DATE: Appendices

Contents

[hide]- 1 Appendix A: Organizational Equipment Tables

- 2 Appendix B: OPFOR Task-Organizing for Combat

- 2.1 OPFOR TASK-ORGANIZING FOR COMBAT

- 2.2 ADMINISTRATIVE FORCE STRUCTURE

- 2.3 BASELINE EQUIPMENT

- 2.4 TASK-ORGANIZING

- 2.4.1 STEPS 1-3: SELECT TRAINING UNITS AND TASKS

- 2.4.2 STEP 4: SELECT OPFOR COUNTERTASKS

- 2.4.3 STEP 5: DETERMINE THE TYPE AND SIZE OF OPFOR UNITS

- 2.4.4 STEP 6: REVIEW THE AFS

- 2.4.5 STEP 7: COMPILE THE INITIAL LISTING OF OPFOR UNITS FOR THE TASK ORGANIZATION

- 2.4.6 STEP 8: IDENTIFY THE BASE UNIT

- 2.4.7 STEP 9: CONSTRUCT THE TASK-ORGANIZED BTG

- 2.4.8 STEP 10: CONSTRUCT THE LOCAL INSURGENT ORGANIZATION

- 2.4.9 STEP 11: CONSTRUCT TASK-ORGANIZED BTG SUBORDINATES

- 2.4.10 STEP 12: REVIEW AND CONSTRUCT OTHER TASK ORGANIZATIONS IF NECESSARY

- 3 Appendix C: OPFOR Equipment Tiers

- 4 Appendix D: Road to War

Appendix A: Organizational Equipment Tables

For detailed examples of OPFOR Organizational equipment, see the tables in the Threat Force Structure section of the ACE-Threats Integration’s Army Training Network webpage, located at https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=311.

Appendix B: OPFOR Task-Organizing for Combat

OPFOR TASK-ORGANIZING FOR COMBAT

The concept of task-organizing for combat is not unique to the OPFOR. It is universal, performed at all levels, and has been around as long as combat. The US Army defines a task organization as “A temporary grouping of forces designed to accomplish a particular mission” and defines task- organizing as “The process of allocating available assets to subordinate commanders and establishing their command and support relationships” (FM 1-02). Task-organizing of the OPFOR must follow OPFOR doctrine (see 7-100 series of FM and TC), reflect requirements for stressing US units’ mission essential task list (METL) in training, and also follow the guidance set forth in TC 7- 101 Exercise Design.

The process of task-organizing for combat and its role in matching the appropriate OPFOR task organization to the training objectives of the unit to be trained is discussed in Chapter 3 of FM 7-100.4 OPFOR Organization Guide. This appendix explains in more detail how trainers and training planners modify an OPFOR organization from the structure listed in the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE) Order of Battle (OB) and the organizational directories in FM 7-100.4 into an OPFOR task organization for countering the tasks listed in FM 7-15, Army Universal Task List (AUTL). For illustrative purposes, this appendix describes a particular example based on hypothetical tasks and OPFOR countertasks. Then, it provides detailed guidance on how to task- organize OPFOR units from the bottom up.

Note: All of the OPFOR organizations listed in the organizational directories are constructed using Microsoft Office® software (MS Word®, MS PowerPoint®, and MS Excel®). The use of these commonly available tools should allow trainers and planners to tailor and/or task-organize units individually or collectively to meet specific training and/or simulation requirements.

ADMINISTRATIVE FORCE STRUCTURE

As stated earlier in the Introduction to Section 4, the countries of Ariana, Atropia, Donovia, Limaria, and Gorgas all have their militaries organized into individual AFS to manage their respective military forces in peacetime. The AFS of each country is the aggregate of various military headquarters, facilities, and installations designed to man, train, equip, and sustain the forces.

In peacetime, forces are commonly grouped into divisions, corps, or armies for administrative purposes. The AFS includes all components of the armed forces-not only regular, standing forces (active component), but also reserve and militia forces (reserve component).

BASELINE EQUIPMENT

The organizational directories in FM 7-100.4 provide example equipment types and the numbers of each type typically found in specific organizations. The purpose is to give trainers and training planners a good idea of what an OPFOR structure should look like. Training requirements, however, may dictate some modifications to this equipment baseline. Therefore, training planners have several options by which they can modify equipment holdings to meet particular training requirements. Often this is effected by simply changing an equipment tier from one level to another.

For each organization in the OPFOR, the online organizational directories list “Principal Items of Equipment” in the basic MS Word® document and/or list “Personnel and Items of Equipment” in an MS Excel® chart. This equipment corresponds to tier 2 in the tier tables of the Worldwide Equipment Guide (WEG). However, some elite units, such as Special-Purpose Forces (SPF), may have tier 1 equipment while insurgents or guerrillas may have tier 3 or 4.

Note: OPFOR equipment is broken into four “tiers” in order to portray systems for adversaries with differing levels of force capabilities for use as representative examples of a rational force developer’s systems mix. Equipment is listed into convenient tier tables for use as a tool for trainers to reflect different levels of modernity. Tier 2 (default OPFOR level) reflects modern competitive systems fielded in significant numbers for the last 10 to 20 years. See WEG Vol 1, Chap 1, and Vol II, Chap 1 for additional information.

TASK-ORGANIZING

Task-organizing is simply the process used to convert peacetime units into their warfighting structure. This appendix describes how each of the five countries must task-organize its forces from its AFS into the appropriate war-fighting orders of battle (ground, air, and naval). In order to properly task-organize, the OPFOR trainers representing each country will analyze their own strengths and weaknesses, as well as those of their enemy. They will also consider how best to counter or mitigate the enemy’s weapons systems (or its capabilities) and/or how to best exploit them to their own advantage. More importantly, however, task-organization ensures the OPFOR meets the training objective. The mitigation or exploitation may be by means of equipment, tactics, or organization—or more likely all of these. However, the process generally starts with the proper task- organization of forces with the proper equipment to facilitate appropriate tactics, techniques, and procedures. The OPFOR trainers must consider where the assets required for a particular task organization are located within the AFS and how to get them allocated to the task organization that needs them, when and where it needs them.

The purpose of task-organizing the OPFOR is to build an OPFOR OB that is appropriate for, and meets all, US training requirements. The OPFOR AFS in Ariana, Atropia, Donovia, Gorgas, and Limaria are not the OPFOR OB. However, once these structures are task-organized, the resulting OB will then become the OPFOR’s go-to-war, fighting force structure.

The last part of chapter 3 in FM 7-100.4 delineates the specific process of creating the properly task- organized OPFOR for an exercise. This appendix provides a summary of the nine-step task- organization process as it is discussed in FM 7-100.4.

STEPS 1-3: SELECT TRAINING UNITS AND TASKS

The nine-step task-organization process begins and ends with the senior commander (commander of the unit to be trained). For training purposes the senior commander will identify what units he wants trained in which selected tasks. For example, if the training units consist of a lightly armored force of two brigade-size units, the commander’s primary training objective may be to conduct an assault and sustained combat to destroy an OPFOR brigade defending in complex terrain. His secondary training objective could be to restore and maintain civil order. Once the senior commander has determined what tasks he wants to train, the lead trainer will develop the countertasks for the OPFOR and its task organization based on the nine-step process. The senior commander then reviews the OPFOR task organization and the countertasks to ensure that his requirements have been met.

The US commander (senior trainer) also reviews FM 7-15 AUTL and determines the specific tactical collective tasks on which he wants to train his unit. The specific Army Tactical Tasks (ARTs) selected from the AUTL for the above example are:

- ART 5.1.1 Overcome Barriers/Obstacles/Mines

- ART 8.1.2 Conduct an Attack

- ART 8.1.3 Exploitation

- ART 8.3.1.2 Conduct Peace Enforcement Operations

- ART 8.3.2.3 Conduct Combat Operations in Support of Foreign Internal Defense (Counter Insurgents and Terrorists)

- ART 8.3.7 Combat Terrorism

Thus, the US commander (senior trainer) has completed Steps 1 through 3 of the process outlined at the end of chapter 3 in FM 7-100.4, which define the scope and purpose of the training exercise. Now the training planners know that the enemy of the OPFOR (the training unit) is lightly armored, mobile, and lethal, and consists of at least two or more brigade-level units. The training commander has determined the level and types of units he wants trained and the specific tasks on which he wants them trained. This sets the stage for Steps 4 through 9, which determine the kind of OPFOR needed to produce the desired training. The entire process results in building the appropriate OPFOR OB that must provide appropriate organizations capable of countering (stressing) those tasks selected from the AUTL.

STEP 4: SELECT OPFOR COUNTERTASKS

The mission of the OPFOR is to counter the training unit, with capabilities that challenge the training unit’s ability to accomplish its tasks. The OPFOR Tactical Task List in TC 7-101 Exercise Design, serves as the primary source for most tasks the OPFOR must perform. Exercise planners reference this list first when conducting countertask analysis. Only if the OPFOR Tactical Task List does not contain an appropriate task is one selected for the OPFOR from the AUTL. In this case, the training unit’s mission is to attack and destroy the OPFOR. Therefore, the OPFOR’s mission is to prevent the training unit (enemy) from destroying the OPFOR and, if possible, destroy the attacking enemy. The OPFOR could accomplish this by defending with light, mobile forces in complex terrain and perhaps employing guerrilla warfare tactics. In the example, the training commander has also selected a task to restore civil order. One way of countering this task is for the OPFOR to possess an organization capable of providing or instigating civil disorder to stress this training. The commander also wants to train against ART 8.3.7 (Combat Terrorism). One way to counter this task is for the OPFOR to include insurgents using terror tactics.

STEP 5: DETERMINE THE TYPE AND SIZE OF OPFOR UNITS

Next, trainers and planners determine the appropriate type and size of OPFOR units capable of performing the OPFOR countertasks and conducting persistent fights on several levels. For the maneuver fight, defending against two brigade-size US units, the OPFOR needs a brigade-size organization. The optimal OPFOR organization for conducting such a defense in complex terrain would include relatively light, motorized infantry, perhaps some even lighter guerrilla forces, and preferably some mechanized infantry, combined with an antiarmor capability against lightly armored US forces. Such a mix of forces would entail the use of a brigade tactical group (BTG) task organization. In addition, a local insurgent force can provide the training unit with an opportunity to combat terrorism.

Motorized Infantry Forces

The OPFOR organization determined to best counter (stress) the ARTs mentioned above consists of a BTG based on a motorized infantry brigade, with an antiarmor capability against lightly armored forces to counter the maneuver fight, and an affiliated local insurgent organization to counter ART 8.3.7, Combat Terrorism. The BTG also can have guerrilla and special-purposes forces subordinate to it.

Guerrilla Forces

The BTG could include a guerrilla battalion to provide a wider training spectrum and a realistic training experience. Guerrilla warfare is one of many threats, but it does not necessarily occur in isolation from other threats. While guerrilla organizations can be completely independent of a parent insurgent organization, they are often either a part of the overall insurgency or affiliated with the insurgent groups. Guerrilla units can also be subordinate to a larger, more conventional force. For purposes of illustration and simplicity, in this example the guerrilla battalion is subordinated to the larger conventional maneuver force, the BTG. The guerrillas are a tier 3 and 4 organization. (Equipment tiering is discussed in chapter 4 of FM 7-100.4.) The inclusion of guerrillas provides countertasks to the following ARTs:

- ART 8.3.1.2 Conduct Peace Enforcement Operations

- ART 8.3.2.3 Conduct Combat Operations in Support of Foreign Internal Defense (Counter Insurgents and Terrorists)

When the guerilla battalion is organized for combat with guerrilla hunter-killer companies (H/K) it also fights unconventionally, but with H/K groups, sections, and teams. The task-organized, lethal H/K team structure is ideal for dispersed combat such as fighting in built-up areas, especially urban combat. Complete battalions and brigades—or any part thereof—can be organized for combat as H/K units.

Special-Purpose Forces

Special-purpose forces (SPF) can bring another dimension to the training environment. Therefore, the BTG could integrate an SPF company and an SPF deep attack/reconnaissance platoon into its task organization. The SPF units are a tier 1 (modern) force multiplier providing a completely different level and style of OPFOR countertasks to the fight. While SPF units can also be independent of maneuver forces on the battlefield, and generally are, they can also be subordinate to a maneuver organization. For simplicity, this example has the SPF units subordinate to a parent maneuver organization—the BTG. The inclusion of the SPF provides countertasks to the following ARTs:

- ART 8.3.1.2 Conduct Peace Enforcement Operations

- ART 8.3.2.3 Conduct Combat Operations in support of Foreign Internal Defense (Counter Insurgents and Terrorists)

Note. Force structures for SPF units can be found in FM 7-100.4 OPFOR Organizational Guide, Volume II.

Insurgent Forces

Insurgent forces can provide an OPFOR countertask capability to ART 8.3.7 (Combat Terrorism). A typical insurgent organization also provides the OPFOR with an information warfare (INFOWAR) capability to stress ART 7.10.3 (Maintain Community Relations), which is an implied task inherent to several selected ARTs. Even a local insurgent organization provides a wide spectrum of insurgent capabilities. It is complete with direct action cells, INFOWAR cells, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), IED factories, suicide bombers, and even weapons of mass destruction. The relationship between the BTG and the local insurgent organization, in this example, is one of loose affiliation rather than subordination.

Overall OPFOR Organization

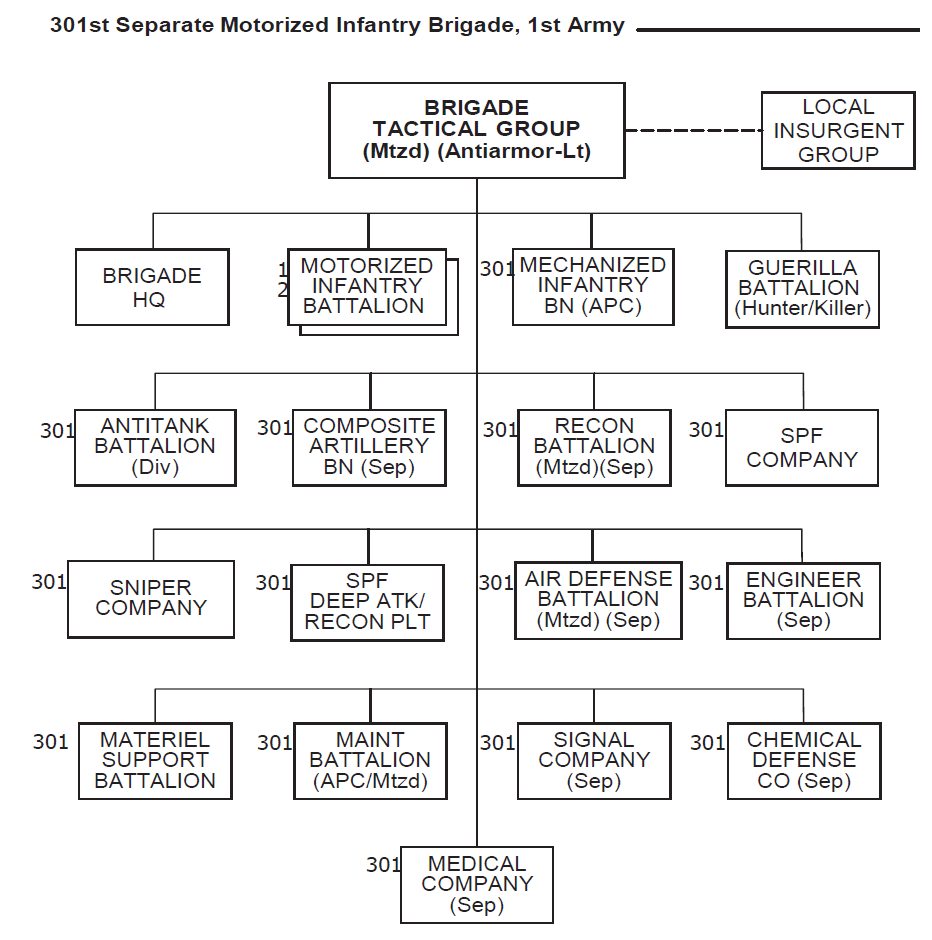

In this example case, the appropriate OPFOR required to meet the commander’s training requirements consists of two parts: the Brigade Tactical Group (Motorized) (Antiarmor-Light) and an affiliated Local Insurgent Organization.

STEP 6: REVIEW THE AFS

The trainers and planners review the list of units in the DATE OB for that particular country and the OPFOR organizational directories in FM 7-100.4 to determine what kinds and sizes of units are available in the country’s AFS. At this point, the purpose is only to review the menu of options available.

STEP 7: COMPILE THE INITIAL LISTING OF OPFOR UNITS FOR THE TASK ORGANIZATION

From the AFS menu, trainers and planners compile an initial listing of OPFOR units for the task organization. At this point, the purpose is only to identify the units available, without concern for any higher-level command to which they are subordinate in the AFS.

STEP 8: IDENTIFY THE BASE UNIT

Trainers and planners again review the OPFOR organizational directories to determine which standard OPFOR unit most closely matches the OPFOR units in the initial task-organization list. This OPFOR unit will become the “base” unit to which modifications are made, converting it into a task organization.

Separate Motorized Infantry Brigade

For the main maneuver force in the above example, the leading candidate seems to be a motorized infantry brigade, of which the organizational directories show two types: divisional and separate. Of the two, the separate motorized infantry brigade has a much more robust antiarmor capability, with an antitank battalion of the type normally found in a division. The separate brigade also has more robust logistics support, which provides better combat sustainability. As a base unit, this brigade can easily accommodate guerrillas and SPF into its task organization to meet training requirements.

To prepare for the task-organizing process, the separate motorized infantry brigade is extracted, exactly as posted, from the AFS organizational directories (see figure below). This AFS brigade will serve as the base (core) that will be modified and built upon to create the task-organized Brigade Tactical Group (Motorized) (Antiarmor-Light) seen on page 4-B-9.

Some units originally subordinate to the separate motorized brigade will be transferred out of the base structure, since they are not needed. Meanwhile, other units that were not part of the base unit will be added in order to provide additional capabilities that are required. From the OPFOR perspective, higher headquarters determines where these units are allocated to or from. If the next higher headquarters does not have a subordinate unit that it can allocate for the task organization, it passes the requirement to (or through) its next higher headquarters until the appropriate unit can be allocated.

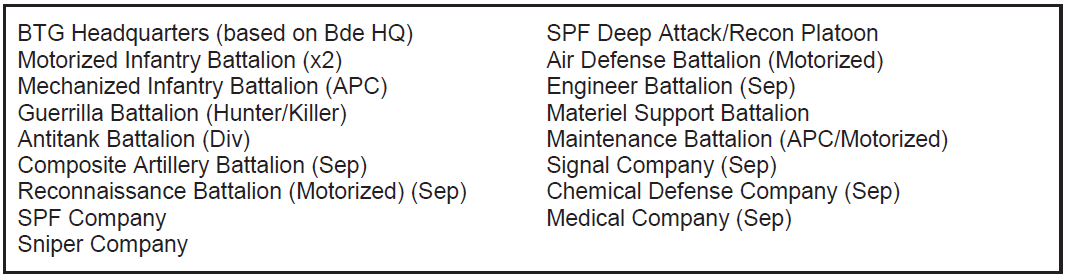

The separate motorized infantry brigade already contains many of the units required for the BTG (Mtzd) (Antiarmor-Lt) task organization. The task-organizing process has determined that the BTG consists of the specific units listed below.Note. For simplicity, all of the units forming the BTG task organization in this example are constituent to the BTG. The local insurgent group is affiliated with the BTG, but it is not part of the BTG. For additional information on command relationships see chapter 3 of FM 7-100.4. Also see chapter 2 of FM 7-100.4 for an explanation of the “(Div)” and “(Sep)” designations following the names of some units (usually battalions or companies).

Note. In this example, again for the sake of simplicity, none of the battalions or companies in the BTG have been task-organized into detachments. In reality, such task-organizing of subordinate units could very well be required in order to produce the right challenge to the training unit’s METL. In that case, training planners creating the OPFOR OB would have to start from the bottom up—first creating the necessary task organizations at the lowest levels of organization and then rolling them up into the personnel and equipment totals for the overall task organization. For example, rather than exchanging its original sniper platoon for a sniper company, the brigade becoming a BTG could have received a standard sniper company and then added its own sniper platoon to that company to create an augmented company-size detachment (CDET). See the Building from the Bottom Up section later in this appendix.

Local Insurgent Organization

The organizational directories of FM 7-100.4 include a “typical” local insurgent organization (see figure on the following page). This baseline organization shows the various types of cells often found in insurgent organizations. However, the dashed boxes in the organizational chart indicate possible variations in the numbers of cells of each type that might be present in a particular insurgent organization. These cell types represent the various functions that can contribute to the OPFOR countertasks in this example.

STEP 9: CONSTRUCT THE TASK-ORGANIZED BTG

There are several differences between the final task-organized BTG (Mtzd) (Antiarmor-Lt) and the AFS separate motorized infantry brigade. Not all units originally subordinate to a standard separate motorized infantry brigade will be needed to complete the task organization, while additional units will be added to provide countertasks to the selected ARTs. Higher headquarters will allocate or re- allocate units depending on its need in the task-organized unit. In this task-organizing process, the AFS separate motorized infantry brigade:

- Loses the two tank battalions, which are transferred back to higher headquarters and possibly allocated to another task organization.

- Loses one motorized infantry battalion, which is transferred back to higher headquarters and possibly allocated to another task organization.

The task-organized BTG:

- Gains a mechanized infantry battalion (APC) in lieu of the one motorized infantry battalion. This battalion was allocated from a mechanized infantry brigade subordinate to the same higher headquarters.

- Gains a guerrilla battalion (hunter/killer). This battalion was probably subordinate to an insurgent organization operating in the area but, by mutual agreement between the higher headquarters of the guerrilla battalion and that of the BTG, has been made subordinate to the BTG only for the duration of the mission for which this task organization was created.

- Gains an SPF company. This company, originally part of a larger SPF organization, was allocated through higher headquarters.

- Upgrades from a sniper platoon to a sniper company. The upgrade was allocated by higher headquarters from a division that is also subordinate to the same higher headquarters. In turn, that division might receive the sniper platoon that was originally part of the separate motorized infantry brigade.

- Gains an SPF deep attack/reconnaissance platoon. This platoon was originally part of a larger SPF organization and was allocated through higher headquarters.

STEP 10: CONSTRUCT THE LOCAL INSURGENT ORGANIZATION

One key difference is that insurgent organizations are irregular forces, meaning that there is no “regular” table of organization and equipment. There is no “standard” structure for an insurgent organization. Thus, the baseline insurgent organizations in the organizational directories of FM 7- 100.4 represent only the “default setting” for a “typical” insurgent organization. The organizational graphic for a “typical” local insurgent organization (see figure on page 4-B-8) therefore includes several dashed boxes indicating the possibility of different multiples of the basic cell types. The baseline organizational charts and lists of personnel and equipment include many “notes” on possible variations in organization or in numbers of people or equipment within a given organization.

When developing an OB for a specific insurgent organization for use in training, training planners need to take several things into consideration:

- What functions the insurgents need to be able to perform

- What equipment is needed to perform those functions

- How many people are required to employ the required equipment

- The number of vehicles in relation to the people needed to drive them or the people and equipment that must be transported

- Equipment associated with other equipment (for example, an aiming circle/goniometer used with a mortar or a day/night observation scope used with a sniper rifle)

When task-organizing insurgent organizations, guerrilla units might be subordinate to a larger insurgent organization, or they might be loosely affiliated with an insurgent organization of which they are not a part. A guerrilla unit or other insurgent organization might be temporarily subordinated to or affiliated with a regular military organization.

BUILDING FROM THE BOTTOM UP

For the sake of simplicity, the BTG (Mtzd) (Antiarmor-Lt) example above did not include any task organizations below the BTG level. In reality, however, it may be necessary to task-organize at lower levels in order to achieve the desired challenges to the training unit. If all units in an OB come straight out of the DATE OB or the FM 7-100.4 organizational directories with no modifications, that OB probably does not portray adequately the OPFOR’s ability to organize its forces adaptively to achieve the optimal effect. (See FM 7-100.4 chapter 3.)

Training planners need to start at the very bottom to look for places where task-organizing is appropriate to the training requirements. At whatever organizational level the need for a task organization is identified, they must make the appropriate modifications to personnel, equipment, and organization charts. Then they must roll up the personnel and equipment to the place in the OB where the higher-level headquarters has received no assets from outside its own original organization—thus, it is not a detachment or a tactical group, but has the same name given to it in the peacetime organizational structure.

STEP 11: CONSTRUCT TASK-ORGANIZED BTG SUBORDINATES

The same basic procedures used in the BTG example in the first part of this appendix also apply to the creation of lower-level task organizations. One difference is that many organizations below brigade level do not have an MS Excel® chart in the organizational directories of FM 7-100.4. Instead, they list personnel and equipment numbers as part of the basic MS Word® document for the organization in question. If training planners task-organize any of these lower-level units, however, it is recommended to use Excel® charts as a tool to keep things straight when rolling up modified personnel and equipment numbers into each successive higher organization.

Adjustments, and/or modification, to the existing organizations and equipment charts are uncomplicated and easy to make, as long as they are accomplished one at a time and remain bite- size. Otherwise, the trainer making the changes might easily become completely overwhelmed and lost in the process.

STEP 12: REVIEW AND CONSTRUCT OTHER TASK ORGANIZATIONS IF NECESSARY

Training planners then review the completed task organizations to ensure they are sufficient to meet training requirements. If they do not, the building process begins again. The training planners start again at the lowest level in any other part of the OB that requires a task organization. Again, they build up to the place where the higher headquarters has received no assets from outside its own original organization and would still have the same name. They repeat this process for as many “branches” of the organizational “tree” as needed to complete the task organization.

Appendix C: OPFOR Equipment Tiers

OPFOR equipment is broken into four “tiers” in order to portray systems for adversaries with differing levels of force capabilities for use as representative examples of a rational force developer’s systems mix. Equipment is listed in convenient tier tables for use as a tool for trainers to reflect different levels of modernity. The tier tables listed below reflect these differing levels of capability. Tier 2 (default OPFOR level) reflects modern competitive systems fielded in significant numbers for the last 10 to 20 years.

Systems reflect specific capability mixes that require specific systems data for portrayal in all US training (live, virtual, and constructive). The OPFOR organization contains a mix of systems in each tier and functional area that realistically vary in fielded age and generation. The tiers are less about the age of the system than they are about realistically reflecting capabilities to be mirrored in training. Systems and functional areas are not modernized equally and simultaneously. Forces have systems and materiel varying 10 to 30 years in age in a functional area. Often military forces emphasize upgrades in one functional area while neglecting upgrades in other functional areas. Force designers may also draw systems from other organization echelons by employing them at higher or lower echelons to supplement those organizations. Below is the general guidance concerning OPFOR equipment tiers (capability):

- Tier 1 reflects a major military force with fielded state-of-the-art technology across functional areas in 2015. At tier 1, new or upgraded systems are robust systems with at least limited fielding in military forces and marketed for sale, with capabilities and vulnerabilities of respective systems to be portrayed in training.

- Tier 2 reflects modern competitive systems fielded in significant numbers for the last 10 to 20 years, with limitations or vulnerabilities being diminished by available upgrades. Although tier 2 forces are equipped for operations in all terrains and can fight day and night, their capability in range and speed for several key systems may be marginally inferior to US capability.

- Tier 3 systems date back generally 30 to 40 years. They have limitations in all three subsystems categories: mobility, survivability, and lethality. Systems and force integration are inferior. However, guns, missiles, and munitions can still challenge vulnerabilities of US forces. Niche upgrades can provide synergistic and adaptive increases in force effectiveness.

- Tier 4 systems reflect 40 to 50 year-old systems, some of which have been upgraded numerous times. These represent Third World or less developed countries’ forces. Use of effective strategy, adaptive tactics, niche technologies, and terrain limitations could enable a Tier 4 OPFOR to challenge US force effectiveness in achieving its goals. The tier includes militia, guerrillas, special police, and other forces, possibly to include some regular forces.

Note. No force in the world has all systems at the most modern tier. Even the best force in the world has a mix of state-of-the-art (tier 1) systems, as well as mature (tier 2), and somewhat dated (tier 3) legacy systems. Modern systems recently purchased may be considerably less than state-of-the-art, due to budget constraints and limited user training and maintenance capabilities. Thus, even new systems may not exhibit tier 1 or tier 2 capabilities. As later forces field systems with emerging technologies, legacy systems may be employed to be more suitable, may be upgraded, and continue to be competitive. Adversaries with lower tier systems will use adaptive technologies and tactics, or obtain niche technology systems to challenge advantages of a modern force.

The tier tables below are listed by their respective volume. Volume I includes Ground Systems while Volume II includes Airspace and Air Defense Systems. These tiers were extracted from the December 2014 Worldwide Equipment Guide (WEG). For additional information and specifics on OPFOR tiers see the 2014 WEG Volume 1, Chapter 1, and Volume II, Chapter 1.

Volume 1: Ground Forces

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | Tier 4 | |

| Dismounted Infantry | ||||

| Infantry Flame Launcher | (Shmel) RPO-M | RPO-A | RPO | LPO-50 |

| Lt AT Disposable Launcher | Armbrust | Armbrust | Armbrust | RPG-18; M72 LAW |

| AT Disposable Launcher | RPG-30/32/28 | RPG-27 | RPG-26 | RPG-22 |

| AT Grenade Lcher (ATGL) | Panzerfaust 3-IT600 | Panzerfaust 3 T-600; RPG-29 | Carl Gustaf M3 | RPG-7V |

| Long-Range ATGL | PF-98 Mounted/Tripod (@ Bn) | RPG-29/Mounted/Tripod | SPG-9M (Imp) | SPG-9 |

| Heavy ATGM Man-Portable | Eryx SR-ATGM | Eryx SR-ATGM | M79/Type 65-1 Recoilless | M67 Recoilless Rifle |

| Light Auto Grenade Launcher | QLZ-87 (Light Configuration); QLZ-87B | W-87 | W-87 | W-87 |

| Auto Grenade Launcher | CIS-40 w/Air-Burst Munitions/ AGS-30; QLZ-87 (Heavy

Configuration) |

AGS-17 | AGS-17 | AGS-17 |

| Heavy Machine Gun | KORD | NSV | NSV | DShk; M2 Browning |

| General Purpose MG | PKM Pechneg | PKM | PKM | PKM |

| Anti-Materiel Rifle | M107A1( .50 Cal); 6S8 and 6S8-1 (12.7mm) | M82A1( .50 Cal); OSV-96 (12.7mm) | M82A1( .50 Cal) | M82A1( .50 Cal) |

| Sniper Rifle | SVD | SVD | SVD | Mosin-Nagant |

| Assault Rifle | AK-74M | AK-74M | AKM | AKM |

| Carbine | AKS-74U | AKS-74U | AK-47 Krinkov | AK-47 Krinkov |

| Company-Dismount ATGM | Spike-LR ATGM Launcher | Spike-MR ATGM Launcher | AT-13 | AT-7 |

| Battalion-Dismount ATGMs | Kornet-E Launcher (1 team) Starstreak-SL AD/AT (1 team) | Kornet-E ATGM Lchr | AT-5B | AT-5 |

| Combat Vehicles | ||||

| Infantry Fighting Vehicle | BMP-2M Berezhok | BMP-2M | AMX-10P | BMP-1PG |

| Infantry IFSV for IFV | BMP-2M Berezhok | BMP-2M w/Kornet/SA-18 | AMX-10 w/AT-5B/SA-16 | BMP-1PG w/ AT-5/SA-16 |

| Amphibious IFV | BMP-3UAE/AT-10B | BMP-3UAE/AT-10B | BMD-2/AT-5B | BMP-1PG/AT-5 |

| Amphibious IFV IFSV | BMP-3UAE/AT-10B | BMP-3UAE/AT-10B | BMD-2/AT-5B | BMD-1PG w/AT-5/SA-16 |

| Armored Personnel Carrier | BTR-3E1/AT-5B | BTR-80A | BTR-80 | M113A1 |

| Amphibious APC | BTR-90 | BTR-80A | WZ-551 | VTT-323 |

| Amphibious APC IFSV | BTR-90/AT-5B/SA-24 | BTR-80A w/Kornet-E/SA-18 | WZ-551 w/AT-5B/SA-16 | VTT-323 w/AT-3C/SA-14 |

| Airborne IFV | BMD-3 | BMD-3 | BMD-2 | BMD-1P |

| Airborne APC | BTR-D | BTR-D | BTR-D | BTR-D |

| Airborne APC IFSV | BTR-D w/Kornet-E, SA-24 | BTR-D w/Kornet-E/SA-18 | BTR-D w/AT-5B/SA-16 | BTR-D w/AT-5, SA-14 |

| Heavy IFV/Heavy IFSV | BMP-3M/w Kornet-E, SA-24 | BMP-3UAE/Kornet-E, SA-18 | Marder 1A1/MILAN 2, SA-16 | BMP-1PG/w SA-14 |

| Combat Recon Vehicle | BRM-3K/Kredo M1 | BRM-3K | BRM-1K | EE-9 |

| Abn/Amphib Recon CRV | BMD-3/Kredo M1 | BMD-3K | BMD-1PK | BMD-1K |

| Armored Scout Car | BRDM-2M-98/Zbik-A | BRDM-2 M-97/Zbik-B | Fox | BRDM-2 |

| Sensor Recon Vehicle | HJ-62C | HJ-62C | BRM-1K | BRM-1K |

| AT Recon Vehicle | PRP-4MU (w/Kredo-M1) | PRP-4M (w/PSNR-5M) | PRP-4 (w/PSNR-5K) | PRP-3 (w/SMALL FRED) |

| Armored Command Vehicle | BMP-1KshM | BMP-1KShM | BMP-1KSh | BMP-1KSh |

| Abn/Amphib ACV | BMD-1KShM | BMD-1KShM | BMD-1KShM | 1KShM |

| Wheeled ACV | BTR-80/Kushetka-B | BTR-80/Kushetka-B | BTR-60PU/BTR-145BM | BTR-60PU/BTR-145BM |

| Combat Support Vehicles | ||||

| Motorcycle | Gear-Up (2-man) | Gear-Up (2-man) | Motorcycle (2-man) | Motorcycle (2-man) |

| Tactical Utility Vehicle | VBL MK2 | VBL | UAZ-469 | UAZ-469 |

| Armored Multi-purpose | MT-LB6MB | MT-LB6MA | MT-LBu | MT-LB |

| All Terrain-Vehicle | Supacat | Supacat | LUAZ-967M | LUAZ-967M |

| Tanks and AT Vehicles | ||||

| Main Battle Tank | T-90A | T-72BU / T-90S | Chieftain | T-55AM |

| Amphibious Tank | Type 63A | Type 63 | M1985 | PT-76B |

| Tracked Heavy Armored CV | 2S25 | AMX-10 PAC 90 | AMX-13 | M41A3 |

| Wheeled Heavy Armored CV | AMX-10RC Desert Storm | AMX-10RC | EE-9 | EE-9 |

| Div ATGM Launcher Vehicle | 9P157-2/Krizantema-S | 9P149 w/AT-9 Ataka | 9P149 w/AT-6 | 9P148/AT-5 |

| Bde ATGM Veh Tracked | 9P162 w/Kornet | AMX-10 HOT 3 | AMX-10 HOT 2 | Type 85/Red Arrow-8A |

| Bde ATGM Veh Wheeled | VBL MK2 w/Kvartet, Kornet | VBL w/Kvartet, Kornet | 9P148/AT-5B | Jeep/Red Arrow-8A |

| Abn ATGM Launcher Veh | VBL MK2 w/Kvartet, Kornet | VBL w/Kvartet, Kornet | BMD-2 with AT-5B | BMD-1P with AT-5 |

| Hvy ATGM Launcher Veh | Mokopa | 9P149 w/Ataka | 9P149 w/AT-6 | 9P148/AT-5 |

| NLOS ATGM Launcher Veh | Nimrod-3 | Nimrod | -- | -- |

| Div Towed AT Gun | 2A45MR | 2A45M | MT-12 | MT-12 |

| Bde Towed AT Gun | 2A45MR | MT-12R | MT-12 | M40A1 |

| Artillery | ||||

| Mortar/Combo Gun Tracked | 2S9-1 | 2S9-1 | 2S9-1 | M106A2 |

| Mortar/Combo Gun Wheeled | 2S23 | 2S23 | 2S12 | M-1943 |

| Towed Mortar or Combo Gun | Type 86 or 2B16 | Type 86 or 2B16 | M75 or MO-120-RT | M-1943 |

| 82-mm Mortar | Type 84 | Type 84 | Type 69 | M-1937 |

| 82-mm Auto Mortar | 2B9 | 2B9 | 2B9 | 2B14-1 |

| 60-mm Mortar | Type 90 | Type 90 | Type 63-1 | Type 63-1 |

| Towed Light Howitzer | D-30 | D-30 | D-30 | D-30 |

| Towed Medium How/Gun | G5 | 2A65 | 2A36 | D-20 |

| Self-Propelled Howitzer | 2S19M1-155, G6, AU-F1T | G6, 2S19M1 | 2S3M1 | 2S3M |

| Multiple Rocket Launcher | 9A51/Prima | 9A51/Prima | BM-21-1 | BM-21 |

| Light MRL/Vehicle Mount | Type 63-1 | Type 63-1 | Type 63-1 | Type 63 |

| Heavy MRL | 9A52-2 and 9P140 | 9A52-2 and 9P140 | 9P140 | Fadjr-3 |

| 1-Round Rocket Launcher | 9P132 | 9P132 | 9P132 | 9P132 |

| Amphibious SP How | 2S1M | 2S1M | 2S1 | 2S1 |

| Artillery Cmd Recon Veh | 1V13M w/1D15, 1V119 | 1V13M w/1D15, 1V119 | 1V13, 1V119 | 1V18/19, 1V110 |

| ACRV, Wheeled | 1V152, 1V110 | 1V152, 1V119, 1V110 | 1V119, 1V110 | 1V18/19, 1V110 |

| Mobile Recon Vehicle | PRP-4MU (w/Kredo-M1) | PRP-4M (w/PSNR-5M) | PRP-4 (w/PSNR-5K) | PRP-3 (w/SMALL FRED) |

| Arty Locating Radar | 1L-259U, 1L-219 | 1L-220U, 1L-219 | ARK-1M | Cymbeline |

| Sound Ranging System | SORAS 6 | SORAS 6 | AZK-7 | AZK-5 |

| Flame Weapon | TOS-1 | TOS-1 | Type 762 MRL | OT-55 Flame Tank |

| Reconnaissance | ||||

| Ground Surveillance Radar | Kredo-1E | Kredo-M1 | PSNR-5M/Kredo-M | PSNR-5/TALL MIKE/Kredo |

| Man-portable Radar | FARA-1E | FARA-1E | N/A | N/A |

| Unattended Ground Sensors | BSA Digital Net | BSA Digital Net | N/A | N/A |

| Remote TV/IR Monitor | Sirene IR | Sosna | N/A | N/A |

| Thermal Night Viewer | Sophie LR | Sophie/NVG 2 Gen II | NVG 2 Gen II | NVG 1Gen II |

| Laser Target Designator | DHY-307 | DHY-307 | 1D15 | -- |

| Laser Rangefinder/Gonio- meter Fire Control System | Vector/SG12 with Sophie-LR | Vector/SG12 with Sophie | PAB-2M | PAB-2 |

| Communications | ||||

| Radio VHF, Hand-Held | Panther-P | TRC5102 | ACH42 | R31K |

| Radio, SPF | Scimitar-H | PRC138 | PVS5300 | PRC104 |

| Radio VHF, Veh Medium Pwr | Panther | Jaguar-V | R163-50U | R173M |

| Radio HF/VHF, Veh Med Pwr | M3TR | RF5000 | XK2000 | R123M |

| Satellite Systems | Syracuse-III | Feng Huo-1 | Mayak | Molinya 1 |

| Global Navigation Satellite | NAVSTAR | GLONASS | Beidou | Galileo |

| Operational Comms | RL402A | R423-1 | KSR8 | R161-5 |

| Tac Wide Area Network | EriTac | RITA | N/A | N/A |

| IBMS Network | Pakistani IBMS | Pakistani IBMS | N/A | N/A |

| Electronic Warfare | ||||

| Ground-Based ESM | Meerkat-S | Weasel 2000 | MCS90 Tamara | R-703/709 |

| Ground-Based EA | CICADA-C | TRC 274 | Pelena-6 | R-330 T/B |

| TACSAT EA | CICADA-R | GSY 1800 | Liman P2 | R-934B |

| Radar EA | BOQ-X300 | CBJ-40 Bome | Pelena-1 | SPN-2/4 |

| GPS EA | Aviaconversia TDS | Optima III | Aviaconversia | -- |

| UAV-Based EA | Fox TX/Barrage | ASN-207/JN-1102 | Yastreb-2MB/AJ-045A | Muecke/Hummel |

| Engineer Systems | ||||

| Wheeled Minelaying Systems | PMZ-4 | PMR-3 | Istrice VS-MTLU-1 | -- |

| Tracked Minelaying Systems | GMZ-3 | GMZ-2 | GMZ | -- |

| Scatterable Mine Systems | PKM Man-Portable Minelayer | UMZ | Istrice VS-MTLU-1 | -- |

| Route Recon Systems | IPR | IRM | -- | -- |

| Route Clearing Systems | IMR-2M | IMR-2 | BAT-2 | BAT-M |

| Bridging Systems | TMM | PMP Pontoon Bridge | MT-55A | -- |

Volume 2: Airspace and Air Defense Systems

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | Tier 4 | |

| Fixed Wing Aircraft | ||||

| Fighter/Interceptor | Su-35 | Su-27SM | Mirage III, MiG-23M | J-7/FISHBED |

| High Altitude Interceptor | MiG-31BS | MiG-25PD | MiG-25 | -- |

| Ground Attack | Su-39 | Su-25TM | Su-25 | Su-17 |

| Multi-Role Aircraft | Su-30MKK | Su-30, Mirage 2000, Tornado IDS | Mirage F1, SU-24 | MiG-21M |

| Bomber Aircraft | Tu-22M3/BACKFIRE-C | Tu-22M3/BACKFIRE-C | Tu-95MS6/BEAR-H | Tu-95S/BEAR-A |

| Command & Control | IL-76/MAINSTAY | IL-76/MAINSTAY | IL-22/COOT-B | IL-22/COOT-B |

| Heavy Transport | IL-76 | IL-76 | IL-18 | IL-18 |

| Medium Transport | AN-12 | AN-12 | AN-12 | AN-12 |

| Short Haul Transport | AN-26 | AN-26 | AN-26 | AN-26 |

| RW Aircraft | ||||

| Attack Helicopter | AH-1W/Supercobra | Mi-35M2 | HIND-F | HIND-D |

| Multi-role Helicopter | Z-9/WZ-9 | Battlefield Lynx | Lynx AH.Mk 1 | Mi-2/HOPLITE |

| Light Helicopter | GAZELLE/SA 342M | GAZELLE/SA 342M | BO-105 | MD-500M |

| Medium Helicopter | Mi-17-V7 | Mi-171V/Mi-171Sh | Mi-8(Trans/HIP-E Aslt) | Mi-8T/HIP-C |

| Transport Helicopter | Mi-26 | Mi-26 | Mi-6 | Mi-6 |

| Other Aircraft | ||||

| Wide Area Recon Helicopter | Horizon (Cougar heli) | Horizon (Cougar heli) | ||

| NBC Recon Heli | HIND-G1 | HIND-G1 | HIND-G1 | -- |

| Jamming Helicopter | HIP-J/K | HIP-J/K | HIP-J/K | HIP-J/K |

| Naval Helicopter | Z-9C | Ka-27/HELIX | Ka-27/HELIX | -- |

| Op-Tactical Recon FW | Su-24MR/FENCER-E | Su-24MR/FENCER-E | IL-20M/COOT | -- |

| EW Intel/Jam FM | Su-24MP/FENCER-E | Su-24MP/FENCER-E | IL-20RT and M/COOT | -- |

| Long Range Recon | Tu-22MR/BACKFIRE | Tu-95MR/BEAR-E | Tu-95MR/BEAR-E | IL-20M/COOT |

| Long Range EW | Tu-22MP/BACKFIRE | Tu-95KM/BEAR-C | Tu-95KM/BEAR-C | -- |

| Air Defense | ||||

| Operational-Strategic Systems | ||||

| Long-Range SAM/ABM | Triumf/SA-21, SA-24 | SA-20a w/SA-18 | SA-5b w/SA-16 | SA-5a w/S-60 |

| LR Tracked SAM/ABM | Antey-2500, SA-24 | SA-12a/SA-12b | SA-12a/SA-12b | SA-4b w/S-60 |

| LR Wheeled SAM/ABM | Favorit/SA-20b, SA-24 | SA-20a w/SA-18 | SA-10c w/SA-16 | SA-5a w/S-60 |

| Mobile Tracked SAM | Buk-M1-2 (SA-11 FO) | Buk-M1-2(SA-11 FO) | SA-6b w/ZSU-23-4 | SA-6a w/ZSU-23-4 |

| Towed Gun/Missile System | Skyguard III/Aspide2000 | Skyguard II/Aspide2000 | SA-3, S-60 w/radar | SA-3, S-60 w/radar |

| Tactical Short-Range Systems | ||||

| SR Tracked System (Div) | Pantsir S-1-0 | SA-15b w/SA-18 | SA-6b w/Gepard B2L | SA-6a w/ZSU-23-4 |

| SR Wheeled System (Div) | Crotale-NG w/SA-24 | FM-90 w/SA-18 | SA-8b w/ZSU-23-4 | SA-8a w/ZSU-23-4 |

| SR Gun/Missile System (Bde) | 2S6M1 | 2S6M1 | SA-13b w/ZSU-23-4 | SA-9 w/ZSU-23-4 |

| Man-portable SAM Launcher | SA-24 (Igla-S) | SA-24 (Igla-S) | SA-16 | SA-14, SA-7b |

| Airborne/Amphibious AA Gun | BTR-ZD Imp (w/-23M1) | BTR-ZD with ZU-23M | BTR-ZD/SA-16 | BTR-D/SA-16, ZPU-4 |

| Air Defense/Antitank | ||||

| Inf ADAT Vehicle-IFV | BMP-2M Berezhok/SA-24 | BMP-2M w/SA-24 | AMX-10 w/SA-16 | VTT-323 w/SA-14 |

| Inf ADAT Vehicle-APC | BTR-3E1/AT-5B/SA-24 | BTR-80A w/SA-24 | WZ-551 w/SA-16 | BTR-60PB w/SA-14 |

| ADAT Missile/Rocket Lchr | Starstreak II | Starstreak | C-5K | RPG-7V |

| Air Defense ATGM | 9P157-2/AT-15 and AD missile | 9P149/Ataka and AD missile | 9P149/AT-6 | 9P148/AT |

| Anti-Aircraft Guns | ||||

| Medium-Heavy Towed Gun | Skyguard III | S-60 with radar/1L15-1 | S-60 with radar/1L15-1 | KS-19 |

| Medium Towed Gun | Skyguard III | GDF-005 in Skyguard II | GDF-003/Skyguard | Type 65 |

| Light Towed Gun | ZU-23-2M1/SA-24 | ZU-23-2M | ZU-23 | ZPU-4 |

| Anti-Helicopter Mine | Temp-20 | Helkir | MON-200 | MON-100 |

| AD Spt (C2/Recon/EW) | ||||

| EW/TA Radar Strategic | Protivnik-GE and 96L6E | 64N6E and 96L6E | TALL KING-C | SPOON REST |

| EW/TA Rdr Anti-stealth | Nebo-SVU | Nebo-SVU | Nebo-SV | BOX SPRING |

| EW/TA Radar Op/Tac | Kasta-2E2/Giraffe-AMB | Kasta-2E2/Giraffe AMB | Giraffe 50 | LONG TRACK |

| Radar/C2 for SHORAD | Sborka PPRU-M1 | Sborka-M1/ PPRU-M1 | PPRU-1 (DOG EAR) | PU-12 |

| ELINT System | Orion/85V6E | Orion/85V6E | Tamara | Romona |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles | ||||

| High Altitude Long Range | Hermes 900 | Hermes 900 | Tu-143 | Tu-141 |

| Med Altitude Long Range | ASN-207 | ASN-207 / Hermes 450 | -- | -- |

| Tactical | Skylark II | Skylark II | Fox AT2 | ASN-104 |

| Vertical Take Off/ Landing | Camcopter S-100 | Camcopter S-100 | -- | -- |

| Vehicle/Man-Portable | Skylite-B | Skylite-A | -- | -- |

| Man-Portable | Skylark-IV | Skylark | -- | -- |

| Hand-Launch | Zala 421-12 | Zala 421-08 | Pustelga | -- |

| Artillery Launch | R-90 rocket | R-90 rocket | ||

| Attack UAVs/UCAVs | Hermes 450 | Hermes 450 | Mirach-150 | -- |

| Theater Missiles | ||||

| Medium Range (MRBM) | Shahab-3B | Shahab-3A | Nodong-1 | SS-1C/SCUD-B |

| Short-Range (SRBM) | SS-26 Iskander-M | SS-26 Iskander-E | M-9 | SS-1C/SCUD-B |

| SRBM/Hvy Rkt < 300 km | Lynx w/EXTRA missile | Tochka-U/SS-21 Mod 3 | M-7/CSS-8 | FROG-7 |

| Cruise Missile | Delilah ground, air, sea | Harpy programmed/piloted | Mirach-150 programmed | -- |

| Anti-ship CM | BrahMos ground, air, sea | Harpy programmed/radar | Exocet | Styx |

| Anti-radiation | Harpy programmed/ARM | Harpy programmed/ARM | -- | -- |

Appendix D: Road to War

BASELINE TO WAR

INTRODUCTION

The DATE Road to War (RTW) is intended to serve as a common starting point for all Army CTCs and TRADOC Schools and Centers to draw upon in formulating their scenarios and other supporting documentation for training events and exercises. This RTW is not the only possible narrative to assist in the generation of scenarios. Each CTC has the flexibility and freedom to adapt, change, or modify this RTW to fit the specific needs of each training event.

ROAD TO WAR REGIONAL CONDITIONS

US operations in the Caucasus occur in an increasingly hostile area of operations (AO). The current situation involves a broad political alliance of Ariana and Donovia to redraw the geopolitical map of the Caucasus to the exclusion of Western powers, and the functional end of currently independent states such as Gorgas and Atropia. The continuing competition by both Ariana and Donovia with Atropia in the international oil and gas markets, the latent ethnic tensions within Atropia, and other regional flashpoints continue to defy permanent diplomatic solutions. Should deterrence fail, US-led coalition forces may need to defeat aggressor nations militarily to support critical national and regional security objectives.

Politically, Ariana and Donovia broadly support each other’s specific Caucasian regional interests, despite differences in social and religious makeup. While the majority of both nations practice Islam, Ariana has a dominant Persian culture while Donovia is primarily Arabic. Both Ariana and Donovia view the existence of the hydrocarbon-rich Atropia as an outpost of the “colonialist West,” and both covet control of Atropia’s natural resources. Economically, Atropia serves as one of the largest oil and gas producers in the world, with much of its hydrocarbon products used by Western countries. Atropian independence in setting its own gas/oil prices and policies has angered Ariana, who is also upset by the political independence that such oil and gas production and its accompanying hard currency income gives Atropia. Atropia also has a largely secular government (though not, strictly speaking, a democratic one). All things considered, Atropia is generally a less repressive state than its Arianian neighbor, although Ariana likes to claim that Atropia is quite repressive.

Atropia’s neighbor and historical enemy, Limaria, typically attempts to remain neutral in the growing regional tension. While broadly aligned with Donovia despite their religious differences, Limaria continually maneuvers to stay clear of the fight between Atropia and its neighbors. Unlike Atropia, Limaria does not export hydrocarbons but desires to become involved in the hydrocarbon export business, primarily through new pipelines. Limaria enjoys an unspoken but enduring security and economic relationship with Donovia, and a frosty relationship—punctuated by violence and ethnic tension—with Atropia.

Atropia remains determined to maintain its independence and ensure the safe export of its hydrocarbon resources, primarily through pipelines traversing its neighbor, Gorgas. Both Atropia and Gorgas continue, with varying levels of success, to placate or balance the demands of Donovia and Ariana, while Atropia and Gorgas vigorously court European and US diplomatic support; possible inclusion in NATO; and, specifically, US security guarantees. The Atropians attempt to balance these diplomatic links to the West in a way that is less likely to inflame regional tensions, feed Arianian or Donovian perception management operations, or give either Ariana or Donovia a causus belli to attack Atropia.

The Gorgans, on the other hand, willingly welcome US Government involvement in their country, including diplomatic and military “advisory groups” to build Gorgan military capability and interoperability with NATO forces. Gorgas has a frosty relationship with Donovia, and cooperation built on mutual need with Atropia. Ultimately, Gorgas remains Atropia’s best outlet for its resources, and this relationship with Atropia gives Gorgas geopolitical value to the West.

In addition to an unstable diplomatic situation, a variety of terrorist groups and other non-state actors are operating within the AO, some with state backing, and others pursuing religious and ethnic goals. Criminality in the form of significant trafficking in illicit goods, along with other organized crime, is endemic to the region.

ROAD TO WAR EVENTS

Over the last 24 months, undeniable intelligence shows a slow but steady redeployment of Arianian ground combat power, both in conventional and unconventional forces, to the Caucasus, primarily along Ariana’s northern border shared with Atropia. Despite Arianian claims of a defensive build-up designed to protect Arianian interests from Western attack, other intelligence indicates Arianian hostile intent toward Atropia. Arianian military and government assets—including oil survey and coastal defense ships, civil and military aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles, and other military assets—continue to actively and aggressively reconnoiter Atropian hydrocarbon and defense interests. Ariana has also moved its air and missile strike assets into range of Atropia. Additionally, Arianian-based INFOWAR capabilities have been probing Atropian government networks (including those for oil/gas production) and using the Internet, including social media, to carry out an aggressive perception management operation against the Atropian population. Much of this content focuses on the repressive nature of the Atropian government and its close links to the US. The Arianian military has also made preparations for the mass expulsion of ethnic Atropians from the north of Ariana as well as preparations for advance northward.

Politically, the Arianians view Atropia’s Western orientation as part of an encirclement of Ariana by the West and nations viewed as Western proxies. The Arianians also fear secularized and independent Atropia’s growing power to encourage ethnic Atropians within Ariana to join their ethnic homeland. Over the last two years, Arianian political and religious figures have described the Atropian government in progressively more hostile terms. Combined with increasing military maneuvers and other display-of-force actions, the tone between Atropia and Ariana has chilled considerably. In perception management operations over the last 12 months, Arianians have portrayed the large Atropian minority population within Ariana as well-treated and integrated, as compared to the majority of Atropians within Atropia, whom the Arianian government claims are exploited by the Atropian ruling family. Additionally¸ the Arianians have claimed in revised textbooks and official maps that Atropia is an “historical part” of Ariana. The Atropian government has attempted to diplomatically extinguish such rhetoric, while quietly beginning preparations for potential conflict with Ariana.

Within the last year, the US President issued a Presidential National Security Directive (PNSD) that identifies respect for current Caucasus international boundaries and continued unfettered export of Caucasus oil and gas supplies as vital US national security interests. The PNSD also directed the Department of Defense to create and deploy a Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) to the Caucasus to demonstrate US resolve and deter potential aggression. Should shaping and deterrence fail, the CJTF must be prepared to conduct decisive operations.

The US has publicly responded to growing Arianian propaganda by demanding respect for all Caucasus state boundaries. The US approached multilateral organizations, but few other countries seem willing to risk the backlash of an Arianian-sponsored oil embargo. In the last six months, border skirmishes between Arianian and Atropian border guards, overflight of Atropian terrain by Arianian air assets, and official Arianian naval vessel incursions into the Caspian Sea—home of the bulk of Atropian oil and gas fields—have increased. Six weeks ago, an Arianian military patrol “strayed” 10 kilometers into Atropian territory before being chased back into Ariana.

Last week, Atropia responded by mobilizing a portion of its Reserves to increase its border security. Citing an “imminent attack,” Ariana initiated artillery fire and air strikes on Atropian military structures, though clearly sparing oil fields and production facilities. Ariana then demanded that Atropia “demilitarize” its border with Ariana and stop all oil exports. Ariana also demanded a “free and fair election” in Atropia, to be administered by Arianian-affiliated organizations. Ariana threatened the world community, and specifically the US, against intervention. Ariana warned of dire consequences if the West—most clearly the US—threatened the “political development of Atropia with aggressive military action to prop up an anti-Islamic puppet state.” Atropia refused to accede to the Arianian demands. The day after Atropia’s refusal, Arianian forces commenced a conventional assault on Atropia, and the US announced deployment of combat forces within the CJTF to roll back Arianian aggression.