Difference between revisions of "Time: Torrike"

(Main article for Torrike Time variable.) (Tag: Visual edit) |

m |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{:DATE Banner}} | ||

| + | <div style="font-size:0.9em; color:#333;"> | ||

| + | [[Europe|DATE Europe]] > [[Torrike]] > '''{{PAGENAME}}''' ←You are here | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="float:right;">__TOC__</div> | ||

| − | = | + | == Time Overview == |

| − | Torrike represents the heartland and remnant core of a once considerably larger and more powerful political entity, the Skolkan Empire. In the first decades of the 20th Century, the Empire slowly disintegrated as elements declared independence. This process was exacerbated by the First World War (WWI). Although neutral, the Empire did not escape the effects of the conflict and from 1917 was embroiled in a civil war. The independent countries of Arnland in the south and OtsoBothnia in the east were recognized and the Empire was formally declared dissolved in 1920. The remaining territory renamed itself Torrike, with the last Emperor Anders Munch, declared as King. However, Torrike would be a constitutional monarchy and his powers as Head of State were diminished to a purely ceremonial role, while the First Minister amassed political power as Head of the Government. The Riksted | + | Torrike represents the heartland and remnant core of a once considerably larger and more powerful political entity, the Skolkan Empire. In the first decades of the 20th Century, the Empire slowly disintegrated as elements declared independence. This process was exacerbated by the First World War (WWI). Although neutral, the Empire did not escape the effects of the conflict and from 1917 was embroiled in a civil war. The independent countries of Arnland in the south and OtsoBothnia in the east were recognized and the Empire was formally declared dissolved in 1920. The remaining territory renamed itself Torrike, with the last Emperor Anders Munch, declared as King. However, Torrike would be a constitutional monarchy and his powers as Head of State were diminished to a purely ceremonial role, while the First Minister amassed political power as Head of the Government. The Parliament (''Riksted'') moved from being a largely ceremonial establishment filled with appointees, to one which was fully elected and so provided the state with democratic respectability. |

Throughout the 1920s, Torrike struggled to come to terms with its diminished size and importance. In seeking a role in the modern world, the political establishment increasingly felt that a monarchy was anachronistic. The advent of the Great Depression and death of King Anders allowed the country to re‐establish itself as a republic, with the extension of the vote to all adult males. Torrike suffered greatly during the Depression years and there were a number of left wing factional attempts to establish a workers’ democracy, which were put down. Although the major political parties (the Unity Party; the Prosperity Party; the Neutrality Party and the Nationalist Party), were right wing and essentially authoritarian, the nascent Fascist Party was ruthlessly suppressed. | Throughout the 1920s, Torrike struggled to come to terms with its diminished size and importance. In seeking a role in the modern world, the political establishment increasingly felt that a monarchy was anachronistic. The advent of the Great Depression and death of King Anders allowed the country to re‐establish itself as a republic, with the extension of the vote to all adult males. Torrike suffered greatly during the Depression years and there were a number of left wing factional attempts to establish a workers’ democracy, which were put down. Although the major political parties (the Unity Party; the Prosperity Party; the Neutrality Party and the Nationalist Party), were right wing and essentially authoritarian, the nascent Fascist Party was ruthlessly suppressed. | ||

| Line 8: | Line 13: | ||

Torrike recovered slowly during the 1930s, with stimulus being provided through industrialization and the desire to make the country self‐sufficient in strategic industries. The recovery was helped by increasing demands for Torrikan raw materials; especially iron ore, bauxite and wolframite which were heavily purchased across Europe as the continent rearmed in the run up to the Second World War (WWII). In 1936, women were given the vote. Politically, changes of government produced few changes in policy and the country maintained the character of a center‐right, reasonably moderate, albeit slightly authoritarian, nation. Throughout WWII, Torrike was neutral and formed a Neutrality Pact with Arnland and Framland aimed at keeping the region out of the war. The neutrality was, however, biased towards Germany whose troops were given the right of passage through their territories to Norway after 1940. For most of the war, Torrike enjoyed the benefits of large exports of strategic materials to Germany, but diplomatic channels to the Allies were kept open. As it became increasingly clear that Germany would lose, so the interpretation of neutrality became more favorable to the Allies. Relations with Donovia were more complex. Although Torrike maintained its neutrality in the war between OtsoBothnia and Donovia, there was considerable sympathy for their former countrymen and volunteers and material assistance was sent to OtsoBothnia. Further assistance was provided to OtsoBothnia when it joined the German campaign against Donovia, but a greater distance was maintained from the conflict. | Torrike recovered slowly during the 1930s, with stimulus being provided through industrialization and the desire to make the country self‐sufficient in strategic industries. The recovery was helped by increasing demands for Torrikan raw materials; especially iron ore, bauxite and wolframite which were heavily purchased across Europe as the continent rearmed in the run up to the Second World War (WWII). In 1936, women were given the vote. Politically, changes of government produced few changes in policy and the country maintained the character of a center‐right, reasonably moderate, albeit slightly authoritarian, nation. Throughout WWII, Torrike was neutral and formed a Neutrality Pact with Arnland and Framland aimed at keeping the region out of the war. The neutrality was, however, biased towards Germany whose troops were given the right of passage through their territories to Norway after 1940. For most of the war, Torrike enjoyed the benefits of large exports of strategic materials to Germany, but diplomatic channels to the Allies were kept open. As it became increasingly clear that Germany would lose, so the interpretation of neutrality became more favorable to the Allies. Relations with Donovia were more complex. Although Torrike maintained its neutrality in the war between OtsoBothnia and Donovia, there was considerable sympathy for their former countrymen and volunteers and material assistance was sent to OtsoBothnia. Further assistance was provided to OtsoBothnia when it joined the German campaign against Donovia, but a greater distance was maintained from the conflict. | ||

| − | Post WWII, Torrike sought to build on the Neutrality Pact with their neighbors, but both countries resisted Torrikan efforts to influence them. Throughout the 1950s, the moderate Prosperity Party was in power and built the foundations of Torrike’s modern industrial success. By the 1960s, the failure to promote new talent within the Party and complacency led to increasing disillusion with the Party and its politics. A Unity/Nationalist Coalition was elected in 1967 on the promise of “Renewal” and rebuilding pride in the country and its heritage. The first signs of | + | Post WWII, Torrike sought to build on the Neutrality Pact with their neighbors, but both countries resisted Torrikan efforts to influence them. Throughout the 1950s, the moderate Prosperity Party was in power and built the foundations of Torrike’s modern industrial success. By the 1960s, the failure to promote new talent within the Party and complacency led to increasing disillusion with the Party and its politics. A Unity/Nationalist Coalition was elected in 1967 on the promise of “Renewal” and rebuilding pride in the country and its heritage. The first signs of a philosophy supporting a Torrike-led empire started to be discussed in the public arena. The coalition went from strength to strength throughout the late 60s and 70s, while a new breed of nationalists were building a myth based on the glories of the Skolkan Empire and the need to rebuild it. In the 1980s, new young, ambitious, and ruthless leaders emerged in the parties, and in 1989, the old guard were pushed aside. |

The new leaders pushed Torrike further to the right politically, aiming to build up the military so that the country could “hold its head high in the world” and to establish Torrike’s “rightful place in the region”. Opponents of the regime were increasingly side‐lined and dissenting voices suppressed. | The new leaders pushed Torrike further to the right politically, aiming to build up the military so that the country could “hold its head high in the world” and to establish Torrike’s “rightful place in the region”. Opponents of the regime were increasingly side‐lined and dissenting voices suppressed. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 23: | ||

As the country has become more prosperous, so it has invested in the natural resources of countries outside the region. Having missed out on the oil boom for geographic reasons, Torrike has sought to gain access to other potential areas of interest and is deeply interested in gaining access to the Arctic. When Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire had initially tried to retain northern Norway as this gave it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid‐90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of Northern Norway. The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition. | As the country has become more prosperous, so it has invested in the natural resources of countries outside the region. Having missed out on the oil boom for geographic reasons, Torrike has sought to gain access to other potential areas of interest and is deeply interested in gaining access to the Arctic. When Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire had initially tried to retain northern Norway as this gave it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid‐90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of Northern Norway. The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition. | ||

| − | = | + | == Key Dates, Time Periods, or Events == |

* 1905 – Norway declared independence from the Skolkan Empire | * 1905 – Norway declared independence from the Skolkan Empire | ||

* 1917 – Civil war within the Skolkan Empire. | * 1917 – Civil war within the Skolkan Empire. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 29: | ||

* 1931 – Constitution of Torrike established as the supreme law for the country. | * 1931 – Constitution of Torrike established as the supreme law for the country. | ||

* 1945 – Torrike joined the United Nations | * 1945 – Torrike joined the United Nations | ||

| − | * 1964 | + | * 1964 – European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights incorporated into the Torrikan Constitution. |

| − | * 1990 – | + | * 1990 – Gulf of Bothnia Cooperation Council (GBCC) founded by Torrike and Bothnia. |

* 1992 – Lars Peerson appointed President, a position he still holds. | * 1992 – Lars Peerson appointed President, a position he still holds. | ||

| − | * 1997 | + | * 1997 – GBCC signs an economic framework agreement. |

| − | * 2001 – Arnland joined | + | * 2001 – Arnland joined GBCC. |

| − | * 2001 | + | * 2001 – Torrike and Bothnia signed the Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation. |

| − | * 2004 | + | * 2004 – National Cyber Security Agency (NCSA) established |

| − | * 2005 | + | * 2005 – GBCC Interbank established |

| − | * 2007-08 | + | * 2007-08 – Torikkan defense policy substantially revised. |

| − | = | + | == Routine, Cyclical Key Dates == |

| − | == | + | === Public Education === |

| − | '''Kindergarten/ | + | '''Kindergarten/Preschool''': Three-year program |

| − | '''Primary school''': | + | '''Primary school''': Four‐year foundation stage (Primary 1 to 4) and a two‐year orientation stage (Primary 5 to 6). |

'''Secondary school''': Special and Express are four‐year courses. Normal is a four or five‐year course. | '''Secondary school''': Special and Express are four‐year courses. Normal is a four or five‐year course. | ||

| Line 48: | Line 53: | ||

'''Vocational''': Three-year program. | '''Vocational''': Three-year program. | ||

| − | More details are in the Social Variable. | + | More details are in the [[Social: Torrike|Social Variable]]. |

| − | == | + | === National and Religious Holidays === |

| − | Torrike observes all Christian holidays, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. National holidays include the following: | + | Torrike observes all [[Christian holidays]], New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. National holidays include the following: |

* April 30 – Walpurgis Night (End of the administrative year in the Middle Ages) | * April 30 – Walpurgis Night (End of the administrative year in the Middle Ages) | ||

| Line 58: | Line 63: | ||

* Last Sunday in May – Mother’s Day | * Last Sunday in May – Mother’s Day | ||

* June 06 – National Day | * June 06 – National Day | ||

| − | * Day before Summer Solstice – Midsummer Eve (Midsommarafton) | + | * Day before Summer Solstice – Midsummer Eve (''Midsommarafton'') |

| − | * Summer Solstice – Midsummer Day (Midsommardagen) | + | * Summer Solstice – Midsummer Day (''Midsommardagen'') |

| − | == | + | === Harvest Cycles === |

| − | The growing season lasts 240 days in the south and 100 days in the north. See Physical Variable for more information. | + | The growing season lasts 240 days in the south and 100 days in the north. See [[Physical Environment: Torrike|Physical Environment Variable]] for more information. |

| − | == | + | === Elections === |

Presidential elections are every seven years. Elections for Members of Parliament (MP) are every five years. Local elections are held every year for one third of the total number of seats in the appropriate assembly. More detail can be found in the Political Variable. | Presidential elections are every seven years. Elections for Members of Parliament (MP) are every five years. Local elections are held every year for one third of the total number of seats in the appropriate assembly. More detail can be found in the Political Variable. | ||

| − | == | + | == Military Training == |

| − | Unit and formation level training is run on a two year cycle ending in a major formation level exercise, usually with joint support; while the combined services training cycle is run on a four year basis, culminating in a joint exercise that seeks to test the integration of all the force elements. See Military Variable for more information | + | Unit and formation level training is run on a two year cycle ending in a major formation level exercise, usually with joint support; while the combined services training cycle is run on a four year basis, culminating in a joint exercise that seeks to test the integration of all the force elements. See [[Military: Torrike|Military Variable]] for more information. |

| − | == | + | == Government Planning == |

The Torrikan government fiscal year is the calendar year. | The Torrikan government fiscal year is the calendar year. | ||

| − | = | + | == Cultural Perception of Time == |

Torrike has only one time zone. The country observes Central European Time (CET), or UTC +1, as standard time. When Daylight Saving Time (DST) is in force, Torrikan clocks run on Central European Summer Time (CEST). | Torrike has only one time zone. The country observes Central European Time (CET), or UTC +1, as standard time. When Daylight Saving Time (DST) is in force, Torrikan clocks run on Central European Summer Time (CEST). | ||

| Line 85: | Line 90: | ||

In 1879, the solar time 3 degrees west of the Observatory of Tyr was defined as the national standard time. It was 1 hour and 14 seconds ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), then the world's time standard. To get in line with the global standard, Torrike turned its clocks back by 14 seconds in 1900. The local time was now exactly 1 hour ahead of GMT. The country has been using the same time zone ever since. | In 1879, the solar time 3 degrees west of the Observatory of Tyr was defined as the national standard time. It was 1 hour and 14 seconds ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), then the world's time standard. To get in line with the global standard, Torrike turned its clocks back by 14 seconds in 1900. The local time was now exactly 1 hour ahead of GMT. The country has been using the same time zone ever since. | ||

| − | == | + | == Arctic Perception of Time<ref>https://www.laits.utexas.edu/sami/dieda/anthro/concept-time.htm</ref> == |

| − | The Arctic is an enormous area, sprawling over one sixth of the earth's landmass; twenty‐four time zones and more than 30 million km2. The Arctic is inhabited by some four million people, including more than 30 indigenous peoples of which the Sami are resident in Torrike. | + | The Arctic is an enormous area, sprawling over one sixth of the earth's landmass; twenty‐four time zones and more than 30 million km2. The Arctic is inhabited by some four million people, including more than 30 indigenous peoples of which the Sami are resident in Torrike. Sami knowledge is based on experience in that knowledge was not obtained from a book or taught in classroom, but rather it was accumulated through repeated experiences of particular situations. Sami time is based on the cycles of nature, particularly the yearly cycle of the reindeer. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

Sami concept of seasons are based on the eight reindeer life-cycles and prevailing weather conditions. | Sami concept of seasons are based on the eight reindeer life-cycles and prevailing weather conditions. | ||

| Line 178: | Line 181: | ||

|Yule Month | |Yule Month | ||

|} | |} | ||

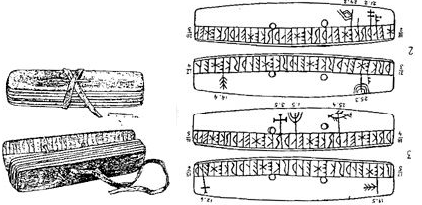

| + | [[File:Sami Wooden Calendar.PNG|thumb|422x422px|'''Sami Wooden Calendar''']] | ||

'''Wooden Calendar'''. To help track these times, the Sami developed a wooden calendar in the mid-1800’s. The wooden calendar is divided in weeks and is easily transportable. Typically fabricated from wood or reindeer antler, this calendar was used to keep track of both natural phenomena and religious occurrences. Written in the runic alphabet, the wooden calendar was a useful tool in helping to preserve the balance between nature and religion as they denoted events in both realms. Crosses denote days of religious significance while fish and leaf sprigs denote various events in nature. By keeping track of time in this way, the Sami could easily refer back to earlier times of the year in order to try to predict when the fishing season would be most bountiful or whether or not spring would arrive early or not. | '''Wooden Calendar'''. To help track these times, the Sami developed a wooden calendar in the mid-1800’s. The wooden calendar is divided in weeks and is easily transportable. Typically fabricated from wood or reindeer antler, this calendar was used to keep track of both natural phenomena and religious occurrences. Written in the runic alphabet, the wooden calendar was a useful tool in helping to preserve the balance between nature and religion as they denoted events in both realms. Crosses denote days of religious significance while fish and leaf sprigs denote various events in nature. By keeping track of time in this way, the Sami could easily refer back to earlier times of the year in order to try to predict when the fishing season would be most bountiful or whether or not spring would arrive early or not. | ||

| − | == | + | == Western Perception of Time == |

Western time is based on scientific calculations and observations. From the sundial to the atomic clock, time relies on such measurements as the rotation of the earth to the number of oscillations of a particular atom. These are finite measurements of time which contrast drastically with the changeable calendar of the Sami. The Western concept of time is not a product of experiential learning but rather a shared careful observation made by a relative minority of the population. Without a watch or clock, most Westerners would be unable to offer what they would consider an accurate estimate of the time. | Western time is based on scientific calculations and observations. From the sundial to the atomic clock, time relies on such measurements as the rotation of the earth to the number of oscillations of a particular atom. These are finite measurements of time which contrast drastically with the changeable calendar of the Sami. The Western concept of time is not a product of experiential learning but rather a shared careful observation made by a relative minority of the population. Without a watch or clock, most Westerners would be unable to offer what they would consider an accurate estimate of the time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Europe Linkbox}} | ||

| + | [[Category:DATE Europe]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Torrike]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Time]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Europe]] | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:35, 19 September 2018

DATE Europe > Torrike > Time: Torrike ←You are here

Time Overview

Torrike represents the heartland and remnant core of a once considerably larger and more powerful political entity, the Skolkan Empire. In the first decades of the 20th Century, the Empire slowly disintegrated as elements declared independence. This process was exacerbated by the First World War (WWI). Although neutral, the Empire did not escape the effects of the conflict and from 1917 was embroiled in a civil war. The independent countries of Arnland in the south and OtsoBothnia in the east were recognized and the Empire was formally declared dissolved in 1920. The remaining territory renamed itself Torrike, with the last Emperor Anders Munch, declared as King. However, Torrike would be a constitutional monarchy and his powers as Head of State were diminished to a purely ceremonial role, while the First Minister amassed political power as Head of the Government. The Parliament (Riksted) moved from being a largely ceremonial establishment filled with appointees, to one which was fully elected and so provided the state with democratic respectability.

Throughout the 1920s, Torrike struggled to come to terms with its diminished size and importance. In seeking a role in the modern world, the political establishment increasingly felt that a monarchy was anachronistic. The advent of the Great Depression and death of King Anders allowed the country to re‐establish itself as a republic, with the extension of the vote to all adult males. Torrike suffered greatly during the Depression years and there were a number of left wing factional attempts to establish a workers’ democracy, which were put down. Although the major political parties (the Unity Party; the Prosperity Party; the Neutrality Party and the Nationalist Party), were right wing and essentially authoritarian, the nascent Fascist Party was ruthlessly suppressed.

Torrike recovered slowly during the 1930s, with stimulus being provided through industrialization and the desire to make the country self‐sufficient in strategic industries. The recovery was helped by increasing demands for Torrikan raw materials; especially iron ore, bauxite and wolframite which were heavily purchased across Europe as the continent rearmed in the run up to the Second World War (WWII). In 1936, women were given the vote. Politically, changes of government produced few changes in policy and the country maintained the character of a center‐right, reasonably moderate, albeit slightly authoritarian, nation. Throughout WWII, Torrike was neutral and formed a Neutrality Pact with Arnland and Framland aimed at keeping the region out of the war. The neutrality was, however, biased towards Germany whose troops were given the right of passage through their territories to Norway after 1940. For most of the war, Torrike enjoyed the benefits of large exports of strategic materials to Germany, but diplomatic channels to the Allies were kept open. As it became increasingly clear that Germany would lose, so the interpretation of neutrality became more favorable to the Allies. Relations with Donovia were more complex. Although Torrike maintained its neutrality in the war between OtsoBothnia and Donovia, there was considerable sympathy for their former countrymen and volunteers and material assistance was sent to OtsoBothnia. Further assistance was provided to OtsoBothnia when it joined the German campaign against Donovia, but a greater distance was maintained from the conflict.

Post WWII, Torrike sought to build on the Neutrality Pact with their neighbors, but both countries resisted Torrikan efforts to influence them. Throughout the 1950s, the moderate Prosperity Party was in power and built the foundations of Torrike’s modern industrial success. By the 1960s, the failure to promote new talent within the Party and complacency led to increasing disillusion with the Party and its politics. A Unity/Nationalist Coalition was elected in 1967 on the promise of “Renewal” and rebuilding pride in the country and its heritage. The first signs of a philosophy supporting a Torrike-led empire started to be discussed in the public arena. The coalition went from strength to strength throughout the late 60s and 70s, while a new breed of nationalists were building a myth based on the glories of the Skolkan Empire and the need to rebuild it. In the 1980s, new young, ambitious, and ruthless leaders emerged in the parties, and in 1989, the old guard were pushed aside.

The new leaders pushed Torrike further to the right politically, aiming to build up the military so that the country could “hold its head high in the world” and to establish Torrike’s “rightful place in the region”. Opponents of the regime were increasingly side‐lined and dissenting voices suppressed.

The collapse of the Warsaw Pact came at an ideal time for the new generation of leaders. The West was distracted and Donovia’s attention was directed inwards. After some maneuvering, Lars Peersson emerged as preeminent among the new generation. Appointed President in 1992, he has driven Torrikan policy and actions since that date towards a very specific view of the region. The basic tenet of his policy was to establish and build Torrike as the regional power through building an economy that would make the country the regional leader.

This ambition has been the foundation for all of Torrike’s actions throughout the last 20 years.

As the country has become more prosperous, so it has invested in the natural resources of countries outside the region. Having missed out on the oil boom for geographic reasons, Torrike has sought to gain access to other potential areas of interest and is deeply interested in gaining access to the Arctic. When Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire had initially tried to retain northern Norway as this gave it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid‐90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of Northern Norway. The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition.

Key Dates, Time Periods, or Events

- 1905 – Norway declared independence from the Skolkan Empire

- 1917 – Civil war within the Skolkan Empire.

- 1920 – Skolkan Empire formally dissolved. Arnland, OtsoBothnia, and Torrike formed as separate countries.

- 1931 – Constitution of Torrike established as the supreme law for the country.

- 1945 – Torrike joined the United Nations

- 1964 – European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights incorporated into the Torrikan Constitution.

- 1990 – Gulf of Bothnia Cooperation Council (GBCC) founded by Torrike and Bothnia.

- 1992 – Lars Peerson appointed President, a position he still holds.

- 1997 – GBCC signs an economic framework agreement.

- 2001 – Arnland joined GBCC.

- 2001 – Torrike and Bothnia signed the Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation.

- 2004 – National Cyber Security Agency (NCSA) established

- 2005 – GBCC Interbank established

- 2007-08 – Torikkan defense policy substantially revised.

Routine, Cyclical Key Dates

Public Education

Kindergarten/Preschool: Three-year program

Primary school: Four‐year foundation stage (Primary 1 to 4) and a two‐year orientation stage (Primary 5 to 6).

Secondary school: Special and Express are four‐year courses. Normal is a four or five‐year course.

Tertiary: Pre‐university and University education.

Vocational: Three-year program.

More details are in the Social Variable.

National and Religious Holidays

Torrike observes all Christian holidays, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. National holidays include the following:

- April 30 – Walpurgis Night (End of the administrative year in the Middle Ages)

- May 01 – Labor Day

- Last Sunday in May – Mother’s Day

- June 06 – National Day

- Day before Summer Solstice – Midsummer Eve (Midsommarafton)

- Summer Solstice – Midsummer Day (Midsommardagen)

Harvest Cycles

The growing season lasts 240 days in the south and 100 days in the north. See Physical Environment Variable for more information.

Elections

Presidential elections are every seven years. Elections for Members of Parliament (MP) are every five years. Local elections are held every year for one third of the total number of seats in the appropriate assembly. More detail can be found in the Political Variable.

Military Training

Unit and formation level training is run on a two year cycle ending in a major formation level exercise, usually with joint support; while the combined services training cycle is run on a four year basis, culminating in a joint exercise that seeks to test the integration of all the force elements. See Military Variable for more information.

Government Planning

The Torrikan government fiscal year is the calendar year.

Cultural Perception of Time

Torrike has only one time zone. The country observes Central European Time (CET), or UTC +1, as standard time. When Daylight Saving Time (DST) is in force, Torrikan clocks run on Central European Summer Time (CEST).

Torrike standardized its time in 1879. Until then, each location had used solar mean time, based on its longitude.

In 1879, the solar time 3 degrees west of the Observatory of Tyr was defined as the national standard time. It was 1 hour and 14 seconds ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), then the world's time standard. To get in line with the global standard, Torrike turned its clocks back by 14 seconds in 1900. The local time was now exactly 1 hour ahead of GMT. The country has been using the same time zone ever since.

Arctic Perception of Time[1]

The Arctic is an enormous area, sprawling over one sixth of the earth's landmass; twenty‐four time zones and more than 30 million km2. The Arctic is inhabited by some four million people, including more than 30 indigenous peoples of which the Sami are resident in Torrike. Sami knowledge is based on experience in that knowledge was not obtained from a book or taught in classroom, but rather it was accumulated through repeated experiences of particular situations. Sami time is based on the cycles of nature, particularly the yearly cycle of the reindeer.

Sami concept of seasons are based on the eight reindeer life-cycles and prevailing weather conditions.

| Season | Explanation |

| Spring-Winter | The herd begins the migration from the forests to the calving grounds in the mountains. |

| Spring | The temperature increases and the snow begins to melt. Reindeer calves are born. |

| Pre-Summer | The reindeer graze and the Sami have some time to rest and prepare for the earmarking of the calves. |

| Summer | Much of this season is bathed in twenty-four hour per day sunlight. During this time, earmarking takes place to denote ownership. |

| Pre-Autumn | The Sami begin to prepare for the harsh winter by choosing the bull reindeer destined for slaughter. |

| Autumn | This is the season of rut. The reindeer mate prior to their return to the winter-grounds. |

| Pre-Winter | The herders lead the reindeer out of the mountains to the lowland bogs. |

| Winter | Under a cover of twenty-four hour per day darkness, the Sami move the reindeer to the forest, the last place to find enough food to support the herd. |

The Sami divide their year into 12 months like the Western calendar. However, these are not set by a specific number of days. They are based on natural phenomena.

| Western | Sami | Meaning |

| January | Ođđajagemánnu | New Year Month |

| February | Guovvamánnu | Unknown |

| March | Njukčamánnu | Swan Month |

| April | Cuoŋománnu | Snow Crust Month |

| May | Miessemánnu | Reindeer Calf Month |

| June | Geassemánnu | Summer Month |

| July | Suiodnemánnu | Hay Month |

| August | Borgemánnu | Molt Month |

| September | Čakčamánnu | Fall Month |

| October | Golggotmánnu | Rut Month |

| November | Skábmamánnu | Dark-Period Month |

| December | Juovlamánnu | Yule Month |

Wooden Calendar. To help track these times, the Sami developed a wooden calendar in the mid-1800’s. The wooden calendar is divided in weeks and is easily transportable. Typically fabricated from wood or reindeer antler, this calendar was used to keep track of both natural phenomena and religious occurrences. Written in the runic alphabet, the wooden calendar was a useful tool in helping to preserve the balance between nature and religion as they denoted events in both realms. Crosses denote days of religious significance while fish and leaf sprigs denote various events in nature. By keeping track of time in this way, the Sami could easily refer back to earlier times of the year in order to try to predict when the fishing season would be most bountiful or whether or not spring would arrive early or not.

Western Perception of Time

Western time is based on scientific calculations and observations. From the sundial to the atomic clock, time relies on such measurements as the rotation of the earth to the number of oscillations of a particular atom. These are finite measurements of time which contrast drastically with the changeable calendar of the Sami. The Western concept of time is not a product of experiential learning but rather a shared careful observation made by a relative minority of the population. Without a watch or clock, most Westerners would be unable to offer what they would consider an accurate estimate of the time.

| DATE Europe Quick Links . | |

|---|---|

| Arnland | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Bothnia | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Donovia-West | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Framland | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Otso | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Pirtuni | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Torrike | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Other | Non-State Threat Actors and Conditions • DATE Map References • Using the DATE |