The brigade or BTG battle zone provides each of those subordinate unit commanders the space in which to frame his actions. Battalion and below units often have AORs that consist almost entirely of battle zones with a small support zone contained within them.

The battle zone is separated from the disruption zone by the battle line and from the support zone by the support line. In the offense, the commander may adjust the location of these lines in order to accommodate successful offensive action. In a linear situation, those lines can shift forward during the course of a successful attack. Thus, the battle zone would also shift forward. (For an example of this, see figure 2-16 on page 2-12.)

Support Zone

The support zone is that area of the battlefield designed to be free of significant enemy action and to permit the effective logistics and administrative support of forces. Security forces will operate in the support zone in a combat role to defeat enemy special operations forces. Camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D) measures will occur throughout the support zone to protect the force from standoff RISTA and precision attack. A division or DTG support zone may be dispersed within the support zones of subordinate brigades or BTGs, or the division or DTG may have its own support zone that is separate from subordinate AORs. If the battle zone moves during the course of a battle, the support zone would move accordingly. The support zone may be in a sanctuary that is noncontiguous with other zones of the AOR.

Attack Zone

An attack zone is given to a subordinate unit with an offensive mission, to delineate clearly where forces will be conducting offensive maneuver. Attack zones are often used to control offensive action by a subordinate unit inside a larger defensive battle or operation.

Kill Zone

A kill zone is a designated area on the battlefield where the OPFOR plans to destroy a key enemy target. A kill zone may be within the disruption zone or the battle zone. In the defense, it could also be in the support zone.

Functional Organization of Forces and Elements

An OPFOR commander specifies in his combat order the initial organization of forces or elements within his level of command, according to the specific functions he intends his various subordinate units to perform. At brigade or BTG and above, the subordinate units performing these functions are referred to as forces, while at battalion or BDET and below, they are called elements.

Note. This portion of chapter 2 provides a brief overview of functional organization as a key part of the OPFOR C2 process. This provides a common language and a clear understanding of how the commander intends his subordinates to fight functionally. Thus, subordinates that perform common tactical tasks such as disruption, fixing, assault, exploitation, security, deception, or main defense are logically designated as disruption, fixing, assault, exploitation, security, deception, or main defense forces or elements. OPFOR commanders prefer using the clearest and most descriptive term to avoid any confusion. For more detailed discussion and examples of the roles of various functional forces and elements in offense and defense, see chapters 3 and 4, respectively.

The OPFOR organizes and designates various forces and elements according to their function in the planned offensive or defensive action. A number of different functions must be executed each time an OPFOR unit attempts to accomplish a mission. The functions do not change, regardless of where the force or element might happen to be located on the battlefield. However, the function (and hence the functional designation) of a particular force or element may change during the course of the battle. The use of precise functional designations for every force or element on the battlefield allows for a clearer understanding by subordinate units of the distinctive functions their commander expects them to perform. It also allows each force or element to know exactly what all of the others are doing at any time. This knowledge facilitates the OPFOR’s ability to make quick adjustments and to adapt very rapidly to shifting tactical situations. This practice also assists in a more comprehensive planning process by eliminating the likelihood of some confusion (especially on graphics) of who is responsible for what. Omissions and errors are much easier to spot using these functional labels rather than relying on unit designators, numbers, or code words.

Note. A unit or group of units designated as a particular functional force or element may also be called upon to perform other, more specific functions. Therefore, the function of that force or element, or part(s) of it, may be more accurately described by a more specific functional designation. For example, a disruption force generally “disrupts,” but also may need to “fix” a part of the enemy forces. In that case, the entire disruption force could become the fixing force, or parts of that force could become fixing elements.

The various functions required to accomplish any given mission can be quite diverse. However, they can be broken down into two very broad categories: action and enabling.

Action Forces and Elements

One part of the unit or grouping of units conducting a particular offensive or defensive action is normally responsible for performing the primary function or task that accomplishes the overall mission goal or objective of that action. In most general terms, therefore, that part can be called the action force or action element. In most cases, however, the higher unit commander will give the action force or element a more specific designation that identifies the specific function or task it is intended to perform, which equates to achieving the objective of the higher command’s mission.

For example, if the objective of the action at detachment level is to conduct a raid, the element designated to complete that action may be called the raiding element. In offensive actions at brigade or BTG and higher, a force that completes the primary offensive mission by exploiting a window of opportunity created by another force is called the exploitation force. In defensive actions, the unit or grouping of units that performs the main defensive mission in the battle zone is called the main defense force or main defense element. However, in a maneuver defense, the main defensive action is executed by a combination of two functional forces: the contact force and the shielding force.

Enabling Forces and Elements

In relation to the action force or element, all other parts of the organization conducting an offensive or defensive action provide enabling functions of various kinds. In most general terms, therefore, each of these parts can be called an enabling force or enabling element. However, each subordinate force or element with an enabling function can be more clearly identified by the specific function or task it performs. For example, a force that enables by fixing enemy forces so they cannot interfere with the primary action is a fixing force. Likewise, an element that clears obstacles to permit an action element to accomplish a detachment’s tactical task is a clearing element.

Other types of enabling forces or elements designated by their specific function may include—

- Disruption force or element. Operates in the disruption zone; disrupts enemy preparations or actions; destroys or deceives enemy reconnaissance; begins reducing the effectiveness of key components of the enemy’s combat system.

- Fixing force or element. Fixes the enemy by preventing a part of his force from moving from a specific location for a specific period of time, so it cannot interfere with the primary OPFOR action.

- Security force or element. Provides security for other parts of a larger organization, protecting them from observation, destruction, or becoming fixed.

- Deception force or element. Conducts a deceptive action (such as a demonstration or feint) that leads the enemy to act in ways prejudicial to enemy interests or favoring the success of an OPFOR action force or element.

- Support force or element. Provides support by fire; other combat or combat service support; or C2 functions for other parts of a larger organization.

Other Forces and Elements

In initial orders, some subordinates are held in a status pending determination of their specific function. At the commander’s discretion, some forces or elements may be held out of initial action, in reserve, so that he may influence unforeseen events or take advantage of developing opportunities. These are designated as reserves (reserve force or reserve element). If and when such units are subsequently assigned a mission to perform a specific function, they receive the appropriate functional force or element designation. For example, a reserve force in a defensive operation might become the counterattack force.

In defensive actions, there may be a particular unit or grouping of units that the OPFOR commander wants to be protected from enemy observation or fire, to ensure that it will be available after the current battle or operation is over. This is designated as the protected force.

Command of Forces and Elements

Each of the separate functional forces or elements—even when it involves a grouping of multiple units—has an identified commander. This is often the senior commander of the largest subordinate unit assigned to that force or element.

Note. A patrol is a platoon- or squad-size grouping task-organized to accomplish a specific reconnaissance and/or security mission. There are two basic types of patrol: fighting patrol and reconnaissance patrol. Both are described in chapter 8.

Headquarters, Command, and Staff

All OPFOR levels of command share parallel staff organization. However, command and staff elements at various levels are tailored to match differences in scope and span of control.

DTG or Division Command Group and Staff

A DTG or division headquarters includes the command group and the staff. (See figure 2-19 on page 2-18.) These elements perform the functions required to control the activities of forces preparing for and conducting combat.

The primary functions of headquarters are to⎯

- Make decisions.

- Plan combat actions that accomplish those decisions.

- Acquire and process the information needed to make and execute effective decisions.

- Support the missions of subordinates.

The commander exercises C2 functions through his command group, staff, and subordinate commanders.

Command Group

The command group consists of the commander, deputy commander (DC), and chief of staff (COS). Together, they direct and coordinate the activities of the staff and of subordinate forces.

Commander

The commander directs subordinate commanders and, through his staff and liaison officers, controls any supporting elements. OPFOR commanders have complete authority over their subordinates and overall responsibility for those subordinates’ actions. Under the fluid conditions of modern warfare, even in the course of carefully planned actions, the commander must accomplish assigned missions on his own initiative without constant guidance from above.

The commander is responsible for—

- The combat capability of subordinate units.

- The organization of combat actions.

- The maintenance of uninterrupted C2.

- The successful conduct of combat missions.

The commander examines and analyzes the mission he receives (that is, he determines his forces’ place in the senior commander’s concept of the battle or operation). He may do this alone or jointly with the COS. He then gives instructions to the COS on preparing his forces and staff for combat. He also provides instructions about the timing of preparations. The commander makes his own assessment of intelligence data supplied by the chief of intelligence. Then, with advice from all the primary staff officers, he makes an assessment of his own forces. After discussing his deductions and proposals with the operations officer and his staff, the commander reaches a decision, issues combat missions to subordinates, and gives instructions about planning the battle. He then directs coordination within his organization and with adjacent forces and other elements operating in his AOR.

During the course of combat, the commander must constantly evaluate the changing situation, predict likely developments, and issue new combat missions in accordance with his vision of the battlefield. He also keeps his superiors informed as to the situation and character of friendly and enemy actions and his current decisions.

Deputy Commander

In the event the commander is killed or incapacitated, the deputy commander (DC) would assume command. Barring that eventuality, the primary responsibility of the DC of a DTG or division is to command the IFC. As IFC commander, he is responsible for executing tactical-level fire support in a manner consistent with the commander’s intent.

Chief of Staff

Preeminent among OPFOR staff officers is the chief of staff (COS) position (found at every level from the General Staff down to battalion). He exercises direct control over the primary staff. During combat, he is in charge of the main CP when the commander moves to the forward CP. He has the power to speak in the name of the commander and DC, and he normally countersigns all written orders and combat documents originating from the commander’s authority. He alone has the authority to sign orders for the commander or DC and to issue instructions in the commander’s name to subordinate units. In emergency situations, he can make changes in the tasks given to subordinate commanders. Thus, it is vital that he understands not merely the commander’s specific instructions but also his general concept and train of thought. He controls the battle during the commander’s absences.

The COS is a vital figure in the C2 structure. His role is to serve as the director of staff planning and as coordinator of all staff inputs that assist the commander’s decisionmaking. He is the commander’s and DC’s focal point for knowledge about the friendly and enemy situation. He has overall responsibility for providing the necessary information for the commander to make decisions. Thus, he plays a key role in structuring the overall reconnaissance effort, which is a combined arms task, to meet the commander’s information requirements.

Staff

A staff provides rapid, responsive planning for combat activity, and then coordinates and monitors the execution of the resulting plans on behalf of the commander. Proper use of this staff allows the commander to focus on the most critical issues in a timely manner and to preserve his energies. For additional detail on the organization of the command group and staff, see FM 7-100.4.

The staff releases the commander from having to solve administrative and technical problems, thereby allowing him to concentrate on the battle. The primary function of the staff is to plan and prepare for combat. Evaluation and knowledge of the operational environment is fundamental to the decisionmaking process and the direction of troops. After the commander makes the decision, the staff must organize, coordinate, disseminate, and support the missions of subordinates. Additionally, it is their responsibility to train and prepare troops for combat, and to monitor the pre-combat and combat situations.

In the decision making and planning process, the staff—

- Prepares the data and estimates the commander uses to make a decision.

- Plans and implements the basic measures for comprehensive support of a combat action.

- Organizes communications with subordinate and adjacent headquarters and the next-higher staff.

- Monitors the activities of subordinate staffs.

- Coordinates ongoing activity with higher-level and adjacent staffs during a battle or operation.

The staff consists of three elements: the primary staff, the secondary staff, and the functional staff. Figure 2-19 on page 2-18 depicts the primary, secondary, and functional staff officers of a DTG or division headquarters. (It does not show the liaison teams, which support the primary, secondary, and functional staff.)

Primary and Secondary Staff

Each member of the primary staff heads a staff section. Within each section are two or three secondary staff officers heading subsections subordinate to that primary staff officer.

Operations Officer. The operations officer heads the operations section, and conducts planning and prepares plans and orders. Thus, the operations section is the principal staff section. It includes current operations, future operations, and airspace operations subsections, as well as the functional staff.

The operations officer also serves as deputy chief of staff. He is responsible for—

- Training.

- Formulating and writing plans, combat orders, and important combat reports.

- Monitoring the work of all other staff sections.

- Remaining knowledgeable of the current situation.

- Being ready to present information and recommendations concerning the situation.

In coordination with the intelligence and information section, the operations officer keeps the commander informed on the progress of the battle and the overall operation.

Specific duties of the operations section include—

- Assisting the commander in the making and execution of combat decisions.

- Collecting information concerning the situation of friendly forces.

- Preparing and disseminating orders, plans and reports, summaries, and situation overlays.

- Providing liaison for the exchange of information within the headquarters and with higher, subordinate, and adjacent units.

- Organizing the main CP.

- Organizing troop movement and traffic control.

- Coordinating the organization of reconnaissance with the intelligence and information section.

The chief of current operations is a secondary staff officer who proactively monitors the course of current operations and coordinates the actions of forces to ensure execution of the commander’s intent. He serves as the representative of the commander, COS, and operations officer in their absence and has the authority to control forces in accordance with the battle plan.

The chief of future operations is a secondary staff officer who heads the planning staff and ensures continuous development of future plans and possible branches, sequels, and contingencies. While the commander and the chief of current operations focus on the current battle, the chief of future operations and his subsection monitor the friendly and enemy situations and their implications for future battles. They try to identify any developing situations that require command decisions and/or adaptive measures. They advise the commander on how and when to make adjustments to the battle plan during the fight. Planning for various contingencies and anticipated opportunities can facilitate immediate and flexible response to changes in the situation.

The chief of airspace operations (CAO) is a secondary staff officer who is responsible for the control of the division’s or DTG’s airspace. See chapters 9 and 10 for further information on his duties.

Intelligence Officer. The intelligence officer heads the intelligence and information section, which consists of the reconnaissance subsection, the information warfare (INFOWAR) subsection, and the communications subsection. The intelligence officer is responsible for the acquisition, synthesis, analysis, dissemination, and protection of all information and intelligence related to and required by the division’s or DTG’s combat actions. He ensures the commander’s intelligence requirements are met. He provides not only intelligence on the current and future operational environment, but also insight on opportunities for adaptive and creative responses to ongoing operations. The intelligence officer works in close coordination with the chief of future operations to establish feedback and input for future operations and the identification of possible windows of opportunity.

The intelligence officer also formulates the division’s or DTG’s INFOWAR plan and must effectively task-organize his staff resources to conduct and execute INFOWAR in a manner that supports the strategic INFOWAR plan. He is responsible for the coordination of all necessary national or theater- level assets in support of the INFOWAR plan and executes staff supervision over the INFOWAR and communications plans. He is supported by three secondary staff officers: the chief of reconnaissance, the chief of INFOWAR, and the chief of communications.

The chief of reconnaissance develops reconnaissance plans, gathers information, and evaluates data on the operational environment. During combat, he supervises the efforts of subordinate reconnaissance units and reconnaissance staff subsections of subordinate units. Specific responsibilities of the reconnaissance subsection include—

- Continuously collecting, analyzing, and disseminating information on the operational environment to the commander and subordinate, higher, and adjacent units.

- Organizing reconnaissance missions, including requests for aerial reconnaissance, in coordination with the operations section and in support of the INFOWAR plan.

- Preparing the reconnaissance plan, in coordination with the operations section.

- Preparing the reconnaissance portion of battle plans and combat orders.

- Preparing intelligence reports.

- Supervising the exploitation of captured enemy documents and materiel.

- Supervising interrogation and debriefing activities throughout the command.

- Providing targeting data for long-range fires.

The chief of information warfare is responsible supervising the execution of the division’s or DTG’s INFOWAR plan. (See chapter 6 for details and components of the INFOWAR plan.) These responsibilities include⎯

- Coordinating the employment of INFOWAR assets, both those subordinate to the division or DTG and those available at higher levels.

- Planning for and supervising all information protection and security measures.

- Supervising the implementation of the deception and perception management plans.

- Working with the operations staff to ensure that targets scheduled for destruction support the INFOWAR plan, and if not, resolving conflicts between INFOWAR needs and operational needs.

- Recommending to the intelligence officer any necessary actions required to implement the INFOWAR plan.

The chief of communications develops a communications plan for the command that is approved by the intelligence officer and COS. He organizes communications with subordinate, adjacent, and higher headquarters. To ensure that the commander has continuous and uninterrupted control, the communications subsection plans the use of all forms of communications, to include satellite communications (SATCOM), wire, radio, digital, cellular, and couriers. Specific responsibilities of the communications subsection include⎯

- Establishing SATCOM and radio nets.

- Establishing call signs and radio procedures.

- Organizing courier and mail service.

- Operating the command’s message center.

- Supervising the supply, issue, and maintenance of signal equipment.

An additional and extremely important role of the communications officer is to ensure the thorough integration of interagency, allied, subordinate, supporting, and affiliated forces into the division’s or DTG’s communications and C2 structure. The division or DTG headquarters is permanently equipped with a full range of C2 systems compatible with each of the services of the State’s Armed Forces as well as with other government agencies commonly operating as part of DTGs.

Resources Officer. The resources officer is responsible for the requisition, acquisition, distribution, and care of all of the division’s or DTG’s resources, both human and materiel. He ensures the commander’s logistics and administrative requirements are met and executes staff supervision over the command’s logistics and administrative procedures. (Logistics procedures are detailed in chapter 14.) He is supported by two secondary staff officers: the chief of logistics and the chief of administration. One additional major task of the resources officer is to free the commander from the need to bring his influence to bear on priority logistics and administrative functions. He is also the officer in charge of the sustainment CP.

The chief of logistics heads the logistics system. He is responsible for managing the order, receipt, and distribution of supplies to sustain the command. He is responsible for the condition and combat readiness of armaments and related combat equipment and instruments. He is also responsible for their supply, proper utilization, repair, and evacuation. He oversees the supply and maintenance of the division’s or DTG’s combat and technical equipment. These responsibilities encompass the essential wartime tasks of organizing and controlling the division’s or DTG’s recovery, repair, and replacement system. During combat, he keeps the commander informed on the status of the division’s or DTG’s equipment.

The chief of administration supervises all personnel actions and transactions in the division or DTG. His subsection—

- Maintains daily strength reports.

- Records changes in TOE of units in the AFS.

- Assigns personnel.

- Requests replacements.

- Records losses.

- Administers awards and decorations.

- Collects, records, and disposes of war booty.

Functional Staff

The functional staff consists of experts in a particular type of military operation or function. (See figure 2-19 on page 2-18.) These experts advise the command group and the primary and secondary staff on issues pertaining to their individual areas of expertise. The functional staff consists of the following elements:

- Integrated fires.

- Force protection.

- Special-purpose operations.

- Weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

- Population management.

- Infrastructure management.

In peacetime, the functional staff is a cadre with personnel assigned from appropriate branches. It has enough personnel to allow continuous 24-hour capability and the communications and information management tools to allow them to support the commander’s decisionmaking process and exercise staff supervision over their functional areas throughout the AOR. In wartime, the functional staff receives liaison teams from subordinate, supporting, allied, and affiliated units that perform tasks in support of those functional areas.

Chief of Integrated Fires. The chief of integrated fires is responsible for integrating C2 and RISTA means with fires and maneuver. He works closely with the division or DTG chief of reconnaissance and the IFC staff. He also coordinates with the chief of INFOWAR to ensure that deception and protection and security measures contribute to the success of fire support of offensive and defensive actions.

Chief of Force Protection. The chief of force protection is responsible for coordinating activities to prevent or mitigate the effects of hostile actions against OPFOR personnel, resources, facilities, and critical information. This protection includes—

- Air, space, and missile defense.

- CBRN protection.

- Defensive INFOWAR.

- Antiterrorism measures.

- Counterreconnaissance.

- Engineer survivability measures.

This subsection works closely with those of the chief of WMD and the chief of INFOWAR. Liaison teams from internal security, air defense, chemical defense, and engineer forces provide advice within their respective areas of protection.

Chief of Special-Purpose Operations. The chief of special-purpose operations is responsible for planning and coordinating the actions of SPF units allocated to a DTG or supporting it from OSC level. When possible, this subsection receives liaison teams from any affiliated forces that act in concert with the SPF.

Chief of WMD. The chief of WMD is responsible for planning the offensive use of WMD. This functional staff element receives liaison teams from any subordinate or supporting units that contain WMD delivery means.

Chief of Population Management. The chief of population management is responsible for coordinating the actions of Internal Security Forces, as well as psychological warfare, perception management, civil affairs, and counterintelligence activities. This subsection works closely with the chief of INFOWAR and receives liaison teams from psychological warfare, civil affairs, counterintelligence, and Internal Security Forces units allocated to the DTG or operating within the division’s or DTG’s AOR. There is always a representative of the Ministry of the Interior, and frequently one from the Ministry of Public Information.

Chief of Infrastructure Management. The chief of infrastructure management is responsible for establishing and maintaining—

- Roads.

- Airfields.

- Railroads.

- Hardened structures (warehouses and storage facilities).

- Inland waterways.

- Ports.

- Pipelines.

He coordinates with the division or DTG resources officer regarding improvement and maintenance of supply and evacuation routes. He exercises staff supervision or cognizance over the route construction and maintenance functions of both civil and combat engineers operating in the division’s or DTG’s AOR. He coordinates with civilian agencies and the division or DTG chief of communications to ensure adequate telecommunications support.

Liaison Teams

Liaison teams support brigade and division staffs (as well as those of tactical groups and detachments) with detailed expertise in the mission areas of their particular branch or service. They also provide direct communications to subordinate and supporting units executing missions in those areas. They are not a permanent part of the staff structure. Liaison team chiefs speak for the commanders of their respective units. All liaison teams are under the direct control of the operations section. The operations officer is responsible for ensuring proper placement and utilization of the teams.

Liaison teams to DTGs and divisions are generally organized with a liaison team chief, two current operations officers or senior NCOs, and two future operations officers or senior NCOs. This gives liaison teams the ability to conduct continuous operations and simultaneously execute current plans and develop future plans. The staff will also receive liaison teams from multinational and interagency subordinates and from affiliated forces. The number and types of liaison teams is fluid and is determined by many factors. Liaison teams provide their own equipment. A detailed breakout of personnel and equipment of a typical liaison team is available in FM 7-100.4.

BTG or Brigade Command Group and Staff

Generally speaking, the command group and staff of a BTG or brigade are smaller versions of those previously described for DTG or division level. The following paragraphs highlight the differences other than size.

Command Group

The BTG or brigade command group consists of the commander, DC, and COS. The primary difference is that the DC does not serve as IFC commander, since there is no IFC at this level of command.

Commander

Compared to higher-level commands, much more of the BTG or brigade fight is the direct fire battle. Therefore, BTG or brigade commanders typically spend more time at the forward CP or with forward-deployed subordinate units than do DTG or division commanders.

Deputy Commander

At the BTG or brigade (and below), IFCs do not exist. Thus, the DC is not also the commander of the IFC.

Chief of Staff

At BTG or brigade level, the COS position retains all the characteristics of the DTG or division COS position. The COS is in charge of the main CP in the absence of the commander.

Staff

BTG and brigade staffs are naturally smaller and less capable than DTG and division staffs. In particular, the sections responsible for planning are much reduced, providing the BTG or brigade with the ability to plan combat actions only 24 to 48 hours into the future.

Another key difference from the DTG or division staff is that the functional staff is organized differently. A BTG or brigade functional staff consists of the following elements:

- Fire support coordination.

- Force protection.

- Special-purpose operations.

- WMD.

- Population management.

- Infrastructure management.

Note. There is no chief of integrated fires or dedicated staff element for integrating fires at the BTG or brigade level, since this level of command has no IFC. However, the staff at that level does include a chief of fire support coordination and a fire support coordination staff element within the functional staff of the operations section. This staff performs all of the necessary coordination between constituent, dedicated, and supporting fire support elements. See FM 7-100.4.

Liaison teams support brigade and BTG staffs with detailed expertise in the mission areas of subordinate and supporting units. A typical liaison team to a BTG or brigade staff consists of four personnel: a team chief, an assistant team chief, a staff officer or NCO, and their driver. A detailed breakout of personnel and equipment of a typical liaison team is available in FM 7-100.4.

Battalion or BDET Command Section and Staff

The OPFOR battalion or BDET headquarters is function-based and is composed of two sections— the command section and the staff section. They are highly streamlined and do not contain the robust planning and control capabilities necessary for higher staffs. For details on the personnel and equipment in the battalion command and staff sections, see, FM 7-100.4.

Command Section

The battalion command section consists of the commander, the DC, their vehicle drivers and radio telephone operators (RTOs). The COS is part of both the command section and the staff. On the battlefield, however, he is generally located with the staff section because he exercises direct control over the battalion staff. He is also in direct charge of the main CP in the absence of the commander. In maneuver units where the battalion command section employs combat vehicles, the command section may include vehicle gunners as well. Often a staff officer or NCO from the operations and/or intelligence section accompanies the battalion command section on the battlefield.

The battalion commander positions himself where he can best influence the critical action on the battlefield. The DC is typically supervising the execution of the battalion’s second most critical operation and separate from the battalion commander so that both are not killed by the same engagement. The DC’s vehicle may be used as a forward or auxiliary CP or observation post (OP).

Staff

At battalion level, the staff consists of two elements: the primary staff and the secondary staff. There is no functional staff below brigade or BTG level. Figure 2-20 on page 2-27 depicts the staff of a combat battalion headquarters and the liaison teams that support it.

The battalion staff consists of the operations officer (who also serves as the deputy COS), the assistant operations officer, the intelligence officer, and the resources officer. At battalion, typically each member of the primary staff heads a small staff section consisting of themselves and two other soldiers of the correct specialty. Two staff NCOs serve as day and night shift leaders in the main CP along with several enlisted soldiers. For more specifics, see FM 7-100.4.

The battalion staff has the mission to coordinate battlefield functions and to anticipate the battalion’s needs 6-12 hours into the future. It supports the commander in the completion of combat orders and ensures his intent is being executed. It is not capable of executing long-range planning or supporting complex, joint, or interagency operations without augmentation.

The staff section operates the main CP. Staff vehicles are configured to supplement operations or for use as a forward or auxiliary CP or as an OP. In the latter case, they will be manned with appropriate staff personnel. The vehicles in the signal platoon may also be used. The COS may choose to ride in a utility vehicle or other vehicle.

Liaison teams may or may not be attached to the battalion. They are not a permanent part of the battalion staff structure. They may support the battalion staff with detailed expertise in the mission areas of their own particular branch or service. They provide direct communications to subordinate and supporting units executing missions in those areas. The battalion staff may also receive liaison teams from multinational and interagency subordinates and from affiliated forces. The operations officer is responsible for ensuring proper placement and utilization of the teams. The number and types of liaison teams is fluid and is determined by many variables. A typical liaison team consists of four personnel: a team chief, an assistant team chief, a staff NCO, and a driver/RTO. Liaison teams augmenting the battalion staff provide their own equipment. A detailed breakout of personnel and equipment of a typical liaison team is available in FM 7-100.4.

Staff Command

At BTG or brigade level and above, the OPFOR does not use the concept of commanders of combat support units acting as senior staff officers. However, in order to streamline staff functions at battalion, the OPFOR relies on commanders of supporting arms units to exercise staff supervision over their areas.

The leaders of the battalion’s specialty platoons serve in a staff command role to coordinate key battlefield functions:

- The commander of the mortar battery also serves as the chief of fire support coordination for the battalion. (The assistant operations officer functions as the chief of fire support in those units without a mortar battery but still requiring fire and/or targeting support.)

- The signal platoon leader also serves as the battalion chief of communications.

- The platoon leader of the reconnaissance platoon serves as the battalion chief of reconnaissance.

- The platoon leader of the materiel support platoon serves as the battalion chief of logistics. (The battalion resources officer may also function as chief of administration.)

The chiefs of reconnaissance and communications coordinate with the main and forward CPs, and the chief of logistics operates the battalion trains.

The OPFOR will only employ staff command functions—

- In secondary staff areas (such as administration, logistics, reconnaissance, and communications).

- With commanders who have sufficient control over the area that the additional staff supervision functions are not a serious burden to their command responsibilities.

Company or CDET Command and Staff

The basic structure of OPFOR companies or CDETs includes a headquarters and service section. This section consists of a command team, a support team, and a supply and transport team. Key personnel are—

- Command Team. Company commander and staff NCO.

- Support Team. DC and first sergeant.

- Supply and Transport Team. Supply sergeant.

Command Posts

The OPFOR plans to exercise tactical control over its wartime forces from an integrated system of CPs. It has designed this system to ensure uninterrupted control of forces. All OPFOR levels of command share a parallel CP structure, tailored to match the differences in scope and span of control.

CPs are typically formed in three parts: a control group, a support group, and a communications group. The control group includes members of the command group or section and staff. The support group consists of the transport and logistics elements. Whenever possible, the communications group is remoted from the control and support groups because of its large number of signal vans, generators, and other special vehicles that would provide a unique signature.

Because the OPFOR expects its C2 to come under heavy attack in wartime, its military planners have created a CP structure that emphasizes survivability through dispersal, stringent security measures, redundancy, and mobility. They have constructed a CP system that can sustain damage with minimum disruption to the actual C2 process. In the event of disruption, they can quickly reestablish control. This extensive system of CPs extends from the hardened command facilities of the National Command Authority to the specially designed command vehicles from which OPFOR tactical commanders control their units. Tactical CPs and most operational-level CPs have been designed to be very mobile and smaller than comparable enemy CPs. The number, size, and types of CPs depend on the level of command.

Command Post Types

OPFOR ground forces use five basic and three special types of CPs. Not all levels of command use all types at all times. (See table 2-2, where parentheses indicate that a type of CP may or may not be employed at a certain level.) The redundancy provided by multiple CPs helps to ensure that the C2 process remains survivable.

| Level of Command | CP Types | |||||||

| Main CP | IFC CP | Forward CP | Sustainment CP | Airborne CP | Alternate CP | Auxiliary CP | Deception CP | |

| DTG/Division | X | X | X | X | (X) | (X) | (X) | (X) |

| BTG/Brigade | X | - | X | X | (X) | (X) | (X) | (X) |

| BDET/Battalion | X | - | X | X | - | (X) | - | (X) |

| CDET/Company | - | - | X | X | - | - | - | (X) |

For brevity, OPFOR plans and orders may use acronyms for the various types of CP. Thus, main CP may appear as MCP, integrated fires command CP as IFC CP, forward CP as FCP, sustainment CP as either SCP or SUSCP, airborne CP as AIRCP, alternate CP as ALTCP, auxiliary CP as AUXCP, and deception CP as DCP.

Main Command Post

The main CP generally is located in a battle zone or in a key sanctuary area or fortified position. It contains the bulk of the staff. The COS directs its operation. Its primary purpose is to simultaneously coordinate the activities of subordinate units not yet engaged in combat and plan for subsequent missions. The particular emphasis on planning in the main CP is on the details of transitioning between current and future operations. The main CP is the focus of control. It is less mobile and much larger than the forward CP. It makes use of hardened sites when possible.

The COS directs the staff in translating the commander’s decisions into plans and orders. He also coordinates the movement and deployment of all subordinate units not yet in combat and monitors their progress and combat readiness. In addition to the COS, personnel present at the main CP include the liaison teams from subordinate, supporting, allied, and affiliated units, unless their presence is required in another CP.

IFC Command Post

The DC of a DTG or division directs the IFC from the IFC CP. The IFC CP possesses the communications, airspace control, and automated fire control systems required to integrate RISTA means and execute long-range fires. Each secondary staff subsection and some functional staff subsections have an element dedicated to the IFC CP. The IFC CP includes liaison teams from fire support, army aviation, and long-range reconnaissance elements. The IFC CP is typically separated from the main CP. Also for survivability, the various sections of the IFC headquarters that make up the IFC CP do not necessarily have to be located in one place.

Forward Command Post

A commander often establishes a forward CP with a small group of selected staff members. Its purpose is to provide the commander with information and communications that facilitate his decisions. The forward CP is deployed at a point from which he can more effectively and personally observe and influence the battle.

The personnel at the forward CP are not permanent. The assignment of officers to accompany the commander is dependent on the mission, situation, and availability of officers, communications, and transport means. Officers who may accompany the commander include the operations officer and the chief of reconnaissance. Other primary and or secondary staff officers may also deploy with the forward CP, depending on the needs of the situation. The secondary staff contains enough personnel to man the forward CP without degrading its ability to man the main or IFC CPs.

When formed, and when the commander is present, the forward CP is the main focus of command, though the COS (remaining in the main CP) has the authority to issue directives in the commander’s absence.

Sustainment Command Post

The resources officer establishes and controls the sustainment CP. This CP is deployed in a position to permit the supervision of execution of sustainment procedures and the movement of support troops, typically in the support zone. It contains staff officers for fuel supply, medical support, combat equipment repair, ammunition supply, clothing supply, food supply, prisoner-of-war, and other services. It interacts closely with the subordinate units to ensure sustained combat capabilities. In nonlinear situations, multiple sustainment CPs may be formed.

Airborne Command Post

To maintain control in very fluid situations, when subordinates are spread over a wide area, or when the other CPs are moving, a commander may use an airborne CP. This is very common in DTG- or division-level commands, typically aboard helicopters.

Alternate Command Post

The alternate CP provides for the assumption of command should the CP containing the commander be incapacitated. The alternate CP is a designation given to an existing CP and is not a separately established element. The commander will establish which CP will act as an alternate CP to take command if the main (or forward) CP is destroyed or disabled. For example, the commander might designate the IFC CP as the alternate CP during a battle where long-range fires are critical to mission success. For situations that require reconstituting, he might designate the sustainment CP instead. Alternate CPs are also formed when fighting in complex terrain, or if the organization is dispersed over a wider area than usual and lateral communication is difficult.

Auxiliary Command Post

The commander may create an auxiliary CP to provide C2 over subordinate units fighting on isolated or remote axes. He may also use it in the event of disrupted control or when he cannot adequately maintain control from the main CP. An officer appointed at the discretion of the commander mans it.

Deception Command Post

As part of the overall INFOWAR plan, the OPFOR very often employs deception CPs. These are complex, multi-sensor-affecting sites integrated into the overall deception plan to assist in achieving battlefield opportunity by forcing the enemy to focus their command and control warfare efforts against meaningless positions.

Command Post Movement

Plans for relocating the CPs are prepared by the operations section. The CPs are deployed and prepared in order to ensure that they are reliably covered from enemy ground and aerial reconnaissance, or from attack by enemy raiding forces.

Commanders deploy CPs in depth to facilitate control of their AORs. During lengthy moves, CPs may bound forward along parallel routes, preceded by reconnaissance elements that select the new locations. Normally, the main and forward CPs do not move at the same time, with one moving while the other is set up and controlling the battle. During an administrative movement, when there is little or no likelihood of contact with the enemy, a CP may move into a site previously occupied by another CP. However, during a tactical movement or when contact is likely, the OPFOR will not occupy a site twice, because to do so would increase the chances of an enemy locating a CP. While on the move, CPs maintain continuous contact with subordinates, higher headquarters, and flanking organizations. During movement halts, the practice is to disperse the CP in a concealed area, camouflaging it if necessary and locating radio stations and special vehicles some distance from the control and support groups. Because of dispersion in a mobile environment, CPs are often responsible for their own local ground defenses.

During the movement of a main CP, the OPFOR maintains continuity of control by handing over control to either the forward or airborne CP or, more rarely, to the alternate CP. Key staff members often move to the new location by helicopter to reduce the time spent away from their posts. Before any move, headquarters’ troops carefully reconnoiter and mark the new location. Engineer preparation provides protection and concealment.

Command Post Location

The OPFOR locates CPs in areas affording good concealment, with good road network access being a secondary consideration. It situates CPs so that no single weapon can eliminate more than one. Remoting communications facilities lessens the chance of the enemy’s locating the actual command element by radio direction finding.

During some particularly difficult phases of a battle, where close cooperation between units is essential, the forward CP of one element may be colocated with the forward or main CP of another. Examples are the commitment of an exploitation force or the passing of one organization through another.

Command Post Security

Security of CPs is important, and the OPFOR takes a number of measures to ensure it. CPs are a high priority for air defense protection. Ideally, main CPs also locate near reserve elements to gain protection from ground attack. Nevertheless, circumstances often dictate that they provide for their own local defense. Engineers normally dig in and camouflage key elements.

Good camouflage, the remoting of communications facilities, and the deployment of alternate CPs make most of the C2 structure fairly survivable. Nevertheless, one of the most important elements, the forward CP, often remains vulnerable. It forms a distinctive, if small, grouping, usually well within enemy artillery range. The OPFOR will therefore typically provide key CPs with sufficient engineer and combat arms support to protect them from enemy artillery or special operations raids.

Command and Control Systems

The OPFOR commander’s C2 requirements are dictated generally by the doctrine, tactics, procedures, and operational responsibilities applicable to commanders at higher echelons. Battlefield dispersion, mobility, and increasing firepower under conventional or WMD conditions require reliable, flexible, and secure C2.

Expanding C2 requirements include the need for⎯

- High mobility of combat headquarters and subordinate elements.

- Rapid collection, analysis, and dissemination of information as the basis for planning and decisionmaking.

- Maintaining effective control of forces operating in a hostile INFOWAR environment.

Supporting communications systems, which are the principal means of C2, must have a degree of mobility, reliability, flexibility, security, and survivability comparable to the C2 elements being supported.

Modern warfare has shifted away from large formations arrayed against one another in a linear fashion, to maneuver warfare conducted across large areas with more lethal, yet smaller, combat forces. C2 must provide the reliable, long-range communications links necessary to control forces deployed over greater distances. In order to move with the maneuver forces, the communications systems must be highly mobile.

Communications