Difference between revisions of "Africa"

m (Tag: Visual edit) |

m (→Physical Environment) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 287: | Line 287: | ||

*Arable land | *Arable land | ||

|| | || | ||

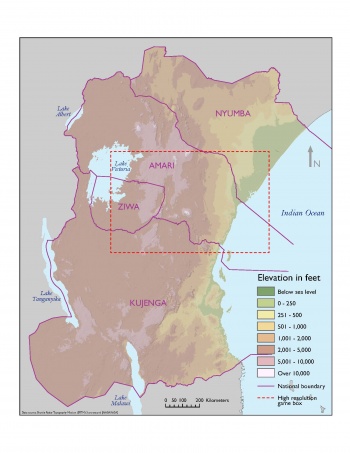

| − | * | + | * Borders the Indian Ocean. |

| + | * Encompasses Lake Victoria, Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganika. | ||

| + | * Terrain varies from a significant rift valley in the central region, high mountains and arid desert lowlands, as well as coastal plains. | ||

| + | * Climates range from tropical to semiarid in the east; warm desert in the west; and humid near the coast. | ||

|| | || | ||

*Difficult to grow | *Difficult to grow | ||

Revision as of 18:36, 7 February 2020

The purpose of the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE) Africa is to provide the US Army training community with a detailed description of the conditions of four composite operational environments (OEs) in the African region. It presents trainers with a tool to assist in the construction of scenarios for specific training events but does not provide a complete scenario. DATE Africa offers discussions of OE conditions through the political, military, economic, social, information, infrastructure, physical environment, and time (PMESII-PT) variables. This DATE applies to all US Army units (Active Army, Army National Guard, and Army Reserve) and partner nations that participate in DATE-compliant Army or joint training exercises.

Over 795,000 square miles comprise DATE Africa, a varied and complex region which ranges from Lake Victoria in the west to the Indian Sea on its eastern coast. The region includes the fictional countries of Amari, Kujenga, Ziwa, and Nyumba.[1] The region has a long history of instability and conflict; ethnic and religious factionalism; and general political, military, and civilian unrest. In addition to these internal regional divisions, outside actors have increasing strategic interests in the region. DATE Africa thus represents a flashpoint where highly localized conflict can spill over into widespread unrest or general war.

(See also Using the DATE and TC 7-101 Exercise Design).

Contents

Key Points

- The countries in the region have experienced dramatic changes in governing regimes over the last few decades.

- Political, economic, and environmental changes have created societal pressures that spawn conflict between nations, political factions, international players, and potential threat actors.

- The complex tapestry of ethnic, tribal, linguistic and religious loyalties make diplomatic and military operations in the region difficult.

- US forces may be required to conduct operations in the region in a wide range of roles and will likely operate in a combined effort with other forces.

Discussion of the OEs within the DATE Africa Operational Environment

Republic of Amari

Amari, with its capital at Kisumu, is a functioning and relatively stable democracy, receiving significant support from the US and other western countries. A new constitution, implemented seven years ago, attempted to create a framework for better governance, with good results. Ethnic and tribal tensions continuously play out in multi-party politics, which has led to a history of electoral violence and distrust of the government. The last election was uniquely free of the violence of past elections. Other concerns include border security, instability spillover from neighboring countries, regional competition for resources, and terrorism.

Amari gained independence from a western European colonial power fifty years ago; a time when colonial powers were divesting themselves of their African colonies. The government consists of an executive branch with a strong president, a bicameral legislature, and a judiciary with an associated hierarchy of courts. Amari is making significant progress in areas of good governance but still struggles with institutional corruption. The new constitution has attempted to create a framework for better governance with good results. Other concerns include border security, instability spillover from neighboring countries, regional competition for resources, and terrorism.

The Amari National Defense Force (ANDF) is the state military of Amari. Its composition, disposition, and doctrine are the result of years of relative peace. Internal security and the constant struggle against border incursions continue to shape its structure and roles. The ANDF consists of the Amari Army, Air Force, and Navy. Amari paramilitary forces include the Border Guard Corps (BGC) and Special Reserve Force (SRF). The ANDF is a well-integrated and professional force with good command and control and high readiness. It has a limited force projection capability and a mix of static and mobile forces. Amari is an active contributor to both regional and international peacekeeping forces and has hosted such forces within its borders.

Republic of Ziwa

The Ziwa People’s Defense Force (ZPDF) is the state military of the Republic of Ziwa. Its structure and focus has adapted over the last decade alongside the country’s economic development. The ZPDF consists of the Ziwa Ground Forces Command (ZGFC), Ziwa Air Corps (ZAC), and the National Guard. Ziwa’s military relations with its neighbors—Amari to the north and Kujenga to the south—are generally stable, despite sporadic low-level incidents along the border. Border control challenges contributed to the forward deployment of dedicated maneuver elements and leveraging of former rebels to ensure the appearance of security.

Multiple threats exploit Ziwa’s dependence on natural resources and external power generation and transmission. Brutal militants in the northeast mountain area (“The Watasi Gang”) and pockets of ethnic rebels throughout the country continue to plague stability and keep the military at a continually high operational tempo. Although both Kujenga and Amari have active security agreements with Ziwa, rumors persist of their covert support to the Ziwa rebels.

Republic of Kujenga

Kujenga gained semi-independence fifty-six years ago under a post-colonial United Nations mandated trusteeship. Three years later, Kujenga gained full independence, establishing a constitution built on a single political party system.

Working under the UN mandate, the outgoing colonial power lent support to the group of elites who had made up the bureaucracy under colonial rule. These elites united under the political party People of Change (POC). They have since controlled the government through successive elections, except for a brief experiment with multi-party rule seven years ago that ended five years later with the subsequent election. After independence, Kujenga established diplomatic relations with the United States. Relations between the two countries have been strained at various times because of Kujenga’s tight-knit oligarchic political structure and repressive tendencies. Ongoing tensions and violence between the Kujengan government and the Tanga region brought especial US condemnation. The Kujengan government is focused on addressing rampant corruption and government inaction, but the country has also experienced a shrinking of democratic space.

The Kujenga Armed Service (KAS) is the state military of the Republic of Kujenga. It emerged from a somewhat turbulent past and a range of internal security challenges. Kujenga’s military relations with its neighbors are relatively stable, although border security issues, particularly in the Tanga region, are increasing the risk of regional conflict. The KAS consists of the Kujengan Army, Kujengan National Air Force (KNAF), Kujengan National Navy (KNAV), and Security Corps. Kujenga’s primary internal security concerns include Tangan separatists, violent bush militias in the central mountains, and the brutal "Army of Justice and Purity" guerrillas in the Kasama region. External threats include border incursions by presumed Amari paramilitaries and cross-border smuggling.

Democratic Republic of Nyumba

The government is authoritarian in all aspects. Beginning fifty-nine years ago, a military coup overthrew the newly elected civilian government, lasting only six years before an Islamist government took power. While the government is based on its interpretation of Sharia law, tribal traditions and influences permeate the government as well. Economic, religious, ethnic, and tribal interests complicate Nyumban politics and have led to decades of civil war and other internal conflicts. These conflicts have threatened border countries with refugees and provided a safe haven for terrorists, insurgents, criminals, and other disruptors. These deep-seated challenges show no signs of dissipating.

The Nyumban Armed Forces (NAF) is the state military of Nyumba and is key to the country’s stability. It has experienced significant challenges from various threat actors in Nyumba, distrust within its ranks, and from politicians. Civilian distrust is particularly high, leading to widespread tribalism and the rise of armed militias. Its composition and deployments are driven by political desires to maintain control of key forces and the de facto ceding of territory to tribes or armed groups. The NAF consists of the Nyumban National Army (NNA), the Nyumban Armed Forces Air Corps, and the Nyumban Navy. The Nyumban National Security Service controls a paramilitary group, the Rapid Security Forces (RSF) which is usually deployed in support of border and anti-insurgency operations. The NAF has inherited a varied structure and culture due to several regime changes and a colonial legacy. The lawlessness of the territory and general instability has heightened both political and military leaders’ wariness of the forces.

Strategic Positioning

This OE is one of the most politically dynamic regions in the world. Almost nowhere else have geopolitical forces and regional ambitions combined to produce such volatile results. State developments ranging from gradual reforms to often violent regime change have occurred throughout the region's history. Although the region may not have been the primary focus of global geopolitical contests, it has often been a factor in the larger geopolitical landscape. This volatility is not likely to change in the coming years as greater multipolarity continues to increase throughout the region.

Coinciding with increased international interest, the region's states grew stronger over the past several years, exerting their sovereignty in ways that challenge the post-Cold War development and humanitarian models. International players increased pressure to gain a foothold on the continent. As the countries in the OE forge new international relationships, they find a range of willing partners with a diverse set of motives. Non-state threat actors also find fertile ground for extremist messages. Uneven economic growth and the injection of international anti-terror military aid empower some states while channeling resources to specific interest groups in power, specifically to the executive and security sector. However, this will not guarantee stability or equitable human development. Rather, the region may see more money pouring into countries, but with greater partisan international interests and increased conflict.

Strengthening centers of power may prevent non-violent political change from emerging. Ambitious leaders on the periphery are likely to resort to violence to unseat ruling regimes that themselves came to power as products of deeply embedded ethnic conflicts, cross-border regional power projection, and divisive domestic inequalities. The OE is often viewed as a 'political marketplace,' the challenges of which could begin to lead the region down a violent path. The region has a history of weathering changes in international attention, while also managing local political conflicts and economic problems. National leader legitimacy deficits co-exist within an international context that often undermines the development of local solutions. Even as regional cooperation is increasing stability and the level of cross border interference has declined, the future is anything but certain. The ever-present international, regional, and national challenges continue to strain the ability and capacity of national and regional institutions to regulate and manage nonviolent change.

Regional Views of the US

The countries of the OE voice mixed views of American soft and military power. There is little consensus about U.S.-style democracy and there are many in the populations who oppose the spread of American ideas and customs in Africa and around the world. At the same time, many in the region still believe the U.S. respects the personal freedoms of its people and they aspire to similar freedoms. While the U.S. and other nations are involved in widely-popular peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, the presence of outside forces has been a rallying cry for disenfranchised groups. The general pull away from U.S. intervention in the region has been aided by aggressive inroads from other external countries, such as Olvana, that promise to supply an alternative to previously undisputed economic and military power.

Regional PMESII-PT Overview

Political

The governments in DATE Africa are vulnerable to widespread corruption, entrenched political leaders who repeatedly amend constitutions to extend their rule, and the historical absence of a democratic political culture. They are apt to place legal restrictions on civil society. A history of coups, civil conflicts, and political stalemates between opposing factions suggest a potential for democratic backsliding across the region. Weak and failed states contain ungoverned spaces that provide operational bases for numerous irregular threats.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics |

|

|

|

|

Military

The countries represented in DATE: Africa are a cross-section and composite of states and state forces. State forces have evolved from a diverse set of conditions including colonial histories to a succession of regime changes and revolutions. They are generally pragmatic in both structure and equipment - the result of constrained budgets and constantly changing threat conditions. The forces of the more modernized countries, such as Amari and Ziwa, are generally more integrated, better equipped, and more professional. At-risk countries, such as Kujenga and Nyumba demonstrate tribal or ethnic segregation, degraded readiness, and a structuring for regime survival. Participation in regional or international peacekeeping forces and exercises is often as much to train and equip their own forces as to develop interoperability and cooperation. A variety of threat groups and endemic criminal activity throughout the region contend to destabilize governments or build power in difficult-to-govern areas.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military |

|

|

|

|

Economic

The economic conditions in the four countries cover a wide spectrum. Ranging from modern economic systems to reliance on traditional cash-only systems. In all of the countries the underlying structure of family and tribe motivate most economic transactions and policies.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic |

|

|

|

|

Social

In Sub-Saharan Africa, UN population growth forecasts exceed 2.0% per annum through 2035, with the majority of the population under age 25 through the year 2050. Sub-Saharan Africa’s global share of 15-24 year olds will increase from 14.3% to 23.3% over the forecast period. Under these circumstances, mega-cities will continue to grow rapidly, poverty will persist, and governments will struggle to provide basic services. Insurgent and terrorist groups will seek to exploit these conditions: competing with the state to provide social services; employing violence to intimidate political opposition; using terror attacks to provoke external actors into de-legitimizing military interventions; and aggressively recruiting among the region’s youth.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social |

|

|

|

|

Information

The OE countries all recognize the importance and influence of information media and its control. Approaches range from low technical capabilities with tight government controls to rapidly modernizing technical capabilities with ineffective attempts by the government to control the public's perceptions. New means of information sharing using modern technology are rapidly adopted by the population unless the government intervenes in an attempt to control information flow. Countries jump directly from limited land-line telephone systems to ubiquitous cell phone use. Distances and improvements in technology, software, and infrastructure allow African countries to implement new information systems at a very rapid pace. In several instances, African countries are on the cutting edge of adopting new information technology to enhance the public's standard of living. Other instances see the leadership of a country attempting to control access to information systems to remain in power and to exploit it for their own benefit.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information |

|

|

|

|

Infrastructure

African infrastructure is expensive. Long distances, low population densities, uneven management, and intraregional competition contribute to these costs. African infrastructure projects emphasize expensive rehabilitation over basic maintenance. The World Bank estimates that about 30 percent of Africa’s infrastructure requires rehabilitation – even more in rural and conflict-prone areas.

Despite the cost, both domestic and international players are keen to expand Africa’s infrastructure. States control most infrastructure systems, but public-private partnerships (PPP) are increasingly more common. The World Bank and international development finance institutions provide most of the financing, followed by domestic government financing. Olvana is the largest financier and constructor of African infrastructure.

The typical project involves a consortium of non-African state development agencies, international government organizations, private financiers, and construction companies. Following the financing announcement, spending or progress is hard to trace until the project is complete. A large portion of the announced projects are either scaled back or never completed. In some cases, competing projects do not have the demand to justify the large investments.

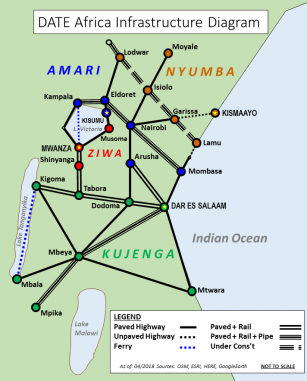

Developed infrastructure correlates with population density. Amari’s main cities: Nairobi, Kampala and Mombasa, are key nodes of the 800-mile Northern Victoria Corridor, a road, rail, and pipeline network. Kujenga follows Amari in both population and infrastructure development, with the competing Dar Es Salaam - Kigoma, DARGOMA, Corridor linking the Indian Ocean port of Dar Es Salaam with Lake Tanganyika and Ziwa’s capital, Mwanza, on the southern shore of Lake Victoria. A major north-south transportation artery runs through Moyale in Nyumba, crossing into Amari just south of Isiolo, through Nairobi to Mbeya, Kujenga in the south. Nyumba, Amari, and Kujenga all compete to be the Indian Ocean gateway of choice to landlocked countries.

Lastly, proposed infrastructure projects are increasingly gathering strong opposition through both standard and social media, quickly gathering international support. The more disruptive to the environment, the more opposition they garner. Examples include port expansion and coal power plant construction in Lamu, Nyumba, and transportation corridors bisecting wildlife ranges in all four countries. While opposition campaigns often start on social media sites and increasingly evolve to on-site demonstrations.

| Amari | Kujenga | Nyumba | Ziwa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Summary/Condition | Have-use-fix | Have-use-don’t fix | Either have but degraded or

never-had |

Have-use-don’t fix |

| Highway Density (mi/100sq mi) | 5.7 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 4.4 |

| Airports w/ Paved Runway >8,000 ft. | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Deep Water Ports/Berths | 1/19 | 4/19 | 1/4 | - |

| Electricity Production/Consumption (MW) | 2300 | 1700 | 130 | 60 |

See also: Amari Infrastructure, Kujenga Infrastructure, Nyumba Infrastructure, Ziwa Infrastructure

Physical Environment

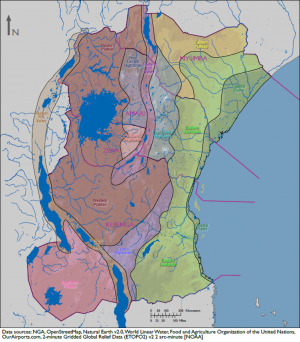

Though making up less than a fifth of Africa, the DATE Africa region includes most of the geographic and climatological features present on the continent. The central features are the Eastern and Western Rift Valleys that run from Kujenga in the south all the way to northwest Nyumba in the north. They are home to the African Great Lakes, which are the origins for both the Congo and Nile Rivers. Their peaks also make up the highest elevations in Africa. Eastward from the Rift, descending savanna and desert meet the Indian Ocean along an expansive coastline containing the natural deep water ports of Dar Es Salaam in Kujenga, Mombasa, Kenya, and to lesser extents Lamu and Kismaayo in Nyumba.

Lake Victoria is the world's largest tropical freshwater lake and sustains an ever-growing population. Despite the relative water wealth contained in the Great Lakes, much of the region suffers from water stress or water scarcity. Man-made crop irrigation is minimal and the major perennial rivers flowing to the Indian Ocean are prone to severe flooding during the rainy seasons.

| Amari | Kujenga | Nyumba | Ziwa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General

Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

| Land Area (sq. mi) | 176,619 | 364,374 | 161,998 | 34,216 |

| Inland Water Area (sq. mi) | 19,956 | 26,437 | 3,350 | 8,900 |

Time

All DATE Africa countries use the Gregorian calendar. However, within that daily routine great importance is paid to the rising and setting of the sun. As is common in equatorial Africa, none of the regional countries observe Daylight Savings Time (DST).

Whilst Western approaches to time are o’clock, or by the clock; regional attitudes towards time are the opposite. In many rural areas some of the elder population might not even have access to a clock or watch. However, their apparent lack of concern for clock time should not be mistaken for an inability to accomplish key tasks. The local populations will commit energy to their tasks with great industry, on their timetable, to achieve their own goals.

Across the whole region there is a much more flexible approach to time. ‘Africa time’ is very much a thing. In short, Africa time means things will happen when they happen; there is no point worrying about what might be. For example; you cannot control the rain, if it rains and crops grow, so be it. Conversely, if it doesn’t rain they will not grow. You cannot plan to harvest crops which depend on rain because you cannot control the rain.

Once the differing approach to time is understood, business with the Amari should be straightforward. Attempting to rush them, or impose a Western approach to time will not be of benefit to either US forces or the host nation. This is the case in the cities as well as the countryside.

Time Zone Observed - UTC +3 (East Africa Time - EAT) DST NOT observed.

Significant Conditions in the OE

Peacekeeping Forces

- International Peacekeeping Forces.

Recent examples of peacekeeping forces with and international mandate include the forces of the UN mission in DATE Africa and the European Training Mission in DATE Africa.

- Regional Peacekeeping Forces.

Recent examples of regional peacekeeping forces include the forces of the Regional Standby Force and the Regional Monitoring Group's Regional Economic Community Security Force.

Private Security Forces

- Corporate Private Security Forces.

Wealthy individuals and businesses may contract the services of corporate security forces. These forces are highly disciplined, organized and trained - recruiting mostly from former elite military and paramilitary forces. They are often used for high-end site and VIP security. They are capable of conducting small-unit, high-risk strikes with state-of-the-art equipment and vehicles. They have a significant intelligence and planning capability. While highly effective and fiercely loyal to their employer, they may have the propensity of over-aggression and risk extra-judicial actions. They may contract local security companies (see below) for mundane activities. Examples: Jaguar Integral Defence Services International (JIDSI).

- Private Security Companies.

Rampant crime and inadequate policing, particularly in the urban areas has led to the rise of numerous private security companies. These companies provide security services for businesses and individuals ranging from static guards to armed response teams. Guarded facilities will likely have barbed wire and monitored cameras. The guards themselves are variously uniformed, from simple reflective vests and caps to military-style garb. They will either be unarmed (batons, irritants) or have a variety of small arms.

The quality and cost of the services may indicate the professionalism of responses and adherence to company rules of engagement. These guards are often well-regarded in the community and may have excellent situational awareness of local activities and dynamics, as well as those of the poorer areas from which they are often recruited.

Note: Non-commercial "neighborhood watches" may exist, but are less likely to be armed or provocative.

See also: TC 7-100 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 5, Noncombatants - Private Security Contractors

Non-Governmental Organizations

A wide range of Nongovernmental Organizations (NGO) operate within the OE. Many are focused on education, medical, and economic development. Some organizations center their activities on humanitarian assistance for displaced persons and supporting camp operations. These groups have typically been vulnerable to attack and corruption by various threat actors in the region. UN and Coalition elements, as well as privately-contracted security have been used by these groups to ensure uninterrupted movement and operation.

See also: TC 7-100 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 5, Noncombatants - Nongovernmental Organizations

Hybrid Irregular Armed Groups

The variety of armed groups operating within the OE is indicative of its complex and dynamic political, economic, ethnic, and religious issues. Their structures are as diverse as their ideological drivers. Most are not pure insurgencies, guerrilla groups, or militias, but rather hybrids of all of these. The key differentiators of these groups is their relative mix of forces and the primary driver of their actions.

Violent Extremist Organizations. There are a number of international or transnational Higher Affiliated Violent Extremist Organizations (VEO) presently operating within the OE. Many of these groups have indigenous origins, but have since affiliated with external groups for support and identity. Others may have their origins outside of the OE and gained a foothold on the continent. These hybrid organizations have the capability to organize and execute high-impact attacks against public targets and may be able to mass to conduct semi-conventional operations across the OE.

Major known groups in the OE include Islamic Front in the Heart Africa (AFITHA) and Hizbul al-Harakat. The volatility of security situations across the OE allow rapid growth and morphing of extremist groups as they position for power and influence. Groups will change their tactics and affiliations to adapt to evolving country and regional dynamics.

Insurgencies. Whether motivated by political, religious, or other ideologies, these groups will promote an agenda of subversion and violence that seeks to overthrow or force change of a governing authority. The composition of these in the OE is almost always a hybrid of insurgent elements and guerrilla forces, depending on the locale, goals, and levels of support. They may act as the militant arm of a legitimate political organization. These groups will undermine and fight against the government and any forces invited by or supporting it. They are likely to target government security forces and even civilians to demonstrate force and create instability. They will conduct small operations, such as kidnapping, assassination, bombings, car bombs, and larger military-style operations. Examples: Amarian People’s Union, Free Tanga Youth Movement.

Separatist Groups. These groups consist mostly of former (losing) soldiers that fought in a previous revolution or coup. Rather than fighting to overthrow the current regime, their focus is to secure a territory and gain officially recognition. These groups will likely have widespread support in the controlled area and view government or external forces as the enemy. They may provide security for commercial or NGO movement for a fee or to curry favor. Separatists will be very protective of their designated borders and may react disproportionately to perceived incursions. Example: Pemba Island Native Army.

Ethnic or Religious Rebel Groups. Numerous conflicts that are highlight ethnic, linguistic, or religious differences have led to the development of ethnicity-focused armed groups. Some groups have developed in self-defense against such groups, then gone onto be violent themselves. Extreme passions of these groups have led to often brazen atrocities, causing massive waves of IDPs. Multiple UN interventions may have temporarily quelled the violence, but long-held grievances give life to renewed violence. These groups may conduct raids, extrajudicial killings, targeted killings of civilians, and summary executions. There have been reports of rebels luring villagers to their town center for execution, often throwing bodies into the village water source to spoil it. These groups may attempt to seize strategic routes to assert control and raise funds. Examples: Army of Justice and Purity (AJP) and Union of Peace for the Ziwa.

Local Armed Militias. These groups usually have a local focus and may be independent or supported by a local strongman. Their forces are mostly comprised of former soldiers or paramilitary who may have fought for the state, but now serve their own interests. They generally carry small arms, but may have additional capabilities, depending on the goals and support. Moderate factions of these groups may conduct demonstrations, vandalism to force political concessions, while more radical factions conduct small attacks, riots, sabotage to enforce a particular ideology. In rural areas, they may be heavily armed and appear almost like a guerrilla force. In urban centers, they may resemble a gang or an insurgent group. Examples: Mara-Suswa Rebel Army (MSRA), Kujengan Bush Militias.

See also TC 7-100.3 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 2: Insurgents and Chapter 3: Guerrillas

Criminal Organizations and Activities

The often unstable economic and security situations across the continent have allowed criminal activity and corruption to flourish. Elsewhere in the world, corrupting and co-opting of government officials by criminal enterprises is usually to gain operating freedom. In the OE, such activities are competitive enablers, intended to gain access to internal and external markets. How these large-scale domestic criminal enterprises and international criminal manifest within the OE are characteristic of each country's circumstances and history.

Criminal enterprises may have a pronounced impact on military operations in the REGION OE. Dominant criminal elements may view external military forces as a threat to their territorial control, while less-powerful organizations may look to exploit shifts in security and rules of engagement to gain access to markets or power.

The main categories of organized criminal enterprises within the OE include:

- Drug Trafficking

- Human Trafficking & Forced labor

- Commodity Theft and Smuggling

- Illicit mining

- Oil theft, refining, and smuggling

- Protection Economies

- Criminal Gangs

See also TC 7-100.3 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 4: Criminals

- ↑ The DATE countries listed below are fictionalized territories at the national and first-order administrative levels (i.e. province or county depending on the country). Lower order boundaries such as city wards and municipalities, and physical features such as mountains, rivers, and deserts, have retained their actual names. In many cases literature and media sources will use more than one name for a feature, and may spell them in different ways. As practicable, DATE will follow the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency's guidance contained in the Geonet Names Server (GNS), "the official repository of standard spellings of all foreign geographic names sanctioned by the United States Board on Geographic Names (US BGN)". However, the reader should be cautioned that reference texts and maps may use these other variants. These common variants are also listed in the GNS.