Chapter 3: Task-Organizing

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.4 Hybrid Threat Force Structure Organization Guide.

The concept of task-organizing for combat is not unique to the Threat. It is universally, performed at all levels, and has been around as long as combat. The U.S. Army defines a task organization as “A temporary grouping of forces designed to accomplish a particular mission” and defines task-organizing as “The process of allocating available assets to subordinate commanders and establishing their command and support relationships” (ADRP 1-02). Task-organizing of the Hybrid Threat must follow Hybrid Threat doctrine (see TC 7-100, FM 7-100.1, and TC 7- 100.2) and reflect requirements for stressing U.S. units’ mission essential task list (METL) in training.

Contents

- 1 Section I - Fundamental Considerations

- 2 Section II - Threat Forces: Strategic Level

- 3 Strategic Framework

- 4 Section III - Threat Forces: Operational Level

- 5 Section IV - Threat Forces: Tactical Level

- 6 Section V - Non-State Actors

- 7 Section VI - Exploitation of Noncombatants and Civilian Assets

- 8 Section VII - Unit Symbols for OPFOR Task Organizations

- 9 Section VIII - Building an OPFOR Order of Battle

- 9.1 Step 1. Determine the Type and Size of U.S. Units

- 9.2 Step 2. Set the Conditions

- 9.3 Step 3. Select Army Tactical Tasks

- 9.4 Step 4. Select OPFOR Countertasks

- 9.5 Step 5. Determine the Type and Size of Hybrid Threat Units

- 9.6 Step 6. Review the HTFS Organizational Directories

- 9.7 Step 7. Compile the Initial Listing of Hybrid Threat Units for the Task Organization

- 9.8 Step 8. Identify the Base Unit

- 9.9 Step 9. Construct the Task Organization

- 9.10 Step 10. Repeat Steps 4 Through 9 as Necessary

Section I - Fundamental Considerations

The purpose behind task-organizing the Threat is to build an order of battle (OB) that is appropriate for U.S. training requirements. The Hybrid Threat Force structure (HTFS) organizational directories are not the Threat OB. The OB is the Threat’s go-to-war, fighting force structure.

U.S. Training Requirements

The HTFS’s reason for existence is to serve as an appropriately challenging sparring partner in U.S. training. The Threat doctrinal view, task-organizing is a top-down process, the process of building the Threat Force Structure for a training event is best approached in a bottom-up manner—for practical purposes. That is because the task organizations at one level of command are the building blocks for determining the overall organization and total equipment holdings of the next-higher command. From the perspective of U.S. Army training, OPFOR task organization is also based on the missions and tasks the Hybrid Threat needs to perform in order to stress U.S. units’ METL.

At some point, the holdings of the higher levels of command become irrelevant to a particular training event. Generally, this occurs when those assets no longer have an effect on Hybrid Threat capabilities within the particular area of responsibility (AOR) where the training event occurs. If trainers build the Threat Force Structure from the bottom up, they will know when to stop—or at least when all they need is a general organizational outline, rather than a detailed OB.

Note. It is possible to have a training scenario that begins when the Hybrid Threat is still entirely in its peacetime HTFS—or that peacetime organization is all the U.S. force knows about the Threat’s organization. Then an implied task for the U.S. unit(s) would be to conduct further OB analysis to determine what parts of the threat currently have been task-organized and how. In most cases, however, the training scenario begins at a point when the Hybrid Threat has already task-organized its forces for combat. In those cases, the HTFS as a whole is merely a part of the road to war, which outlines how this fight came to take place and how the U.S. unit(s) become challenged by certain threat unit(s). Aside from specific organizations designed to perform specific countertasks to challenge U.S. METL tasks, everything else could be a mere backdrop— to explain the larger context in which this particular fight occurs and perhaps where some of the assets came from to form this particular Threat Force Structure.

Hybrid Threat Doctrine

U.S. training requirements normally dictate the size and type of Hybrid Threat needed. Nevertheless, the Threat Force Structure needs to make sense within the Hybrid Threat doctrinal framework, including the task-organizing process. From the Hybrid Threat doctrinal view, task-organizing is a top-down process. That is because the higher commander is always the one who decides the missions of his subordinates and allocates additional resources for some of those missions. The allocated units can have several types of command and support relationship with the receiving command.

Allocation and Suballocation of Assets

OPFOR commanders must consider where the assets required for a particular task organization are located within the threat force structure (TFS) and how to get them allocated to the task organization that needs them. Particularly at the tactical level, the base organization around which a tactical group or detachment is formed may not have the organizational or equipment assets necessary to carry out the mission. Its next higher headquarters might have such assets at its disposal to allocate downward, or those assets might first have to be allocated from outside that parent organization in order for the parent organization to further suballocate them to the task organization. The latter could be the case, for instance, when a brigade tactical group (BTG) within a division or division tactical group (DTG) needs attack helicopters to augment its fire support or transport helicopters to enable a heliborne landing. If the BTG needs these assets in a subordinate (constituent or dedicated) command relationship rather than just a supporting relationship, a higher headquarters would have to allocate the helicopter units to the division or DTG, which would in turn suballocate them to this BTG.

When tactical-level commands become part of the fighting force structure, they often receive additional assets that better enable them to perform a mission for which they are task-organized. If some of their original subordinates are inappropriate or otherwise not required for the assigned mission, the tactical- level organizations typically leave these behind, under the command and control (C2) of their next-higher headquarters that remains in the TFS framework. The higher headquarters could provide these units to another task organization or hold them in reserve for possible future requirements.

Note. The Hybrid Threat must understand its own strengths and weaknesses, and those of its enemy. An OPFOR commander must consider how to counter or mitigate what the other side has and/or how to exploit what he has on his own side. The mitigation or exploitation may be by means of equipment, tactics, or organization—or more likely all of these. However, the process generally starts with the proper task organization of forces with the proper equipment to facilitate appropriate tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP).

Hybrid Threat Command and Support Relationships

Hybrid Threat units are organized using four command and support relationships, summarized in table 3-1 and described in the following paragraphs. Command relationships define command responsibility and authority; they establish the degree of control and responsibility commanders have on forces operating under their control. Support relationships define the purpose, scope, and effect desired when one capability supports another. These relationships may shift during the course of an operation in order to best align the force with the tasks required. The general category of subordinate units includes both constituent and dedicated relationships; it can also include interagency and multinational (allied) subordinates.

| Relationship | Commanded by | Logistics from | Positioned by | Priorities from |

| Constituent | Gaining | Gaining | Gaining | Gaining |

| Dedicated | Gaining | Parent | Gaining | Gaining |

| Supporting | Parent | Parent | Supported | Supported |

| Affiliated | Self | Self or “Parent” | Self | Mutual Agreement |

Constituent

Constituent units are those forces assigned directly to a unit and forming an integral part of it. They may be organic to the table of organization and equipment of the administrative structure forming the basis of a given unit, assigned at the time the unit was created, or attached to it after its formation. From the view of an OPFOR commander, a unit has the same relationship to him regardless of whether it was originally organic or was later assigned or attached.

Dedicated

Dedicated is a command relationship identical to constituent with the exception that a dedicated unit still receives logistics support from a parent organization of similar type. An example of a dedicated unit would be the case where one or two surface-to-surface missile (SSM) battalions from an SSM brigade could be dedicated to an operational-strategic command (OSC). Since the OSC does not otherwise possess the technical experts or transloading equipment for missiles, the dedicated relationship permits the SSM battalion(s) to fire exclusively for the OSC while still receiving its logistics support from the parent SSM brigade. Another example of a dedicated unit would be the case where a specialized unit, such as an attack helicopter company, is allocated to a brigade tactical group (BTG). Since the base brigade does not otherwise possess the technical experts or repair facilities for the aviation unit’s equipment, the dedicated relationship permits the helicopter company to execute missions exclusively for the BTG while still receiving its logistics support from its parent organization. In Hybrid Threat plans and orders, the dedicated command relationship is indicated by “(DED)” next to a unit title or symbol.

Note. The dedicated relationship is similar to the U.S. concept of operational control (OPCON), but also describes a specific logistics arrangement. This is something for exercise designers to consider when developing the Threat Force Structure. They should not “chop” part of an SSM unit to an OSC, DTG or BTG without its support structure. If the gaining unit does not have the ability to support the SSM unit logistically, it might be better to keep it in a dedicated relationship. If the gaining unit also does not have the capability to exercise command over the SSM unit, it might be better to keep it in a supporting relationship.

Supporting

Supporting units continue to be commanded by and receive their logistics from their parent headquarters, but are positioned and given mission priorities by their supported headquarters. This relationship permits supported units the freedom to establish priorities and position supporting units while allowing higher headquarters to rapidly shift support in dynamic situations. The supporting unit does not necessarily have to be within the supported unit’s AOR. An example of a supporting unit would be a fighter-bomber regiment supporting an OSC for a particular phase of the strategic campaign plan (SCP) but ready to rapidly transition to a different support relationship when this OSC becomes the theater reserve in a later phase. Another example of a supporting unit would be a multiple rocket launcher (MRL) battalion supporting a BTG for a particular phase of an operation but ready to rapidly transition to a different support relationship when the BTG becomes the DTG reserve in a later phase. In Hybrid Threat plans and orders, the supporting relationship is indicated by “(SPT)” next to a unit title or symbol.

Note. The supporting relationship is the rough equivalent of the U.S. concept of direct support (DS). Note that there is no general support (GS) equivalent. That is because what would be GS in the U.S. Army is merely something that is constituent to the parent command in the OPFOR. In U.S. doctrine the format for task-organizing says: “List subordinate units under the C2 headquarters to which they are assigned, attached, or in support. Place DS units below the units they support.” In the threat force structure, therefore, units in the supporting status (like U.S. DS) could be considered part of the task organization of the “supported” unit. For units that are supporting, but not subordinate, it may be better to keep them and their equipment listed under their parent unit’s assets, unless that parent unit is not included in the OB. In any case, trainers will need to know what part of the parent unit will actually affect the situation.

Affiliated

Affiliated organizations are those operating in a unit’s AOR that the unit may be able to sufficiently influence to act in concert with it for a limited time. No “command relationship” exists between an affiliated organization and the unit in whose AOR it operates. Affiliated organizations are typically nonmilitary or paramilitary groups such as criminal organizations, terrorists, or insurgents. In some cases, affiliated forces may receive support from the OSC, DTG, or BTG as part of the agreement under which they cooperate. Although there would typically be no formal indication of this relationship in Hybrid Threat plans and orders, in rare cases “(AFL)” is used next to unit titles or symbols.

Note. Although there is no “command” relationship between the two organizations, the military command may have the ability to influence an affiliated paramilitary organization to act in concert with it for a limited time. For example, it might say: “If you are going to set off a car bomb in the town square, we would appreciate it if you could do it at 3 o’clock tomorrow afternoon.” In organizational charts for threat force structure, affiliated forces are shown with a dashed line (rather than a solid one) connecting them to the rest of the task organization. The dashed line indicates only a loose affiliation, but no direct command relationship with the military unit with which they are affiliated. For units that are affiliated, but not subordinate, it may be better to list their personnel and equipment separately or under their parent unit’s assets, if there is a parent organization. However, trainers will need to know what part of the parent unit will actually affect the situation. If affiliated forces are not included in organization charts or equipment totals for the task organization, they have to be accounted for elsewhere in the OB.

Section II - Threat Forces: Strategic Level

In the wartime fighting force structure, the national-level command structure still includes the National Command Authority (NCA), the Ministry of Defense (MOD), and the General Staff. The only difference is that the MOD and General Staff merge to form the Supreme High Command. How the Armed Forces are organized and task-organized depends on the type of operations they are conducting under the State’s strategic framework.

Supreme High Command

In wartime, the State’s NCA exercises C2 via the Supreme High Command (SHC), which includes the MOD and a General Staff drawn from all the service components. In peacetime, the MOD and General Staff operate closely but separately. During wartime, the MOD and General Staff merge to form the SHC, which functions as a unified headquarters. (See figure 3-1.)

Strategic Framework

For most training scenarios, strategic-level organizations serve only as part of the road to war background. Within the Hybrid Threat strategic framework, it makes a difference whether the exercise portion of the scenario takes place during regional, transition or adaptive operations. (See TC 7-100 for more detail on these strategic-level courses of action.)

For regional operations against a weaker neighboring country, the Hybrid Threat might not have needed to use all the forces in its HTFS in forming its fighting force structure—only “all means necessary” for the missions at hand. As U.S. and/or coalition forces begin to intervene, the Hybrid Threat begins transition operations and shifts more HTFS units into the wartime fighting structure—possible mobilizing reserves and militia to supplement regular forces. For adaptive operations against U.S. and coalition forces, the Hybrid Threat would use “all means available.” Even those forces that were previously part of the fighting force structure might need to be task-organized differently in order to deal with extraregional intervention.

If the Hybrid Threat is originally task-organized to fight a regional neighbor, it would (if it has time) modify that task organization in preparation for fighting an intervening U.S. or coalition force. Threat units may have suffered combat losses during the original fight against a neighboring country or in the early stages of the fight against U.S. or coalition forces. In such cases, the threat force structure might have to change in order to sustain operations. Lost or combat-ineffective units might be replaced by units from the reserves, paramilitary units from the Internal Security Forces, or regular military units from other commands, which are still combat effective—or by additional units from the HTFS. If not already the case, Hybrid Threat military forces may incorporate irregular forces (insurgent, guerrilla, or even criminal), at least in an affiliated relationship.

Section III - Threat Forces: Operational Level

In the peacetime HTFS, each service of the Armed Forces commonly maintains its forces grouped under single-service operational-level commands (such as corps, armies, or army groups) for administrative purposes. In some cases, forces may be grouped administratively under operational-level geographical commands designated as military regions or military districts. (See chapter 2 for more detail on these administrative groupings.) However, these administrative groupings normally differ from the Armed Forces’ go-to-war (fighting) force structure. (See figure 3-1.)

In wartime, most major administrative commands continue to exist under their respective service headquarters. However, their normal role is to serve as force providers during the creation of operational- level fighting commands, such as field groups (FGs) or operational-strategic commands (OSCs). OSC headquarters may exist in peacetime, for planning purposes, but would not yet have any forces actually subordinate to them. The same would be true of any theater headquarters planned to manage multiple OSCs. FGs, on the other hand, are not normally standing headquarters, but may be organized during full mobilization for war.

The original operational-level administrative headquarters normally remain “in garrison” during conflict. After transferring control of its major fighting forces to one or more task-organized fighting commands, an administrative headquarters, facility, or installation continues to provide depot- and area support-level administrative, supply, and maintenance functions. A geographically-based administrative command also provides a framework for the continuing mobilization of reserves to complement or supplement regular forces.

In rare cases, an administrative command could function as a fighting command. This could occur, for instance, when a particular administrative command happens to have just the right combination of forces for executing a particular strategic campaign plan. (This is not likely to be the case at division level and higher.) Another case would be in times of total mobilization, when an administrative command has already given up part of its forces to a fighting command and then is called upon to form a fighting command with whatever forces remain under the original administrative headquarters.

The operational level of command is that which executes military tasks assigned directly by a strategic campaign plan (SCP). The most common Hybrid Threat operational-level commands are FGs and OSCs. There is also the possibility that a division or DTG could be directly subordinate to the SHC in the fighting force structure and thus perform tasks assigned directly by an SCP. In such cases, the Hybrid Threat would consider the divisions or DTGs to be operational-level commands. More typically, however, they perform tactical missions as subordinates of an FG or OSC.

Field Group

A field group is the largest operational-level organization, since it has one or smaller operational- level commands subordinate to it. An FG is a grouping of subordinate organizations with a common headquarters, a common AOR, and a common operation plan. FGs are always joint and interagency organizations and are often multinational. However, this level of command may or may not be necessary in a particular SCP. An FG may be organized when the number of forces and/or the number of major military efforts in a theater exceeds the theater commander’s desired or achievable span of control. This can facilitate the theater commander’s remaining focused on the theater-strategic level of war and enable him to coordinate effectively the joint forces allocated for his use.

The General Staff does not normally form standing FG headquarters, but may organize one or more during full mobilization, if necessary. An FG can be assigned responsibilities in controlling forces in the field during adaptive operations in the homeland, or forward-focused functionally (an FG may be assigned an access-control mission). However, FGs may exist merely to accommodate the number of forces in the theater.

FGs are typically formed for one or more of the following reasons:

- An SCP may require a large number of OSCs and/or operational-level commands from the HTFS. When the number of major military efforts in a theater exceeds the theater commander’s desired or achievable span of control, he may form one or more FGs.

- In rare cases when multiple operational-level commands from the HTFS become fighting commands, they could come under the control of an FG headquarters.

- Due to modifications to the SCP, a standing operational-level headquarters that was originally designated as an OSC headquarters may receive one or more additional operational-level commands from the HTFS as fighting commands. Then the OSC headquarters would transition into an FG headquarters.

Operational Strategic Command

The Hybrid Threat’s primary operational organization is the OSC. Once the General Staff writes a particular SCP, it forms one or more standing OSC headquarters. Each OSC headquarters is capable of controlling whatever combined arms, joint, interagency, or multinational operations are necessary to execute that OSC’s part of the SCP. However, the OSC headquarters does not have any forces permanently assigned to it.

Figure 3-2 shows an example of allocation of forces to an OSC. A basic difference between an OSC and tactical-level task organizations is that the latter are built around an existing organization. In the case of an OSC, however, all that exists before task-organizing is the OSC headquarters. Everything else is this example is color coded to show where it came from. Figure 3-2 shows under the OSC all the major units from the TFS that are allocated to the OSC headquarters in this example, but does not reflect how those units might be task organized within the OSC.

The units allocated from the TFS to form the OSC typically come from an army group, army, or corps (or perhaps a military district or military region) or from forces directly subordinate to a service headquarters. There can also be cases where forces from the services have initially been allocated to a theater headquarters and are subsequently re-allocated down to the OSC. The organizations shown under the OSC, like those shown under the theater headquarters in this example, indicate a pool of assets made available to that command. The commander receiving these assets may choose to retain them at his own level of command, or he may choose to sub-allocate them down to one or more of his subordinates for their use in their own task organization.

When the NCA decides to execute a particular SCP, each OSC participating in that plan receives appropriate units from the TFS, as well as interagency and/or multinational forces. Forces subordinated to an OSC may continue to depend on the TFS for support.

If a particular OSC has contingency plans for participating in more than one SCP, it could receive a different set of forces under each plan. In each case, the forces would be task-organized according to the mission requirements in the given plan. Thus, each OSC consists of those division-, brigade-, and battalion- size organizations allocated to it by the SCP currently in effect. These forces also may be allocated to the OSC for the purpose of training for a particular SCP. When an OSC is neither executing tasks as part of an SCP nor conducting exercises with its identified subordinate forces, it exists as a planning headquarters.

Figure 3-3 shows an example of the types of organizations that could make up a particular OSC organization. The numbers of each type of subordinate and whether they actually occur in a particular OSC can vary. As shown in this example, the composition of an OSC is typically joint, with Air Force and possibly maritime (naval or naval infantry) units, and it can also be interagency. If some of the allocated forces come from another, allied country, the OSC could be multinational. The simplified example of an OSC shown here does not show all the combat support and combat service support units that would be present in such an organization. Many of these support units are found in the integrated fires command and the integrated support command (outlined below). Other support units could be allocated initially from the TFS to the OSC, which further allocates them to its tactical subordinates.

Once allocated to an OSC, a division or brigade often receives augmentation that transforms it into a DTG or BTG, respectively. However, an OSC does not have to task-organize subordinate divisions and brigades into tactical groups. Most divisions would become DTGs, but some maneuver brigades in the TFS may be sufficiently robust to accomplish their mission without additional task-organizing.

The Hybrid Threat has great flexibility regarding possible OSC organizations for different missions. There is virtually no limit to the possible permutations that could exist. The allocation of organizations to an OSC depends on what is available in the State’s TFS, the mission requirements of that OSC, and the requirements of other operational-level commands. In a U.S. Army training exercise, the OSC should get whatever it needs to give the U.S. unit a good fight and challenge its METL tasks.

Integrated Fires Command

The integrated fires command (IFC) is a combination of a standing C2 structure and task organization of constituent and dedicated fire support units. (See figure 3-4.) All division-level and above Hybrid Threat organizations possess an IFC C2 structure. The IFC exercises command of all constituent and dedicated fire support assets retained by its level of command. This includes aviation, artillery, and missile units. It also exercises command over all reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) assets allocated to it. Any units that an OSC (or any headquarters at echelons above division) suballocates down to its subordinates are no longer part of its IFC. (See FM 7-100.1 for more detail on the IFC at OSC level.)

Note. Based on mission requirements, the commander may also allocate maneuver forces to the IFC. This is most often done when he chooses to use the IFC command post to provide C2 for a strike, but can also be done for the execution of other missions.

The number and type of fire support and RISTA units allocated to an IFC is mission-dependent. The IFC is not organized according to a table of organization and equipment, but is task-organized to accomplish the missions assigned.

IFC Headquarters

The OSC IFC headquarters, like the overall OSC headquarters, exists in peacetime in order to be ready to accommodate and exercise C2 over all forces made subordinate to it in wartime. The IFC headquarters is composed of the IFC commander and his command group, a RISTA and information warfare (INFOWAR) section, an operations section, and a resources section. Located within the operations section is the fire support coordination center (FSCC). To ensure the necessary coordination of fire support and associated RISTA, the operations section of the IFC headquarters also includes liaison teams from subordinate units.

Artillery Component

The artillery component is a task organization tailored for the conduct of artillery support during combat operations. In an OSC’s IFC, it is typically organized around one or more artillery brigades, or parts of these that are not allocated in a constituent or dedicated relationship to tactical-level subordinates. The artillery component includes appropriate target acquisition, C2, and logistics support assets.

The number of artillery battalions assigned to an IFC varies according such factors as mission of friendly units, the enemy (U.S.) situation, and terrain. However, the number of artillery units also can vary based on the capabilities of the supporting artillery fire control system.

Aviation Component

The aviation component is a task organization tailored for the conduct of aviation operations. The aviation component is task-organized to provide a flexible and balanced air combat organization capable of providing air support to the OSC commander. It may be organized around an Air Force aviation regiment or an air army, or parts of these, as required by the mission. It may also include rotary-wing assets from Army aviation. It includes ground attack aviation capability as well as requisite ground and air service support assets.

Missile Component

The missile component is a task organization consisting of long-range missiles or rockets capable of delivering conventional or chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) munitions. It is organized around an SSM or rocket battalion or brigade and includes the appropriate logistics support assets. Missile and rocket units may come from the Strategic Forces or from other parts of the TFS (where they may be part of a corps, army, or army group).

Special-Purpose Forces Component

The SPF component normally consists of assets from an SPF brigade. Units may come from the national-level SPF Command or from Army, Air Force, and Navy SPF. If an OSC has received SPF units, it may further allocate some of these units to supplement the long-range reconnaissance assets a division or DTG has in its own IFC. However, the scarce SPF assets normally would remain at OSC level.

RISTA Component

The RISTA component normally consists of assets from the RISTA Command. All reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) assets allocated to the RISTA command are used to create of windows of opportunity that permit OPFOR units to move out of sanctuary and attack. Threat RISTA can do this by locating and tracking key elements of the enemy’s C2, RISTA, air defense, and long- range fires systems for attack.

Reconnaissance Intelligence Surveillance Target Acquisition Command

The reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition command (RISTA) is a combination of a standing C2 structure and task organization of constituent and dedicated reconnaissance units. (See figure 3-5.) All Army level Hybrid Threat organizations possess a RISTA C2 structure. The RISTA command exercises command over all reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) assets allocated to it. Any units that an OSC (or any headquarters at echelons above division) suballocates down to its subordinates are no longer part of its RISTA.

The IFC exercises command over all reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) assets allocated to it. The number and type of fire support and RISTA units allocated to an IFC is mission-dependent.

Targets of Hybrid Threat RISTA assets during regional operations include the enemy’s

- Precision weapons delivery means.

- Long-range fire systems.

- WMD.

- RISTA assets.

Integrated Support Group

The integrated support group (ISG) is a compilation of units performing logistics tasks that support the IFC in a constituent or dedicated command relationship. For organizational efficiency, various units performing other combat support and combat service support tasks might be grouped into the ISG, even though they may support only one of the major units or components of the IFC. The ISG can perform the same functions as the OSC’s integrated support command (see below), but on a different scale and tailored to the support requirements of the IFC

There is no standard ISG organizational structure. The number, type, and mix of subordinate units vary based on the operational support situation. In essence, the ISG is tailored to the mission and the task organization of the IFC. An ISG can have many of the same types of units as shown in figure 3-6 for one example of ISC subordinates, but tailored in size and functions to support the IFC.

Integrated Support Command

The integrated support command (ISC) is the aggregate of combat service support units (and perhaps some combat support units) allocated from the TFS to an OSC or a division in a constituent or dedicated command relationship and not suballocated in a constituent or dedicated command relationship to a subordinate headquarters within the OSC. Normally, the OSC further allocates part of its combat service support units to its tactical-level subordinates and some, as an ISG, to support its IFC. The rest remain in the ISC at OSC level to provide overall support of the OSC. For organizational efficiency, other combat service support units may be grouped in this ISC, although they may support only one of the major units of the OSC. Sometimes, an ISC might also include units performing combat support tasks (such as chemical defense, INFOWAR, or law enforcement) that support the OSC. Any units that an OSC suballocates down to its subordinates are no longer part of its ISC. (See FM 7-100.1 for more detail on the ISC at OSC level.)

ISC Headquarters

The ISC headquarters is composed of the ISC commander and his command group, an operations section, and a resources section. The operations section provides the control, coordination, communications, and INFOWAR support for the ISC headquarters. Located within the operations section is the support operations coordination center (SOCC). The SOCC is the staff element responsible for the planning and coordination of support for the OSC. In addition to the SOCC, the operations section has subsections for future operations and airspace operations. The resources section consists of logistics and administrative subsections which, respectively, execute staff supervision over the ISC’s logistics and personnel support procedures. The ISC headquarters includes liaison teams from subordinate units of the ISC and from other OSC subordinates to which the ISC provides support. These liaison teams work together with the SOCC to ensure the necessary coordination of support for combat operations.

ISC Task-Organizing

The units allocated to an OSC and its ISC vary according to the mission of that OSC and the support requirements of other operational-level commands. The OSC resources officer (in consultation with his chiefs of logistics and administration and the ISC commander) determines the proper task organization of logistics and administrative support assets allocated to the OSC. He suballocates some assets to the IFC and to other OSC subordinates based on support mission requirements. The remainder he places under the ISC commander. Figure 3-6 above shows a typical OSC organization, with an example of the types of combat service support and combat support units that might appear in an OSC ISC.

The number and type of units in the ISC and ISG will vary according to the number and size of supported units in the OSC and its IFC, respectively. For example, an ISC supporting an OSC composed mainly of tank and mechanized infantry units will differ from an ISC supporting an OSC composed mainly of infantry or motorized infantry units. When the logistics units are no longer required for ISC or ISG functions, they will revert to control of their original parent units in the TFS or otherwise will be assigned to other operational-level commands, as appropriate.

Section IV - Threat Forces: Tactical Level

In the TFS, the largest tactical-level organizations are divisions and brigades. In wartime, they are often subordinate to a larger, operational-level command. Even in wartime, however, some separate single- service tactical commands (divisions, brigades, or battalions) may remain under their respective service headquarters or come under the direct control of the SHC or a separate theater headquarters. (See figure 3-1.) In any of these wartime roles, a division or brigade may receive additional assets that transform it into a tactical group.

Tactical Groups

A tactical group is a task-organized division or brigade that has received an allocation of additional land forces in order to accomplish its mission. Thus, a tactical group differs from higher-level task organizations in that it is built around the structure of an already existing organization. Tactical groups formed from divisions are division tactical groups (DTGs), and those formed from brigades are brigade tactical groups (BTGs). In either of those cases, the original division or brigade headquarters becomes the DTG or BTG headquarters, respectively.

The additional forces that transform a division or brigade into a tactical group may come from within the MOD, from the Ministry of the Interior, or from affiliated forces. Typically, these assets initially are allocated to an OSC or FG, which further allocates them to its tactical subordinates. If the tactical group operates as a separate command, it may receive additional assets directly from the theater headquarters or the SHC that are necessary for it to carry out an operational-level mission. If a DTG has a mission directly assigned by an SCP or theater campaign plan, it acts as an operational-level command. If a DTG has a mission assigned by an intermediate operational-level command (such as an FG or an OSC), then it acts as a tactical-level command.

A DTG or BTG may receive augmentation from other services of the State’s Armed Forces. However, it does not become joint. That is because it can accept such augmentation only in the form of land forces, such as special-purpose forces from the SPF Command or naval infantry from the Navy. Augmentation may also come from other agencies of the State government, such as border guards or national police that have not been resubordinated to the SHC in wartime.

Any division or brigade receiving additional assets from a higher command becomes a DTG or BTG. In addition to augmentation received from a higher command, a DTG or BTG normally retains the assets that were originally subordinate to the division or brigade that served as the basis for the tactical group. However, it is also possible that the same higher command that augments a division or brigade to transform it into a tactical group could use units from one division or brigade as part of a tactical group that is based on another division or brigade. The purpose of a tactical group is to ensure unity of command for all land forces in a given AOR.

A DTG may fight as part of an OSC or as a separate unit in an FG or directly under a theater headquarters or the SHC. A BTG may fight as part of a division or DTG or as a separate unit in an OSC or FG.

Divisions and DTGs

Divisions in the TFS are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a division tactical group (DTG), if necessary. Thus, they are able to—

- Accept constituent flame weapons, artillery (cannon and rocket), engineer, air defense, chemical defense, antitank, medical, logistics, signal, and INFOWAR units.

- Accept dedicated and supporting surface-to-surface missile (SSM), Special-Purpose Forces (SPF), aviation (combat helicopter, transport helicopter), and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) units. A division may accept these type units as constituent if it is also allocated their essential logistics support.

- Integrate interagency forces up to brigade size.

Figure 3-7 gives an example of possible DTG organization. Some of the units belonging to the DTG are part of the division on which it is based. Note that some brigades are task-organized into BTGs, while others may not be and have structures that come straight out of the organizational directories for the TFS. Likewise, some battalions and companies may become detachments. Besides what came from the original division structure, the rest of the organizations shown come from a pool of assets the parent operational- level command has received from the TFS and has decided to pass down to the DTG. All fire support units that were organic to the division or allocated to the DTG (and are not suballocated down to a BTG) go into the integrated fires command (IFC). Likewise, combat service support units go into the integrated support command (ISC). As shown here, DTGs can also have affiliated forces from paramilitary organizations.

The division that serves as the basis for a DTG may have some of its brigades task-organized as BTGs. However, just the fact that a division becomes a DTG does not necessarily mean that it forms BTGs. A DTG could augment all of its brigades, or one or two brigades, or none of them as BTGs. A division could augment one or more brigades into BTGs, using the division’s own constituent assets, without becoming a DTG. If a division receives additional assets and uses them all to create one or more BTGs, it is still designated as a DTG.

Maneuver Brigades and BTGs

In the TFS, divisional or separate maneuver brigades are robust enough to accomplish some missions without further allocation of forces. However, maneuver brigades are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a brigade tactical group (BTG), if necessary. Thus, they are able to—

- Accept constituent flame weapons, artillery (cannon and rocket), engineer, air defense, antitank, logistics, and signal units.

- Accept dedicated and supporting chemical defense, medical, EW, SSM, SPF, aviation (combat helicopter, transport helicopter), and UAV units. A brigade may accept these type units as constituent if it is also allocated their essential logistics support.

- Integrate interagency forces up to battalion size.

Figure 3-8 give an example of possible BTG organization. This example shows that some battalions and companies of a BTG may be task-organized as detachments, while others are not. Although not shown here, BTGs (and higher commands) can also have affiliated forces from paramilitary organizations.

Unlike higher-level commands, Hybrid Threat brigades and BTGs do not have an IFC or an ISC. Brigade and BTG headquarters have a fire support coordination center (FSCC) in their operations section, but are not expected to integrate fires from all systems and services without augmentation.

Detachments

A detachment is a battalion or company designated to perform a specific mission and allocated the forces necessary to do so. Detachments are the Hybrid Threat’s smallest combined arms formations and are, by definition, task-organized. To further differentiate, detachments built from battalions can be termed BDETs and those from companies CDETs. The forces allocated to a detachment suit the mission expected of it. They may include—

- Artillery or mortar units.

- Air defense units.

- Engineer units (with obstacle, survivability, or mobility assets).

- Heavy weapons units (including heavy machineguns, automatic grenade launchers, and antitank guided missiles).

- Units with specialty equipment such as flame weapons, specialized reconnaissance assets, or helicopters.

- Chemical defense, antitank, medical, logistics, signal, and INFOWAR units.

- Interagency forces up to company for BDETs or platoon for CDETs.

BDETs can accept dedicated and supporting SPF, aviation (combat helicopter, transport helicopter) and UAV units. Figures 3-9 and 3-10 provide examples of a BDET and a CDET, respectively.

The basic type of OPFOR detachment—whether formed from a battalion or a company—is the independent mission detachment. Independent mission detachments are formed to execute missions that are separated in space and/or time from those being conducted by the remainder of the forming unit. Other common types of detachment include—

- Counterreconnaissance detachment.

- Movement support detachment.

- Obstacle detachment.

- Reconnaissance detachment.

- Security detachment.

- Urban detachment.

Integrated Fires Command

A division or DTG would have an IFC similar to that found in an operational-level command (see figure 3-7). The primary difference is that its aviation component would include only Army aviation assets. Also, rather than an “SPF component” as at the operational level, the division or DTG IFC would have a “long-range reconnaissance component” that most often would not include scarce SPF assets. Even when allocated to a DTG, probably in a supporting status, the SPF would pursue tactical goals in support of operational objectives. Any units that a division or DTG suballocates down to its subordinates are no longer part of its IFC. An IFC C2 structure Figure 3-11 and task organization is not found below division or DTG level. (See TC 7-100.2 for more detail on the IFC at division or DTG level.)

Note. In rare cases, such as when a division or DTG would have the mission of conducting a strike, the commander might also allocate maneuver forces to the IFC.

Integrated Support Command

A division or DTG would have an ISC similar to that found in an OSC (see figure 3-7). An ISC C2 structure and task organization is not found below division or DTG level. Any units that a division or DTG suballocates down to its subordinates are no longer part of its ISC. (See TC 7-100.2 for more detail on the ISC at division or DTG level.)

Internal Task-Organizing

Given the pool of organizational assets available to him, a commander at any level has several options regarding the task-organizing of his subordinates. An OSC is always a task organization. An OSC allocated divisions and/or separate brigades would almost always provide those immediate tactical-level subordinates additional assets that would transform them into DTGs and BTGs tailored for specific missions. However, it is not necessary that all divisions or divisional brigades (or even separate brigades) become tactical groups. That is the higher commander’s option.

At any level of command, a headquarters can direct one or more of its subordinates to give up some of their assets to another subordinate headquarters for the creation of a task organization. Thus, a division could augment one or more brigades into BTGs, using the division’s own constituent assets, without becoming a DTG. A brigade, using its own constituent assets, could augment one or more battalions into BDETs (or direct a battalion to form one or more CDETs) without becoming a BTG. A battalion could use its own constituent assets to create one or more CDETs without becoming a BDET.

If a division receives additional assets and uses them all to create one or more BTGs, it is still designated as a DTG. If a brigade receiving additional assets does not retain any of them at its own level of command but uses them all to transform one or more of its battalions into BDETs, it is still a BTG.

Special-Purpose Forces

In wartime, some SPF units from the SPF Command or from the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Internal Security Forces SPF may remain under the command and control of their respective service headquarters. However, some SPF units also might be suballocated to operational- or even tactical-level commands during the task-organizing process.

When the Hybrid Threat establishes more than one theater headquarters, the General Staff may allocate some SPF units to each theater. From those SPF assets allocated to him in a constituent or dedicated relationship, the theater commander can suballocate some or all of them to a subordinate OSC.

The General Staff (or a theater commander with constituent or dedicated SPF) can allocate SPF units to an OSC in a constituent or dedicated relationship or place them in support of an OSC. These command and support relationships ensure that SPF objectives support the overall mission of the OSC to which the SPF units are allocated. Even in a supporting relationship, the commander of the OSC receiving the SPF unit(s) establishes those units’ objectives, priorities, and time of deployment. The OSC commander may employ the SPF assets allocated to him as constituent or dedicated as part of his integrated fires command (IFC), or he may suballocate some or all of them to his tactical-level subordinates. Even SPF units allocated to an OSC may conduct strategic missions, if required.

The SPF units of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Internal Security Forces may remain under the control of their respective services (or be allocated to a joint theater command). However, they are more likely to appear in the task organization of an OSC. In that case, the OSC commander may choose to suballocate them to tactical-level subordinates. If necessary, SPF from any of these service components could become part of joint SPF operations in support of national-level requirements. In that case, they could temporarily come under the control of the SPF Command or the General Staff.

Regardless of the parent organization in the HTFS, SPF normally infiltrate and operate as small teams. When deployed, these teams may operate individually, or they may be task-organized into detachments. The terms team and detachment indicate the temporary nature of the groupings. In the course of an operation, teams can leave a detachment and join it again. Each team may in turn break up into smaller teams (of as few as two men) or, conversely, come together with other teams to form a larger team, depending on the mission. At a designated time, teams can join up and form a detachment (for example, to conduct a raid), which can at any moment split up again. This whole process can be planned before the operation begins, or it can evolve during the course of an operation.

Internal Security Forces

During wartime, some or all of the internal security forces from the Ministry of the Interior become subordinate to the SHC. Thus, they become the sixth service component of the Armed Forces, with the formal name “Internal Security Forces.” The SHC might allocate units of the Internal Security Forces to a theater command or to a task-organized operational- or tactical-level military command that is capable of controlling joint and/or interagency operations. In such command relationships, or when they share a common area of responsibility (AOR) with a military organization, units of the Internal Security Forces send liaison teams to represent them in the military organization’s staff. (See chapter 2 of this manual and TC 7-100.3 for more detail on the various types of internal security forces and their possible roles in the OPFOR’s wartime fighting force structure.)

Section V - Non-State Actors

Various types on non-state actors might be part of the Hybrid Threat, affiliated with it, or support it in some manner. Even those who do not belong to the Hybrid Threat or support it directly or willingly could be exploited or manipulated by the Hybrid Threat to support its objectives.

Insurgent and Guerrilla Forces

Insurgent organizations are irregular forces, meaning that there is no “regular” table of organization and equipment. Thus, the baseline insurgent organizations in the organizational directories represent the “default” setting for a “typical” insurgent organization. If a Hybrid Threat has more than one local insurgent organization, no two insurgent organizations should look exactly alike. Trainers and training planners should vary the types and numbers of cells to reflect the irregular nature of such organizations.

The baseline organization charts and equipment lists for individual cells include many notes on possible variations in organization or in numbers of people or equipment within a given organization. When developing an OB for a specific insurgent organization for use in training, users may exercise some latitude in the construction of cells. Some cells might need to be larger or smaller than the “default” setting found in the organizational directories. Some entire cells might not be required, and some functional cells might be combined into a single cell performing both functions. However, trainers and training planners would need to take several things into consideration in modifying the “default” cell structures:

- What functions the insurgents need to be able to perform.

- What equipment is needed to perform those functions.

- How many people are required to employ the required equipment.

- The number of vehicles in relation to the people needed to drive them or the people and equipment that must be transported.

- Equipment associated with other equipment (for example, an aiming circle/goniometer used with a mortar or a day/night observation scope used with a sniper rifle).

Any relationship of independent local insurgent organizations to regional or national insurgent structures may be one of affiliation or dependent upon a single shared or similar goal. These relationships are generally fluctuating and may be fleeting, mission dependent, or event- or agenda-oriented. Such relationships can arise and cease due to a variety of reasons or motivations.

When task-organizing insurgent organizations, guerrilla units might be subordinate to a larger insurgent organization, or they might be loosely affiliated with an insurgent organization of which they are not a part. A guerrilla unit or other insurgent organization might be affiliated with a regular military organization. A guerrilla unit might also become a subordinate part of an OPFOR task organization based on a regular military unit.

Even in the HTFS organizational directories, some guerrilla units were already reconfigured as hunter/killer units. In the fighting force structure represented in a Threat Force Structure, some additional guerrilla units may become task-organized in that manner.

Other Paramilitary Forces

Insurgent and guerrilla forces are not the only paramilitary forces that can perform countertasks that challenge a U.S. unit’s METL. Other possibilities are criminal organizations and private security organizations. Sometimes the various types of paramilitary organizations operate in conjunction with each other when it is to their common benefit.

Criminal Organizations

Criminal organizations may employ criminal actions, terror tactics, and militarily unconventional methods to achieve their goals. They may have the best technology, equipment, and weapons available, simply because they have the money to buy them. Criminal organizations may not change their structure in wartime, unless wartime conditions favor or dictate different types of criminal action or support activities.

The primary motivation of drug and other criminal organizations is financial profit. Thus, the enemies of these organizations are any political, military, legal, or judicial institutions that impede their actions and interfere with their ability to make a profit. However, there are other groups that conduct drug- trafficking or other illegal actions as a means to purchase weapons and finance other paramilitary activities.

When mutual interests exist, criminal organizations may combine efforts with insurgent and/or guerrilla organizations controlling and operating in the same area. Such allies can provide security and protection or other support to the criminal organization’s activities in exchange for financial assistance, arms, and protection against government forces or other common enemies. The amount of mutual protection depends on the size and sophistication of each organization and the respective level of influence with the government or the local population.

Criminal organizations may conduct civic actions to gain and maintain support of the populace. A grateful public can provide valuable security and support functions. The local citizenry may willingly provide ample intelligence collection, counterintelligence, and security support. Intelligence and security can also be the result of bribery, extortion, or coercion.

Private Security Organizations

Private security organizations (PSOs) are business enterprises or local ad hoc groups that provide security and/or intelligence services, on a contractual or self-interest basis, to protect and preserve a person, facility, or operation. Some PSOs might be transnational corporations. Others might be domestic firms that supply contract guard forces, or they might be local citizen organizations that perform these actions on a volunteer basis. Their clients can include private individuals and businesses (including transnational corporations) or even insurgent or criminal organizations.

The level of sophistication and competence of a commercial PSO is often directly related to a client's ability to pay. For example, a drug organization can afford to pay more than many small countries. The leader of an insurgent or criminal organization might employ a PSO to provide bodyguards or conduct surveillance or a search at a site prior to his arrival. Another group, such as a drug organization or a transnational corporation, may contract a PSO to guard its facilities. During the conduct of their duties, members of a PSO may take offensive actions. For example, a patrol may conduct a small-scale ambush to counter an intrusion. The allegiance of PSOs can vary from fanatical devotion to just doing a job for purely financial reasons. Each organization is tailored to serve its customer’s needs.

Noncombatants

Noncombatants might be friendly, neutral, or hostile toward U.S. forces. Even if they are not hostile, they could get in the way or otherwise affect the ability of U.S. units to accomplish their METL tasks. Some might become hostile, if U.S. forces do not treat them properly. Noncombatants may be either armed or unarmed.

A military or paramilitary force can manipulate an individual or group of noncombatants by exploiting their weaknesses or supplying their needs. For example, an insurgent, guerrilla, drug, or criminal organization might use bribery or extortion to induce noncombatants to act as couriers or otherwise support its activities. It might also coerce a businessperson into running a front company on its behalf. A paramilitary organization might orchestrate a civil disturbance by encouraging the local populace to meet at a public area at a certain time. Members of the paramilitary group could then infiltrate the crowd and incite it to riot or protest. Sometimes, they might pay members of the local populace to conduct a demonstration or march.

Unarmed Noncombatants

Common types of unarmed noncombatants found in the organizational directories include medical teams, media, humanitarian relief organizations, transnational corporations, local populace, displaced persons, transients, and foreign government and diplomatic personnel. The directories allow for adjusting the number of unarmed noncombatants by employing multiples of the basic organization shown. Thus, numbers can vary from one individual to as many as several hundred. While such noncombatants are normally unarmed, there is always the potential for them to take up arms in reaction to developments in the OE and their perception of U.S. actions. Therefore, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants.

Unarmed noncombatants are likely to be present in any OE. For training in METL tasks other than those dealing with armed conflict, these noncombatants are present as key players. However, armed conflict will draw in more of some groups, such as displaced persons, humanitarian relief organizations, and media. Even in the midst of armed conflict, U.S. units will still need to deal with the local populace and all the other kinds of unarmed noncombatants. Insurgents can melt into the general populace—or perhaps were always part of it.

Armed Noncombatants

There are also likely to be armed noncombatants who are not part of any military or paramilitary organization. Some may be in possession of small arms legally to protect their families or as part of their profession (for example, hunters, security guards, or local police). They may be completely neutral or have leanings for either, or several sides. Some may be affiliated with the one faction or the other, but are not members. Opportunists may decide to hijack a convoy or a vehicle by force of arms. Some are just angry at the United States. Some may be motivated by religious, ethnic, and cultural differences, or by revenge, anger, and greed. The reasons are immaterial—armed noncombatants are ubiquitous. The organizational directories allow for adjusting the number of armed noncombatants by employing multiples of the basic organization shown. Thus, numbers can vary from one individual to as many as several hundred. The armed noncombatants may have vehicles or may not be associated with any vehicle.

Section VI - Exploitation of Noncombatants and Civilian Assets

Some noncombatant personnel and civilian assets may be available as additional resources for Hybrid Threat military and/or paramilitary forces. Because these assets are not part of the peacetime, threat force structure of military or paramilitary organizations, they do not appear under those organizations in the online HTFS organizational directories. In wartime, however, they may be incorporated or co-opted into a military or paramilitary force. Willingly or unwillingly (sometimes unwittingly), such personnel and equipment can supplement the capabilities of a military or paramilitary organization. Therefore, trainers and training planners should also take these assets into account when building a Threat Force Structure.

Military Forces

In wartime, the State and its armed forces might nationalize, mobilize, confiscate, or commandeer civilian transportation assets that are suitable for supporting military operations. These assets can include trucks, boats, or aircraft. The Hybrid Threat would organize these assets into units that resemble their military counterparts as much as possible. For example, civilian trucks and their operators could be formed into a cargo transport company or a whole materiel support battalion. One difference might be that the operators are not armed. This is either because weapons are not available or because the Hybrid Threat does not trust the operators—who may have been coerced into entering this military-like force, along with their vehicles or craft. Civilian construction workers and their equipment (such as dump trucks, back hoes, dozers, and cement mixers) could be formed into an engineer support company or a road and bridge construction company. Medical professionals, engineers, mechanics, and other persons with key skills might also be pressed into military service in wartime, even though they had no connection with the military forces in their peacetime, threat force structure.

Paramilitary Forces

Non-state paramilitary forces also could mobilize additional support assets in the same ways—except for nationalization. Again, they could organize these assets into units or cells that are similar to their counterparts in the particular paramilitary organization. In this case, transport vehicles could include civilian cargo trucks, vans, pickup trucks, automobiles, all-terrain vehicles, motorcycles, bicycles, or carts. For the purposes of a paramilitary organization, transportation assets can extend beyond vehicles and craft to draft animals and noncombatant personnel used as bearers or porters. Individuals might receive pay for their services or the use of their vehicles, or they might be coerced into providing this assistance. A front organization could employ such assets without individuals or vehicle owners being aware of the connection with the paramilitary organization. In other cases, individuals or groups might volunteer their services because they are sympathetic to the cause. When such individuals or their vehicles are no longer required, they melt back into the general populace.

Section VII - Unit Symbols for OPFOR Task Organizations

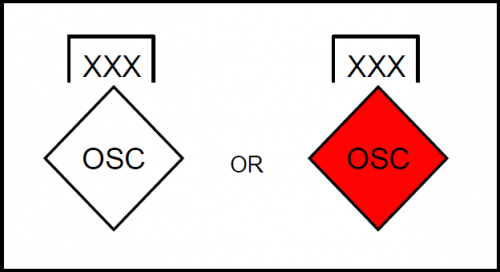

Unit symbols for all OPFOR units employ the diamond-shaped frame specified for “hostile” units in ADRP 1-02. When there is a color capability, the diamond should have red fill color. All Hybrid Threat task organizations should use the “task force” symbol placed over the “echelon” (unit size) modifier above the diamond.

An OSC is the rough equivalent of a U.S. joint task force (JTF). Therefore, the map symbol for an OSC is derived from the JTF symbol in ADRP 1-02 (see figure 3-12.)

At the tactical level, the area inside the diamond contains the symbol for the branch or function of the unit. For Hybrid Threat task organizations, this part of the symbol reflects the type of unit (for example, tank, mechanized infantry, or motorized infantry) in the HTFS, which served as the “base” around which the task organization was formed and whose headquarters serves as the headquarters for the task organization. In many cases, the task organization might also retain the alphanumeric unit designation of that base unit as well. Figures 3-13 through 3-18 provide examples for various types of Hybrid Threat task organizations at the tactical level.

Section VIII - Building an OPFOR Order of Battle

For effective training, a Hybrid Threat must be task-organized to stress those tasks identified in the U.S. unit’s mission essential task list (METL). The U.S. unit commander identifies those areas (or training objectives) requiring a realistic sparring partner. The U.S. unit’s organization and mission drives the task- organizing of the Hybrid Threat. Hybrid Threat task-organizing is accomplished to either stress issues identified in the U.S. unit’s METL or it is accomplished in order to exploit the Hybrid Threat strength and U.S. weakness. Steps 1 through 3 of the process outlined below define the scope and purpose of the training exercise. This sets the stage for Steps 4 through 9, which determine the kind of threat needed to produce the desired training. The entire process results in building the appropriate Threat Force Structure.

Step 1. Determine the Type and Size of U.S. Units

The U.S. commander who acts as the senior trainer (commander of the parent organization of the unit being trained) determines the type and size of unit he wants trained for a specific mission or task. The first step in exercise design is for the senior trainer to determine the exact troop list for the training unit. The senior trainer should identify the task organization of the unit to be trained.

Step 2. Set the Conditions

The senior trainer ensures the unit’s training objectives support it’s approved METL. Each training objective has three parts: task, condition, and standard. The OE—including the OPFOR—is the condition. The exercise planner has the task of actual creating the framework for the exercise and its conditions. For the training scenario, the exercise planner develops reasonable courses of action (COAs) for the U.S. unit and reasonable COAs for the Hybrid Threat consistent with the OE and the 7-100-series. The exercise planner determines the size and type of Threat organizations. The conditions under which U.S. units perform tasks to achieve training objectives include the time of day or night, weather conditions, the type of Threat, the type of terrain, the CBRN environment, the maturity of the theater, and the OE variables in play. During scenario development, all the conditions for the exercise OE are set.

Step 3. Select Army Tactical Tasks

The U.S. commander reviews the Army Universal Task List (AUTL) in FM 7-15. As a catalogue, the AUTL can assist a commander in his METL development process by providing all the collective tasks possible for a tactical unit of company-size and above and staff sections. From the AUTL, the U.S. commander selects specific Army tactical tasks (ARTs) on which he wants to train.

Note. Commanders use the AUTL to extract METL tasks only when there is no current mission training plan (MTP) for that echeloned organization, there is an unrevised MTP to delineate tasks, or the current MTP is incomplete.) The AUTL does not include tasks Army forces perform as part of joint or multinational forces at the operational and strategic levels. Those tasks are included in the Universal Joint Task List (UJTL) (CJCSM 3500.04C).

Step 4. Select OPFOR Countertasks

Trainers and planners select OPFOR countertasks to counter or stress each selected ART for the U.S. unit. Appendix A of TC 7-100.2 provides an “OPFOR Universal Task List.” This is a listing of OPFOR tactical countertasks for various ARTs found in the AUTL. If, for example, the U.S. unit’s METL includes ART 5.1.1 (Overcome Barriers/Obstacles/Mines), the OPFOR countertask would involve creating barriers or obstacles or emplacing mines. If the U.S. unit’s METL includes tasks under ART 4.0 (Air Defense), the OPFOR needs to have aviation units. If the U.S. unit’s METL includes ART 5.3.2 (Conduct NBC [CBRN] Defense), the OPFOR needs to have a CBRN capability. If the U.S. unit’s METL includes counterinsurgency operations, the OPFOR should include insurgents.

Step 5. Determine the Type and Size of Hybrid Threat Units

Trainers and planners select the appropriate type and size of Threat unit or units capable of performing the OPFOR countertasks. The type of Threat unit is determined by the type of capability required for each OPFOR countertask. The size of the Threat organization is determined by the required capability and the size of the U.S. unit(s) being trained.

Step 6. Review the HTFS Organizational Directories

Once the U.S. units and tactical tasks have been matched with OPFOR countertasks and Threat units capable of providing counters to each ART, trainers and planners review the list of units in Threat Force Structure on the Army Training Network (ATN). They review this menu of Threat units to find out what kinds and sizes of Threat units are available in the HTFS, and the options given.

Step 7. Compile the Initial Listing of Hybrid Threat Units for the Task Organization

Trainers and planners compile an initial listing of Hybrid Threat units for the task organization. This initial listing could use one of the two task organization formats provided in ADRP 5-0: outline and matrix.

Step 8. Identify the Base Unit

Trainers and planners again review the Hybrid Threat organizational directories to determine which standard OPFOR unit most closely matches the OPFOR units in the initial task organization list. This Threat unit will become the “base” unit to which modifications are made, converting it into a task organization. (At the tactical level, all Threat task organizations are formed around a “base” unit, using that unit’s headquarters and all or some of its original subordinates as a core to which other Hybrid Threat units are added in order to supply capabilities missing in the original “base” organization.) While the base unit for a task organization is most commonly a ground maneuver unit of a regular military force that does not necessarily have to be the case. (For example, an aviation unit might serve as the base for a task organization that includes infantry units to provide security at its base on the ground.) It is even possible that the base unit for the required task organization might be other than a regular military unit. (For example, an insurgent or guerrilla organization might have a small military unit affiliated with it, as “advisors.”)

Before extracting the “base” unit from the organizational directories, trainers and training planners should determine how much of the organizational detail in the directories they actually need for their particular training exercise or simulation. The directories typically break out subordinate units down to squad-size components. However, some simulations either cannot or do not need to provide that level of resolution. Therefore, trainers and training planners should identify the lowest level of organization that will actually be portrayed. If the only task-organizing involved will be internal to that level of base unit, any internal task-organizing is transparent to the users. However, if any subordinate of that base unit receives assets from outside its immediate higher organization, it might be necessary to first modify the subordinate into a task organization and then roll up the resulting personnel and equipment totals into the totals for the parent organization in the OPFOR OB for the exercise.

Step 9. Construct the Task Organization

Trainers and planners modify the standard Threat baseline unit to become the new task organization. This can involve changes in subordinate units, equipment, and personnel. If training objectives do not require the use of all subordinates shown in a particular organization as it appears in the HTFS, users can omit the subordinate units they do not need. Likewise, users can add other units to the baseline organization in order to create a task organization that is appropriate to training requirements. Users must ensure that the size and composition of the Hybrid Threat is sufficient to meet training objectives and requirements. However, total assets organic to an organization or allocated to it from higher levels should not exceed that which is realistic and appropriate for the training scenario. Skewing the force ratio in either direction negates the value of training. Therefore, specific OBs derived from the organizational directories are subject to approval by the trainers’ Hybrid Threat-validating authority.

The steps for converting a HTFS baseline unit to a task-organized Hybrid Threat are straightforward and simple. Once the units comprising the task-organization have been identified and the HTFS baseline unit has been selected, the following sub-steps are then followed:

- Step 9a. Create folders in to accommodate the files copied and/or modified from those in the HTFS directories using in the process explained below.

- Step 9b. Modify the organizational graphics in the document using graphics. Remove the units not needed in the task organization and add the new ones that are required.

- Step 9c. Modify personnel and equipment charts. Even for those lower-level units that have only a document in the HTFS organizational directories, it is recommended to use a spreadsheet as a tool for rolling up personnel and equipment totals for the modified unit. Update the subordinate units at the tops of the columns on the spreadsheets. Adjust all of the equipment numbers in appropriate rows, by unit columns. Once the new personnel and equipment numbers are updated, transfer the appropriate numbers back to the basic organizational document.

- Step 9d. Adjust equipment tiers, if necessary, to reflect different levels of modernity and capability (see chapter 4).

- Step 9e. Update folders and file paths to reflect the conversion from a HTFS organization to a task-organized unit.

The task-organized detachment, BTG, DTG, or OSC is finished. For detailed instructions on performing Step 9 and its sub-steps, see appendix B.

Step 10. Repeat Steps 4 Through 9 as Necessary

Repeat Step 9 for as many task organizations as are required to perform the OPFOR countertasks. In each case, select a baseline HTFS unit and modify it as necessary.

Training may reveal the need for the U.S. unit to train against other ARTs. If so, trainers and planners must repeat Steps 4 through 9.