Chapter 4: Hybrid Threat Operations

- This page is a section of TC 7-100 Hybrid Threat.

Of the four types of strategic-level courses of action outlined in chapter 3, regional, transition, and adaptive operations are also operational designs. This chapter explores those designs and outlines the Hybrid Threat’s (HT’s) principles of operation against an extraregional power. For more detail, see FM 7-100.1.

Contents

Operational Designs

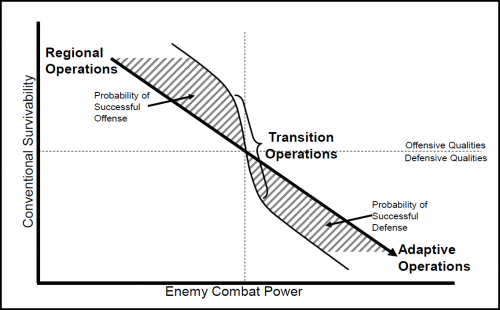

The HT employs three basic operational designs:

- Regional operations. Actions against regional adversaries and internal threats.

- Transition operations. Actions that bridge the gap between regional and adaptive operations and contain some elements of both. The HT continues to pursue its regional goals while dealing with the development of outside intervention with the potential for overmatching the HT’s capabilities.

- Adaptive operations. Actions to preserve the HT’s power and apply it in adaptive ways against overmatching opponents.

Each of these operational designs is the aggregation of the effects of tactical, operational, and strategic actions, in conjunction with the other three instruments of power, that contribute to the accomplishment of strategic goals. The type(s) of operations the HT employs at a given time will depend on the types of threats and opportunities present and other conditions in the operational environment (OE). Figure 4-1 illustrates the HT’s basic conceptual framework for the three operational designs.

Regional Operations

Against opponents from within its region, the HT may conduct “regional operations” with a relatively high probability of success in primarily offensive actions. HT offensive operations are characterized by using all available HT components to saturate the OE with actions designed to disaggregate an opponent’s capability, capacity, and will to resist. These actions will not be limited to attacks on military and security forces, but will affect the entire OE. The opponent will be in a fight for survival across many of the va- riables of the OE: political, military, economic, social, information, and infrastructure.

HT offensive operations seek to—

- Destabilize control.

- Channel actions of populations.

- Degrade key infrastructure.

- Restrict freedom of maneuver.

- Collapse economic relationships.

- Retain initiative.

These operations paralyze those elements of power the opponent possesses that might interfere with the HT’s goals.

The HT may constantly shift which components and sets of components act to affect each variable. For example, regular forces may attack economic targets while criminal elements simultaneously act against an enemy military base or unit in one action, and then in the next action their roles may be re- versed. In another example, information warfare (INFOWAR) assets may attack a national news broadcast one day, a military command and control (C2) network the next day, and a religious gathering a day later. In addition to military, economic, and information aspects of the OE, HT operations may include covert and overt political movements to discredit incumbent governments and serve as a catalyst to influence popular opinion for change. The synergy of these actions creates challenges for opponents of the HT in that it is difficult to pinpoint and isolate specific challenges.

The HT may possess an overmatch in some or all elements of power against regional opponents. It is able to employ that power in an operational design focused on offensive action. A weaker regional neighbor may not actually represent a threat, but rather an opportunity that the HT can exploit. To seize territory or otherwise expand its influence in the region, the HT must destroy a regional enemy’s will and capability to continue the fight. It will attempt to achieve strategic decision or achieve specific regional goals as rapidly as possible, in order to preclude regional alliances or outside intervention.

During regional operations, the HT relies on its continuing strategic operations (see chapter 3) to preclude or control outside intervention. It tries to keep foreign perceptions of its actions during a regional conflict below the threshold that will invite in extraregional forces. The HT wants to achieve its objectives in the regional conflict, but has to be careful how it does so. It works to prevent development of international consensus for intervention and to create doubt among possible participants. Still, at the very outset of regional operations, it lays plans and positions forces to conduct access-limitation operations in the event of outside intervention.

Transition Operations

Transition operations serve as a pivotal point between regional and adaptive operations. The transi- tion may go in either direction. The fact that the HT begins transition operations does not necessarily mean that it must complete the transition from regional to adaptive operations (or vice versa). As conditions allow or dictate, the “transition” could end with the HT conducting the same type of operations as before the shift to transition operations.

The HT conducts transition operations when other regional and/or extraregional forces threaten its ability to continue regional operations in a conventional design against the original regional enemy. At the point of shifting to transition operations, the HT may still have the ability to exert all instruments of power against an overmatched regional enemy. Indeed, it may have already defeated its original adversary.

However, its successful actions in regional operations have prompted either other regional actors or an extraregional actor to contemplate intervention. The HT will use all means necessary to preclude or defeat intervention.

Although the HT would prefer to achieve its strategic goals through regional operations, it has the flexibility to change and adapt if required. Since the HT assumes the possibility of extraregional intervention, its plans will already contain thorough plans for transition operations, as well as adaptive operations, if necessary.

When an extraregional force starts to deploy into the region, the balance of power begins to shift away from the HT. Although the HT may not yet be overmatched, it faces a developing threat it will not be able to handle with normal, “conventional” patterns of operation designed for regional conflict. Therefore, the HT must begin to adapt its operations to the changing threat.

While the HT is in the condition of transition operations, an operational- or tactical-level commander will still receive a mission statement in plans and orders from his higher authority stating the purpose of his actions. To accomplish that purpose and mission, he will use as much as he can of the conventional pat- terns of operation that were available to him during regional operations and as much as he has to of the more adaptive-type approaches dictated by the presence of an extraregional force.

Even extraregional forces may be vulnerable to “conventional” operations during the time they re- quire to build combat power and create support at home for their intervention. Against an extraregional force that either could not fully deploy or has been successfully separated into isolated elements, the HT may still be able to use some of the more conventional patterns of operation. The HT will not shy away from the use of military means against an advanced extraregional opponent so long as the risk is commensurate with potential gains.

Transition operations serve as a means for the HT to retain the initiative and pursue its overall stra- tegic goals. From the outset, one of the HT’s strategic goals would have been to defeat any outside intervention or prevent it from fully materializing. As the HT begins transition operations, its immediate goal is preservation of its instruments of power while seeking to set conditions that will allow it to transition back to regional operations. Transition operations feature a mixture of offensive and defensive actions that help the HT control the tempo while changing the nature of conflict to something for which the intervening force is unprepared. Transition operations can also buy time for the HT’s strategic operations to succeed.

There are two possible outcomes to transition operations. If the extraregional force suffers sufficient losses or for other reasons must withdraw from the region, the HT’s operations may begin to transition back to regional operations, again becoming primarily offensive. If the extraregional force is not compelled to withdraw and continues to build up power in the region, the HT’s transition operations may begin to gravitate in the other direction, toward adaptive operations.

Adaptive Operations

Generally, the HT conducts adaptive operations as a consequence of intervention from outside the region. Once an extraregional force intervenes with sufficient power to overmatch the HT, the full conventional design used in regionally-focused operations is no longer sufficient to deal with this threat. The HT has developed its techniques, organization, capabilities, and strategy with an eye toward dealing with both regional and extraregional opponents. It has already planned how it will adapt to this new and changing threat and has included this adaptability in its methods.

The HT’s immediate goal is survival. However, its long-term goal is still the expansion of influence. In the HT’s view, this goal is only temporarily thwarted by the extraregional intervention. Accordingly, planning for adaptive operations focuses on effects over time. The HT believes that patience is its ally and an enemy of the extraregional force and its intervention in regional affairs.

The HT believes that adaptive operations can lead to several possible outcomes. If the results do not completely resolve the conflict in its favor, they may at least allow it to return to regional operations. Even a stalemate may be a victory, as long as it preserves enough of its instruments of power and lives to fight another day.

When an extraregional power intervenes, the HT has to adapt its patterns of operation. It still has the same forces and technology that were available to it for regional operations, but must use them in creative and adaptive ways. It has already thought through how it will adapt to this new or changing threat in general terms. (See Principles of Operation versus an Extraregional Power, below.) It has already developed appropriate branches and sequels to its core plans and does not have to rely on improvisation. During the course of combat, it will make further adaptations, based on experience and opportunity.

Even with the intervention of an advanced extraregional power, the HT will not cede the initiative. It may employ military means so long as this does not either place its survival at risk or risk depriving it of sufficient force to remain a significant influence in its region after the extraregional intervention is over. The primary objectives are to—

- Preserve power.

- Degrade the enemy’s will and capability to fight.

- Gain time for aggressive strategic operations to succeed.

The HT will seek to conduct adaptive operations in circumstances and terrain that provide opportunities to optimize its own capabilities and degrade those of the enemy. It will employ a force that is optimized for the terrain or for a specific mission. For example, it will use its antitank capability, tied to obstacles and complex terrain, inside a defensive structure designed to absorb the enemy’s momentum and fracture his organizational framework.

The types of adaptive actions that characterize adaptive operations can also serve the HT well in regional or transition operations, at least at the tactical and operational levels. However, once an extraregional force becomes fully involved in the conflict, the HT will conduct adaptive actions more frequently and on a larger scale.

Principles of Operations Versus An Extraregional Power

The HT assumes the distinct possibility of intervention by a major extraregional power in any regional conflict. It views the United States as the most advanced extraregional force it might have to face. Like many other countries and non-state actors, the HT has studied U.S. military forces and their operations and is pursuing lessons learned based on its assessments and perceptions. The HT is therefore using the United States as its baseline for planning adaptive approaches for dealing with the strengths and weaknesses of an extraregional force. It believes that preparing to deal with intervention by U.S. forces will en- able it to deal effectively with those of any other extraregional power. Consequently, it has devised the following principles for applying its various instruments of diplomatic-political, informational, economic, and military power against this type of threat.

Access Limitation

Extraregional enemies capable of achieving overmatch against the HT must first enter the region using power-projection capabilities. Therefore, the HT’s force design and investment strategy is focused on access limitation in order to—

- Selectively deny, delay, and disrupt entry of extraregional forces into the region.

- Force them to keep their operating bases beyond continuous operational reach.

This is the easiest manner of preventing the accumulation of enemy combat power in the region and thus defeating a technologically superior enemy.

Access limitation seeks to affect an extraregional enemy’s ability to introduce forces into the theater. Access-limitation operations do not necessarily have to deny the enemy access entirely. A more realistic goal is to limit or interrupt access into the theater in such a way that the HT’s forces are capable of dealing with them. By limiting the amount of force or the options for force introduction, the HT can create conditions that place its conventional capabilities on a par with those of an extraregional force. Capability is measured in terms of what the enemy can bring to bear in the theater, rather than what the enemy possesses.

The HT’s goal is to limit the enemy’s accumulation of applicable combat power to a level and to lo- cations that do not threaten the accomplishment of the HT’s overall strategic goals. This may occur through many methods. For example, the HT may be able to limit or interrupt the enemy’s deployment through actions against his aerial and sea ports of debarkation (APODs and SPODs) in the region. Hitting such targets also has political and psychological value. The HT will try to disrupt and isolate enemy forces that are in the region or coming into it, so that it can destroy them piecemeal. It might exploit and manipulate international media to paint foreign intervention in a poor light, decrease international resolve, and affect the force mix and rules of engagement (ROE) of the deploying extraregional forces.

Control Tempo

The HT initially employs rapid tempo in an attempt to conclude regional operations before an extraregional force can be introduced. It will also use rapid tempo to set conditions for access-limitation operations before the extraregional force can establish a foothold in the region. Once it has done that, it needs to be able to control the tempo—to ratchet it up or down—as is advantageous to its own operational or tactical plans.

During the initial phases of an extraregional enemy’s entry into the region, the HT’s forces may employ a high operational tempo to take advantage of the weaknesses inherent in enemy power projection. (Lightly equipped forces are usually the first to enter the region.) This may take the form of attack by the HT’s forces against enemy early-entry forces, linked with diplomatic, economic, and informational efforts to terminate the conflict quickly before main enemy forces can be brought to bear. Thus, the HT may be able to force the enemy to conventional closure, rather than needing to conduct adaptive operations later, when overmatched by the enemy.

An extraregional enemy normally tries to slow the tempo while it is deploying into the region and to speed it up again once it has built up overwhelming force superiority. The HT’s forces will try to increase the tempo when the enemy wants to slow it and to slow the tempo at the time when the enemy wants to accelerate it.

By their nature, offensive operations tend to control time or tempo. Defensive operations tend to determine space or location. Through a combination of defensive and offensive actions, the HT’s adaptive operations seek to control both location and tempo.

If the HT cannot end the conflict quickly, it may take steps to slow the tempo and prolong the conflict. This can take advantage of enemy lack of commitment over time. The preferred HT tactics during this period would be those means that avoid decisive combat with superior forces. These activities may not be linked to maneuver or ground objectives. Rather, they may be intended instead to inflict mass casualties or destroy flagship systems, both of which will reduce the enemy’s will to continue the fight.

Cause Politically Unacceptable Casualties

The HT will try to inflict highly visible and embarrassing losses on enemy forces to weaken the enemy’s domestic resolve and national will to sustain the deployment or conflict. Modern wealthy nations have shown an apparent lack of commitment over time. They have also demonstrated sensitivity to domes- tic and world opinion in relation to conflict and seemingly needless casualties. The HT believes it can have a comparative advantage against superior forces because of the collective psyche and will of the HT forces and their leadership to endure hardship or casualties, while the enemy may not be willing to do the same.

The HT also has the advantage of disproportionate interests. The extraregional force may have limited objectives and only casual interest in the conflict, while the HT approaches it from the perspective of total war and the threat to its aspirations or even its survival. The HT is willing to commit all means necessary, for as long as necessary, to achieve its strategic goals. Compared to the extraregional enemy, the HT stands more willing to absorb higher combatant and noncombatant casualties in order to achieve victory. It will try to influence public opinion in the enemy’s homeland to the effect that the goal of intervention is not worth the cost.

Battlefield victory does not always go to the best-trained, best-equipped, and most technologically advanced force. The collective will of a nation-state or non-state organization encompasses a unification of values, morals, and effort among its leadership, its forces, and its individual members. Through this unification, all parties are willing to individually sacrifice for the achievement of the unified goal. The interaction of military actions and other instruments of power, conditioned by collective will, serves to further define and limit the achievable objectives of a conflict for all parties involved. These factors can also deter- mine the duration of a conflict and conditions for its termination.

Neutralize Technological Overmatch

Against an extraregional force, the HT’s forces will forego massed formations, patterned echelonment, and linear operations that would present easy targets for such an enemy. The HT will hide and disperse its forces in areas of sanctuary that limit the enemy’s ability to apply his full range of technological capabilities. However, the HT can rapidly mass forces and fires from those dispersed locations for decisive combat at the time and place of its own choosing.

The HT will attempt to use the physical environment and natural conditions to neutralize or offset the technological advantages of a modern extraregional force. It trains its forces to operate in adverse weather, limited visibility, rugged terrain, and urban environments that shield them from the effects of the enemy’s high-technology weapons and deny the enemy the full benefits of his advanced C2 and reconnaissance, intelligence, surveillance, and target acquisition (RISTA) systems.

The HT can also use the enemy’s robust array of RISTA systems against him. His large numbers of sensors can overwhelm his units’ ability to receive, process, and analyze raw intelligence data and to provide timely and accurate intelligence analysis. The HT can add to this saturation problem by using deception to flood enemy sensors with masses of conflicting information. Conflicting data from different sensors at different levels (such as satellite imagery conflicting with data from unmanned aerial vehicles) can con- fuse the enemy and degrade his situational awareness.

The destruction of high-visibility or unique systems employed by enemy forces offers exponential value in terms of increasing the relative combat power of the HT’s forces. However, these actions are not always linked to military objectives. They also maximize effects in the information and psychological arenas. High-visibility systems that could be identified for destruction could include stealth aircraft, attack helicopters, counterbattery artillery radars, aerial surveillance platforms, or rocket launcher systems. Losses among these premier systems may undermine enemy morale, degrade operational capability, and inhibit employment of these weapon systems.

If available, precision munitions can degrade or eliminate high-technology weaponry. Camouflage, deception, decoy, or mockup systems can degrade the effects of enemy systems. Also, HT forces can employ low-cost GPS jammers to disrupt enemy precision munitions targeting, sensor-to-shooter links, and navigation. Another way to operate on the margins of enemy technology is to maneuver during periods of reduced exposure, those periods identified by a detailed study of enemy capabilities.

Modern militaries rely upon information and information systems to plan and conduct operations. For this reason, the HT will conduct extensive information attacks and other offensive INFOWAR actions. It could physically attack enemy systems and critical C2 nodes, or conduct “soft” attacks by utilizing computer viruses or denial-of-service activities. Attacks can target enemy military and civilian decision makers and key information nodes such as information network switching centers, transportation centers, and aerial platform ground stations. Conversely, HT information systems and procedures should be designed to deny information to the enemy and protect friendly forces and systems with a well-developed defensive INFOWAR plan.

The HT may have access to commercial products to support precision targeting and intelligence analysis. This proliferation of advanced technologies permits organizations to achieve a situational awareness of enemy deployments and force dispositions formerly reserved for selected militaries. Intelligence can also be obtained through greater use of human intelligence (HUMINT) assets that gain intelligence through civilians or local workers contracted by the enemy for base operation purposes. Similarly, technologies such as cellular telephones are becoming more reliable and inexpensive. It is becoming harder to discriminate between use of such systems by civilian and military or paramilitary actors. Therefore, they could act as a primary communications system or a redundant measure of communication, and there is little the enemy can do to prevent their use.

Change the Nature of Conflict

The HT will try to change the nature of conflict to exploit the differences between friendly and enemy capabilities. To do this, it can take advantage of the opportunity afforded by phased deployment by an extragegional enemy. Following an initial period of regionally-focused conventional operations, the HT will change its operations to focus on preserving combat power and exploiting enemy ROE. This change of operations will present the fewest targets possible to the rapidly growing combat power of the enemy. It is possible that enemy power-projection forces, optimized for a certain type of maneuver warfare, would be ill suited to continue operations. (An example would be a heavy-based projection force confronted with combat in complex terrain.)

Against early-entry forces, the HT may still be able to use the design it employed in previous operations against regional opponents. However, as the extraregional force builds up to the point where it threat- ens to overmatch HT forces, the HT is prepared to disperse its forces and employ them in patternless operations that present a battlefield that is difficult for the enemy to analyze and predict.

The HT may hide and disperse its forces in areas of sanctuary. The sanctuary may be physical, often located in urban areas or other complex terrain that limits or degrades the capabilities of enemy systems. However, the HT may also use moral sanctuary by placing its forces in areas shielded by civilians or close to sites that are culturally, politically, economically, or ecologically sensitive. The HT’s forces will defend in sanctuaries, when necessary. However, elements of those forces will move out of sanctuaries and attack when they can create a window of opportunity or when opportunity is presented by physical or natural conditions that limit or degrade the enemy’s systems.

The strengths and weaknesses of an adversary may require other adjustments. The HT will capitalize on interoperability issues among the enemy forces and their allies by conducting rapid actions before the enemy can respond with overwhelming force. If the HT operates near the border of a country with a sympathetic population, it can use border areas to provide refuge or a base of attack for insurgent or other irregular forces. Also, the HT can use terror tactics against enemy civilians or soldiers not directly connected to the intervention as a device to change the fundamental nature of the conflict.

The HT may have different criteria for victory than the extraregional force—a stalemate may be good enough. Similarly, its definition of victory may not require a convincing military performance. For example, it may call for inflicting numerous casualties to the enemy. The HT’s perception of victory may equate to its survival. So the nature of the conflict may be perceived differently in the eyes of the HT versus those of the enemy.

Allow No Sanctuary

The HT seeks to deny enemy forces safe haven during every phase of a deployment and as long as they are in the region. The resultant drain on manpower and resources to provide adequate force-protection measures can reduce the enemy’s strategic, operational, and tactical means to conduct war and erode his national will to sustain conflict.

Along with dispersion, decoys, and deception, the HT uses urban areas and other complex terrain as sanctuary from the effects of enemy forces. Meanwhile, its intent is to deny enemy forces the use of such terrain. This forces the enemy to operate in areas where the HT’s fires and strikes can be more effective.

Terror tactics are one of the effective means to deny sanctuary to enemy forces. Terrorism has a purpose that goes well beyond the act itself. The goal is to generate fear. For the HT, these acts are part of the concept of total war. HT-sponsored or -affiliated terrorists or independent terrorists can attack the enemy anywhere and everywhere. The HT’s special-purpose forces (SPF) can also use terror tactics and are well equipped, armed, and motivated for such missions.

The HT is prepared to attack enemy forces anywhere on the battlefield, at overseas bases, at home stations, and even in military communities. It will attack his airfields, seaports, transportation infrastructures, and lines of communications (LOCs). These attacks feature coordinated operations by all available forces, using not just terror tactics, but possibly long-range missiles and weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Targets include not only enemy military forces, but also contractors and private firms involved in transporting troops and materiel into the region. The goal is to present the enemy with a nonlinear, simultaneous battlefield. Striking such targets will not only deny the enemy sanctuary, but also weaken his national will, particularly if the HT can strike targets in the enemy’s homeland.

Employ Operational Exclusion

The HT will apply operational exclusion to selectively deny an extraregional force the use of or access to operating bases within the region or near it. In doing so, it seeks to delay or preclude military operations by the extraregional force. For example, through diplomacy, economic, or political connections, information campaigns, and/or hostile actions, the HT might seek to deny the enemy the use of bases in other foreign nations. It might also attack population and economic centers for the intimidation effect, using long-range missiles, WMD, or SPF.

Forces originating in the enemy’s homeland must negotiate long and difficult air or surface LOCs merely to reach the region. Therefore, the HT will use any means at its disposal to also strike the enemy forces along routes to the region, at transfer points en route, at aerial and sea ports of embarkation (APOEs and SPOEs), and even at their home stations. These are fragile and convenient targets in support of transition and adaptive operations.

Employ Operational Shielding

The HT will use any means necessary to protect key elements of its combat power from destruction by an extraregional force, particularly by air and missile forces. This protection may come from use of any or all of the following:

- Complex terrain.

- Noncombatants.

- Risk of unacceptable collateral damage.

- Countermeasure systems.

- Dispersion.

- Fortifications.

- INFOWAR.

Operational shielding generally cannot protect the entire force for an extended time period. Rather, the HT will seek to protect selected elements of its forces for enough time to gain the freedom of action necessary to pursue its strategic goals.