Chapter 2: Hybrid Threat Force Structure

- This page is a section of TC 7-100.4 Hybrid Threat Force Structure Organization Guide.

This chapter and the organizational directories to which it is linked provide the Hybrid Threat Force Structure (HTFS) to be used as the basis for a threat organization in all Army training, except real-world-oriented mission rehearsal exercises. This includes the forces of Threat actors as well as key non-state actors. In most cases, the organizations found in the HTFS will require task-organizing (see chapter 3) in order to construct a threat order of battle appropriate for a training event. Refer to the Hybrid Threat Force Structure Organization Guide for an overview of all the chapters.

Contents

- 1 Section I - Threat Forces: Strategic Level

- 2 Section II - Threat Forces: Operational Level

- 3 Section III - Threat Forces: Tactical Level

- 4 Section IV - Irregular Forces

- 5 Section V - Organizational Directories

Section I - Threat Forces: Strategic Level

When the Hybrid Threat consists of or includes the regular and/or irregular forces of a Threat, the national-level structure of that state, including the overall military and paramilitary structure, should follow the patterns described in TC 7-100 Hybrid Threat. Those patterns are summarized here. (See TC 7-100 for more detail.)

The 7-100 series refers to the country in question as “the State.” In specific U.S. Army training environments, however, the generic name of the State may give way to other fictitious country names used in the specific training scenarios for example the countries listed in the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE). (See AR 350-2 for additional guidance concerning the use of country names in a scenario.) The State possesses various military and paramilitary forces as well as irregular forces with which to pursue its national interests. This section of chapter 2 describes the national-level command structure and the various services that control these forces. For more information on the Decisive Action Training Environment go to the ATN Website at: https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=311 and click on the Decisive Action Training Environment.

The State’s Armed Forces have a threat force structure (TFS) that manages military forces in peacetime. This TFS is the aggregate of various military headquarters, organizations, facilities, and installations designed to man, train, and equip the forces. Within the TFS, tactical-level commands have standard organizational structures (as depicted in the organizational directories). However, these TFS organizations normally differ from the Threat’s wartime fighting force structure. (See chapter 3 on Task- Organizing.)

The TFS includes all components of the Armed Forces—not only regular, standing forces (active component), but also reserve and militia forces (reserve component). Certain elements of the Threat Force Structure will also coordinate an affiliation with irregular forces if the scenario requires this relationship. For more information see table 3-1 Command and Support Relationships. For administrative purposes, both regular and reserve forces come under the headquarters of their respective service component. Each of the six service components is responsible for manning, equipping, and training of its forces and for organizing them within the TFS.

National-level Command Structure

The State employs its military forces, along with its other instruments of power, to pursue its tactical, operational, and strategic goals and, thus, support its national security strategy. The national-level command structure includes the National Command Authority, the Ministry of Defense, and the General Staff. (See figure 2-1 on page 2-2.)

National Command Authority

The National Command Authority (NCA) exercises overall control of the application of all instruments of national power in planning and carrying out the national security strategy. The NCA allocates forces and establishes general plans for the conduct of national strategic campaigns. The NCA exercises control over the makeup and actions of the Armed Forces through the Ministry of Defense and the General Staff.

Ministry of Defense

The Ministry of Defense (MOD) is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the Armed Forces and for the readiness and overall development of the six service components of the Armed Forces. However, the General Staff has direct control over the six services. In wartime, the MOD merges with the General Staff to form the Supreme High Command (SHC). The countries in the Decisive Action Training Environment use the SHC to show this structure.

General Staff

The General Staff is a major link in the centralization of military command at the national level, since it provides staff support and acts as the executive agency for the NCA. Together with the MOD, the General Staff forms the SHC in wartime. The General Staff has direct control over the six services, and all military forces report through it to the NCA. The Chief of the General Staff commands the SHC.

Service Components

The Armed Forces generally consist of six services. These include the Army, Navy, Air Force (which includes the national-level Air Defense Forces), Strategic Forces (with long-range rockets and missiles), Special-Purpose Forces (SPF) Command, and Internal Security Forces. The Internal Security Forces are subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime, but become subordinate to the SHC in time of war.

The Armed Forces field some reserve component forces in all services, but most reserve forces are Army forces. Militia forces belong exclusively to the ground component.

Note. Regular, reserve, and militia forces of the State can maintain various relationships with insurgent, guerrilla, and possibly criminal organizations.

Army

The Army includes tank, mechanized infantry, motorized infantry, and a small number of airborne and special-purpose forces (Army SPF). The Army fields both rocket and tube artillery to support ground operations. The Army also has some long-range rockets and surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs). Fire support capability includes attack helicopters of Army aviation. The Army is assigned large numbers of shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and will also have mobile air defense units in support.

The State maintains a regional force-projection navy with a significant access-control capability built on small surface combatants, submarines, surface- and ground-based antiship missile units, and antiship mines. The Navy has a limited amphibious capability and possesses naval infantry capable of conducting forcible entry against regional opponents. The Navy also fields organic Special-Purpose Forces (Naval SPF).

Note. If the State in a particular scenario is a landlocked country, it may not have a navy.

Air Force

The Air Force, like the Navy, is fundamentally a supporting arm. Its aircraft include fighters, bombers, tactical transport, tankers, airborne early warning aircraft, electronic warfare (EW) aircraft, reconnaissance aircraft, and auxiliaries. The State’s national-level Air Defense Forces are subordinate to the Air Force. Similar to other services, the Air Force has its own organic Air Force SPF.

Strategic Forces

The Strategic Forces consist of long-range rocket and missile units. The missiles of the Strategic Forces are capable of delivering chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) munitions, and the NCA is the ultimate CBRN release authority. The State considers the Strategic Forces capability, even when delivering conventional munitions, the responsibility of the NCA. Therefore, the NCA is likely to retain major elements of the Strategic Forces under its direct control or under the SHC or a theater headquarters in wartime. In some cases, the SHC or theater commander may allocate some Strategic Forces assets down to operational-level commands. Conventionally-armed rocket, INFOWAR, and missile units may be assigned directly in support of air, naval, and ground forces.

Special-purpose Forces Command

The SPF Command includes both SPF units and elite commando units. The General Staff or SHC normally reserves some of these units under its own control for strategic-level missions. It may allocate some SPF units to subordinate operational or theater commands, but can still task the allocated units to support strategic missions, if required.

Four of the five other service components also have their own SPF. In contrast to the units of the SPF Command, the Army, Navy, and Air Force SPF are designed for use at the operational level. The Internal Security Forces also have their own SPF units. These service SPF normally remain under the control of their respective services or a joint operational or theater command. However, SPF from any of these service components could become part of joint SPF operations in support of national-level requirements. The SPF Command has the means to control joint SPF operations as required.

Any SPF units (from the SPF Command or from other service components’ SPF) that have reconnaissance or direct action missions supporting strategic-level objectives or intelligence requirements would normally be under the direct control of the SHC or under the control of the SPF Command, which reports directly to the SHC. Also, any service SPF units assigned to joint SPF operations would temporarily come under the control of the SPF Command or perhaps the SHC.

Most of the service SPF units are intended for use at the operational level. Thus, they can be subordinate to operational-level commands even in the TFS. In peacetime and in garrisons within the State, SPF of both the SPF Command and other services are organized administratively into SPF companies, battalions and brigades.

Note. SPF can organize, train, and support local irregular forces (insurgents or guerrillas and possibly even criminal organizations) and conduct operations in conjunction with them. SPF missions can also include the use of terror tactics.

Internal Security Forces

Internal security forces are designed to deal with various internal threats to the regime. In peacetime, the Chief of Internal Security heads the forces within the Ministry of the Interior that fall under the general label of “internal security forces.” (See figure 2-2.) Most of the internal security forces are uniformed, using military ranks and insignia similar to those of the other services of the State’s Armed Forces.

During wartime, some or all of the internal security forces from the Ministry of the Interior become subordinate to the SHC. Thus, they become the sixth service component of the Armed Forces. At that time, the formal name “Internal Security Forces” applies to all forces resubordinated from the Ministry of the Interior to the SHC, and the General Staff controls and supervises their activities. The forces resubordinated to the SHC are most likely to come from the Security Directorate, the General Police Directorate, or the Civil Defense Directorate.Security Directorate

The Security Directorate has elements deployed throughout the state. Many of these elements are paramilitary units equipped for combat. They include Border Guard Forces, National Security Forces, and Special-Purpose Forces. Together with the regular Armed Forces, these paramilitary forces help maintain the state's control over its population in peace and war.

The Border Guard Forces consist of a professional cadre of officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) supplemented by conscripts and civilian auxiliaries. During war, they may be assigned to a military unit to guard a newly gained territory or to conduct actions against the enemy. The Border Guard Forces may also have one or more independent special border battalions. These constitute an elite paramilitary force of airborne-qualified personnel trained in counterterrorism and commando tactics. When the SHC assumes control of Border Guard Forces in wartime, the General Staff provides overarching administrative and logistics support in the same manner as with a regular military force.

The National Security Forces are organized along military lines and equipped with light weapons and sometimes heavy weapons and armored vehicles. This organization conducts liaison with other internal security forces and with other services of the State’s Armed Forces and may combine with them to conduct certain actions. An operational-level command of the State’s Armed Forces may include one or more security brigades to augment its military capability. This type of brigade not only increases the military combat power, but also offers a very effective and experienced force for controlling the local population. Security battalions, companies, and platoons are similar to equivalent infantry units in the regular Armed Forces and can thus be used to augment such forces.

Within the Security Directorate, the Ministry of the Interior has its own Special-Purpose Forces (SPF). These are the most highly-trained and best-equipped of the internal security forces. The State Security Directorate maintains its SPF units as a strategic reserve for emergency use in any part of the State or even outside State borders. The commando-type SPF forces can conduct covert missions in support of other internal security forces or regular military forces. SPF activities may include the formation and training of an insurgent force in a neighboring country. In wartime, the SHC may use them to secure occupied territory or to operate as combat troops in conjunction with other services of the Armed Forces.

General Police Directorate

The General Police Directorate has responsibility for national, district, and local police. In some circumstances, police forces at all three levels operate as paramilitary forces. They can use military-type tactics, weapons, and equipment. National Police forces include paramilitary tactical units that are equipped for combat, if necessary. These uniformed forces may represent the equivalent of an infantry organization in the regular Armed Forces. Within the various national- and district-level police organizations, the special police are the forces that most resemble regular armed forces in their organization, equipment, training, and missions. Because some special police units are equipped with heavy weapons and armored vehicles, they can provide combat potential to conduct defensive operations if required. Thus, special police units could be expected to supplement the Armed Forces in a crisis situation.

Civil Defense Directorate

The Civil Defense Directorate comprises a variety of paramilitary and nonmilitary units. While the majority of Civil Defense personnel are civilians, members of paramilitary units and some staff elements at the national and district levels hold military ranks. Civil Defense paramilitary units are responsible for the protection and defense of the area or installation where they are located. Even the nonmilitary, civil engineering units can supplement the combat engineers of the Armed Forces by conducting engineer reconnaissance, conducting explosive ordnance disposal, and providing force-protection construction support and logistics enhancements required to sustain military operations.

Reserves and Militia

Although all six services can field some reserve forces, most of the reserve forces are Army forces. All militia forces belong to the Army component. Overall planning for mobilization of reserves and militia is the responsibility of the Organization and Mobilization Directorate of the General Staff. Each service component headquarters would have a similar directorate responsible for mobilization of forces within that service. Major geographical commands (and other administrative commands at the operational level and higher) serve as a framework for mobilization of reserve and militia forces.

Note. The Army is normally the dominant partner among the services, but relies on the mobilization of reserve and militia forces to conduct sustained operations. These additional forces are not as well-trained and -equipped as the standing Army. Militia forces are composed primarily of infantry and can act in concert with regular forces.

During mobilization, some reserve personnel serve as individual replacements for combat losses in active units, and some fill positions (including professional and technical specialists) that were left vacant in peacetime in deference to requirements of the civilian sector. However, reservists also man reserve units that are mobilized as units to replace other units that have become combat-ineffective or to provide additional units necessary for large, sustained operations.

Like active force units, most mobilized reserve and militia units do not necessarily go to war under the same administrative headquarters that controlled them in peacetime. Rather, they typically become part of a task-organized operational- or tactical-level fighting command tailored for a particular mission. In most cases, the mobilized reserve units would be integrated with regular military units in such a fighting command. In rare cases, however, a reserve command at division level or higher might become a fighting command or serve as the basis for forming a fighting command based partially or entirely on reserve forces.

Theater Headquarters

For the Threat, a theater is a clearly defined geographic area in which the Threat’s Armed Forces plan to conduct or are conducting military operations. Within its region, the Threat may plan or conduct a strategic campaign in a single theater or in multiple theaters, depending on the situation. The General Staff may create one or more separate theater headquarters even in peacetime, for planning purposes. However, no forces would be subordinated to such a headquarters until the activation of a particular strategic campaign plan.

Note. The term theater may have a different meaning for the State than for a major extraregional power, such as the United States. For an extraregional power with global force-projection capability, a theater is any one of several geographic areas of the world where its forces may become involved. For the State, however, the only theater (or theaters) in question would be within the region of the world in which the State is located and is capable of exerting its regionally-centered power. The extraregional power may not define the limits of this specific region in exactly the same way that the State defines it, in terms of its own perceptions and interests. Within its region, the State may plan or conduct a strategic campaign in a single theater or in multiple theaters, depending on the situation.

A theater headquarters provides flexible and responsive control of all theater forces. When there is only one theater, as is typical, the theater headquarters may also be the field headquarters of the SHC, and the Chief of the General Staff may also be the theater commander. Even in this case, however, the Chief of the General Staff may choose to focus his attention on national strategic matters and to create a separate theater headquarters, commanded by another general officer, to control operations within the theater.

When parts of the strategic campaign take place in separated geographical areas and there is more than one major line of operations, the State may employ more than one theater headquarters, each of which could have its own theater campaign plan. In this case, albeit rare, the SHC field headquarters would be a separate entity exercising control over the multiple theater headquarters.

The existence of one or more separate theater headquarters could enable the SHC to focus on the strategic campaign and sustaining the forces in the field. A theater headquarters acts to effectively centralize and integrate General Staff control over theater-wide operations. The chief responsibility of this headquarters is to exercise command over all forces assigned to a theater in accordance with mission and aim assigned by the SHC. A theater headquarters links the operational efforts of the OPFOR to the strategic efforts and reports directly to the SHC.

If the General Staff or SHC elects to create more than one theater headquarters, it may allocate parts of the TFS to each of the theaters, normally along geographic lines. One example would be to divide Air Force assets into theater air armies. Another would be to assign units from the SPF Command to each theater, according to theater requirements. During peacetime, however, a separate theater headquarters typically would exist for planning purposes only and would not have any forces actually subordinated to it.

Section II - Threat Forces: Operational Level

The organizational directories do not show organization charts or equipment lists for operational- level commands. That is because there are no standard organizations above division level in the TFS. However, the directories do provide the organizational building blocks for constructing operational-level commands appropriate to a given training scenario.In peacetime, each service commonly maintains its forces grouped under single-service operational- level commands (such as corps, armies, or army groups) for administrative purposes. In some cases, forces may be grouped administratively under operational-level geographical commands designated as military regions or military districts (see note). There are no standard “table of organization and equipment (TOE)” organizations for these echelons above division. For example, an army group can consist of several armies, corps, or separate divisions and brigades. In peacetime, the internal security forces are under the administrative control of the Ministry of the Interior. (See figure 2-3.) Normally, these administrative groupings differ from the Armed Forces’ go-to-war (fighting) force structure (see chapter 3).

Note. A military district may or may not coincide with a political district within the State government.

In wartime, most major administrative commands continue to exist under their respective service headquarters. However, their normal role is to serve as force providers during the creation of operational- level fighting commands. Operational-level commands of the TFS generally remain in garrison and continue to exercise command and control (C2) and administrative supervision of any of their original subordinates (or portions thereof) that do not become part of the fighting force structure. See chapter 3 for more information on the formation of wartime fighting commands.

Section III - Threat Forces: Tactical Level

In the HTFS, the largest tactical-level organizations are divisions and brigades. In peacetime, they are often subordinate to a larger, operational-level administrative command. However, a service of the Armed Forces might also maintain some separate single-service tactical-level commands (divisions, brigades, or battalions) directly under the control of their service headquarters. (See figure 2-3 on page 2-7.) For example, major tactical-level commands of the Air Force, Navy, Strategic Forces, and the SPF Command often remain under the direct control of their respective service component headquarters. The Army component headquarters may retain centralized control of certain elite elements of the ground forces, including airborne units and Army SPF. This permits flexibility in the employment of these relatively scarce assets in response to national-level requirements.

For these tactical-level organizations (division and below), the HTFS organizational directories contain standard “TOE” structures. However, these administrative groupings normally differ from the Threat’s go-to-war (fighting) force structure. (See chapter 3 on Task-Organizing.)

Divisions

In the Threat’s HTFS, the largest tactical formation is the division. Divisions are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a division tactical group (DTG), if necessary. (See chapter 3.) However, a division, with or without becoming a DTG, could fight as part of an operational-strategic command (OSC) or an organization in the HTFS (such as army or military region) or as a separate unit in a field group (FG).

Maneuver Brigades

The OPFOR’s basic combined arms unit is the maneuver brigade. In the HTFS, some maneuver brigades are constituent to divisions, in which case the OPFOR refers to them as divisional brigades. However, some are organized as separate brigades, designed to have greater ability to accomplish independent missions without further allocation of forces from a higher tactical-level headquarters. Separate brigades have some subordinate units that are the same as in a divisional brigade of the same type (for example, the headquarters), some that are especially tailored to the needs of a separate brigade [marked “(Sep”) in the organizational directories], and some that are the same as units of this type found at division level [marked “(Div)”].

Maneuver brigades are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a brigade tactical group (BTG), if necessary. However, a brigade, with or without becoming a BTG, can fight as part of a division or DTG, or as a separate unit in an OSC, an organization of the HTFS (such as army, corps, or military district), or an FG.

Battalions

In the HTFS, the basic unit of action is the battalion. Battalions are designed to be able to execute basic combat missions as part of a larger tactical force. A battalion most frequently would fight as part of a brigade, BTG, or DTG. A battalion can also serve as the basis for forming a battalion-size detachment (BDET), if necessary. (See chapter 3.)

Companies

Threat companies most frequently fight as part of a battalion or BTG. However, companies are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a company-size detachment (CDET), if necessary. (See chapter 3.)

Platoons

In the threat force structure, the smallest unit typically expected to conduct independent fire and maneuver tactical tasks is the platoon. Platoons are designed to be able to serve as the basis for forming a reconnaissance or fighting patrol. A platoon typically fights as part of a company, battalion, or detachment.

Aviatoin Units

The threat has a variety of attack, transport, multipurpose, and special-purpose helicopters that belong to the ground forces (Army) rather than the Air Force. Hence the term army aviation. Army aviation units follow the organizational pattern of other ground forces units, and are thus organized into brigades, battalions, and companies.

Air Force organizations are grouped on a functional, mission-related basis into divisions, regiments, squadrons, and flights. For example, a bomber division is composed primarily of bomber regiments, and a fighter regiment is composed mainly of fighter squadrons. The Air Force also has some mixed aviation units with a combination of fixed- and rotary-wing assets; these follow the normal Air Force organizational pattern, with mixed aviation regiments and squadrons. However, rotary-wing subordinates of these mixed aviation units would be battalions and companies (rather than squadrons and flights), following the pattern of similar units in army aviation. Various fixed- and/or rotary-wing Air Force assets may be task-organized as part of a joint, operational-level command in wartime.

Nondivisional Units

Units listed as "nondivisional" [marked “(Nondiv”)] in the HTFS organizational directories might be found in any of the operational-level commands discussed above, or in a theater command, or directly subordinate to the appropriate service headquarters. The HTFS contains brigade- and battalion-size units of single arms such as SAM, artillery, SSM, antitank, combat helicopter, signal, and INFOWAR. In wartime, these nondivisional units can become part of a task-organized operational- or tactical-level command. These units almost always operate in support of a larger formation and only rarely as tactical groups or detachments, or on independent missions.

Section IV - Irregular Forces

Irregular forces are armed individuals or groups who are not members of the regular armed forces, police, or other internal security forces (JP 3-24). The OPFOR recognizes how its adversaries and enemies categorize irregular forces. The distinction of being armed as an individual or group can include a wide range of people who can be categorized correctly or incorrectly as irregular forces. Excluding members of regular armed forces, police, or internal security forces from being considered irregular forces may appear to add some clarity. However, such exclusion is inappropriate when a soldier of a regular armed force, policeman, or internal security force member is concurrently operating in support of insurgent, guerrilla, or criminal activities. (See TC 7-100.3 for a detailed discussion of irregular opposing forces.)

Irregular forces can be insurgent, guerrilla, or criminal organizations or any combination that might also include armed and unarmed combatants. Any of these OPFOR individuals, groups, organizations, units, or forces can be affiliated with mercenaries, corrupt governing authority officials, compromised commercial and public entities, active or covert supporters, and willing or coerced members of a populace. Independent OPFOR actors can also act on agendas separate from those of irregular forces but be categorized as an irregular element. An additional complication is determining who is or may be an armed combatant and/or unarmed combatant, and what is or may be a legitimate or an illicit commercial or private organization.

Terrorism is a tactic often associated with irregular forces. Acts of terrorism demonstrate an intention to cause significant psychological and/or physical effects on a relevant population through the use or threat of violence. Terrorism strategies are typically a long-term commitment to degrade the resilience of an enemy in order to obtain concessions from an enemy with whom terrorists are in conflict. International conventions and/or law of war protocols on armed conflict are often not a constraint on terrorists. Whether acts of terrorism are deliberate, apparently random, and/or purposely haphazard, the physical, symbolic, and/or psychological effects can diminish the confidence of a relevant population for its key leaders and governing institutions. The OPFOR uses terrorism when these tactics achieve actions or reactions of an enemy and/or relevant population that benefit the OPFOR operational or strategic objectives.

Irregular Organizations

Irregular organizations are distinct from the regular armed forces of a sovereign nation state, but can resemble them in organization, equipment, training, or mission. Therefore, the HTFS organizational directories include baseline organizations for insurgent and guerrilla forces (see examples in appendixes C and E), as well as criminal organizations and private security organizations. This TC presents OPFOR organizational considerations for training, professional education, and leader development venues as follows:

- Insurgent organization

- Guerrilla unit

- Criminal organizations

- Noncombatants—when this category of individual is complicit in activities as coerced or willing members of irregular forces. Notwithstanding, many noncombatants conduct legitimate private or commercial activities that complicate identifying noncombatant supporters of irregular forces.

Irregular forces may operate in other than military or military-like (paramilitary) capacities and present diverse threats in an OE. “A threat is any combination of actors, entities, or forces that have the capability and intent to harm U.S. forces, U.S. national interests, or the homeland. Threats may include individuals, groups of individuals (organized or not organized), paramilitary or military forces, nation- states, or national alliances. When threats execute their capability to do harm to the United States, they become enemies” (ADRP 3-0). Irregular forces can also be part of a hybrid threat, that is, “the diverse and dynamic combination of regular forces, irregular forces, terrorist forces, and/or criminal elements unified to achieve mutually benefitting effects” (ADRP 3-0). A hybrid threat can consist of any combination of two or more of these components. ADRP 3-0 defines an enemy as “a party identified as hostile against which the use of force is authorized.” The OPFOR apply these definitions in its organization and irregular force operations.

Insurgent Organizations

Insurgent organizations have no regular, fixed table of organization and equipment structure. The mission, environment, geographic factors, and other OE variables determine the configuration and composition of each insurgent organization and its subordinate cells. Their composition varies from organization to organization, mission to mission, and environment to environment. Insurgent organizations are typically composed of from three to over 30 cells. All of the direct action cells could be multifunction (or multipurpose), or some may have a more specialized focus. The single focus may be a multifunction direct action mission, assassination, sniper, ambush, kidnapping, extortion, hijacking and hostage taking, or mortar and rocket attacks. Each of these may be the focus of one or more cells. More often, the direct action cells are composed of a mix of these capabilities and several multifunction cells. There are also a number of types of supporting cells with various functions that provide support to the direct action cells or to the insurgent organization as a whole. Thus, a particular insurgent organization could be composed of varying numbers of multifunction or specialty direct action cells, supporting cells, or any mix of cells. (See TC 7-100.3.)

Insurgents are armed and/or unarmed individuals or groups who promote an agenda of subversion and violence that seek to overthrow or force change of a governing authority. They can transition between subversion and violence dependent on specific conditions to organize use of subversion and violence to seize, nullify, or challenge political control of a region. The intention is to gradually undermine the confidence of a relevant population in a governing authority’s ability to provide and justly administer civil law, order, and stability.

Several factors differentiate the structure and capabilities of an insurgent organization (direct action cells and support cells) from the structure and capabilities of a guerrilla unit. An insurgent organization can be primarily a covert organization with a cellular structure to minimize possible compromise of the overall organization. Much of the organizational structure may be disguised within a relevant population. By comparison, a guerrilla unit displays military-like unit structure, systems, member appearance, and leadership titles. Insurgent organizations typically do not have many of the heavier weapon systems and more sophisticated equipment that guerrilla units can possess. The weapons of the insurgents are generally limited to small arms, antitank grenade launchers, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and may possess limited crew-served weapons (82-mm mortar, 107-mm single-tube rocket launcher). In the event the insurgents require heavier weapons or capabilities, they might obtain them from guerrillas or the guerrilla unit might provide its services depending on a mutually supporting relationship between the two organizations.

Insurgent organizations normally conduct irregular conflict within or near the sovereign territory of a state in order to overthrow or force change in that state’s governing authority. Some insurgent activities— such as influencing public opinion and acquiring resources—can occur outside of the geographic area that is the focus of the insurgency.

An insurgent organization may originate and remain at the local level. A local insurgent organization may exist at small city, town, village, parish, community, or neighborhood level. It may expand and/or combine with other local organizations. Cities with a large population or covering a large area may be considered regions and may include several local insurgent organizations. A higher insurgent organization may exist at regional, provincial, district, national, or transnational level. The OE and the specific goals determine the size and composition of each insurgent organization and the scope of its activities.

Higher Insurgent Organizations

The higher insurgent organization includes any insurgent organization at regional, provincial, district, or national level, or at the transnational level. Cities with a large population or covering a large geographic area are considered regions. Higher insurgent organizations can have transnational affiliations or other overt and/or covert support. (See Tc 7-100.3.)

Higher insurgent organizations usually contain a mix of local insurgent organizations and guerrilla units. Each of these organizations provides differing capabilities. The main capabilities of a higher insurgent organization that are not usually present in a local insurgent organization are as follows:

- Subordinate local insurgent organizations in their network. (Local insurgent organizations usually do not have echeloned subordinate local insurgent organizations.)

- Guerrilla units within their network and operating in the same geographic area. (Local insurgent organizations may have temporary affiliations with guerrilla units or may occasionally command and control them.)

- Personal protection and security cell(s) for the organization’s senior leaders and designated advisors or special members. (A local insurgent organization does not normally have a personal protection and security cell.)

- Associations and/or affiliations with criminal organizations directly and without coordination with subordinate local insurgent organizations. (The long-term vision in a higher insurgent organization may include cooperation with regional or transnational criminal organizations for specific capabilities or materiel available through criminal networks.)

Local Insurgent Organizations

The term local insurgent organization applies to any insurgent organization below regional, provincial, or district level. This includes small cities, towns, villages, parishes, communities, neighborhoods, and/or rural environments. Large cities are equivalent to regions and may contain several local insurgent organizations. Activities remain focused on a local relevant population. (See TC 7-100.3.)

Local insurgent organizations may or may not be associated with or subordinate to a higher insurgent organization at the regional, national, or transnational level. The local insurgents may operate independently, without central guidance or direction from the overall movement, and may not be associated with a larger, higher insurgent movement in any manner. The local insurgent organization can be subordinate to, loosely affiliated with, or completely autonomous and independent of higher insurgent organizations. These relationships are generally fluctuating and may be mission dependent, agenda- oriented motivations.

Differences between a local insurgent organization and a higher insurgent organization are as follows:

- Direct actions cells are present within a local insurgent organization. Their multifunctional and/or specific functional capabilities may be enhanced or limited based on availability of resources and technical expertise in or transiting the local OE. These direct actions are planned for immediate and/or near-term effects related to the local insurgent organization’s area of influence.

- Guerrilla units might not be subordinate to the local insurgent organization. However, temporary affiliations between local insurgents and guerrillas are possible for specified missions coordinated by a higher insurgent organization. Direct action personnel may use, fight alongside of, or assist affiliated forces, and guerrillas to achieve their common goals or for any other agenda. Guerrilla units may operate in a local insurgent organization’s area of influence and have no connection to the local insurgent organization or a higher insurgent organization.

- Criminals can affiliate with a local insurgent organization or a higher insurgent organization as a matter of convenience and remain cooperative only as long as criminal organization aims are being achieved. The local insurgent organization retains a long-term vision of its political agenda, whereas cooperation by a criminal organization is usually related to local commercial profit and/or organizational influence in a local environment. This usually equates to criminals controlling or facilitating materiel and commodity exchanges. The criminal is not motivated by a political agenda.

Appendix C provides an example of a typical local insurgent organization, taken from volume III of the HTFS organizational directories. For illustrative purposes, this example includes a reasonable number of multifunction direct action cells (four) and at least one cell of each of the 18 other more specialized types. The dashed boxes in the organizational graphic indicate the possibilities for varying numbers of each type of cell, depending on the functions required for the insurgent organization to accomplish its mission. Insurgent organizations may a relationship with guerrilla organizations, criminal organizations, and/or other actors based on similar or shared goals and/or interests. The nature of the shared goal/interest determines the tenure and type of relationship and the degree of affiliation or association. Guerrilla Units

A guerrilla force is a group of irregular, predominantly indigenous personnel organized along military lines to conduct military and paramilitary operations in enemy-held, hostile, or denied territory (JP 3-05). Thus, guerrilla units are an irregular force, but structured similar to regular military forces. They resemble military forces in their command and control (C2) and can use military-like tactics and techniques. Guerrillas normally operate in areas occupied by an enemy or where a hostile actor threatens their intended purpose and objectives. Therefore, guerrilla units adapt to circumstances and available resources in order to sustain or improve their combat power. Guerrillas do not necessarily comply with international law or conventions on the conduct of armed conflict between and among declared belligerents.

Compared to insurgent organizations as a whole, guerrilla units have a more military-like structure. Within this structure, guerrillas can have some of the same types of weapons as a regular military force. The guerrilla unit contains weapons up to and including 120-mm mortars, antitank guided missiles (ATGMs), and man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS), and can conduct limited mine warfare and sapper attacks. Other examples of equipment and capability the guerrillas can have in their units that the insurgents generally do not have are 12.7-mm heavy machineguns; .50-cal anti-materiel rifles; 73-, 82-, and 84-mm recoilless guns; 100- and 120-mm mortars; 107-mm multiple rocket launchers; 122-mm rocket launchers; GPS jammers; and signals intelligence capabilities.

The area of operations (AOR) for guerrilla units may be quite large in relation to the size of the force. A large number of small guerrilla units can be widely dispersed. Guerrilla operations may also occur as independent squad or team actions. In other cases, operations could involve a guerrilla brigade and/or independent units at battalion, company, and platoon levels. A guerrilla unit can be an independent paramilitary organization and/or a military-like component of an insurgency. Guerrilla actions focus on the tactical level of conflict and its operational impacts. Guerrilla units can operate at various levels of local, regional, or international reach. In some cases, transnational affiliations can provide significant support to guerrilla operations.

Guerrilla units may be as large as several brigades or as small as a platoon and/or independent hunter/killer (H/K) teams. The structure of the organization depends on several factors including the physical environment, sociological demographics and relationships, economics, and support available from external organizations and/or countries. Some guerrilla units may constitute a paramilitary arm of an insurgent movement, while other units may pursue guerrilla warfare independently from or loosely affiliated with an insurgent organization.

Some guerrilla units may have honorific titles that do not reflect their true nature or size. For example, a guerrilla force that is actually of no more than battalion size may call itself a “brigade,” a “corps,” or an “army.” A guerrilla unit may also refer to itself as a “militia.” This is a loose usage of the term militia, which generally refers to citizens trained as soldiers (as opposed to professional soldiers), but applies more specifically to a state-sponsored militia that is part of the state’s armed forces but subject to call only in emergency. To avoid confusion, the TC 7-100 series uses militia only in the latter sense.

Guerrilla Brigades

The composition of the guerrilla brigadeis flexible. A basically rural, mountainous, or forested area with no major population centers might have a guerrilla brigade with only one or two battalions (or five or six companies) with little or no additional combat support or combat service support. A guerrilla brigade operating astride a major avenue of approach, or one that contains several major population (urban) or industrial centers, might be a full guerrilla brigade with additional combat support or combat service support elements. (See TC 7-100.3.)

Unit structure is closely aligned to a military-like organization and its subordinate echelons. Typical composition of a fully organized guerrilla brigade may be as follows:

- Brigade headquarters.

- Three or more guerrilla battalions.

- Weapons battalion.

- Reconnaissance company.

- Sapper company.

- Transport company.

- Signal platoon.

- Medical platoon.

Guerrilla Battalions

A brigade-sized guerrilla force may not be feasible; however—a guerrilla battalion or a task- organized battalion may be an available level of capability. A guerrilla battalion may be any combination of guerrilla companies or guerrilla H/K companies. When a battalion consists predominantly of guerrilla H/K companies, it may be considered a guerrilla hunter-killer (H/K) battalion. A typical task-organized- battalion might have four or five guerrilla H/K companies, organic battalion units, and a weapons battery from brigade (with mortar, antitank, and rocket launcher platoons) and possibly intelligence and electronic warfare (IEW) support.

Battalion structure is flexible. However, composition of a typical guerrilla battalion is as follows:

- Battalion headquarters.

- Guerrilla companies or guerrilla HK companies.

- Weapons company.

- Reconnaissance platoon.

- Sapper platoon.

- Transport platoon.

- Signal section.

- Medical section.

Guerrilla Companies

The guerrilla company fights with platoons, squads, and fire teams. When organized for combat as a guerrilla H/K company, it fights with H/K groups, sections, and teams. The guerrilla H/K company is simply a restructured guerrilla company. They both contain the same number of personnel and similar equipment. Complete battalions and brigades or selected subordinate units can be organized for combat as H/K units.

The typical guerrilla H/K company is organized into three H/K groups. Each group has four sections of three H/K teams each. This company structure contains a total of 36 H/K teams. There can be 39 H/K teams if the two sniper teams and the company scouts in the company’s headquarters and command section are configured as H/K teams.

The guerrilla H/K company is especially effective in restrictive terrain and close environments (such as urban, forest, or swamp). The task-organized H/K team structure is ideal for dispersed combat operations. H/K teams can easily disperse within an area of operations and conduct coordinated or semi- independent actions.

Company structure is flexible. A typical guerrilla company consists of—

- Headquarters and service section.

- Three guerrilla platoons

- Weapons platoon.

Criminal Organizations

Criminal organizations are normally independent of threat control and large-scale organizations often extend beyond national boundaries to operate regionally or worldwide. Individual criminals or small-scale criminal organizations (gangs) do not typically have the capability to adversely affect legitimate political, military, and judicial organizations. Large-scale organizations can demonstrate significant capabilities adverse to legitimate governance in an area, region, nation, and/or transnational influence. The weapons and equipment mix varies, based on type and scale of criminal activity. Criminal organizations can take on the characteristics of a paramilitary organization. (See TC 7-100.3.)

By mutual agreement and when their interests coincide, criminal organizations may become affiliated with other non-state paramilitary actors such as insurgent organization or guerrilla unit. Insurgents or guerrillas controlling or operating in the same area can provide security and protection to the criminal organization’s activities in exchange for financial assistance or arms. Guerrilla or insurgent organizations can create diversionary actions, conduct reconnaissance and early warning, money laundering, smuggling, transportation, and civic actions on behalf of the criminal organization. Their mutual interests can include preventing state forces from interfering in their respective spheres.

Criminal organizations might also be affiliated with threat military and/or paramilitary actors. A state, in a period of war or during clandestine operations, can encourage and materially support criminal organizations to commit actions that contribute to the breakdown of civil control in a neighboring country.

Other Combatants

Armed Combatants

In any OE, there will be nonmilitary personnel who are armed but not part of an organized paramilitary organization or military unit. Some of these nonaffiliated personnel may possess small arms legally to protect their families, homes, and/or businesses. Some might only be opportunists who decide to attack a convoy, a vehicle, or a soldier in order to make a profit. Motives might be economic, religious, racial, cultural differences, or revenge, hatred, and greed.

Armed combatants may represent a large segment of undecided elements in a relevant population. An event prompting support to the OPFOR might be the injury or death of a family member, loss of property, or the perceived disrespect of their culture, religion, or social group. Armed combatants might change sides several times depending on the circumstances directly affecting their lives.

Some armed noncombatant entities can be completely legitimate enterprises. However, some activities can be criminal under the guise of legitimate business. The irregular OPFOR can embed operatives in legitimate commercial enterprises or criminal activities to obtain information and/or capabilities not otherwise available to it. Actions of such operatives can include sabotage of selected commodities and/or services. They may also co-opt capabilities of a governing authority infrastructure and civil enterprises to support irregular OPFOR operations.

Unarmed Combatants

The local populace contains various types of unarmed nonmilitary personnel who, given the right conditions, may decide to purposely and materially support the OPFOR in hostilities against an enemy. This active support or participation may take many forms, not all of which involve possessing or using weapons. For example, in an insurgent organization unarmed personnel might conduct recruiting, financing, intelligence-gathering, supply-brokering, transportation, courier, or information warfare functions (including videographers and camera operators). Technicians and workers who fabricate IEDs might not be armed. The same can be true of people who knowingly provide sanctuary for combatants. Individuals who perform money-laundering or operate front companies for large criminal organizations might not be armed. Individual criminals or small gangs might be affiliated with a paramilitary organization and perform support functions that do not involve weapons.

Examples can include unarmed religious, political, tribal, or cultural leaders who participate in or actively support the OPFOR. Unarmed media or medical personnel may become affiliated with a military or paramilitary organization. Unarmed individuals who are coerced into performing or supporting hostile actions and those who do so unwittingly can, in some cases, be categorized as combatants. From the viewpoint of some governing authorities attempting to counter an OPFOR, any armed or unarmed person who engages in hostilities, and/or purposely and materially supports hostilities against the governing authority or its partners might be considered a combatant.

Noncombatants

Noncombatants are persons not actively participating in combat or actively supporting of any of the forces involved in combat. They can be either armed or unarmed. Many noncombatants are completely innocent of any involvement with the OPFOR. However, the OPFOR will seek the advantage of operating within a relevant population of noncombatants whose allegiance and/or support it can sway in its favor. This can include clandestine yet willing active support (as combatants), as well as coerced support, support through passive or sympathetic measures, and/or unknowing or unwitting support by noncombatants. (See TC 7-100.3)

The TC 7-100.4 online directories also include nonmilitary actors that are not part of the HTFS but might be present in the OE. As noncombatants, they are currently either friendly or neutral. They can be either armed or unarmed, and have the potential to become combatants in certain conditions. They might provide support to combatants—either as willing or unwilling participants.

The irregular OPFOR recognizes that noncombatants living and/or working in an area of conflict can be a significant source of—

- Intelligence collection.

- Reconnaissance and surveillance.

- Technical skills.

- General logistics support.

The irregular OPFOR actively attempts to use noncombatants within a relevant population to support its goals and objectives. It sees them as a potential multiplier of irregular OPFOR effectiveness. It will also attempt to use the presence of noncombatants to limit the effectiveness of its enemies. The irregular OPFOR can marshal and conceal its combatant capabilities while hiding among armed and unarmed noncombatants in a geographic or cyber location.

Armed Noncombatants

In any OE, there will be nonmilitary individuals and groups who are armed but are not part of an organized paramilitary or military structure. Some may be in possession of small arms legally to protect their families, property, and/or businesses. Some may use weapons as part of their occupation (for example, hunters, security guards, or local police). Some may be minor criminals who use their weapons for activities such as extortion and theft; they might even steal from U.S. forces, to make a profit. They may be completely neutral or have leanings for either side, or several sides. However, they are not members of or directly affiliated with a hostile faction. Their numbers vary from one individual to several hundred. Given the fact that they are already armed, it would be easy for such noncombatants to become combatants, if their motivation and commitment changes.

Some armed noncombatant entities can be completely legitimate enterprises. However, some activities can be criminal under the guise of legitimate business. The OPFOR can embed operatives in legitimate commercial enterprises or criminal activities to obtain information and/or capabilities not otherwise available to it. Actions of such operatives can include sabotage of selected commodities and/or services. They may also co-opt capabilities of a governing authority infrastructure and civil enterprises to support irregular OPFOR operations

Examples of armed noncombatants commonly operating in an OE are—

- Private security contractor (PSC) organizations.

- Local business owners and employees.

- Private citizens and private groups authorized to carry and use weapons.

- Criminals and/or organizations with labels such as cartels, gangs.

- Ad hoc local “militia” or “neighborhood watch” programs.

As one example, private security contractors (PSCs) are commercial business enterprises that provide security and related services on a contractual basis. PSCs are employed to prevent, detect, and counter intrusions or theft; protect property and people; enforce rules and regulations; and conduct investigations. They may also be used to neutralize any real or perceived threat. PSCs can act as an adjunct to other security measures and provide advisors, instructors, and support and services personnel for a state’s military, paramilitary, and police forces. They may also be employed by private individuals and businesses (including transnational corporations). PSCs are diverse in regard to organizational structure and level of capability. The weapons and equipment mix is based on team specialization/role and varies. Other example equipment includes listening and monitoring equipment, cellular phones, cameras, facsimiles, computers, motorcycles, helicopters, all-terrain vehicles, antitank disposable launchers, submachine guns, and silenced weapons.

Unarmed Noncombatants

Other actors in the OE include unarmed noncombatants. These nonmilitary actors may be neutral or potential side-changers in a conflict involving the irregular OPFOR. Their choice to take sides depends on their perception of who is causing a grievance for them. It also depends on whether they think their interests are best served by supporting a governing authority. Given the right conditions, they may decide to purposely support hostilities against a governing authority that is the enemy of the OPFOR. Even if they do not take up arms, such active support or participation moves them into the category of unarmed combatants. (See TC 7-100.3.)

Some of the more prominent types of unarmed noncombatants are—

- Media personnel.

- Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

- Transnational corporations and their employees.

- Private citizens and groups.

However, unarmed noncombatants may also include internally displaced persons, refugees, and transients. They can also include foreign government and diplomatic personnel present in the area of conflict. Examples of common types of unarmed noncombatants can also be found in the organizational directories. These include medical teams, media, humanitarian relief organizations, transnational corporations, displaced persons, transients, foreign government and diplomatic personnel, and local populace. These nonmilitary actors may be neutral or potential side-changers depending on OE conditions as they change.

Section V - Organizational Directories

This organization guide is linked to online organizational directories, which TRADOC G2, ACE, Threats (ACE-Threats) maintains and continuously updates, as necessary, to represent contemporary and emerging capabilities. These directories provide a comprehensive menu of the numerous types of Threat organizations in the detail required for the Army’s live, virtual, and constructive training environments. To meet these various requirements, the directories contain over 10,000 pages of organizational information, breaking out most Threat units down to squad-size components. However, some training simulations either cannot or do not need to portray Threat units down to that level of resolution. From this extensive menu, therefore, trainers and training planners can select and extract only the units they need, in the appropriate level of detail for their specific training requirements.

Note. The organizations in these directories do not constitute a threat order of battle (OB). However, trainers and training planners can use these organizational building blocks to construct a threat OB that is appropriate for their training requirements. To do so, it will often be necessary to create task organizations from the available building blocks. It may also be necessary to substitute different pieces of equipment for those listed for units in the organizational directories.

The organizational information contained in the directories exceeds the scope and size that can be accommodated within a traditional FM format. The magnitude of task-organizing an exercise order of battle also requires that users have the ability to use downloaded organizations in an interactive manner. For these reasons, it is necessary for this FM to be linked to organizational diagrams and associated equipment inventories made available in electronic form that users can download and manipulate as necessary in order to create task organizations capable of fighting in adaptive ways that typify the OE.

Note. For illustrative purposes, this FM contains several examples from the online HTFS organizational directories. Readers are reminded that even the baseline HTFS organizations are subject to change over time. Therefore, readers should always consult the online directories for the latest, most up-to-date versions of organizational data.

Online directories of organizations in the HTFS are accessible by means of the following link to the Army Training Network portal: https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=311; then click on the particular organization needed for that portion of the threat force structure. If the user is already logged into AKO (by user name and password or by Common Access Card login), no further login may be necessary.

The directories consist of four volumes: Divisions and Divisional Units; Nondivisional Units; Paramilitary and Nonmilitary Actors; and Other. These directories are maintained and continuously updated, as necessary, by the TRADOC G2, ACE, Threats (ACE-Threats), in order to represent contemporary and emerging capabilities. The TRADOC G-2, ACE Threats is designated as “the responsible official for the development, management, administration, integration, and approval functions of the OPFOR Program across the Army” (AR 350-2).

The role of these directories is to provide a menu of Threat units to use in task-organizing to stress U.S. Army training. These directories do not constitute an order of battle (OB) but rather a menu of capabilities. Chapter 3 provides guidance on how to task-organize the Hybrid Threat from the pieces contained in the online directories. In some cases, task-organizing may not be required (particularly at lower tactical levels), and fighting organizations may be lifted directly from the HTFS. However, it is often necessary to tailor these standard organizations into task organizations better suited for training requirements.

There is no such thing as a standard structure for major operational-level commands in the HTFS: corps, armies, army groups, military districts, or military regions. Therefore, the online directories provide only the organizational structures for the types of units likely to be found in one of these echelons-above- division commands in the peacetime HTFS. In an OPFOR OB, some of these units will have become part of a task organization at operational or tactical level.

Files for OPFOR Units

The architectural build of the HTFS units located on the ATN website is simple and straightforward. The organizations were built from the bottom up, solely for trainers and planners to use to select and build Threat organizations to execute Hybrid Threat countertasks. The build for the organizational directories started at the lowest level, breaking out the organization, personnel, and equipment down to squad-size components, since some training simulations may require that level of resolution. If some trainers or training planners do not require that level of detail, they can extract from the organizational directories the entries starting at the lowest level that is required for their particular exercise OB.

All of the Threat organizations listed in the HTFS organizational directories on ATN are constructed using known software so the trainer could tailor and/or task-organize them individually or collectively to meet specific training and/or simulation requirements. Most trainers and simulators have software available and a basic knowledge of its use. See appendix B for detailed instructions that should enable a trainer with only a basic knowledge of to build a task-organized structure using available software.

The basic entry for each organization is built in a document. This Document provides details for the Threat organization and contains four basic sets of information: unit name, organizational graphics, personnel information, and principal items of equipment (unless personnel and equipment are listed in a separate spreadsheet). For examples, see appendix D, which contains the complete entries for the motorized infantry company and the personnel and equipment spreadsheets for the motorized infantry battalion as they appear in the HTFS organizational directories on ATN.

Unit Name

The name of the unit appears in a heading at the top of each page in the organizational directory. Each or file name includes the name of the highest unit described in that file.

The names of some units (usually battalions or companies) in the HTFS organizational directories are followed by the label “(Div)” or “(Sep).” Here, “(Div)” indicates that the battalion or company in question is the version of its type organization normally found at division level in the HTFS. Separate brigades in the HTFS have some subordinates that are the same as at division level and are therefore labeled “(Div).” Other subordinates that are especially tailored to the needs of a separate brigade are labeled “(Sep).” Any subordinates of a separate brigade that are the same as their counterparts in a divisional brigade do not have either of these labels. Units with “(Sep)” following their names are not separate battalions or separate companies. To avoid confusion, any unit that is actually “separate” would have the modifier “Separate” (or abbreviated “Sep”) preceding its name rather than following it.

Some units (usually brigades and battalions) could have the label “(Nondiv)” following their names in order to identify them as “nondivisional” assets (not subordinate to a division). Other units with the same basic name may have the label “(Div)” to distinguish them as being “divisional” (subordinate to a division). For example, the Materiel Support Brigade (Nondiv) has a different structure from the Material Support Brigade (Div).

Organizational Graphics

The organizational graphics are built in known software and then inserted into a document. The organizational charts for specific organizations in the online directories depict all possible subordinate units in the HTFS. Aside from the basic organization, the organizational directory entry for a particular unit may contain notes that indicate possible variations and alternatives.

Note. Some of the graphics in this TC are based on graphics in the online organizational directories. In the process prescribed for FM publication, however, they may have been converted to another format and thus can no longer be opened or manipulated as objects. If users of this TC need these graphics, they will have to go to the organizational directories on the Army Training Network (ATN) Website at https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=311 .

Organization charts in the online directories display units in a standard line-and-block chart format. These charts show unit names as text in a rectangular box (rather than using “enemy” unit symbols in diamonds, as is often the custom in Threat OBs for training exercises). There are a number of reasons for this, mostly in the interest of clarity: The Threat has some units whose nature and names (appropriate to their nature) do not correspond directly to unit symbols in ADRP 1-02, which are designed primarily for depicting the nature of U.S. units. Therefore, the use of text allows organizational charts to be more descriptive of the true nature of Hybrid Threat units. The space inside a rectangular box is better suited than a diamond for showing the unit names as text, thus allowing organization charts to display a larger number of subordinate units in a smaller space.

Personnel and Equipment Lists

For each unit, the organizational directories provide a very detailed listing of personnel and equipment. For some training requirements, the Threat OB might not need to include personnel numbers. A particular OB might not require a listing of all equipment, but only major end items. In such cases, trainers and training planners can extract the appropriate pages from the organizational directories and then simplify them by eliminating the detail they do not need. However, the directories make the more detailed version available for those who might need it.

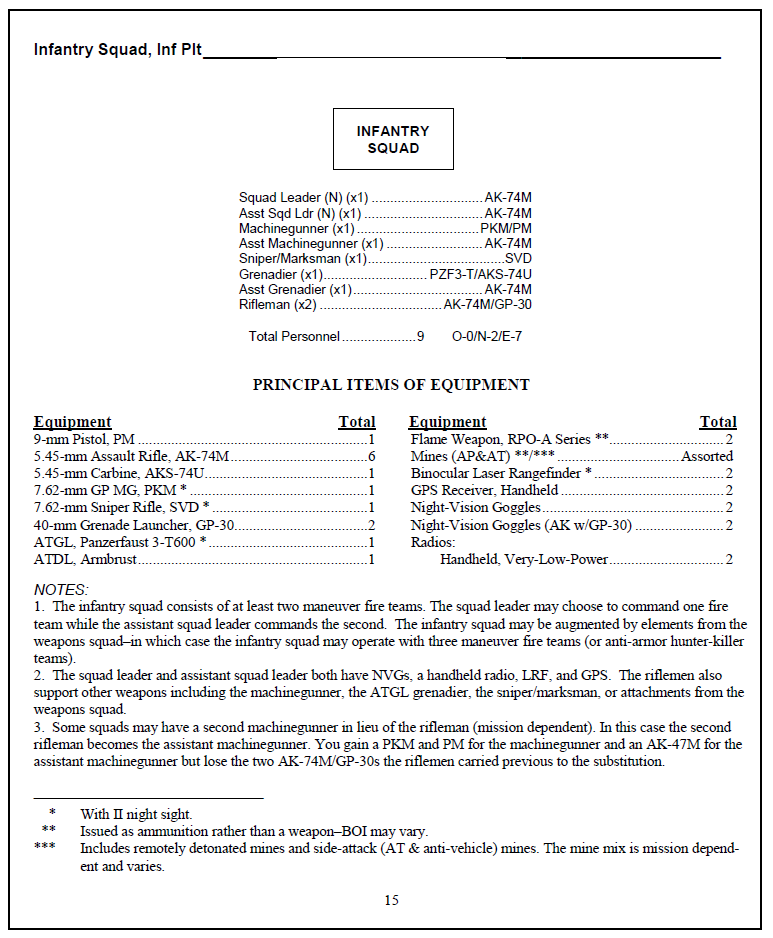

At the lowest-level organizations (for example, infantry squad), where the organizational chart does not show a unit breaking down into further subordinate units, the organizational directories list individual personnel with their individual weapons. (Figure 2-4 shows the example of an infantry squad, taken from page 15 of the Document for the motorized infantry battalion in the HTFS organizational directories. See appendix D for additional details on the motorized infantry platoon, company, and battalion.) At this level, each individual’s duty title/position/function is identified for all Threat personnel organic to the organization described. The duty title is followed by the individual’s rank category:

- (O) = Officers (commissioned and warrant).

- (N) = Noncommissioned officers.

- ( ) = Enlisted personnel. This is usually blank and reflected only in the personnel totals.

Note. Charts for insurgent organizations are the exception, since they do not show personnel broken down into the three rank categories. Insurgents are not part of a formalized military structure and are therefore not broken down by rank. See appendix C for an example of insurgent organization. For additional information on insurgents, see TC 7-100.3.

Directly following the individual’s title and rank category is the number of personnel occupying that position, such as (x1) or (x2). This is followed by the nomenclature of the individual’s assigned personal weapon, such as AK-74M or SVD. In some cases, an individual may have two assigned weapons; for example, an individual assigned a 7.62-mm GP MG, PKM may also be assigned a 9-mm Pistol, PM. This reads as PKM/PM in the listing. In some instances, the individual also serves as the gunner/operator of a weapon—this is also identified. In figure 2-4, for instance, the Grenadier (x1) is the gunner/operator of the ATGL, Panzerfaust 3-T600. His personal weapon is the 5.45-mm Carbine, AKS-74U. The Riflemen (x2) are assigned the 5.45-mm Assault Rifle, AK-74M with the 40-mm Under-Barrel Grenade Launcher, GP-30 (similar to the U.S. M16/M203).

Personnel totals for a unit are listed below the detailed listing of individual personnel and their equipment (or directly below the organizational chart for larger units). The first number reflects the total personnel in that organization. The second set of numbers breaks down the total number of personnel by rank category. In this case, “E” is used for enlisted personnel. In figure 2-4 on page 2-17, for example, the personnel for the infantry squad indicate that there are no officers, two noncommissioned officers, and seven enlisted personnel—for a total of nine personnel.

For organizations from the lowest levels up through battalion level (in some cases up to brigade level), the basic entry in the HTFS organizational directories includes a listing of “Principal Items of Equipment.” This list gives the full nomenclature for each item of equipment and the total number of each item in the unit. Figure 2-4 on page 2-17 shows an example of this for the infantry squad.

Some weapons are issued as a munition rather than an individual’s assigned weapon. An example of this is the Flame Weapon, RPO-A Series (see figure 2-4 on page 2-17). Generally, a footnote accompanies these weapons, stating that they are issued as ammunition rather than a weapon—therefore the basis of issue (BOI) may vary. Anyone in the unit might fire these weapons, and the numbers of these weapons in an organization vary. Often they are carried in a vehicle, or kept on hand, until needed.

Sometimes a weapon is not assigned a gunner. In this case, a note generally describes the relationship. Some organizations, especially Special-Purpose Forces, have a wide selection of weapons and equipment available due to their multipurpose mission capability. The final selection of weapons and equipment is determined by the specific mission required at the time. These weapon and equipment numbers are easily adjusted using and/or.

Note. Some of the graphics in this TC are based on spreadsheets in the online organizational directories. In the process prescribed for FM publication, however, they may have been converted to another format and thus can no longer be opened or manipulated as objects. If users of this TC need these spreadsheets in form, they will have to go to the organizational directories on the Army Training Network (ATN) Website at https://atn.army.mil/dsp_template.aspx?dpID=311.

For larger organizations, personnel and equipment numbers are listed in spreadsheets. There is a vertical column for each subordinate unit and a horizontal row for each item of equipment, with an automatically summed total at the right end of each row for the total number of each item of equipment in the overall organization. When the overall organization contains multiples of a particular subordinate unit, the unit designation at the top of the column indicates the number of like units (for example, “Hunter/Killer Groups (x3)” for the three hunter/killer groups in a hunter/killer company of a guerrilla battalion). In the interest of space, however, the spreadsheet format is not used for smaller units. Instead, they list “Total Personnel” and “Principal Items of Equipment” as part of the document. Brigades and some battalions list personnel and equipment in both formats.

Footnotes

Footnotes apply to lists of personnel and equipment, in either or format. Each footnote has a number of asterisks that link it to footnote reference with the same number of asterisk in the equipment list. Some footnotes explain—

- Characteristics of a piece of equipment (for example, “* With thermal sight”).

- Why the total for a particular item of equipment is flexible (for example, ** Issued as ammunition rather than a weapon—the BOI varies”).

- The types of weapons or equipment that might be included under “Assorted.”

- Possible equipment substitutions and their effect on personnel numbers.

In a spreadsheet, footnotes with reference asterisks in the top row of a column can provide information about the subordinate unit in that column. Most often, this type of footnote explains that the equipment numbers in that column have already been multiplied to account for multiple subordinates of the same type. For example, the reference “Motorized Infantry Company (x3)*” is linked to a footnote that explains: “* The values in this column are the total number for three companies.” Other footnotes serve the same purposes as in a document.

Notes

Notes in a Document generally apply to the organization as a whole or its relationship with other organizations. Occasionally, they provide additional information on a particular part of the organization. In either case, notes are numbered (unless there is only one), but the number is not linked to a particular part of the organization. Various types of notes can explain—

- The nature of the organization and possible variations in its structure.

- Possible augmentation with additional equipment.

- Personnel options. For example: “Some squads may have a second machinegunner in lieu of a rifleman (mission dependent).”

- Unit capabilities or limitations. For example: “The infantry platoon has sufficient assets to transport the platoon headquarters and weapons squad. It is dependent upon augmentation from higher (battalion transport platoon) to transport the three infantry squads over distance.”

- Which personnel man a particular weapon or piece of equipment.

- How units or personnel are transported.

- How a unit or subordinate is employed and the types of tactics used.

- How assets of one subordinate can be allocated to other subordinates.

Especially for paramilitary and nonmilitary entities, notes describe various possible mixtures of personnel, equipment, and subordinates that might occur. Notes may reference another manual in the 7-100 series for more information regarding the organization described.

Folders for Threat Force Structure

The organizational directories of the HTFS are contained in four volumes. Each volume is divided into folders that contain the unit files. These folders and files serve as the menu for threat baseline units. Many of the baseline Hybrid Threat Force Structure (HTFS) is located on the Army Training Network (ATN) for ease of access and use. The HTFS organizational directories are continually updated on the ATN; therefore, the listing below is dynamic. Over time, additional units will be added and existing units will be modified and updated, as necessary, to represent contemporary and emerging capabilities. Although the list of threat units may change, the basic architecture of the organizational directories will remain essentially the same. Figure 2-5 on page 2-22 shows the basic listing of folders in the organizational directories. For a more detailed listing of folders and files for threat units in the TFS organizational directories, see appendix A.