Difference between revisions of "Political: Torrike"

m (→Legislative) (Tag: Visual edit) |

(→Executive: Changed date of Perrsson's first election to 1993.) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

=== Executive === | === Executive === | ||

| − | The President is the Head of State, who is elected on the basis of universal suffrage. The President need not be a member of a political party and any full citizen of Torrike may be nominated for election. A President may be dismissed by national referendum before expiration of his term of office. The referendum must be held if the Parliament so desires. If the referendum result produces a majority against dismissing the President, then the Parliament will subsequently be dissolved and new elections will be held. The current President, Mr. Lars Peersson has been in office since | + | The President is the Head of State, who is elected on the basis of universal suffrage. The President need not be a member of a political party and any full citizen of Torrike may be nominated for election. A President may be dismissed by national referendum before expiration of his term of office. The referendum must be held if the Parliament so desires. If the referendum result produces a majority against dismissing the President, then the Parliament will subsequently be dissolved and new elections will be held. The current President, Mr. Lars Peersson has been in office since 1993. |

The Government comprises a Cabinet of up to 15 full members, led by a Prime Minister who is appointed by the President. It is not unknown for a Prime Minister to be used as a scapegoat for unpopular decisions or events, and replaced, allowing the President to escape criticism. The office of President has considerable powers, the major ones of which are listed below: | The Government comprises a Cabinet of up to 15 full members, led by a Prime Minister who is appointed by the President. It is not unknown for a Prime Minister to be used as a scapegoat for unpopular decisions or events, and replaced, allowing the President to escape criticism. The office of President has considerable powers, the major ones of which are listed below: | ||

Revision as of 20:49, 17 July 2018

Contents

- 1 Political Overview

- 2 Historical Summary

- 3 Political System

- 4 Central Structure

- 5 Influential Individuals

- 6 Regional Administration

- 7 Domestic Policies

- 8 Government Effectiveness and Legitimacy

- 9 International Relationships

- 10 Political Entities

Political Overview

Torrike has an area of 347,400 square kilometers (km²), bordering Norway to the north and west, Donovia, Otso and Bothnia to the northeast, Framland and the Baltic Sea to the east, Arnland to the south and the Skagerrak to the south west. Its capital is Tyr.

Politics: Torrike politics is dominated by the Torrike Unity Party (TUP) which has been Torrike’s ruling political party since 1967, either alone, or in coalition with the Torrikan Nationalist Party (TNP). There are 10 other recognized political parties, but only the TUP and the TNP are significant.

Government: Parliamentary Democracy.

Foreign Relations: Torrike has full diplomatic relations with all United Nations (UN) member states.

Legal System: Mixed Law

International Agreements: Founder member of, and active participant in, the Skolkan Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Skolkan Economic Community (SEC), and the UN. It is a signatory to the Helsinki Accords, and the Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction Agreement.

Historical Summary

Torrike represents the heartland and remnant core of a once considerably larger and more powerful political entity, the Skolkan Empire. In the first decades of the 20th Century, the Empire slowly disintegrated as elements declared independence. This process was exacerbated by the First World War. Although neutral, the Empire did not escape the effects of the conflict and from 1917 was embroiled in a civil war. The independent countries of Arnland in the south and OtsoBothnia in the east were recognized and the Empire was formally declared dissolved in 1920. The remaining territory renamed itself Torrike, with the last Emperor Anders Munch, declared as King. However, Torrike would be a constitutional monarchy and his powers as Head of State were diminished to a purely ceremonial role, while the First Minister amassed political power as Head of the Government. The Riksted, or Parliament, moved from being a largely ceremonial establishment filled with appointees, to one which was fully elected and so provided the state with democratic respectability.

Throughout the 1920s, Torrike struggled to come to terms with its diminished size and importance. In seeking a role in the modern world, the political establishment increasingly felt that a monarchy was anachronistic. The advent of the Great Depression and death of King Anders allowed the country to re‐establish itself as a republic, with the extension of the vote to all adult males. Torrike suffered greatly during the Depression years and there were a number of left wing factional attempts to establish a workers’ democracy, which were put down. Although the major political parties (the Unity Party; the Prosperity Party; the Neutrality Party and the Nationalist Party), were right wing and essentially authoritarian, the nascent Fascist Party was ruthlessly suppressed.

Torrike recovered slowly during the 1930s, with stimulus being provided through industrialization and the desire to make the country self‐sufficient in strategic industries. The recovery was helped by increasing demands for Torrikan raw materials; especially iron ore, bauxite and wolframite which were heavily purchased across Europe as the continent rearmed in the run up to WWII. In 1936, women were given the vote. Politically, changes of government produced few changes in policy and the country maintained the character of a center‐right, reasonably moderate, albeit slightly authoritarian, nation. Throughout WWII, Torrike was neutral and formed a Neutrality Pact with Arnland and Framland aimed at keeping the region out of the war. The neutrality was, however, biased towards Germany whose troops were given the right of passage through their territories to Norway after 1940. For most of the war, Torrike enjoyed the benefits of large exports of strategic materials to Germany, but diplomatic channels to the Allies were kept open. As it became increasingly clear that Germany would lose, so the interpretation of neutrality became more favorable to the Allies. Relations with Donovia were more complex. Although Torrike maintained its neutrality in the war between OtsoBothnia and Donovia, there was considerable sympathy for their former countrymen and volunteers and material assistance was sent to OtsoBothnia. Further assistance was provided to OtsoBothnia when it joined the German campaign against Donovia, but a greater distance was maintained from the conflict.

Post WWII, Torrike sought to build on the Neutrality Pact with their neighbors, but both countries resisted Torrikan efforts to influence them. Throughout the 1950s, the moderate Prosperity Party was in power and built the foundations of Torrike’s modern industrial success. By the 1960s the failure to promote new talent within the Party and complacency led to increasing disillusion with the Party and its politics. A Unity/Nationalist Coalition was elected in 1967 on the promise of “Renewal” and rebuilding pride in the country and its heritage. The first signs of the Greater Skolkan philosophy started to be discussed in the public arena. The coalition went from strength to strength throughout the late 60s and 70s, while a new breed of nationalists were building a myth based on the glories of the Skolkan Empire and the need to rebuild it. In the 1980s, new young, ambitious, and ruthless leaders emerged in the parties, and in 1989, the old guard were pushed aside.

The new leaders pushed Torrike further to the right politically, aiming to build up the military so that the country could “hold its head high in the world” and to establish Torrike’s “rightful place in the region”. Opponents of the regime were increasingly side‐lined and dissenting voices suppressed.

The collapse of the Warsaw Pact came at an ideal time for the new generation of leaders. The West was distracted and Donovia’s attention was directed inwards. After some maneuvering, Lars Peersson emerged as preeminent among the new generation. Appointed President in 1992, directed Torrikan policy and actions, since that date, towards a very specific view of the region. The basic tenet of his policy was to establish and build Torrike as the regional power through building an economy that would make the country the regional leader.

This ambition has been the foundation for all of Torrike’s actions throughout the last 20 years. A number of highly successful world class businesses developed, many of which, electronics, software, heavy vehicles, etc. have dual military/civilian applications in addition to a large and efficient arms industry. As the country has become more prosperous, it invested in the exploitation of natural resources of countries outside the region. Having missed out on the oil boom for geographic reasons, Torrike has sought to gain access to other potential areas of interest and is deeply interested in gaining access to the Arctic. When Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire initially tried to retain northern Norway as this gave it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid‐90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of Northern Norway. The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition. Although bountifully supplied with hydro‐electricity, Torrike has a nuclear plant in Forsmark and owns the Ringhals plant in Arnland to ensure the energy security of the country. There are rumors of a secret military nuclear program, but these have never been verified.

Political System

Torrike’s formal political system is democratic, based on universal suffrage, with both the Head of State (President) and the governing body, Parliament, being subject to periodic election. The President is elected separately from the Parliament and at different time intervals (seven years and five years respectively). However, Torrike’s power structure is highly centralized, characterized by a top‐down style. It features appointment rather than election to most offices and the control of patronage ultimately rests with the President. The Head of State of the Republic of Torrike is the President, Mr. Lars Peersson was re-elected September 2014 and is serving his fourth consecutive seven-year term in office. The Prime Minister, appointed by the President, is Mr. Olof Olofson, who was sworn in on 12 August 2014.

The combination of the centralized power structure with the pursuit of policies that accord with the Torrikan electorate’s view of their nation and its role in the world has allowed Peersson to drive the country with a fairly light touch. The economic prosperity that has accompanied these policies has reinforced his position, with credit for successes going to Peersson, while other politicians take the blame for any setbacks. There are both formal and informal mechanisms for dealing with political dissent and these can be used ruthlessly when the occasion arises. However, for the most part Torrikans are extremely content with their system and their politics and those who oppose current policies have little traction.

The Government of Torrike consists of a Cabinet led by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President normally from the majority party within the Parliament. The President has considerable scope on who he appoints. Nominally, the leader of the political party that secures the most seats in Parliament will be appointed as PM. However, the President is not obliged to select this individual and has on occasions chosen another. The President’s control of patronage makes this a viable option. The President and the Government together constitute the Executive Branch of the country. Although nominally a member of the Torrikan Unity Party (TUP), the President does not obviously favor ‘his’ party over the Torrikan Nationalist Party (TNP) and successfully presents himself as working with all parties towards the good of the nation. However, his control of patronage and other levers ensures that the final authority rests with the President.

The Constitution

The current Constitution of Torrike dates back to 1931 and is the supreme law of the Republic of Torrike. It lays down the fundamental principles and framework for the Executive, the Legislative and the Judiciary and their roles within the State. Additionally, it guarantees the fundamental liberties of Torrike citizens: liberty of the person; prohibition of slavery and forced labor; protection against retrospective criminal laws and repeated trials; equal protection under the law; prohibition of banishment and freedom of movement; freedom of speech, assembly and association; freedom of religion; and rights in respect of education. The major amendments to the Constitution since its original inception have increased the power of the President, who among other powers has the right to veto any legislation made by Parliament. The Constitution cannot be amended without the approval of more than two‐thirds of the members of the parliament on the second and third readings.

Central Structure

The Torrikan political structure is designed to ensure that the people have the maximum opportunity to exercise democratic control over the country and its governance. There are, in effect, three democratically elected levels, with the President, Parliament and regional authorities all subject to periodic elections. On the regional level there are the counties and on the lowest level there are municipalities. Power and political direction on national issues flows down from the top. The state level enacts laws and regulations that in turn give the over‐arching directions for counties/regions and municipalities. While local issues are debated and resolved locally, the overarching structure and policies within which the issue must be resolved are set by the Government.

Branches of Government

Executive

The President is the Head of State, who is elected on the basis of universal suffrage. The President need not be a member of a political party and any full citizen of Torrike may be nominated for election. A President may be dismissed by national referendum before expiration of his term of office. The referendum must be held if the Parliament so desires. If the referendum result produces a majority against dismissing the President, then the Parliament will subsequently be dissolved and new elections will be held. The current President, Mr. Lars Peersson has been in office since 1993.

The Government comprises a Cabinet of up to 15 full members, led by a Prime Minister who is appointed by the President. It is not unknown for a Prime Minister to be used as a scapegoat for unpopular decisions or events, and replaced, allowing the President to escape criticism. The office of President has considerable powers, the major ones of which are listed below:

- Head of State

- Appoints (and can dismiss) the Prime Minister

- Appoints (and can also nominate) major government Ministers

- Authorizes all laws

- Has the right of veto over laws proposed by the Riksted

- Commander in Chief of Armed Forces

- Granted immunity from prosecution for life

- Has the power to dismiss the government and dissolve the Riksted

- Has the power to grant legal pardons on the advice of the Cabinet

- Appoints and receives ambassadors

The PM will usually choose his Ministers from elected MPs to form the Cabinet; these appointments are also subject to Presidential approval. Ministers need not necessarily be Members of Parliament (MP). Torrike has a long history of appointing especially talented individuals to Ministries when it is felt that their expertise would be useful to the Government. This has particularly been the case on industrial and social matters.

In addition to the formal Ministries, there may be up to two Ministers‐Without‐Portfolio in the Cabinet to provide additional support. Each Minister may also have the assistance of a number of Junior Ministers, but these individuals do not count as full, or voting, members of the Cabinet.

The current structure of the Cabinet is shown below (full members only):

- Mr. Olof Oloffson: The Prime Minister

- Mr. Quirin Rylander: Minister of Finance

- Dr. Neo Hammar: Minister of the Interior

- Mr. Donatus Amdahl: Minister of Defence

- Mrs. Mean Frost: Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Mr. Elton Gran : Minister of National Development

- Ms. Vega Sellin: Minister of Trade and Industry

- Prof. Veronique Strutz: Minister of Justice

- Dr. Leopold Thulin: Minister of Education

- Dr. Cecylja Eld: Minister of Health

- Mr. Juvan Buske: Minister of Transport

- Mrs. Gurly Orn: Minister of Manpower

- Ms.Dorit Lytle: Minister of the Environment

- Mr. Kit Hus : Minister of Information and Communications

- Dr. Hulda Hultquist: Minister of the Arts

- Mr. Tubbe Loving: Minister of Community Development, Youth and Sport

Legislative

The unicameral Riksted (parliament) is the Legislative body of Torrike. Under the Constitution, it is charged with three major functions: debating and approving laws drafted by the Government, overseeing the proper management of the State’s finances and holding the Government and its Ministers to account for their actions in governing the State. Members of the Riksted (MR) are voted in at General Elections, and the ‘life’ of each Parliament is five years from the date of its first sitting after a General Election. New elections have to be held within three months of the dissolution of the Riksted. It has its own governance structure, and the ability to speak with one voice.

Members of the Riksted (MRs) are elected both to represent their community and to act as a bridge between the people and the government by ensuring that concerns of the people are heard. When in session, the Speaker chairs the sittings of the legislative body and enforces the rules prescribed in the Riksted Standing Orders to ensure the orderly conduct of the legislative business. The Speaker also acts as the Riksted's representative when there are issues between the assembly and the Government. The Speaker receives support from the Riksted Secretariat which enforces parliamentary procedures and practices, the organization of its business, and the undertakings of its committees.

Legislation is normally drafted by the Government and then submitted to Parliament for debate and amendment as necessary. However, the Riksted can also propose legislation which the Government will convert into a draft bill, for debate. Additionally, members of the public can also propose legislation through a ‘Popular Motion’; providing it is supported by at least 100,000 signatures from qualified members of the electorate, then this motion must be submitted for debate and resolution. Any law enacted by the Riksted may be made the subject of a national referendum before it is placed on record if the a majority votes in favor of sending it to the public for a final vote.

Legislation has to be approved by a majority of the Riksted, but does not become law until formally signed by the President. The net result of this structure is a distinct political culture that is authoritarian, pragmatic, rational and legalistic and firmly under the control of the TUP and above all, the President.

Judicial

Torrike is one of the inheritors of the Skolkan legal system and as such its judicial structure shares many features with Arnland and Framland. At its simplest, the judiciary consists of two levels of court, the Supreme Court and subordinate courts. However, this division offers a clarity that the reality does not quite match. The judicial system derives its authority from the Constitution and all verdicts and findings are proclaimed and published in the name of the Republic of Torrike. Judicial independence is guaranteed by the Constitution.

Both judicial authority and the rights of the citizens of Torrike flow from the Constitution which incorporated the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights in 1964. All citizens have the right to a speedy and fair trial and the freedom from inhumane or humiliating punishment. The judicial system of Torrike is designed to ensure that any case against a citizen is heard by an appropriate court or authority without undue delay and consists of:

- Independent courts of law and administrative courts

- The State Prosecution Service

- The enforcement authorities, who are responsible for ensuring that judgements are enacted

- The prison and probation services who are responsible for ensuring custodial sentences are carried out

- The Bar Association who are responsible for the maintenance of the quality of legal practitioners

Legal System. Torrike’s legal system is officially designated a mixed system, sometimes referred to as pluralistic law. Mixed law consists of elements of some or all of the other main types of legal systems ‐ civil, common, and customary. The Skolkan legal system which was similar to most western European law systems, is the basic foundation of Torrikan law, but there are other influences. Major areas of law, particularly administrative law, contract law, equity and trust law, property law and tort–law are largely judge‐made. However, other areas of law, such as criminal law, company law and family law, are almost completely statutory in nature. Additionally, Torrikan judges continue to refer to Skolkan case law where the issues pertain to a traditional common‐law area of law, or involve the interpretation of Torrikan statutes based on Skolkan enactments or statutes applicable in Torrike.

Certain Torrike statutes are not based on Skolkan enactments but on legislation from other jurisdictions. In such situations, court decisions from those jurisdictions from which the original legislation derived are often examined. Interpretation of the Constitution is, however, always based on Torrikan and Skolkan principles.

The judiciary is independent from the executive at every level of jurisdiction and judges have full independence in the exercise of their duties. However, the Chief Justice, and all Judges of Appeal, Judicial Commissioners and High Court Judges are appointed by the President from a list of candidates recommended by the PM.

The Courts. The Torrikan court system has two tiers, the Supreme Court and Subordinate Courts. The Supreme Court acts as a final court of appeal for both civil and criminal proceedings, while a range of Subordinate Courts, including District, Magistrate, Community and Family Courts all have their own specialized areas of responsibility. The judiciary is separate from the executive at every level of jurisdiction and judges are not merely independent, but in theory, they may be neither dismissed nor transferred. In practice, judges have been removed from office when the President or political elite have been challenged.

The Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has two elements, the High Court and The Court of Appeal. The High Court hears important or major civil and criminal cases, while as its name suggests, the Court of Appeal exercises appellate criminal and civil jurisdiction. The Court of Appeal does not only consider cases arising from the High Court, but also acts as the final Court of Appeal for the subordinate courts.

Subordinate Courts. There is a range of subordinate courts, each operating in a clearly defined jurisdiction. The most significant ones are the District Courts and Magistrates Courts which hear both civil and criminal cases. Most specialized courts include:

- The Coroner’s Court which holds inquiries to ascertain the cause of death and attribute blame where death has come suddenly or as a result of violence.

- The Community Court which deals with offenders aged between 16 and 18, domestic violence cases and offenders with mental disabilities.

- The Family Court which deals with various family related matters including divorce cases and maintenance orders.

Many of the subordinate courts have traditionally been staffed by volunteers. In 2006, the subordinate courts initiated a pilot scheme to appoint specialist judges to the Bench. These judges will come from the legal profession and academia and the scheme is aimed at bringing additional expertise to the subordinate courts as well as giving practitioners and academics an insight to the workings of the Torrikan judiciary.

Influential Individuals

Outside of the normal political power structure, there are a number of individuals who wield considerable influence within Torrike, either because of their role within a region, or because of their contribution to the formation of opinion within the country. Some are influential because of their wealth, others because of their contribution to the intellectual life of the nation and yet others simply because their ability to generate publicity gives their views wide exposure.

Regional Administration

Torrike is divided into 14 counties and 289 municipalities. Local government is administered by county councils and municipalities consisting of at least 20 members, or representatives. Each council has an executive board with various committees. The County Councils are the highest regional‐level decision making body and exercise the county’s legislative powers. They meet regularly and their meetings are accessible to the public. Their tasks include deciding on county budgets and the level of local taxes, in addition to managing the administration of the county. The members of the County Council are elected by all residents of the county eligible to vote. The County Councils manage their areas with a large degree of independence from the central government, which gives them the opportunity to make decisions based on their particular regional requirements and economic situation.

Each County, however, also has a County Governor who is appointed by the national Government and who is responsible for ensuring the local administration is run in accordance with the Government’s intentions. All legislation passed by the County Council must be certified, countersigned and published by the Governor before it can take effect.

The main source of income for the counties is the so‐called county tax which is levied on the inhabitants of the county. Generally, this tax finances about 70% of the public activities undertaken in the county. The State of Torrike decides what the counties can levy tax on, but the level of taxation, and how this income will be used/distributed is decided by the counties/regions themselves. In addition, counties also receive financial support from the State. Some of this support is earmarked for certain areas based on directions from the State; however, other financial contributions are more general in nature and can therefore be used by the counties in accordance with their own dispositions. Another source of revenue for the counties is that generated from services they provide to the general public. Their main responsibilities include the management of schools up to high school‐ level, special‐needs schools, adult education, social services for individuals and families, cultural services, care for the elderly and handicapped, primary health care, public transportation services, rescue services, crises management, and regional development.

Domestic Policies

Torrike is a sophisticated and well-ordered country with a highly organized and effective administrative structure. By most European standards, the country would be regarded as over‐regulated operating within a fairly rigid set of social norms, backed up rigorously by laws specifying acceptable behavior and standards. Torrike has a universal health care system where the government ensures affordability, largely through compulsory savings and price control. The education system is largely State funded, although there is some private provision; private educational facilities are regulated by the Government. Meritocracy is a fundamental principle in the educational process and overall the system is not only effective, but highly regarded in other countries. The crime rate is low and the system of policing effective. A compulsory social savings scheme, the Greater Torrike Visionary Fund (GTVF), provides financial security for old age and can be drawn on for housing, medical and educational costs before retirement age. The overall civil administration scheme is comprehensive and well run; it is also highly regulated and the legal process is used to channel behavior and attitudes in a specific direction.

The major aspects of government are administered by the Civil Service which employs some 63,000 personnel covering the full range of responsibilities. In keeping with the national philosophy of control and regulation, the Civil Service is overseen by the Public Service Commission (PSC) which is the custodian of the integrity and values of the Civil Service. The PSC is tasked to appoint, confirm, promote, transfer, dismiss and exercise disciplinary control over public servants. Its vital role is to safeguard integrity, impartiality and meritocracy in the Civil Service. Thus, for the most part, the promotion or placement of key government officials is based on qualifications, experience and merit.

For all the light touch evinced by the establishment, Torrike is a nation that is clearly guided by an authoritarian hand. For the most part, the aims of the President coincide with the majority of the population and so there has been little dissent.

In theory, the Riksted is fully independent of the Government.

Torrike’s official position is that all aspects of the media whether commercial or private are entitled to publish any views, within reason. Official censorship is limited to material containing excessive violence, extreme sexual content or extremist political, racist or religious messages.

The domestic policy of Torrike is driven by a consensus that a successful and modern society should be meritocratic, healthy, well-educated and content. A modern economy requires enthusiastic workers who are given the opportunity to exercise their talents to the limits of their ability, guided by humane and informed social and industrial policies. The future for the developed world lies at the higher end of the technological spectrum, although extractive industries and agriculture will remain important. This combined with Torrikans natural entrepreneurial flair will allow Torrike to build and maintain a successful economy in an increasingly competitive world and allow it to hold its head high in the world. This approach can only succeed where government is open and transparent and clearly working for the betterment of the nation and its people. Finally, people from all walks of life should be encouraged to work with each other and learn to value and practice cooperation and communication and military service is an essential means to this end.

The entire civil governance structure is directed at the achievement and furtherance of this consensus, with the understood, but never explicit, aim of establishing Torrike as the pre‐eminent nation in the region. The level of consensus on this vision allows for an open style of governance that enables citizens to check that all activities are contributing to the achievement of that aim. Considerable attention and effort is focused on education, the health system and the social safety net for those unfortunate enough to be unemployed or unemployable. It also excuses the somewhat prescriptive approach to social and other issues. The Torrikan approach is underpinned by an official information strategy that sets out the State’s aims within the context of a free and open press.

On the economic front, the State’s policy is directed towards the nurturing of successful and profitable companies, with a special emphasis on high technology industries and arms production. The overall policy is one of guiding industry in only the broadest terms and leaving industrialists to achieve the stated goals in the most effective manner possible. There is a sound appreciation of the fact that the internal market is not large enough to support its ambitions and that a light touch is more effective than a restrictive one and privately owned firms account for 90% of industrial output. There are, however, strict limits on foreign ownership of Torrikan companies. The broad policy will continue to support a free market approach with structural regulations in place.

Like every other aspect of Peersson’s approach, the content of domestic policy is driven by his idée fixe; the reintegration of the region’s nations into a reinvigorated Skolkan under Torrikan leadership. To achieve this he needs a strong military which in turn is supported by a robust economy which in turn requires a contented and supportive workforce. The fact that this driver is never stated, should not obscure its centrality.

Administration. The actual administration of the country and execution of the various policies adopted by the Government is heavily top down. Government sets the broad policy goals and guidelines on the acceptable norms and the relevant Ministry is responsible for ensuring that they are put into effect. Local administration is the responsibility of the County Councils, who have a fair degree of leeway in their actions, but the Government appointed County Governor ensures that the Council conforms to the broad policy. The Civil Service is the glue that holds it all together.

The employment structure in the Civil Service is stratified into Schemes of Service, each of which has its distinct job characteristics or functional areas. There are minimum educational requirements for entry into each scheme to ensure the quality and caliber of recruits into the Service. Officers in the same scheme share the same salary, benefits and progression structure. Employment as a Civil Servant is a source of pride and prestige in Torrike. The government has consciously followed a rigorous policy to cultivate and nurture the civil service, to ensure that it has the best talents to drive the country forward. This policy is most evident in four ways:

Firstly, the country’s service delivery needs and emerging global trends are continuously analysed, and the Civil Service is realigned accordingly. To achieve this, the Government makes considerable use of the knowledge available from the business, industrial and educational sectors.

Secondly, the government uses the PSC to identify, nurture and groom promising young talents for Civil Service leadership positions, this includes providing scholarships to local and foreign universities, and continuing development programs.

Thirdly, public servants in Torrike receive very competitive salaries, rivalling even the private sector. This, complemented by a merit‐ based personnel assessment system supports civil service performance management and provides incentives, including promotion and performance bonuses, for good performers.

Lastly, in addition to providing a relatively high salary structure for the civil service, the government has exhibited strong political will to combat corruption through the introduction of stringent administrative and legal measures, empowering the independent Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) to prosecute corrupt officials, and promote ethical leadership. Importantly, successful prosecutions of cases against public officials, whose cases are also displayed publicly in the CPIB website, have also bolstered public support to the government’s anticorruption drive. With a Corruptions Perception Index (CPI) score of 6.3 (where 10 is the least corrupt), Torrike is clearly not especially corrupt, but there is room for improvement.

Business Development. In the furtherance of its economic aims, Torrike does not just encourage business, but actively supports it with the Ministry of National Development charged with stimulating the growth, expansion and development of Torrike’s economy. Additionally, there is a government owned investment company, Torrikan Investment Holdings (TIH). With an international staff of 380 people, TIH manages a portfolio of about USD142 billion, focused primarily in Europe. It is an active shareholder and investor in financial services, telecommunications & media, technology, transportation, industrials, life‐sciences, consumer, real estate, energy and resources. The intent is to build up national stakes in sectors of industry that will prove useful to Torrike’s own businesses and economy and in so doing, provide Torrikan companies with access to additional markets and technology. The State still owns substantial stakes in certain areas of business, not least a 35% holding in Telecom and 12% of Econombank. However, these are being slowly privatized, as are other government holdings. The State monopoly of pharmaceuticals will be broken in the near future.

Checks and Balances. As part of the system of checks and balances, public authorities´ financial dealings, legislation and administration are subject to scrutiny by the Central Auditing Office (CAO). The CAO’s functions include monitoring the activities of the national, regional (Counties), municipal and other public bodies and compiling the annual National Auditors’ Report which is submitted to Parliament. The CAO is fully independent of both central Government and the county Councils, is subject only to the provisions of the law and is nominally directly answerable only to Parliament. However, the Chairman is directly appointed by the President.

There are two further levels of checks and balances on public bodies:

- Parliament is empowered to monitor the activities of the Government, to question members of the Government on all issues pertaining to executive action, to require all relevant information, and to voice their wishes on the implementation of executive powers in the form of parliamentary resolutions.

- The Torrikan Ombudsman Board (TOB), established in 1983, is responsible for investigation of complaints from any person who against a public administrative authority. When dealing with such complaints, the Ombudsman has the unconditional right to inspect all relevant documentation. On completion of the investigation, the Ombudsman may recommend to the public authority concerned that the subject of the complaint be rectified. The Ombudsman Board is an independent institution answerable only to the Parliament, to which the TOB submits an annual report.

Law Enforcement

Law enforcement within Torrike falls firmly under the remit of the Ministry of Justice. There are two parallel structures under the Ministry.

The Chancellor. The Chancellor of Justice is responsible for the supervision of public lawyers and officials in the justice system and in particular the enforcement of standards within the official arm of the legal profession. His responsibilities include the investigation of professional misconduct by public officials. The office also oversees the Torrikan Prosecution Authority (TPA) and is charged with ensuring that public prosecutions are executed expeditiously and to the expected standard.

The TPA, headed up by the Prosecutor General, leads and supervises criminal investigations and prepares and presents such cases to the courts.

The Police Service. The Torrikan National Police Board (TNPB) is the central administrative and supervisory authority of the police service. As such it is responsible for all aspects of administration of the Torrikan Police Service, including policing methods and the development of new working methods, professional standards and personnel management. The TNPB provides national technical support for the police service and manages the National Laboratory of Forensic Science. The TNPB directly controls and runs the National Police Academy and so oversees all aspects of training for the service. The day to day management of the Police Service is handled regionally by the County Police Authority, which is headed by a County Police Commissioner. Oversight of the TPNB is provided directly by the Ministry of Justice, while in each of the 14 counties of Torrike, oversight of the Police is provided by the County Police Board, consisting of local politicians and a County Police Commissioner. The Commissioners and the members of the board are all appointed by the Government of Torrike. The head of the TNPB, the National Police Commissioner, is also appointed by the government. The current Commissioner is Mr. Bengt Svenson.

The Police Service covers the full gamut of specializations and services expected by a modern police force. In addition to the usual range of departments, most of which are run on a regional basis, the following departments operate on a national basis:

- The National Criminal Investigations Department (NCID) is specially charged with all aspects of the policing of Organized Crime (OC).

- The National Task Force (NTF) is a paramilitary unit tasked with counter terrorist measures. The NTF incorporates the national hostage release unit.

- A national SWAT emergency response team.

- The National Economic Crimes Bureau, which is a multi disciplinary agency.

- The Police Air Service which operates a small number of helicopters for observation and search purposes. While this is a national service, the aircraft are dispersed throughout the country at Tyr, Gothenburg, Oestersund and Kiruna.

The Torrikan Police Service has a total of some estimated 43,000 employees of whom 39% are women. There are 30,000 police officers of whom 25% are female and 12,500 civilian staff, 70% of whom are women. Although the Police are the organization with prime responsibility for law enforcement, under certain circumstances other government agencies can be tasked with law enforcement, including investigations, arrests, or the enforcement of judgments. However, as is the case in the USA, Torrikan law has provisions similar to the Posse Comitatus Act limiting the use of the military to perform the tasks of law enforcement agencies in time of peace. This rule has recently come under review; in light of the upsurge of terrorist activity following the 9/11 attacks, the bombings in Bali, Madrid, and London, and the expansion of terrorist activity in Arnland. The heightened terrorist threats caused a proposal to surface from the Rikstead to allow the military to aid the police in certain situations.

Emergency Services

The National Civil Emergency Service (NCES) is controlled by the Ministry of Interior (MOI) and is responsible for peace time emergency and contingency planning for Torrike. Its tasks include coordination of the various branches of the national emergency services and providing professional expertise to the county authorities’ emergency planning teams. The Service is tasked with:

- Planning and managing responses to a nuclear accident • at any of Torrike’s reactors.

- Planning and managing responses to oil spills or the release of toxic waste.

- Maintaining SA on developments in civil emergency and catastrophe response techniques world‐wide and applying the relevant lessons to Torrike.

- Sponsoring research into rescue techniques and equipment and developing the results for practical applications.

- Regulating the transportation of dangerous goods and managing the relevant supervisory authorities.

- Managing the training of all personnel in the fire and rescue services nationwide.

The NCES has recently acquired responsibility for planning the responses to epidemics, natural disasters and chemical emergencies. The service is for the most part is not responsible for the execution of the plans, which lies with the local rescue agencies, law enforcement agencies or other branches of the County. The service is based in Tyr, but has a number of regional offices throughout Torrike.

Fire Services. Firefighting services are provided by a mix of professional and volunteer firemen. Units in the larger towns and cities tend to be fully professional while those in rural areas are largely manned by volunteers. A small number of units are jointly manned by both. In construct and function, the fire‐fighters are modelled on the French Sapeurs‐Pompiers and have responsibility for responding to all accidents and incidents, not just fires. The protection of life is their primary aim, followed by protecting property and the environment, limiting damage and consequences. In large fires (particularly forest fires) the rescue services can also call on the assistance of the Torrikan military. There are approximately 5,000 full time firemen and over 12,000 voluntary firefighters on call.

Coast Guard and Rescue Services. The Torrikan Coast Guard is a small but effective organization that is responsible for rescue services within Torrike’s inshore waters. The Coast Guard has a total of only 500 personnel spread across 12 stations, including one on Lake Vänern, and two operations centers. Long distance operations and SAR fall firmly into the remit of the military, who guard their control jealously. The Coast Guard has an excellent reputation as a professional and efficient organization.

Government Effectiveness and Legitimacy

State Security

Responsibility for national intelligence and security within Torrike is split between three different agencies, the National Security Service (NSS), which is the main government security organization, the National Signals Agency (NSA) which covers all aspects of offensive and defensive electronic intelligence and the Military Intelligence and Security Service. The latter falls under the Ministry of Defense, but can be regarded as a state‐level agency.

National Security Service (NSS)

The National Security Service of Torrike is a state agency that is part of the Ministry of Justice. The Director of the NSS, who is a civil servant with a law enforcement background, reports to the National Police Board. The service’s prime functions are constitutional protection (e.g. the protection of the state against external espionage and internal dissent) and counter‐terrorism.

National Signals Agency (NSA)

The NSA is an inter‐ministerial state agency that established in late 1990s in an attempt by the government to unify the civilian and military expertise, and better organize the extensive capabilities of the country in the area of signals, frequency management and protection of the communication capabilities and infrastructure.

Civil Defense

Civil Defense within Torrike is the responsibility of the MOD, however, the responsibilities of the military in this sphere have been gradually eroded over the last decade and these have increasingly been transferred to the National Civil Emergencies Service.

Regional Alliances

Torrike’s membership of the SCO represents its major regional commitment. Through its partnership with Arnland and Bothnia, Torrike seeks to influence their views and actions in a direction favorable to Torrike. Although neither Framland nor Otso are full members, the SCO provides a forum for Torrike to engage these nations in meaningful dialogue on a one‐to‐one basis.

Elections

Torrike’s electoral structure works at three levels; the Presidential, the national government and the local government. Each of these elections gives the populace an opportunity to express their views on the governance of the country and the direction in which the country is being led.

The three levels of election are deliberately separated from each other. Presidential elections take place every seven years, while Parliamentary elections are held every five years. Local elections are held every year for one third of the total number of seats in the appropriate assembly.

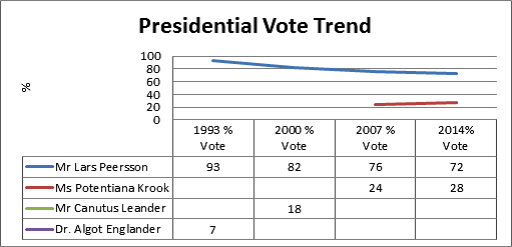

Presidential Elections. The current President won the last election and is serving his fourth term of office. The last election was held in 2014 and the next is due in 2021. The results shown below indicate that his share of the vote has reduced each time. However, the major surprise at the last election was the degree of support for a candidate who espoused a more aggressive ‘Greater Skolkan’ approach than Peersson and this has had an influence on national politics since.

| 2014 Election | |||||

| Candidate | 1993 % Vote | 2000 % Vote | 2007 % Vote | 2014 % Vote | Electorate |

| Mr. Lars Peersson | 93 | 82 | 76 | 72 | 1,808,494 |

| Ms. Potentiana Krook | 24 | 28 | 703,303 | ||

| Mr. Canutus Leander | 18 | ||||

| Dr. Algot Englander | 7 | ||||

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2,511,797 | |

| Total | 2,630,568 | 2,555,956 | 2,887,123 | 2,945,123 | 3,401,758 |

National Elections. The TUP has dominated national elections for the last 25 years and shows no signs of losing that dominance. In combination with the TNP, it ensures that a broad Skolkan centric policy is maintained at the center of Torrikan politics.

| 2014 Election | |||||||||

| 1984 % Vote | 1989 % Vote | 1994 % Vote | 1999 % Vote | 2004 % Vote | 2009 % Vote | 2014 % Vote | Electorate | Seats | |

| Torrikan Unity Party (TUP | 56 | 58 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 56 | 53 | 1,586,580 | 96 |

| Torrikan Nationalist Party (TNP) | 30 | 31 | 30 | 32 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 987,871 | 56 |

| Torrikan Prosperity Party (TPP) | 10 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 329,290 | 14 |

| Liberal Party of Torrike (LPT) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 89,806 | 5 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2,993,547 | ||

| Seats | 1984 | 1989 | 1994 | 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 |

| Torrikan Unity Party (TUP | 96 | 99 | 94 | 96 | 97 | 96 | 91 |

| Torrikan Nationalist Party (TNP) | 51 | 53 | 51 | 55 | 53 | 55 | 56 |

| Torrikan Prosperity Party (TPP) | 17 | 12 | 21 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 19 |

| Liberal Party of Torrike (LPT) | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

Suffrage. Torrike operates a system of universal suffrage where all citizens aged 18 or over have the right to vote in local and national elections. There are no exceptions to this rule, and even prisoners have the right to vote. Compared to many countries, the voter turnout is quite high. For example in 2009, there were 3,401,758 Torrikans eligible to vote. 2,993,547 actually voted in the national elections, or 86% of the eligible voters.

International Political Issues

Arnland Relations

Arnland’s Nuclear Power Plants. The deteriorating situation in Arnland requires Torrike to prepare contingency plans for the safety of Arnland’s nuclear power plants. Prospective scenarios include a terrorist assault on the plants resulting in either a catastrophe or the plant being held for ransom. Intervention by Torrike, with or without an invitation from Arnland is a distinct possibility.

Karlskrona Naval Base. The location of a major naval base in the heart of Arnland is a potential source of conflict. Efforts by the Arnish authorities to hold the base to ransom could lead to conflict. An alternative scenario is that the NOM launch an attempted attack on the base. Any premature or overly heavy handed Torrikan response to an impending crisis over Karlskrona could also lead to trouble.

Potential Collapse of Arnland. Notwithstanding its aim of reabsorbing Arnland, Torrike wants such a process to be carefully managed. Any sudden collapse could generate large numbers of refugees which Torrike is not well placed to manage. In the event a collapse looks imminent, Torrike may choose to act pre‐emptively.

The Arctic

Torrike is desperate to benefit from what it believes will be a natural resources bonanza in the Arctic region. Currently physically blocked by Norway, Torrike may consider radical plans to guarantee access.

Competition with Denmark

There is an ongoing dispute with Denmark over the rights to exploit resources in the Skagerrak area. Torrike considers its access to be a matter of historic right and regards the refusal of Denmark to cooperate as a potential source of conflict.

The Baltic Approaches

Torrike is concerned to exercise the maximum possible control over the Baltic Approaches. Strategically it feels vulnerable and considers Denmark insufficiently reasonable on this topic. The development of the proposed Olvana financed route through Torrike may ease this issue, or exacerbate it.

Interaction with Poland

Torrike has a number of resource disputes with Poland, including fishing rights in the Baltic. In addition, Torrike claims that Polish vessels are polluting the area heavily and reducing the catch. In themselves these disputes seem minor, but the Torrikan attitude towards Poland is irrationally bad tempered, which does not aid their peaceful resolution.

TTW Dispute with Framland

There is an ongoing dispute between the two nations over a small area of the Baltic Sea to which both have claims. It is a source of irritation, but unlikely to generate any conflict.

International Relationships

Torrike is a sophisticated and successful trading nation, with very clearly defined and ambitious regional aspirations. As such, its Foreign Relations are both complex and nuanced. The more extreme advocates of the Greater Skolkan vision divide other nations into the helpful, the obstructionist and the irrelevant, depending on a nation’s view of Greater Skolkan. However, the Government’s views and the attitudes derived from those views are much more subtle. As its economic success has grown and its military has become increasingly effective, so Torrike has flexed its muscles. Peersson’s policies since the early 90s have built a coherent and assertive state which has proved increasingly argumentative in its relations with other powers. The aim is not so much to be disruptive for its own sake, as to establish Torrike’s position as a serious regional player, who must be factored into any calculations and arrangements that any other nation wishes to make.

Foreign Policy

Torrike’s foreign policy is based firmly on the overriding principle that Torrike is the natural regional leader and this needs to be acknowledged by outsiders at the same time as persuading the regional nations to align themselves under Torrike’s benevolent guidance. To this end, the aim is to either exclude or manipulate external influence, while adopting a range of policies designed to bring the ‘Skolkan’ closer to Torrike’s position. The unstated driving aim remains the reintegration of the former Empire countries under Torrikan leadership. Torrike’s policy is therefore concerned with ensuring that the UN, the EU and NATO influence in the region is minimized and that all interactions with non Skolkan regional nations are conducted on a bi‐lateral basis. Torrike’s intent is to present itself as a ‘reasonable’ nation to its neighbors, but one that has teeth to back up its perfectly natural ambitions. Torrike sees the SCO as an essential mechanism for achieving its regional ambitions and as such, active management and direction of the SCO is one of the major planks in its foreign policy platform.

On matters where the Skolkan issue is not affected, such as famine in Africa, or the broader world finance issues Torrikan foreign policy is both as constructive and as selfish as any other sophisticated Northern European nation.

Global Politics

Torrike does not see itself as a major player on the world stage, however, it does consider itself as a significant regional power and as the natural spokesman for the aspirations of its region and expects its views to be given precedence on any matter that affects the region. As a result it is an active member of the UN and other fora where it can advance its aspirations, or block those of others that do not suit its purposes. Torrike has built relationships with other powers where mutual benefit may accrue. Thus, Torrike does not merely seek support from Olvana on important issues, but also actively supports Olvana’s positions on matters of Olvanai concern. Torrike is also prepared to support other states in the UN who have adopted ‘difficult’ positions as a method of building up future support for Torrike. The furtherance of Torrike’s strategic aim remains the guiding principle in all its interactions with other nations.

This approach applies even in its relations with the developing world. Torrike provides limited aid to developing countries and encourages young people to participate in small scale development projects in Third World countries. Unusually perhaps, Torrikan aid is not tied to the purchase of Torrikan products. However, trade politics are played effectively in Torrike’s areas of special expertise and the country has built up a coterie of nations that will support Torrike in international fora through beneficial trade deals.

Relations with the UN. Torrike is an active participant in UN activities and has built a reputation as a solid if unpredictable and occasionally difficult member. Torrike’s aim is to ensure that any debate that affects its home region recognizes it as the natural leader of the region and gives primacy to its views. Torrike is a long way from achieving this goal, but it has made significant progress. By building up a band of supporters in the Third World and supporting the positions of Olvana, and increasingly South American, as well as those of other significant non‐aligned nations, Torrike has ensured that its positions are taken into account on matters of importance to it. In further support of its aim, Torrike endeavors to present its positions rationally and is an enthusiastic and productive member of many UN committees and Agencies. By applying itself efficiently to matters that do not interest it, Torrike has constructed a foundation for its intervention on matters that do.

Relations with the EU. Torrike’s relations with the EU are complex. On the one hand, it is a major trading partner and both a major market and a major supplier to Torrike. On the other hand it is a potential threat to Torrike’s desired regional hegemony. Torrike considers the EU as a political block to be somewhat dysfunctional, but is well aware of the potential of the bloc should the member countries agree on a single course of action. Torrike’s aim is essentially to ensure that it never pushes the EU into taking concerted action. It considers that providing it pursues its ambitions carefully, it can play one member off against the others and ensure that in the final event, nothing is done. As a backup, Torrike believes that decision making in the EU is so glacial as to give Torrike the time to recover from any fundamental error of judgement in its relations with the EU.

On the economic front, Torrike finds the constant stream of regulations, standards and directives flowing from the EU to be a major irritant. Although Torrike is under no obligation to comply, it must do so if it wishes to trade with the EU countries. Since maintaining two different sets of conditions – one for EU trade, one for non‐EU trade – would be unduly onerous for Torrike’s economy, Torrike follows the EU set. In effect it’s manufacturing, transportation and related industries are being forced to conform to rules and regulations over which it not only has no control, but for the most part, over which it does not even have a say.

Relations with NATO. From a political perspective, NATO is a major concern to Torrike. Traditionally, Torrike’s sole concern was to ensure that in the event of a conflict, that it was not caught between NATO and the Warsaw Pact (WP) if they decided to fight over Norway. In the immediate period after the demise of the WP, NATO seemed somewhat aimless and was not a consideration as the TUP established itself as Torrike’s natural ruling party and Peersson consolidated his position as national leader. However, in the last decade, NATO has seemed more aggressive and appears to Torrike to have become more interventionist. Given the long border with Norway, the spread of NATO across the southern Baltic and the Air Policing role in the Baltic States where NATO provides air defenses, Torrike has become increasingly concerned about NATO’s ambitions and actions.

In pursuit of its aim of minimizing NATO involvement and influence in the region, Torrike conducts an extremely active anti‐NATO information operations campaign both within the country and externally. The message is tailored to the audience; thus internally the message is that NATO is an unelected interfering outsider that has no place in the region. To the Baltic States, the message is that NATO really does not care about them and considers them more bother then they are worth and so it would be much better to reach an accommodation with Torrike bi‐laterally on any areas of mutual concern. To the broader world, the message is that NATO is a moribund organization that has outlived its usefulness and is more of a hindrance than a help to world peace. If the NATO nations wish to waste their money on a talking shop that is up to them, but that does not give them the right to interfere in the legitimate affairs of other nations in order to justify their existence.

Relations with Olvana. Torrike’s relationship is based firmly on mutual self-interest and works best where those coincide. Torrike’s aims are largely political, but financial interests have become increasingly important. From a Torrikan point of view, Olvana offers a valuable strategic backer in international fora, especially the UN, which allows Torrike to pursue its interests with confidence that its voice will be heard. Increasingly, Olvana has proved to be a valuable market for Torrikan raw materials and to a lesser extent high technology products. From Olvana’s perspective, it gains another supporter in the UN and can use Torrike as a method of exerting influence in Northern Europe. Torrike is a valuable, and reliable, source of various commodities, not least rare earths and potentially, uranium. It is also an area into which Olvanai investment can be exploited, although all business deals are nominally free of any strings. Torrike and Olvana are bound together by bilateral and multilateral agreements to share technology and industrial production. A trade agreement between the two countries, signed in 2003, calls for trade turnover to increase 28% over the 2008‐2012 plan period.

Olvanaan leaders are in "advanced talks" with the Torrikan government to build an alternative to the Öresand Strait between Denmark and Arnland. The industrial improvement of the Goteborg to Tyr rail link would run from the Skagerrak to the Gulf of Bothnia. The aim will be to upgrade the existing rail system to maximise freight capacity. This may also include investment in the Gota Canal. This would allow imported Olvanai goods to be assembled for re‐export through Torrike and beyond, to Bothnia, the Baltics, Otso and Framland, by bypassing the Öresand. In addition to the economic benefits through expansion (including new manufacturing jobs), competition, urban and rural development, and the ability to have an alternate for the movement of strategic assets, the potential political implications are also significant.

Relations with Tolima. Torrike has had few formal dealings with Tolima to date, except the occasional sideline discussion during SCO meetings. However, Torrike has supported Toliman positions in the UN and Tolima has returned the compliment.

Regional Actors

Norway

Torrike’s relationship with Norway is variable, with a considerable difference between the philosophical view of Norway and day‐to‐day relationships. In some respects, Torrike blames Norway for precipitating the breakup of the Skolkan Empire, even though the Empire’s overlordship of Norway was always tenuous at best. Politically, Torrike’s relationship with Norway tends to be moderately tense. Norway represents the most immediate presence of NATO in the region and therefore needs to be handled carefully. At the same time, Norway clearly opposes any effort by Torrike to make itself the regional leader, albeit only by political activity. There is also the feeling among Torrike’s political elite that Norway sets the wrong example to the region in that it is a successful small nation, whereas the Torrikan message is that for small nations to survive, they need to link up to more powerful ones.

Economics also play a role. Having missed out on the North Sea Oil boom due to geographic issues, Torrike is concerned that it will now lose out on the impending Arctic bonanza, because once again it is blocked physically by Norway. This is particularly ironic since when Norway declared independence in 1905, the Empire had initially tried to retain northern Norway to give it an opening to the Norwegian Sea and an ice free outlet to the wider world. Skolkan was unable to sustain this claim, but it has not been forgotten. The idea was resurrected in the mid-90s, with an offer to buy, or lease, a slice of Northern Norway.

The bid was rebuffed, but Torrike still maintains the ambition. On a more practical level, the two nations share an extremely long border (2,400km) and so practical issues always have to be taken into account when discussing higher level aspirations. The border facilitates trade and although both countries set tariffs, trade exchange between the two countries generally flows freely. Additionally, there is considerable cross border investment between the two nations, with investment flowing in both directions. There are also a number of possibilities for shared infrastructure and infrastructure investment.

Military links do not extend beyond the normal operational level courtesies and cooperation. There is a reasonable exchange of essential information and cooperation on SAR matters is extremely good. For the most part, however, relations are proper rather than cordial.

Culturally, Torrikans have never lost their sense of superiority over the Norwegians. However, there is actually a great deal of shared heritage between the two nations and the open borders and free trade between them only reinforces those ties.

Diplomatically, there are the normal exchanges that would be expected between two modern nations who share a mutual border. Cooperation on matters of mutual interest is generally good, although the definition of what constitutes a mutual interest is often open to question. Each country maintains full diplomatic representation in the other nation

Denmark

For the most part political relationships with Denmark have been historically tense. In the formative days of the Skolkan Empire, Denmark proved an obstacle that could not be overcome. More recently, Denmark is seen as one of the front runners of NATO interest in the region as well as that of the EU. As such, Denmark is seen as a potential obstacle to Torrike’s regional aspirations. Denmark’s geographic position adds to Torrike’s concerns, not least because it would be a natural staging post for NATO in the event of a confrontation and could easily block access to the Baltic and so increase pressure on Torrike. Torrike also has a historic and extremely vague claim to Bornholm Island, but this has never been pursued openly. At a more practical level, the relationship between the two countries is driven by their mutual concern for the situation in Arnland. Although the desired end states of Denmark and Torrike differ radically, each is concerned to keep the situation in Arnland from getting out of hand. Notwithstanding this, there are few military contacts beyond the normal exchange of operating information relating to safety and the professional courtesies expected of neighboring militaries. Cooperation on SAR and related matters is also good.

Trade between Denmark and Torrike flows freely, although both sides apply tariffs on some items. Danish tariffs are largely driven by EU regulations. Investment by each nation in the other runs at a fairly respectable level. In the meantime, Torrike has a vital interest in maintaining relationships that are sufficiently cordial to allow free passage of its trade through the approaches.

Torrike and Denmark enjoy full diplomatic relations and representation. The situation in Arnland draws them together more closely than either would perhaps normally wish, but working relations tend to be reasonably harmonious.

Germany

Torrike’s relationship with Germany is generally cordial, although there are points of tension in areas such as fishing rights and natural resource exploitation within the Baltic area. Torrike’s main concern with Germany is that it is a powerful member of NATO and would be well placed as a base from which to launch any confrontation. There are no specific military ties beyond the normal level of professional courtesies and cooperation accorded to neighboring militaries. Both nations cooperate on safety regulation within the Baltic area and on SAR matters.

Economically, relations are good with trade flowing freely in both directions, subject to the usual tit‐for‐tat tariffs centered around EU regulations. Cross border investment is more contentious, however, as Torrike resents the fact that Germany restricts foreign ownership of German companies, but expects no such restrictions on German companies abroad. Torrikan politicians have blocked some recent minor acquisition efforts by German companies to send a message that reciprocity is expected.

There are few cultural ties between the nations and as part of its ‘message’ to Germany, Torrike has blocked German companies from bidding for major infrastructure projects within the country. As these are largely promoted and funded by Olvana, this has been a largely symbolic act.

Torrike and Germany enjoy full and largely cordial diplomatic relationships, with the normal level of representation in each country.

Poland

Torrike’s relationship with Poland is less comfortable than that with Germany. Although there is no tradition of hostility between the two nations, there have been several disputes with regards to fishing rights, overfishing, and the exploitation of natural resources in the Baltic during the last 20 years. Each side considers that the other assumes an unreasonable air of ownership over matters that could be settled amicably. This, combined with Poland’s open derision of Torrike’s dream of a reconstituted Skolkan under their leadership, makes for somewhat prickly relations. Torrike’s habit of trying to convince the Baltic States that Poland is a threat to their independence does not help matters. Notwithstanding this, both countries have full representation and are not averse to cooperating on matters of mutual interest.

There is almost no contact between the two nations militarily and the exchange of information is kept to the absolute minimum commensurate with a shared area of interest. The sole exception is that of SAR in the Baltic region to which both nations contribute in a manner appropriate to their resources.

There is a reasonable level of trade between the two nations, subject to the usual vagaries of trade between a member and non‐member of the EU.

Lithuania

Torrike’s relations with the Baltic States are complex. All the nations are members of the Council of Baltic Sea States and much of their interaction is addressed through that forum. However, Torrike’s overriding aim is to settle any issues in a bilateral forum rather than in a wider discussion. Torrike has the normal fishing and trade disputes with Lithuania, but has no desire to sweep Lithuania into its orbit. The campaign to persuade the Baltic States that Poland represented a threat to their independence being a case in point. A more subtle approach, to the effect that neither the EU nor NATO really cares about small States has had rather more success in certain areas. However, Torrike does really offer any sort of alternative, let alone an attractive one and its appraisal of the success of this approach seems over optimistic.

Trade and economic relations between the two countries are largely uncontentious, although neither represents a major trading partner for the other. There is the usual level of diplomatic representation in each country.

Latvia

Torrike’s relations with the Baltic States are complex. All the nations are members of the Council of Baltic Sea States and much of their interaction is addressed through that forum. However, Torrike’s overriding aim is to settle any issues in a bilateral forum rather than in a wider discussion. Torrike has the normal fishing and trade disputes with Latvia, but has no desire to sweep Latvia into its orbit. The campaign to persuade the Baltic States that Poland represented a threat to their independence being a case in point. A more subtle approach, to the effect that neither the EU nor NATO really cares about small States has had rather more success in certain areas. However, Torrike does really offer any sort of alternative, let alone an attractive one and its appraisal of the success of this approach seems over optimistic.

Trade and economic relations between the two countries are largely uncontentious, although neither represents a major trading partner for the other. There is the usual level of diplomatic representation in each country.

Estonia

Torrike’s relations with Estonia are somewhat different to those with the other two Baltic States. Although many of the same themes are present, the specifics are heavily influenced by the confrontational relationship between Bothnia and Estonia. Torrike, therefore, seeks to make the best of the situation, with Estonia providing an outlet for anti‐NATO propaganda and an example of the dangers of letting NATO operate in Skolkan’s area of interest.

Despite this, Torrike does seek to distance itself somewhat from Bothnia’s position and relations with Estonia are at least polite, if not cordial. Trade between the two countries is largely unaffected and remains reasonably buoyant and both nations have diplomatic representation in the other.

Otso

Torrike has no particular view of Otso, or intentions towards it. Otso’s role as a buffer between ‘Skolkan’ and Donovia is seen as valuable and likely to become even more so if Torrike achieves its ambitions. The full range of normal diplomatic representation is established in both nations.

Torrike is always conscious of the need not to be seen as trying to compromise Otso’s neutrality and therefore, military contacts between the two nations are very limited. Otsan observers have been invited to some Torrikan exercises and Otsan officers have delivered some lectures to the Torrikan Staff College on Peacekeeping Operations, but that is the limit of their interaction.

Relations on the economic front are good and Torrike is keen to keep them so. Torrike provides Otsonian companies with advanced technology and their respective industries have established a number of joint ventures. On both the social and infrastructure front, there are only limited contacts. The main interaction is through the passage of Sami tribesmen across the respective borders in the far north.

Information exchange between the two nations is open and fairly extensive, with the normal government to government interaction.

Bothnia

On the economic front, the Skolkan Economic Community (SEC), has played a major role in stabilizing Bothnia’s economy and helping it to remain viable. Torrike has, of course, played a major role in ensuring that the SEC has been so supportive, which provides it with an instrument through which influence and, if necessary, pressure can be applied. Torrike has provided Bothnia with considerable technical support and technological expertise to assist it in the modernization of its industries. Trade between the two nations is extensive, with military equipment being an especially notable item.

Although there are strong historic ties between the two nations, the strong sense of identity and national pride that each nation possesses limits social links. The obvious Torrikan air of superiority has not helped in this sphere. Mutual infrastructure maintenance is driven largely by trade needs as there is little else in common on this front.

There is an extensive mutual exchange of information at all levels between the two countries, but it is definitely not a transparent exchange. Each side has its own agenda and its own secrets and considerable attention is devoted to pursuing the first and protecting the second.

Framland

Torrike’s relations with Framland are essentially harmonious and benign, not least because Framland’s politics are considered to be largely compatible with Torrike’s own. Because of this cooperation with Framland is considerably better than with Bothnia. The bilateral relationship between the two nations is extremely good and Framland is seen as a useful ally in discussion on matters concerning the Arctic. Torrike has expressed no adverse views on Framland’s existence and for the most part is fully supportive of its independence, not least because it already exercises a good deal of influence on those areas it considers important. There is an element of a ‘One Nation, Two Countries’ approach to their relationship and this is reflected at all levels of interaction with the exchange of information between the two governments being surprisingly open.

This applies across all areas of activity. Torrike provides a good deal of training to the Framish military and also feeds Situational Awareness data to the Framish operations center while taking feeds from Framland in return. Economically, Torrike and Framland are intertwined, with extensive mutual holdings of each other’s companies. Socially, the two peoples have extremely close historic ties and in many respects do not see themselves as separate races. Framland is heavily dependent on Torrikan transportation infrastructure and there is considerable synergy between the nations on energy infrastructure, with mutual maintenance of common infrastructure.

Arnland