Time: Otso

DATE Europe > Otso > Time: Otso ←You are here

Time Overview

Originally, the easternmost territory of the Skolkan Empire, by the early 18th Century the region that now comprises the countries of Bothnia and Otso had acquired a considerable degree of autonomy. Increasingly autonomous as the century wore on, the local aristocracy gained considerable wealth from the sale of timber for spars and masts to the navies of the warring factions during the Napoleonic wars. Although the Empire was allied with Donovia during the wars, the eastern region was essentially on the sidelines as being too geographically isolated from the main areas of conflict. The Dukes of Northern Bothnia, South Bothnia and Otso used the Empire’s distraction with the wars to gain further autonomy from the Skolkan capital in Tyr, sometimes in collaboration with each other and sometimes in competition. As the Empire gradually became moribund, the Dukes became more and more independent. During this period, the Court of Bothnia maintained a close relationship with the Donovian Court and their small but loyal contribution during the Napoleonic years was not to be forgotten. By the time of the First World War (WWI), the region was to all intents and purposes an independent state drawing little attention from either Skolkan rulers, or their Donovian neighbors to the east.

Throughout the 19th Century, the region prospered, largely through exports of timber and fur. Partly as a result of this and partly as a result of its comparative geographic position, there was nothing like the scale of industrialization in Skolkan that the rest of northern Europe experienced during this period. By the outbreak of WWI, Otso and North Bothnia were essentially backwaters, while the southern part of Bothnia expanded considerably along the coastline and the Duke’s seat, Brahea, reached its zenith by 1880 as a cultured and rich city although shaded regionally by St Petersburg. By 1914, the Duchy of South Bothnia was a relatively rich entity. During the war, the Skolkan Empire was nominally neutral, but there were a variety of factions throughout the region that favored either Donovia or the Central Powers. Both of the Bothnian Duchies and the Duchy of Otso provided volunteer regiments to the Donovian army as well as other assistance to the Donovian war effort. The collapse of Donovia into chaos in 1917 triggered the final collapse of the Empire. Royalists, republicans, separatists, communists and proto-fascists fought a confused civil war. The close relationship with Donovia produced a divided country as factions fought for separate political Ideologies. Finally, faced with an uncertain neighbor in Donovia, the eastern duchies combined to form a single state as the Republic of Otsobothnia, whose legitimacy was recognized as part of the overall post WWI settlement in Europe. However, although this made geographic sense, it was not a natural entity as the Duchies had a sense of “self” that was distinct and to a degree antagonistic.

External relations with Torrike and Framland were acceptable, not least because the main focus of those countries was internal, or in the case of Torrike, concentrated on the more pressing problem of an independent but weak Arnland on its southern border. Internally, considerable tension remained. South Bothnia was a hive of communist activity and sympathizers and the Duke and his family were forced to abandon their holdings. North Bothnia was quieter, but still suffered some degree of disruption; the death of the last hereditary Duke may have relieved tension somewhat. Within the confines of his territory, the Duke of Otso remained influential and carefully steered a more democratic approach to politics. The fault lines along which Otsobothnia would ultimately split were actually apparent from the very foundation of the country. After a great deal of violent confrontation, Otsobothnia eventually settled down as a marginally democratic state, albeit one in which there were significant political tensions. The communist party remained a force in the south and west, while the east remained more traditional in its outlook.

Donovia recognized Otsobothnia as an independent state and acknowledged their mutual borders. However, despite several treaties and non‐aggression agreements, tensions arose during the 1930s. Soviet acceptance of Otsobothnia declined with the distance from the Soviet Revolution. The revolution the Soviets anticipated in Otsobothnia never took place; communistic parties and their sympathizers were not successful electorally and active agitators were suppressed. Additionally, Donovia grew increasingly concerned about the vulnerability of Leningrad and sought to improve its defenses by pushing back the borders. Donovia offered Otsobothnia a land swap to increase Otsobothnia’s territory in the North, while conceding land in the area of Leningrad. This would have increased the actual size of Otsobothnia while pushing its border in the Karelian Isthmus back to within 30km of Viipuri. This offer was discussed several times, but rejected on each occasion.

In August 1939, Donovia signed a non‐aggression treaty with Nazi Germany, the so called Molotov‐Ribbentrop pact. A hidden codicil to this pact delineated “spheres of influence” between Donovia and Germany. Under this agreement, the Baltic states and the eastern half of Otsobothnia fell under Donovia. After the successful division of Poland, Donovia turned its attention once more to Otsobothnia. The new territorial demands were even less attractive than before, with additional concessions being required from Otsobothnia. These would, in effect, have denuded the country of its defensive fortifications against Donovia. When these demands were rejected, the Donovians invaded. Although they were ultimately victorious, the war showed up serious shortcomings in the Donovian army which suffered heavy losses. The final settlement pushed Donovia’s borders well to the west of Viipuri. When Hitler invaded Donovia in 1941, Otsobothnia seized the opportunity to reclaim its lost territory. Otsobothnian aims were limited to regaining lost ground and they refused to be drawn beyond these bounds, despite German pressure. Otsobothnia, for instance, did not participate in the siege of Leningrad and refused to cut the Murmansk railway. The Donovian offensive of 1944 drove the Otsobothnian forces back to their start point and an Armistice was signed in 1944.

The final settlement of the conflict and formal cessation was war was ratified under the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947. Under this settlement, Otsobothnia lost the Karelian regions and had to pay a huge war indemnity of approximately 50% of the country’s GDP. The final border with Donovia was well to the north and west of Viipuri. Negotiations after the cease‐fire exacerbated existing tensions between the Otsonians and the western provinces. The strong sense of self helped crystallize the belief that the “westerners” took all the wealth of the country while the east made all the sacrifices. The loss of Viipuri and associated territory deprived the east of one of its few industrial centers and further increased the east’s sense of grievance. Encouraged by the Donovians, Otso declared itself to be independent as the Royal Duchy of Otso, which they declared would be a neutral state along the lines of Switzerland. This proposal actually suited the western provinces, which accepting that it would not be possible to regain territory lost to Donovia, assessed that the eastern provinces would be a drain on their resources. Additionally, a buffer between Donovia and their provinces would give them more room for maneuver in rebuilding their state. As a result, the creation of Bothnia and Otso as independent states became part of the overall settlement of the Second World War (WWII).

Key Dates, Time Periods, or Events

- 1905 – Norway declared independence from the Skolkan Empire

- 1917 – Civil war within the Skolkan Empire.

- 1920 – Skolkan Empire formally dissolved. Arnland, OtsoBothnia, and Torrike formed as separate countries.

- 1947 – Paris Peace Treaty of 1947 leads to establishment of the Royal Duchy of Otso.

- 1948 – The Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance is signed between Donovia and Otso.

- 1951 – Borders between Bothnia and Otso were formalized.

- 1955 – Otso joined the United Nations (UN) and the Nordic Council.

- 1982 – The Transit Agreement and the Basic Treaty were negotiated between Bothnia and Otso.

- 1990 – Gulf of Bothnia Cooperation Council (GBCC) founded by Bothnia and Torrike. Otso became a signatory.

- 1997 – GBCC members sign an economic cooperation framework.

- 1999 – The Act of the Openness of Government Activities, Personal Data Act and Act on Protection of Privacy and Data Security in Telecommunications enabled the expansion of the internet space.

- 2001 – Homeland Defense (2000) Act came into force requiring male and female conscription.

- 2005 – GBCC Interbank established

Routine, Cyclical Key Dates

Public Education

Education is compulsory for nine years starting at age seven. Education after primary school divides into vocational and academic systems. More details are in the Social Variable.

National and Religious Holidays

Otso observes all Christian holidays, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. National holidays and observances include the following:

- Spring Equinox – March Equinox

- May 01 – May Day

- Second Sunday in May – Mother’s Day

- Day before Summer Solstice – Midsummer Eve

- Summer Solstice – Midsummer Day

- Autumnal Equinox – September Equinox

- Second Sunday of November – Father’s Day

- Winter Solstice – December Solstice

Harvest Cycles

The growing season lasts 240 days in the south and 100 days in the north. See Physical Environment Variable for more information.

Elections

The political parties are elected by popular vote for a five‐year term; the Duke appoints the prime minister and deputy prime minister from the majority party or the majority coalition after parliamentary elections. More detail can be found in the Political Variable.

Military Training

Otso runs a full conscription system under which all adults between the ages of 18 and 30 are liable for National Service. Conscripts can serve in a number of capacities, including Civil Defense, Emergency Services, and Social Services as well as the military. Conscripts are inducted into the military twice per year, with four months on basic training followed by six months in their designated specialization. The period of service can be deferred if the individual is in an essential occupation, or full time education, but National Service must be completed by their 30th birthday. Conscripts who volunteer for service in an International Operation must have served at least eight months of their national service and have an acceptable performance record. Once selected for International Operations, they are transferred to the regular establishment for the duration of their training, deployment and post deployment recovery period. This can be up to two years, depending on the operation.

On completion of National Service, Otsans are required to undertake a number of days refresher training every year; the commitment varies with specialization and role. Members of the High Readiness Reserve perform the equivalent of 56 days training per year, while those in other formations are liable for only 22 days per year.

For more information, see Military Variable.

Government Planning

The Otsan government fiscal year is the calendar year.

Cultural Perception of Time

Otso has one time zone. The country observes Eastern European Time (EET). Otso is GMT/UTC + 2h during Standard Time, and GMT/UTC + 3h during Daylight Saving Time. In Europe daylight saving time is often referred to as "Summer Time."

Arctic Perception of Time

The Arctic is an enormous area, sprawling over one sixth of the earth's landmass; twenty‐four time zones and more than 30 million km2. The Arctic is inhabited by some four million people, including more than 30 indigenous peoples of which the Sami are resident in Otso. Sami knowledge is based on experience in that knowledge was not obtained from a book or taught in classroom, but rather it was accumulated through repeated experiences of particular situations. Sami time is based on the cycles of nature, particularly the yearly cycle of the reindeer.

Sami concept of seasons are based on the eight reindeer life-cycles and prevailing weather conditions.

| Season | Explanation |

| Spring-Winter | The herd begins the migration from the forests to the calving grounds in the mountains. |

| Spring | The temperature increases and the snow begins to melt. Reindeer calves are born. |

| Pre-Summer | The reindeer graze and the Sami have some time to rest and prepare for the earmarking of the calves. |

| Summer | Much of this season is bathed in twenty-four hour per day sunlight. During this time, earmarking takes place to denote ownership. |

| Pre-Autumn | The Sami begin to prepare for the harsh winter by choosing the bull reindeer destined for slaughter. |

| Autumn | This is the season of rut. The reindeer mate prior to their return to the winter-grounds. |

| Pre-Winter | The herders lead the reindeer out of the mountains to the lowland bogs. |

| Winter | Under a cover of twenty-four hour per day darkness, the Sami move the reindeer to the forest, the last place to find enough food to support the herd. |

The Sami divide their year into 12 months like the Western calendar. However, these are not set by a specific number of days. They are based on natural phenomena.

| Western | Sami | Meaning |

| January | Ođđajagemánnu | New Year Month |

| February | Guovvamánnu | Unknown |

| March | Njukčamánnu | Swan Month |

| April | Cuoŋománnu | Snow Crust Month |

| May | Miessemánnu | Reindeer Calf Month |

| June | Geassemánnu | Summer Month |

| July | Suiodnemánnu | Hay Month |

| August | Borgemánnu | Molt Month |

| September | Čakčamánnu | Fall Month |

| October | Golggotmánnu | Rut Month |

| November | Skábmamánnu | Dark-Period Month |

| December | Juovlamánnu | Yule Month |

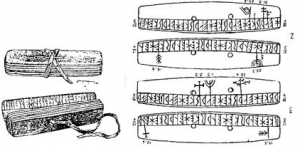

To help track these times, the Sami developed a wooden calendar in the mid-1800s. The wooden calendar is divided in weeks and is easily transportable. Typically fabricated from wood or reindeer antler, this calendar was used to keep track of both natural phenomena and religious occurrences. Written in the runic alphabet, the wooden calendar was a useful tool in helping to preserve the balance between nature and religion as they denoted events in both realms. Crosses denote days of religious significance while fish and leaf sprigs denote various events in nature. By keeping track of time in this way, the Sami could easily refer back to earlier times of the year in order to try to predict when the fishing season would be most bountiful or whether or not spring would arrive early or not.

Western Perception of Time

Western time is based on scientific calculations and observations. From the sundial to the atomic clock, time relies on such measurements as the rotation of the earth to the number of oscillations of a particular atom. These are finite measurements of time which contrast drastically with the changeable calendar of the Sami. The Western concept of time is not a product of experiential learning but rather a shared careful observation made by a relative minority of the population. Without a watch or clock, most Westerners would be unable to offer what they would consider an accurate estimate of the time. The Sami Concept of Time, by Eva [Stephanie Redding] https://www.laits.utexas.edu/sami/dieda/anthro/concept-time.htm.

| DATE Europe Quick Links . | |

|---|---|

| Arnland | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Bothnia | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Donovia-West | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Framland | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Otso | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Pirtuni | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Torrike | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Other | Non-State Threat Actors and Conditions • DATE Map References • Using the DATE |