Chapter 3: Offense

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.2 Opposing Force Tactics.

The offense carries the fight to the enemy. The OPFOR sees this as the decisive form of combat and the ultimate means of imposing its will on the enemy. While conditions at a particular time or place may require the OPFOR to defend, defeating an enemy force ultimately requires shifting to the offense. Even within the context of defense, victory normally requires some sort of offensive action. Therefore, OPFOR commanders at all levels seek to create and exploit opportunities to take offensive action, whenever possible.

The aim of offense at the tactical level is to achieve tactical missions in support of an operation. A tactical command ensures that its subordinate commands thoroughly understand both the overall goals of the operation and the specific purpose of a particular mission they are about to execute. In this way, subordinate commands may continue to execute the mission without direct control by a higher headquarters, if necessary.

Contents

- 1 Purpose of the Offense

- 2 Planning the Offense

- 3 Functional Organization of Elements for the Offense--Detachments, Battalions, and Below

- 4 Preparing for the Offense

- 5 Executing the Offense

- 6 Types of Offensive Action--Tactical Groups, Divisions, and Brigades

- 7 Tactical Offensive Actions--Detachments, Battalions, and Below

- 7.1 Assault

- 7.2 Ambush

- 7.3 Raid

- 7.4 Functional Organization for a Raid

- 7.5 Reconnaissance Attack

Purpose of the Offense

All tactical offensive actions are designed to achieve the goals of an operation through active measures. However, the purpose or reason, of any given offensive mission varies with the situation, as determined through the decision making process. The primary distinction among types of offensive missions is their purpose which is defined by what the commander wants to achieve tactically. Thus, the OPFOR recognizes six general purposes of tactical offensive missions:

- Gain freedom of movement.

- Restrict freedom of movement.

- Gain control of key terrain, personnel, or equipment.

- Gain information.

- Dislocate.

- Disrupt.

These general purposes serve as a guide to understanding the design of an offensive mission and not as a limit placed on a commander as to how he makes his intent and aim clear. These are not the only possible purposes of tactical missions but are the most common.

These six general purposes are only a few of the many reasons the OPFOR might have for attacking an enemy, a potential enemy, a neighbor, or someone else. The true intent of an attack may reside at the operational or strategic level, but the attack is executed at the tactical level. Therefore, the actual reason for the attack may often be difficult to discern. In addition to those listed above, a few other reasons to attack may be to destroy, deceive, demonstrate dominance, deter (such as to discourage a neighbor from joining a coalition or alliance), or any number of other purposes.

In each of these general purposes of tactical offensive missions, the enemy may be destroyed or attrited to varying levels. Destruction is an inherent part of any attack. The critical tactical factor to the OPFOR commander initially is not how to conduct the offensive mission—but rather why. Once the why has been decided the method with the best chance of achieving tactical success becomes the how.

Attack to Gain Freedom of Movement

An attack to gain freedom of movement creates a situation in an important part of the battlefield where other friendly forces can maneuver in a method of their own choosing with little or no opposition. Such an attack can take many forms, of which the following are some examples:

- Seizing an important mobility corridor to prevent a counterattack into the flank of another moving force.

- Destroying an air defense unit so that a combat helicopter may use an air avenue of approach at lower risk.

- Breaching a complex obstacle to allow an exploitation force to pass through.

- Executing security tasks such as screen, guard, and cover. Such tasks may involve one or more attacks to gain freedom of movement as a component of the scheme of maneuver.

Attack to Restrict Freedom of Movement

An attack to restrict freedom of movement prevents the enemy from maneuvering as he chooses. Restricting attacks can deny key terrain, ambush moving forces, dominate airspace, or fix an enemy formation. Tactical tasks often associated with restricting attacks are ambush, block, canalize, contain, fix, interdict, and isolate. The attrition of combat elements and equipment may also limit the enemy units’ ability to move. An example of this may be a preemptive strike on the enemy’s water-crossing or mineclearing equipment.

Attack to Gain Control of Key Terrain, Personnel, or Equipment

An attack to gain control of key terrain, personnel, or equipment is not necessarily terrain focused— a raid with the objective of taking prisoners or key equipment is also an attack to gain control. Besides the classic seizure of key terrain that dominates a battlefield, an attack to control may also target facilities such as economic targets, ports, or airfields. Tactical tasks associated with an attack to control are raid, clear, destroy, occupy, retain, secure, and seize. Some non-traditional attacks to gain control may be information attack, computer warfare, electronic warfare, or other forms of information warfare (INFOWAR).

Attack to Gain Information

An attack to gain information is a subset of the reconnaissance attack. (See Reconnaissance Attack later in this chapter.) In this case, the purpose is not to locate to destroy, fix, or occupy but rather to gain information about the enemy. Quite often the OPFOR will have to penetrate or circumvent the enemy’s security forces and conduct an attack in order to determine the enemy’s location, dispositions, capabilities, and intentions.

Attack to Dislocate

An attack to dislocate employs forces to obtain significant positional advantage, rendering the enemy’s dispositions less valuable, perhaps even irrelevant. It aims to make the enemy expose forces by reacting to the dislocating action. Dislocation requires enemy commanders to make a choice: accept neutralization of part of their force or risk its destruction while repositioning. Turning movements and envelopments produce dislocation. Artillery or other direct or indirect fires may cause an enemy to either move to a more tenable location or risk severe attrition. Typical tactical tasks associated with dislocation are ambush, interdict, and neutralize.

Attack to Disrupt

An attack to disrupt is used to prevent the enemy from being able to execute an advantageous course of action (COA) or to degrade his ability to execute that COA. It is also used to create windows of opportunity to be exploited by the OPFOR. It is an intentional interference (disruption) of enemy plans and intentions, causing the enemy confusion and the loss of focus, and throwing his battle synchronization into turmoil. The OPFOR then quickly exploits the result of the attack to disrupt. A spoiling attack is an example of an attack to disrupt.

The OPFOR will use an attack to disrupt in order to upset an enemy’s formation and tempo, interrupt the enemy’s timetable, cause the enemy to commitment of forces prematurely, and/or cause him to attack in a piecemeal fashion. The OPFOR will either attack the enemy force with enough combat power to achieve the desired results with one mass attack, or sustain the attack until the desired results are achieved.

Note. Disrupt is not only a purpose of the offense, but also a tactical task.

Attacks to disrupt typically focus on a key enemy capability, intention, or vulnerability. They are also designed to disrupt enemy plans, tempo, infrastructure, logistics, affiliations, C2, formations, or civil order. However, an attack to disrupt is not limited to any of the above. The OPFOR will use any method necessary to upset the enemy and cause disorder, disarray, and confusion.

Attacks to disrupt often have a strong INFOWAR component and may disrupt, limit, deny, and/or degrade the enemy’s use of the electromagnetic spectrum, especially the enemy’s C2. They may also take the form of computer warfare and/or information attack.

Attacks to disrupt are carried out at all levels and are limited only by time and resources available. The attack to disrupt may not be limited by distance. It may be carried out in proximity to the enemy (as in an ambush) or from an extreme distance (such as computer warfare or information attack from another continent) or both simultaneously. The attack to disrupt may be conducted by a single component (an ambush in contact) or a coordinated attack by several components such as combined arms using armored fighting vehicles, infantry, artillery, and several elements of INFOWAR (for example, electronic warfare, deception, perception management, information attack, and/or computer warfare).

The OPFOR does not limit its attacks to military targets or enemy combatants. The attack to disrupt may be carried out against noncombatant civilians (even family members of enemy soldiers at home station or in religious services), diplomats, contractors, or whomever and/or whatever the OPFOR commanders believe will enhance their probabilities of mission success.

Planning the Offense

For the OPFOR, the key elements of planning offensive missions are⎯

- Determining the objective of the offensive action.

- Defining time available to complete the action.

- Determining the level of planning possible (planned versus situational offense).

- Organizing the battlefield.

- Organizing forces and elements by function, including affiliated forces.

- Organizing INFOWAR activities in support of the offense (see chapter 7).

Planned Offense

A planned offense is an offensive mission or action undertaken when there is sufficient time and knowledge of the situation to prepare and rehearse forces for specific tasks. Typically, the enemy is in a defensive position and in a known location. Key considerations in offensive planning are⎯

- Selecting a clear and appropriate objective.

- Determining which enemy forces (security, reaction, or reserve) must be fixed.

- Developing a reconnaissance plan that locates and tracks all key enemy targets and elements.

- Creating or taking advantage of a window of opportunity to free friendly forces from any enemy advantages in precision standoff and situational awareness.

- Determine which component or components of an enemy’s combat system to attack.

Situational Offense

The OPFOR may also conduct a situational offense. It recognizes that the modern battlefield is chaotic. Fleeting opportunities to strike at an enemy weakness will continually present themselves and just as quickly disappear. Although detailed planning and preparation greatly mitigate risk, they are often not achievable if a window of opportunity is to be exploited.

The following are examples of conditions that might lead to a situational offense:

- A key enemy unit, system, or capability is exposed.

- The OPFOR has an opportunity to conduct a spoiling attack to disrupt enemy defensive preparations.

- An OPFOR unit makes contact on favorable terms for subsequent offensive action.

In a situational offense, the commander develops his assessment of the conditions rapidly and without a great deal of staff involvement. He provides a basic COA to the staff, which then quickly turns that COA into an executable combat order. Even more than other types of OPFOR offensive action, the situational offense relies on implementation of battle drills by subordinate tactical units (see chapter 5).

Organization of the battlefield in a situational offense will normally be limited to minor changes to existing control measures. The nature of situational offense is such that it often involves smaller, independent forces accomplishing discrete missions. These missions will typically require the use of task- organized tactical groups and detachments of various types.

Note. Any division or brigade receiving additional assets from a higher command becomes a division tactical group (DTG) or brigade tactical group (BTG). Therefore, references to a tactical group throughout this chapter may also apply to division or brigade, unless specifically stated otherwise.

Functional Organization of Forces for the Offense--Tactical Groups, Divisions, and Brigades

In planning and executing offensive actions, OPFOR commanders at brigade level and above organize and designate various forces within his level of command according to their function. (See chapter 2.) Thus, subordinate forces understand their roles within the overall battle. However, the organization of forces can shift dramatically during the course of a battle, if part of the plan does not work or works better than anticipated. For example, a unit that started out being part of a fixing force might split off and become an exploitation force, if the opportunity presents itself.

Each functional force has an identified commander. This is often the senior commander of the largest subordinate unit assigned to that force. For example, if two BTGs are acting as the DTG’s fixing force, the senior of the two BTG commanders is the fixing force commander. Since, in this option, each force commander is also a subordinate unit commander, he controls the force from his unit’s command post (CP). Another option is to have one of the DTG’s CPs be in charge of a functional force. For example, the forward CP could control a disruption force or a fixing force. Another possibility would be for the integrated fires command (IFC) CP to command the disruption force, the exploitation force, or any other force whose actions must be closely coordinated with fires delivered by the IFC.

In any case, the force commander is responsible to the tactical group commander to ensure that combat preparations are made properly and to take charge of the force during the battle. This frees the tactical group commander from decisions specific to the force’s mission. Even when tactical group subordinates have responsibility for parts of the disruption zone, there is still an overall tactical group disruption force commander.

A battalion or below organization can serve as a functional force (or part of one) for its higher command. At any given time, it can be part of only a single functional force or a reserve. If, for example, a BTG needed one part of one of its battalions to serve as an enabling force, but needed another part to join the exploitation force, one of the two battalion subunits would be task organized as a separate detachment.

Enabling Force(s)

Various types of enabling forces are charged with creating the conditions that allow the action force the freedom to operate. In order to create a window of opportunity for the action force to succeed, the enabling force may be required to operate at a high degree of risk and may sustain substantial casualties. However, an enabling force may not even make contact with the enemy, but instead conduct a demonstration.

Battalions and below serving as an enabling force are often required to conduct breaching or obstacle-clearing tasks, However, it is important to remember that the requirements laid on the enabling force are tied directly to the type and mission of the action force.

Disruption Force

In the offense, the disruption force would typically include the disruption force that already existed in a preceding defensive situation (see chapter 4). It is possible that forces assigned for actions in the disruption zone in the defense might not have sufficient mobility to do the same in the offense or that targets may change and require different or additional assets. Thus, the disruption force might require augmentation. For example, the disruption force for a division or DTG is typically a BTG especially task- organized for that function. Battalions and below can serve as disruption forces for brigades or BTGs. However, this mission typically is complex enough for them to be task-organized as detachments.

Fixing Force

OPFOR offensive actions are founded on the concept of fixing enemy forces so that they are not free to maneuver. The OPFOR recognizes that units and soldiers can be fixed in a variety of ways. For example⎯

- They find themselves without effective communication with higher command.

- Their picture of the battlefield is unclear.

- They are (or believe they are) decisively engaged in combat.

- They have lost mobility due to complex terrain, obstacles, or weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

In the offense, planners will identify which enemy forces need to be fixed and the method by which they will be fixed. They will then assign this responsibility to a force that has the capability to fix the required enemy forces with the correct method. The fixing force may consist of a number of units separated from each other in time and space, particularly if the enemy forces required to be fixed are likewise separated. A fixing force could consist entirely of affiliated irregular forces. It is possible that a discrete attack on logistics, command and control (C2), or other systems could fix an enemy without resorting to deploying large fixing forces.

Battalions and below often serve as fixing forces for BTGs and are also often capable of performing this mission without significant task organization. This is particularly true in those cases where simple suppressive fires are sufficient to fix enemy forces.

Assault Force

At BTG level, the commander may employ one or more assault forces. This means that one or more subordinate detachments would conduct an assault to destroy an enemy force or seize a position. However, the purpose of such an assault is to create or help create the opportunity for the action force to accomplish the BTG’s overall mission. (See the section on Assault below, under Types of Offensive Action— Detachment, Battalion, and Company.)

Security Force

The security force conducts activities to prevent or mitigate the effects of hostile actions against the overall tactical-level command and/or its key components. If the commander chooses, he may charge this security force with providing force protection for the entire area of responsibility (AOR), including the rest of the functional forces; logistics and administrative elements in the support zone; and other key installations, facilities, and resources. The security force may include various types of units⎯such as infantry, special-purpose forces (SPF), counterreconnaissance, and signals reconnaissance assets⎯to focus on enemy special operations and long-range reconnaissance forces operating throughout the AOR. It can also include Internal Security Forces units allocated to the tactical-level command, with the mission of protecting the overall command from attack by hostile insurgents, terrorists, and special operations forces. The security force may also be charged with mitigating the effects of WMD.

Deception Force

When the INFOWAR plan requires combat forces to take some action (such as a demonstration or feint), these forces will be designated as deception forces in close-hold executive summaries of the plan. Wide-distribution copies of the plan will refer to these forces according to the designation given them in the deception story.

Support Force

A support force provides support by fire; other combat or combat service support; or C2 functions for other parts of the tactical group. (When fire support units in the figures in this chapter are not identified as performing another function, they are probably acting as a support force.)

Action Force(s)

One part of the tactical group conducting a particular offensive action is normally responsible for performing the primary function or task that accomplishes the overall goal or objective of that action. In most general terms, therefore, that part can be called the action force. In most cases, however, the tactical group commander will give the action force a more specific designation that identifies the specific function it is intended to perform, which equates to achieving the objective of the tactical group’s mission.

There are three basic types of action forces: exploitation force, strike force, and mission force. In some cases there may be more than one such force.

Exploitation Force

In most types of offensive action at tactical group level, an exploitation force is assigned the task of achieving the objective of the mission. It typically exploits a window of opportunity created by an enabling force. In some situations, the exploitation force could engage the ultimate objective with fires only.

Strike Force

A strike is an offensive COA that rapidly destroys a key enemy organization through a synergistic combination of massed precision fires and maneuver. The primary objective of a strike is the enemy’s will and ability to fight. A strike is typically planned and coordinated at the operational level. However, it is often executed by a tactical-level force. The force that actually accomplishes the final destruction of the targeted enemy force is called the strike force. (See FM 7-100.1 for more detailed discussion of a strike.)

Mission Force

In those non-strike offensive actions where the mission can be accomplished without the creation of a specific window of opportunity, the set of capabilities that accomplish the mission are collectively known as a mission force. However, the tactical group commander may give a mission force a more specific designation that identifies its specific function.

Reserves

OPFOR offensive reserve formations will be given priorities in terms of whether the staff thinks it most likely that they will act as a particular type of enabling or action force. The size and composition of an offensive reserve are entirely situation-dependent.

Functional Organization of Elements for the Offense--Detachments, Battalions, and Below

An OPFOR detachment is a battalion or company designated to perform a specific mission and task- organized to do so. Commanders of detachments, battalions, and companies organize their subordinate units according to the specific functions they intend each subordinate to perform. They use a methodology of “functional organization” similar to that used by used by brigades and above (see chapter 2). However, one difference is that commanders at brigade and higher use the term forces when designating functions within their organization. Commanders at detachment, battalion, and below use the term element. Elements can be broken down into two very broad categories: action and enabling. However, commanders normally designate functional elements more specifically, identifying the specific action or the specific means of accomplishing the function during a particular mission. Commanders may also organize various types of specialist elements. Depending on the mission and conditions, there may be more than one of some of these specific element types.

Note. A detachment as a whole can receive a specific mission assigned by a higher commander. That commander gives the detachment a functional designation based on the role it will play in his overall mission or the specific function it will perform for him. For example, a detachment assigned to conduct a raid may be called the raiding detachment or the raiding force of the higher command.

The number of functional elements is unlimited and is determined by any number of variables, such as the size of the overall organization, its mission, and its target. Quite often the distinction between exactly which element is an action element or an enabling element is blurred because, as the mission progresses, conditions change or evolve and require adaptation.

Action Elements

The action element is the element conducting the primary action of the overall organization’s mission. However, the commander normally gives this element a functional designation that more specifically describes exactly what activity the element is performing on the battlefield at that particular time. For example, the action element in a raid may be called the raiding element. If an element accomplishes the objective of the mission by exploiting an opportunity created by another element, is may be called the exploitation element. Throughout this TC, the clearest and most descriptive term will be used to avoid any confusion.

At a different time or place on the battlefield, the element performing the “primary action” might have a completely different function and would be labeled accordingly. These are not permanent labels and differ with specific functions performed.

Enabling Elements

Enabling elements can enable the primary action in various ways. The most common types are security elements and support elements. The security element provides local tactical security for the overall organization and prevents the enemy from influencing mission accomplishment. (A security element providing front, flank, or rear security may be identified more specifically as the “front security element,” “flank security element,” or “rear security element.”) The support element provides combat and combat service support and C2 for the larger organization. Due to such considerations as multiple avenues of approach, a commander may organize one or more of each of these elements in specific cases.

Specialist Elements

In certain situations, a detachment may organize one or more specialist elements. Specialist elements are typically formed around a unit with a specific capability, such as an obstacle-clearing, reconnaissance, or deception. Detachments formed around such specialist elements may or may not have a security or support element depending on their specialty, their location on the battlefield, and the support received from other units. For example, a movement support detachment (MSD) typically has a reconnaissance and obstacle-clearing element, plus one or two road and bridge construction and repair elements. If an MSD is receiving both security and other support from the infantry or mechanized units preparing to move through the cleared and prepared area, it probably will not have its own support and security elements. In this case, all of the elements will be dedicated to various types of engineer mobility functions.

Preparing for the Offense

In the preparation phase, the OPFOR focuses on ways of applying all available resources and the full range of actions to place the enemy in the weakest condition and position possible. Commanders prepare their organizations for all subsequent phases of the offense. They organize the battlefield and their forces and elements with an eye toward capitalizing on conditions created by successful attacks.

Establish Contact

The number one priority for all offensive actions is to gain and maintain contact with key enemy forces. As part of the decision making process, the commander and staff identify which forces must be kept under watch at all times. The OPFOR will employ whatever technical sensors it has at its disposal to locate and track enemy forces, but the method of choice is ground reconnaissance. It may also receive information on the enemy from the civilian populace, local police, or affiliated irregular forces.

Make Thorough Logistics Arrangements

The OPFOR understands that there is as much chance of an offense being brought to culmination by a lack of sufficient logistics support as by enemy action. Careful consideration will be given to carried days of supply and advanced caches to obviate the need for easily disrupted lines of communications (LOCs).

Modify the Plan When Necessary

The OPFOR takes into account that, while it might consider itself to be in the preparation phase for one battle, it is continuously in the execution phase. Plans are never considered final. Plans are checked throughout the course of their development to ensure they are still valid in light of battlefield events.

Rehearse Critical Actions in Priority

The commander establishes the priority for the critical actions expected to take place during the battle. The force rehearses those actions in as realistic a manner as possible for the remainder of the preparation time.

Executing the Offense

The degree of preparation often determines the nature of the offense in the execution phase. Successful execution depends on forces that understand their roles in the battle and can swiftly follow preparatory actions with the maximum possible shock and violence and deny the enemy any opportunity to recover. A successful execution phase often ends with transition to the defense in order to consolidate gains, defeat enemy counterattacks, or avoid culmination. In some cases, the execution phase is followed by continued offensive action to exploit opportunities created by the battle just completed.

Maintain Contact

The OPFOR will go to great lengths to ensure that its forces maintain contact with key elements of the enemy force throughout the battle. This includes rapid reconstitution of reconnaissance assets and units and the use of whatever combat power is necessary to ensure success.

Implement Battle Drills

The OPFOR derives great flexibility from battle drills. (See chapter 5 for more detail.) Contrary to the U.S. view that battle drills, especially at higher levels, reduce flexibility, the OPFOR uses minor, simple, and clear modifications to thoroughly understood and practiced battle drills to adapt to ever- shifting conditions. It does not write standard procedures into its combat orders and does not write new orders when a simple shift from current formations and organization will do. OPFOR offensive battle drills will include, but not be limited to, the following:

- React to all seven forms of contact⎯direct fire, indirect fire, visual, obstacle, CBRN, electronic warfare, and air attack.

- Fire and maneuver.

- Fixing enemy forces.

- Situational breaching.

Modify the Plan When Necessary

The OPFOR is sensitive to the effects of mission dynamics and realizes that the enemy’s actions may well make an OPFOR unit’s original mission achievable, but completely irrelevant. As an example, a unit of the fixing force in an attack may be keeping its portion of the enemy force tied down while another portion of the enemy force is maneuvering nearby to stop the exploitation force. In this case, the OPFOR unit in question must be ready to transition to a new mission quickly and break contact to fix the maneuvering enemy force.

Seize Opportunities

The OPFOR places maximum emphasis on decentralized execution, initiative, and adaptation. Subordinate units are expected to take advantage of fleeting opportunities so long as their actions are in concert with the goals of the higher command.

Dominate the Tempo of Combat

Through all actions possible, the OPFOR plans to control the tempo of combat. It will use continuous attack, INFOWAR, and shifting targets, objectives, and axes to ensure that tactical events are taking place at the pace it desires.

Types of Offensive Action--Tactical Groups, Divisions, and Brigades

The types of offensive action in OPFOR doctrine are both tactical methods and guides to the design of COAs. An offensive mission may include subordinate units that are executing different offensive and defensive COAs within the overall offensive mission framework.

Note. Any division or brigade receiving additional assets from a higher command becomes a division tactical group (DTG) or brigade tactical group (BTG). Therefore, references to a tactical group throughout this chapter may also apply to division or brigade, unless specifically stated otherwise.

Attack

An attack is an offensive operation that destroys or defeats enemy forces, seizes and secures terrain, or both. It seeks to achieve tactical decision through primarily military means by defeating the enemy’s military power. This defeat does not come through the destruction of armored weapons systems but through the disruption, dislocation, and subsequent paralysis that occurs when combat forces are rendered irrelevant by the loss of the capability or will to continue the fight. Attack is the method of choice for OPFOR offensive action. There are two types of attack: integrated attack and dispersed attack.

The OPFOR does not have a separate design for “exploitation” as a distinct offensive COA. Exploitation is considered a central part of all integrated and dispersed attacks.

The OPFOR does not have a separate design for “pursuit” as a distinct offensive COA. A pursuit is conducted using the same basic COA framework as any other integrated or dispersed attack. The fixing force gains contact with the fleeing enemy force and slows it or forces it to stop while the assault and exploitation forces create the conditions for and complete the destruction of the enemy’s C2 and logistics structure or other systems.

The OPFOR recognizes that moving forces that make contact must rapidly choose and implement an offensive or defensive COA. The OPFOR methodology for accomplishing this is discussed in chapter 5.

Integrated Attack

Integrated attack is an offensive action where the OPFOR seeks military decision by destroying the enemy’s will and/or ability to continue fighting through the application of combined arms effects. Integrated attack is often employed when the OPFOR enjoys overmatch with respect to its opponent and is able to bring all elements of offensive combat power to bear. It may also be employed against a more sophisticated and capable opponent, if the appropriate window of opportunity is created or available. See figures 3-1 through 3-3 for examples of integrated attacks.

The primary objective of an integrated attack is destroying the enemy’s will and ability to fight. The OPFOR recognizes that modern militaries cannot continue without adequate logistics support and no military, modern or otherwise, can function without effective command and control.

Integrated attacks are characterized by⎯

- Not being focused solely on destruction of ground combat power but often on C2 and logistics.

- Fixing the majority of the enemy’s force in place with the minimum force necessary.

- Isolating the targeted subcomponent(s) of the enemy’s combat system from his main combat power.

- Using complex terrain to force the enemy to fight at a disadvantage.

- Using deception and other components of INFOWAR to degrade the enemy’s situational understanding and ability to target OPFOR formations.

- Using flank attack and envelopment, particularly of enemy forces that have been fixed.

The OPFOR prefers to conduct integrated attacks when most or all of the following conditions exist:

- The OPFOR possesses significant overmatch in combat power over enemy forces.

- It possesses at least air parity over the critical portions of the battlefield.

- It is sufficiently free of enemy standoff reconnaissance and attack systems to be able to operate without accepting high levels of risk.

Functional Organization for an Integrated Attack

An integrated attack employs various types of functional forces. The tactical group commander assigns subordinate units functional designations that correspond to their intended roles in the attack.

Enabling Forces

An integrated attack often employs fixing, assault, and support forces. A disruption force exists, but is not created specifically for this type of offensive action.

Fixing Force. The fixing force in an integrated attack is required to prevent enemy defending forces, reserves, and quick-response forces from interfering with the actions of the assault and exploitation forces. The battle will develop rapidly, and enemy forces not in the attack zone cannot be allowed to reposition to influence the assault and exploitation forces. Maneuver forces, precision fires, air defense units, long-range antiarmor systems, situational obstacles, chemical weapons, and electronic warfare are well suited to fix defending forces.

Assault Force. At BTG level, the commander may employ one or more assault forces. The assault force in an integrated attack is charged with destroying a particular part of the enemy force or seizing key positions. Such an assault can create a window of opportunity for an exploitation force. An assault force may successfully employ infiltration of infantry to carefully pre-selected points to assist the exploitation force in its penetration of enemy defenses.

Support Force. A support force provides support to the attack by fire; other combat or combat service support; or C2 functions. Smoke and suppressive artillery and rocket fires, combat engineer units, and air-delivered weapons are well suited to this function.

Action Force

The most common type of action force in an integrated attack is the exploitation force. Such a force must be capable of penetrating or avoiding enemy defensive forces and attacking and destroying the enemy’s support infrastructure before he has time to react. An exploitation force ideally possesses a combination of mobility, protection, and firepower that permits it to reach the target with sufficient combat power to accomplish the mission.

Dispersed Attack

Dispersed attack is the primary manner in which the OPFOR conducts offensive action when threatened by a superior enemy and/or when unable to mass or provide integrated C2 to an attack. This is not to say that the dispersed attack cannot or should not be used against peer forces, but as a rule integrated attack will more completely attain objectives in such situations. Dispersed attack relies on INFOWAR and dispersion of forces to permit the OPFOR to conduct tactical offensive actions while overmatched by precision standoff weapons and imagery and signals sensors. The dispersed attack is continuous and comes from multiple directions. It employs multiple means working together in a very interdependent way. The attack can be dispersed in time as well as space. See figures 3-4 through 3-6 on pages, 3-14 through 3-16 for examples of dispersed attacks.

The primary objective of dispersed attack is to take advantage of a window of opportunity to bring enough combined arms force to bear to destroy the enemy’s will and/or capability to continue fighting. To achieve this, the OPFOR does not necessarily have to destroy the entire enemy force, but often just destroy or degrade a key component of the enemy’s combat system.

Selecting the appropriate component of the enemy’s combat system to destroy or degrade is the first step in planning the dispersed attack. This component is chosen because of its importance to the enemy and varies depending on the force involved and the current military situation. For example, an enemy force dependent on one geographical point for all of its logistics support and reinforcement would be most vulnerable at that point. Disrupting this activity at the right time and to the right extent may bring about tactical decision on the current battlefield, or it may open further windows of opportunity to attack the enemy’s weakened forces at little cost to the OPFOR. In another example, an enemy force preparing to attack may be disrupted by an OPFOR attack whose purpose is to destroy long-range missile artillery, creating the opportunity for the OPFOR to achieve standoff with its own missile weapons. In a final example, the key component chosen may be the personnel of the enemy force. Attacking and causing mass casualties among infantrymen may delay an enemy offensive in complex terrain while also being politically unacceptable for the enemy command structure.

Dispersed attacks are characterized by⎯

- Not being focused on complete destruction of ground combat power but rather on destroying or degrading a key component of the enemy’s combat system (often targeting enemy C2 and logistics).

- Fixing and isolating enemy combat power.

- Using smaller, independent subordinate elements.

- Conducting rapid moves from dispersed locations.

- Massing at the last possible moment.

- Conducting simultaneous attack at multiple, dispersed locations.

- Using deception and other elements of INFOWAR to degrade the enemy’s situational understanding and ability to target OPFOR formations.

The window of opportunity needed to establish conditions favorable to the execution of a dispersed attack may be one created by the OPFOR or one that develops due to external factors in the operational environment. When this window must be created, the OPFOR keys on several tasks that must be accomplished:

- Destroy enemy ground reconnaissance.

- Deceive enemy imagery and signals sensors.

- Create an uncertain air defense environment.

- Selectively deny situational awareness.

- Maximize use of complex terrain.

Functional Organization for a Dispersed Attack

A dispersed attack employs various types of functional forces. The tactical group commander assigns subordinate units functional designations that correspond to their intended roles in the attack.

Enabling Forces

A dispersed attack often employs fixing, assault, and support forces. A disruption force exists, but is not created specifically for this type of offensive action. Deception forces can also play an important role in a dispersed attack.

Fixing Force. The fixing force in a dispersed attack is primarily focused on fixing enemy response forces. Enemy reserves, quick response forces, and precision fire systems that can reorient rapidly will be those elements most capable of disrupting a dispersed attack. Maneuver forces, precision fires, air defense and antiarmor ambushes, situational obstacles, chemical weapons, and electronic warfare are well suited to fix these kinds of units and systems. Dispersed attacks often make use of multiple fixing forces separated in time and/or space.

Assault Force. At BTG level, the commander may employ one or more assault forces. The assault force in an integrated attack is charged with destroying a particular part of the enemy force or seizing key positions. Such an assault can create favorable conditions for the exploitation force to rapidly move from dispersed locations and penetrate or infiltrate enemy defenses. An assault force may successfully employ infiltration of infantry to carefully pre-selected points to assist the exploitation force in its penetration. Dispersed attacks often make use of multiple assault forces separated in time and/or space.

Support Force. A support force provides support to the attack by fire; other combat or combat service support; or C2 functions. Smoke and suppressive artillery and rocket fires, combat engineer units, and air-delivered weapons are well suited to this function.

Action Forces

The most common type of action force in an integrated attack is the exploitation force. Such a force must be capable, through inherent capabilities or positioning relative to the enemy, of destroying the target of the attack. In one set of circumstances, a tank brigade may be the unit of choice to maneuver throughout the battlefield as single platoons in order to have one company reach a vulnerable troop concentration or soft C2 node. Alternatively, the exploitation force may be a widely dispersed group of SPF teams set to attack simultaneously at exposed logistics targets. Dispersed attacks often make use of multiple exploitation forces separated in time and/or space, but often oriented on the same objective or objectives.

Note. The example of a dispersed attack by a BTG in figure 3-6 would unfold in the following sequence. The disruption force—consisting primarily of SPF teams and a UAV company (shown at its launch and recovery position)—locates and destroys enemy reconnaissance. Fixing forces 1, 2, and 3—consisting primarily of mechanized battalion-size detachments (BDETs)— ensure that the enemy combat battalions and brigade reserve do not have freedom to maneuver. Support forces 1 and 2—consisting primarily of artillery and antitank weapons—provide direct and indirect fires that assist the fixing forces. With all enemy combat forces fixed, exploitation forces 1, 2, and 3—consisting of guerillas, insurgents, INFOWAR, and combined arms forces— destroy the enemy C2 and logistics structure.

Limited-Objective Attack

A limited-objective attack seeks to achieve results critical to the battle plan or even the operation plan by destroying or denying the enemy key capabilities through primarily military means. The results of a limited-objective attack typically fall short of tactical or operational decision on the day of battle, but may be vital to the overall success of the battle or operation. Limited-objective attacks are common while fighting a stronger enemy with the objective of preserving forces and wearing down the enemy, rather than achieving decision.

The primary objective of a limited-objective attack is a particular enemy capability. This may or may not be a particular man-made system or group of systems, but may also be the capability to take action at the enemy’s chosen tempo.

Limited-objective attacks are characterized by⎯

- Not being focused solely on destruction of ground combat power but often on C2 and logistics.

- Denying the enemy the capability he most needs to execute his plans.

- Maximal use of the systems warfare approach to combat (see chapter 1).

- Significant reliance on a planned or seized window of opportunity.

Quite often, the limited-objective attack develops as a situational offense. This occurs when an unclear picture of enemy dispositions suddenly clarifies to some extent and the commander wishes to take advantage of the knowledge he has gained to disrupt enemy timing. This means that limited-objective attacks are often conducted by reserve or response forces that can rapidly shift from their current posture to strike at the enemy.

There are two types of tactical limited-objective attack: spoiling attack and counterattack. These share some common characteristics, but differ in purpose.

Spoiling Attack

The purpose of a spoiling attack is to preempt or seriously impair an enemy attack while the enemy is in the process of planning, forming, assembling, or preparing to attack. It is designed to control the tempo of combat by disrupting the timing of enemy operations. The spoiling attack is a type of attack to disrupt.

Spoiling attacks do not have to accomplish a great deal to be successful. Conversely, planners must focus carefully on what effect the attack is trying to achieve and how the attack will achieve that effect. In some cases, the purpose of the attack will be to remove a key component of the enemy’s combat system. A successful spoiling attack can make this key component unavailable for the planned attack and therefore reduces the enemy’s overall chances of success. More typically, the attack is designed to slow the development of conditions favorable to the enemy’s planned attack. See figure 3-7 on page 3-18 for an example of a spoiling attack.

Spoiling attacks are characterized by⎯

- A requirement to have a clear picture of enemy preparations and dispositions.

- Independent, small unit action.

- Highly focused objectives.

- The possibility that a spoiling attack may open a window of opportunity for other combat actions.

The OPFOR seeks to have the following conditions met in order to conduct a spoiling attack:

- Reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) establishes a picture of enemy attack preparations.

- Enemy security, reserve, and response forces are located and tracked.

- Enemy ground reconnaissance in the attack zone is destroyed or rendered ineffective.

Functional Organization for a Spoiling Attack

A spoiling attack may or may not involve the use of enabling forces. If enabling forces are required, the part of the tactical group that actually executes the spoiling attack would be an exploitation force. Otherwise, it may be called the mission force. The exploitation or mission force will come from a part of the tactical group that is capable of acting quickly and independently to take advantage of a fleeting opportunity. Since the spoiling attack is a type of attack to disrupt, the exploitation or mission force might come from the disruption force. If more combat power is required, it might come from the main defense force, which would not yet be engaged. A third possibility is that it could come from the tactical group reserve.

Counterattack

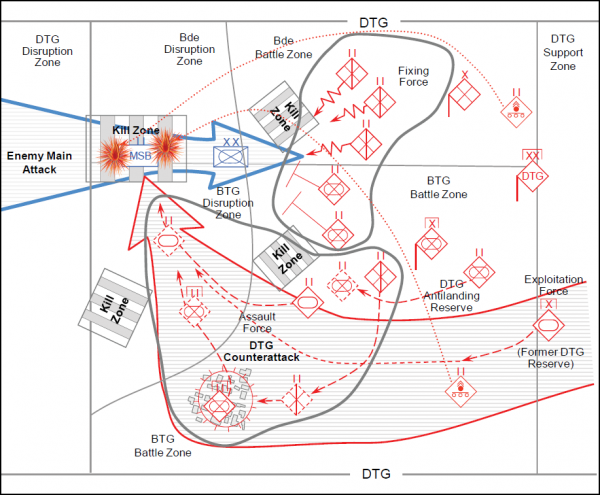

A counterattack is a form of attack by part or all of a defending force against an enemy attacking force with the general objective of denying the enemy his goal in attacking. It is designed to cause an enemy offensive operation to culminate and allow the OPFOR to return to the offense. A counterattack is designed to control the tempo of combat by returning the initiative to the OPFOR. See figure 3-8 for an example of a counterattack.

Counterattacks are characterized by⎯

- A shifting in command and support relationships to assume an offensive posture for the counterattacking force.

- A proper identification that the enemy is at or near culmination.

- The planned rapid transition of the remainder of the force to the offense.

- The possibility that a counterattack may open a window of opportunity for other combat actions.

The OPFOR seeks to set the following conditions for a counterattack:

- Locate and track enemy reserve forces and cause them to be committed.

- Destroy enemy reconnaissance forces that could observe counterattack preparations.

Functional Organization for a Counterattack

Functional organization for a counterattack involves many of the same types of forces as for an integrated or dispersed attack. However, the exact nature of their functions may differ due to the fact that the counterattack comes out of a defensive posture. (To a large degree, functional organization of forces is the same for spoiling attacks and counterattacks. That is because both types of limited-objective attack are carried out under similar conditions.)

Enabling Forces

A counterattack often employs fixing, assault, and support forces. The disruption force was generally part of a previous OPFOR defensive posture.

Fixing Force. The fixing force in a counterattack is that part of the force engaged in defensive action with the enemy. These forces continue to fight from their current positions and seek to account for the key parts of the enemy array and ensure they are not able to break contact and reposition. Additionally, the fixing force has the mission of making contact with and destroying enemy reconnaissance forces and any combat forces that may have penetrated the OPFOR defense.

Assault Force. In a counterattack, the assault force (if one is used) is often assigned the mission of forcing the enemy to commit his reserve so that the enemy commander has no further mobile forces with which to react. If the fixing force has already forced this commitment, the counterattack design may forego the creation of an assault force.

Support Force. A support force can provide support to a counterattack by fire; other combat or combat service support; or C2 functions. Due to the time-sensitive and highly mobile nature of the counterattack, fire support may be the most critical.

Action Forces

The most common type of action force in a counterattack is an exploitation force. A larger-scale counterattack may involve more than one exploitation force.

The exploitation force in a counterattack bypasses engaged enemy forces to attack and destroy the enemy’s support infrastructure before he has time or freedom to react. An exploitation force ideally possesses a combination of mobility, protection, and firepower that permits it to reach the target with sufficient combat power to accomplish the mission.

Tactical Offensive Actions--Detachments, Battalions, and Below

OPFOR commanders of detachments, battalions, and below select the offensive action best suited to accomplishing their mission. Units at this level typically are called upon to execute one combat mission at a time. Therefore, it would be rare for such a unit to employ more than one type of offensive action simultaneously. At the tactical level, all OPFOR units, organizations, elements, and even plans are dynamic and adapt very quickly to the situation.

Note. Any battalion or company receiving additional assets from a higher command becomes a battalion-size detachment (BDET) or company-size detachment (CDET). Therefore, references to a detachment throughout this chapter may also apply to battalion or company, unless specifically stated otherwise.

Assault

An assault is an attack that destroys an enemy force through firepower and the physical occupation and/or destruction of his position. An assault is the basic form of OPFOR tactical offensive combat. Therefore, other types of offensive action may include an element that conducts an assault to complete the mission; however, that element will typically be given a designation that corresponds to the specific mission accomplished. (For example, an element that conducts an assault in the completion of an ambush would be called the ambush element.)

The OPFOR does not have a separate design for “mounted” and “dismounted” assaults, since the same basic principles apply to any assault action. An assault may have to make use of whatever units can take advantage of a window of opportunity, but the OPFOR views all assaults as combined arms actions. See figures 3-9 through 3-11 on pages 3-21 through 3-23 for examples of assault.

Functional Organization for an Assault

A detachment conducting an ambush typically is organized into three elements: the assault element, the security element, and the support element.

Assault Element

The assault element is the action element. It maneuvers to and seizes the enemy position, destroying any forces there.

Security Element

The security element provides early warning of approaching enemy forces and prevents them from reinforcing the assaulted unit. Security elements often make use of terrain choke points, obstacles, ambushes and other techniques to resist larger forces for the duration of the assault. The commander may (or may be forced to) accept risk and employ a security element that can only provide early warning but is not strong enough to halt or repel enemy reinforcements. This decision is based on the specific situation.

Support Element

The support element provides the assaulting detachment with one or more of the following:

- C2.

- Combat service support (CSS).

- Supporting direct fire (such as small arms, grenade launchers, or infantry antitank weapons).

- Supporting indirect fire (such as mortars or artillery).

- Mobility support.

Organizing the Battlefield for an Assault

The detachment conducting an assault is given an AOR in which to operate. A key decision with respect to the AOR will be whether or not a higher headquarters is controlling the airspace associated with the assault.

The combat order, which assigns the AOR, will often identify the enemy position being assaulted as the primary objective, with associated attack routes and/or axes. Support by fire positions will typically be assigned for use by the support element. The security element will have battle positions that overwatch key enemy air and ground avenues of approach with covered and concealed routes to and from those positions.

Executing an Assault

An assault is the most violent COA a military force can undertake. The nature of an assault demands an integrated combined-arms approach. Indeed, a simple direct assault has a very low chance of success without some significant mitigating factors. Decisive OPFOR assaults are characterized by—

- Isolation of the objective (enemy position) so that it cannot be reinforced during the battle.

- Effective tactical security.

- Effective suppression of the enemy force to permit the assault element to move against the enemy position without receiving destructive fire.

- Violent fire and maneuver against the enemy.

Assault Element

The assault element must be able to maneuver from its assault position to the objective and destroy the enemy located there. It can conduct attack by fire, but this is not an optimal methodology and should only be used when necessary. Typical tactical tasks expected of the assault element are—

- Clear.

- Destroy.

- Occupy.

- Secure.

- Seize.

Speed of execution is critical to an assault. At a minimum, the assault element must move with all practical speed once it has left its attack position. However, the OPFOR goal in an assault is for all the elements to execute their tasks with as much speed as can be achieved. For example, the longer the security element takes to move to its positions and isolate the objective, the more time the enemy has to react even before the assault element has begun maneuvering. Therefore, the OPFOR prefers as much of the action of the three elements of an assault to be simultaneous as possible. OPFOR small units practice the assault continually and have clear battle drills for all of the key tasks required in an assault.

In addition to speed, the assault element will use surprise; limited visibility; complex terrain; and/or camouflage, concealment, cover, and deception (C3D). These can allow the assault element to achieve the mission while remaining combat effective. The OPFOR intent is to maintain lethal velocity in the assault by using the synergistic effects of any or all methods and/or options available.

Security Element

The security element is typically the first element to act in an assault. The security element moves to a position (or positions) where it can deny the enemy freedom of movement along any ground or air avenues of approach that can reinforce the objective or interfere with the mission of the assault element. The security element is equipped and organized such that it can detect enemy forces and prevent them from contacting the rest of the detachment. The security element normally is assigned a screen, guard, or cover task, but may also be called upon to perform other tactical tasks in support of its purpose:

- Ambush.

- Block.

- Canalize.

- Contain.

- Delay.

- Destroy.

- Disrupt.

- Fix.

- Interdict.

- Isolate

Support Element

The support element can have a wide range of functions in an assault. Typically the detachment commander exercises C2 from within a part of the support element, unless his analysis deems success requires he leads the assault element personally. The support element controls all combat support (CS) and CSS functions as well as any supporting fires. The support element typically does not become decisively engaged but parts of it may employ direct suppressive fires. Tasks typically expected of support elements in the assault are—

- Attack by fire.

- Disrupt.

- Fix.

- Neutralize.

- Support by fire.

- Canalize.

- Contain.

Command and Control of an Assault

Typically, the commander positions himself with the support element and the deputy commander moves with the assault element, although this may be reversed. The primary function of control of the assault is to arrange units and tasks in time and space so that the assault element begins movement with all capabilities of the support element brought to bear, the security element providing the detachment’s freedom to operate and the objective isolated.

Assaults in Complex Terrain

Fighting in complex terrain slows the rate of advance, requiring a high consumption of manpower and materiel, especially ammunition. In the offense, combat in cities is avoided whenever possible, either by bypassing defended localities or by seizing towns from the march before the enemy can erect defenses. When there is no alternative, units reorganize their combat formations to attack an urban area by assault. The attackers can exploit undefended towns by using them as avenues of approach or assembly areas. For fighting in urban areas, the OPFOR prefers to establish urban detachments. See chapter 6 for additional information on urban detachments, their composition, and how they fight.

Note. Complex terrain is a topographical area consisting of an urban center larger than a village and/or of two or more types of restrictive terrain or environmental conditions occupying the same space. (Restrictive terrain or environmental conditions include, but are not limited to, slope, high altitude, forestation, severe weather, and urbanization.)

The burden of combat in cities usually falls on infantry troops, supported by other arms. Tank units can be used to seal off pockets of resistance en route to the town or city, to envelop and cut off the city, or to provide reinforcements or mobile reserves for mechanized infantry units.

Complex terrain has both advantages and disadvantages for assaulting troops. Due to its unique combination of restrictive terrain and environmental conditions, complex terrain imposes significant limitations on observation, maneuver, fires, and intelligence collection. It reduces engagement ranges, thereby easing the task of keeping the assault element protected during its approach to the objective. However, it also provides the enemy cover and concealment on the objective as well as natural obstacles to movement and good ambush positions along that same approach. This is especially the case when the enemy is defending in an urban area.

Assaults in close, mixed or open terrain always face the possibility of obstacles restricting movement to the objective. Obstacles in complex terrain—man-made or not—are virtually a certainty. Typically then, assault detachments include a specialist element designed to execute mobility and/or shaping tasks in support of the assault element. This element, made up of sappers and other supporting arms, may be known as an obstacle-clearing element. Its functions would be similar to those of reconnaissance and obstacle-clearing element in a movement support detachment (see chapter 12).

Support of the Assault

An assault typically requires several types of support. These can include reconnaissance, fire support, air defense, and INFOWAR.

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance effort in support of an assault can begin long before the assault is executed. A higher level of command may control this effort, or it may allocate additional reconnaissance assets to a detachment. However, the unit conducting an assault often has to rely on its own reconnaissance effort to a large degree in order to take advantage of a window of opportunity to execute an assault. Reconnaissance patrols in support of an assault are typically given the following missions:

- Determine and observe enemy reinforcement and counterattack routes.

- Determine composition and disposition of the forces on the objective.

- Locate and mark enemy countermobility and survivability effort.

- Locate and track enemy response forces.

- Defeat enemy C3D effort.

Fire Support

The primary mission of fire support in an assault is to suppress the objective and protect the advance of the assault element. Precision munitions may be used to destroy key systems that threaten the assault force and prevent effective reinforcement of the objective. Fire support assets committed to the assault are typically part of the support element.

Air Defense

The typical purpose of air defense support to an assault is to prevent enemy air power from influencing the action of the assault element. It is possible to find air defense systems and measures in all three elements of an assault.

Air defense systems in the security element provide early warning and defeat enemy aerial response to the assault. Such systems also target enemy aerial reconnaissance such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to prevent the enemy from having a clear picture of the assault action. Air defense systems in the support element provide overwatch of the assault element and the objective.

Air defense systems are least likely to be found in the assault element. However, such situations as long attack axes, which require the assault force to operate out of the range of systems in the support element for any length of time, may dictate this disposition of air defense systems.

Some air defense systems may prove useful in close combat such as urban areas. Air defense weapons usually have a very high angle of fire allowing them to target the upper stories of buildings. High- explosive rounds allow the weapons to shoot through the bottom floor of the top story, successfully engaging enemy troops and/or equipment located on roof tops. The accuracy and lethality of air defense weapons also facilitates their role as a devastating ground weapon when used against personnel, equipment, buildings, and lightly armored vehicles.

INFOWAR

INFOWAR supports the assault primarily by helping isolate the objective. This is often done by—

- Deceiving forces at the objective as to the timing, location, and/or intent of the assault.

- Conducting deception operations to fix response forces.

- Isolating the objective with electronic warfare.

Note: A simple, effective, and successful technique often employed by the OPFOR is to distract and then flank with multiple coordinated assaults.

Ambush

An ambush is a surprise attack from a concealed position, used against moving or temporarily halted targets. Such targets could include truck convoys, railway trains, boats, individual vehicles, or dismounted troops. In an ambush, enemy action determines the time, and the OPFOR sets the place. Ambushes may be conducted to—

- Destroy or capture personnel and supplies.

- Harass and demoralize the enemy.

- Delay or block movement of personnel and supplies.

- Canalize enemy movement by making certain routes useless for traffic.

The OPFOR also uses ambush as a primary psychological warfare tool. The psychological effect is magnified by the OPFOR use of multi-tiered ambushes. A common tactic is to spring an ambush and set other ambushes along the relief or reaction force’s likely avenues of approach. (For an example, see figure 3-17 on page 3-34.) Another tactic is to attack enemy medical evacuation assets, especially if the number of these assets is limited. The destruction of means to evacuate wounded instills a sense of tentativeness in the enemy soldiers because they realize that, should they become wounded or injured, medical help will not be forthcoming.

Note: Prior to springing an ambush, the OPFOR may prefer to wait until enemy sweep operations end. As enemy units return to garrison, tired, low on fuel, and lax after searching for an extended time and not engaging, the OPFOR strikes hard.

Cutting LOCs is a basic OPFOR tactic. The OPFOR attempts to avoid enemy maneuver units and concentrate on ambushes along supporting LOCs. Attacking LOCs damages an enemy’s economic infrastructure, isolates military units, and attrits the enemy with little risk to the ambush force. Successful ambushes usually result in concentrating the majority of movements to principal roads, railroads, or waterways where targets are more vulnerable to attack by other forces.

Key factors in an ambush are—

- Surprise.

- Control.

- Coordinated fires and shock (timing).

- Simplicity.

- Discipline.

- Security (and enemy secondary reaction).

- Withdrawal.

Functional Organization for an Ambush

Similar to an assault, a detachment conducting an ambush is typically organized into three elements: the ambush element, the security element, and the support element. There may be more than one of each of these types of element.

Ambush Element

The ambush element of an ambush has the mission of attacking and destroying enemy elements in the kill zone(s). The ambush element conducts the main attack against the ambush target that includes halting the column, killing or capturing personnel, recovering supplies and equipment, and destroying unwanted vehicles or supplies that cannot be moved.

Security Element

The security element of an ambush has the mission to prevent enemy elements from responding to the ambush before the main action is concluded. Failing that, it prevents the ambush element from becoming decisively engaged. This is often accomplished simply by providing early warning.

Security elements are placed on roads and trails leading to the ambush site to warn the ambush element of the enemy approach. These elements isolate the ambush site using roadblocks, other ambushes, and outposts. They also assist in covering the withdrawal of the ambush element from the ambush site. The distance between the security element and the ambush element is dictated by terrain. In many instances, it may be necessary to organize secondary ambushes and roadblocks to intercept and delay enemy reinforcements.

Support Element

The support element of an ambush has the same basic functions as that of an assault. It is quite often involved in supporting the ambush element with direct and/or indirect fires.

Planning and Preparation for an Ambush

The planning and preparation of an ambush is similar that for a raid, except that selecting an ambush site is an additional consideration. A detachment is typically assigned a battle zone in which to execute an ambush, since such attacks typically do not require control of airspace at the detachment level. The area where the enemy force is to be destroyed is delineated by one or more kill zones.

The mission may be a single ambush against one target or a series of ambushes against targets on one or more LOCs. The probable size, strength, and composition of the enemy force that is to be ambushed, formations the enemy is likely to use, and enemy reinforcement capabilities are considered. Favorable terrain for an ambush, providing unobserved routes for approach and withdrawal, must be selected.

The time of the ambush should coincide with periods of limited visibility, offering a wider choice of positions and better opportunities to surprise and confuse the enemy. However, movement and control are more difficult during a night ambush. Night ambushes are more suitable when the mission can be accomplished during, or immediately following, the initial burst of fire. They require a maximum number of automatic weapons to be used at close range. Night ambushes can hinder the enemy’s use of LOCs at night, while friendly aircraft can attack the same routes during the day (if the enemy does not have air superiority). Daylight ambushes facilitate control and permit offensive action for a longer period of time. Daylight ambushes also provide an opportunity for more effective fire from such weapons as rocket launchers and antiarmor weapons.

Site Selection

In selecting the ambush site, the basic consideration is favorable terrain, although limitations such as deficiencies in firepower and lack of resupply during actions may govern the choice of the ambush site. The site should have firing positions offering concealment and favorable fields of fire. Whenever possible, firing should be conducted from the screen of foliage. The terrain at the site should serve to canalize the enemy into a kill zone. The entire kill zone is covered by fire so that there is no dead space that would allow the enemy to organize resistance. The ambush force should take advantage of natural obstacles such as defiles, swamps, and cliffs to restrict enemy maneuvers against the force. When natural obstacles do not exist, mines, demolitions, barbed or concertina wire, and other concealed obstacles are employed to canalize the enemy.

Movement

The ambush force moves over a pre-selected route or routes to the ambush site. One or more mission support sites (MSSs) or rendezvous points usually are necessary along the route to the ambush site. Last-minute intelligence is provided by reconnaissance elements, and final coordination for the ambush is made at the MSS or the assembly area.

Action at the Ambush Site

The ambush force moves to an assembly area near the ambush site. Security elements take up their positions first and then the ambush elements move into place. As the approaching enemy force is detected, or at a predesignated time, the ambush force commander decides whether or not to execute the ambush. This decision is based on the size of the enemy force, enemy guard and security measures, and the estimated value of the target in light of the probable cost to the ambush force.

Executing an Ambush

If the decision is made to execute the ambush, enemy security elements or advance guards are allowed to pass through the main ambush position. When the head of the enemy main force reaches a predetermined point, then fire, demolitions, or obstacles halt it. At this signal, the entire ambush element opens fire. Designated security elements engage the enemy’s advance and rear security elements to prevent reinforcement of the main force. The volume of fire is violent, rapid, directed at enemy personnel exiting from vehicles, and concentrated on vehicles mounting automatic weapons. Antiarmor weapons (such as recoilless rifles and rocket launchers) are used against armored vehicles. Machineguns lay bands of fixed fire across escape routes, as well as in the kill zone. Mortar projectiles, hand grenades, and rifle grenades, and directional antipersonnel mines are fired into the kill zone.

If the commander decides to assault the enemy force, the assault is initiated with a prearranged signal. After the enemy has been rendered combat ineffective, designated ambush element personnel move into the kill zone to recover supplies, equipment, and ammunition.

Types of Ambush

There are three types of OPFOR ambush⎯annihilation, harassment, or containment⎯based on the desired effects and the resources available. Ambushes are frequently employed because they have a great chance of success and provide force protection. The OPFOR conducts ambushes to kill or capture personnel, destroy or capture equipment, restrict enemy freedom of movement, and collect information and supplies.

Annihilation Ambush

The purpose of an annihilation ambush is to destroy the enemy force. These are violent attacks designed to ensure the enemy’s return fire, if any, is ineffective. Generally, this type of ambush uses the terrain to the attacker’s advantage and employs mines and other obstacles to halt the enemy in the kill zone. The goal of the obstacles is to keep the enemy in the kill zone throughout the action. Using direct, or indirect, fire systems, the support element destroys or suppresses all enemy forces in the kill zone. It remains in a concealed location and may have special weapons, such as antitank weapons.

The support and ambush elements kill enemy personnel and destroy equipment within the kill zone by concentrated fires. The ambush element remains in covered and concealed positions until the enemy is rendered combat ineffective. Once that occurs, the ambush element secures the kill zone and eliminates any remaining enemy personnel that pose a threat. The Ambush element remains in the kill zone to thoroughly search for any usable information and equipment, which it takes or destroys.

The security element positions itself to ensure early warning and to prevent the enemy from escaping the kill zone. Following the initiation of the ambush, the security element seals the kill zone and does not allow any enemy forces in or out. The ambush force withdraws in sequence; the ambush element withdraws first, then the support element, and lastly the security element. The entire ambush force reassembles at a predetermined location and time. For examples of annihilation ambushes see figures 3-12 through 3-14.

Annihilation ambushes in complex terrain, including urban environments, often involve task organizations that the OPFOR calls “hunter-killer (HK) teams.” The HK team structure is extremely lethal and is especially effective for close fighting in such environments. Although other companies may be used as well, generally, infantry companies are augmented and task-organized into these HK teams. When task- organized to ambush armored vehicles, they may be called “antiarmor HK teams” or “HK infantry antiarmor teams.”

HK teams primarily fight from ground level. In urban environments, however, they prefer to attack multi-dimensionally, from basements or sewers and from upper stories and on the tops of buildings. The targets are engaged simultaneously to maximize effectiveness and confusion.

At a minimum, each HK infantry antiarmor team is composed of gunners of infantry antiarmor weapons, a machinegunner, a sniper, and one or more riflemen. Multiple HK teams simultaneously attack a single armored vehicle. Kill shots are generally made against the top, rear, and sides of vehicles from multiple dimensions. The teams prefer to trap vehicle columns in city streets where destruction of the first and last vehicles will trap the column and allow its total destruction. Single vehicles are easily defeated.

The HK teams use command detonated, controllable, and side-attack mines (antitank, anti-vehicle, and antipersonnel) in conjunction with predetermined artillery and mortar fires. Side-attack (off-route) mines may be placed out of sight, such as inside windows and alleys. Figure 3-15 on page 3-32 is an example an annihilation ambush conducted by HK teams in a complex, urban environment.

Harassment Ambush