Africa

The purpose of the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE)-Africa is to provide the US Army training community with a detailed description of the conditions of four composite operational environments (OEs) in the African region. It presents trainers with a tool to assist in the construction of scenarios for specific training events but does not provide a complete scenario. DATE-Africa offers discussions of OE conditions through the political, military, economic, social, information, infrastructure, physical environment, and time (PMESII-PT) variables. This DATE applies to all US Army units (Active Army, Army National Guard, and Army Reserve) and partner nations that participate in DATE-compliant Army or joint training exercises.

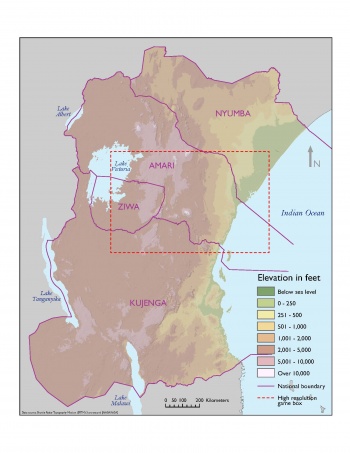

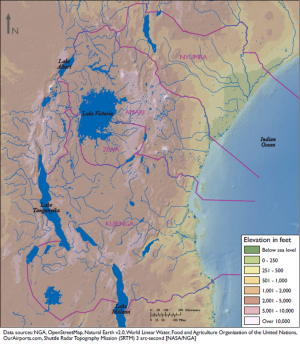

Over 795,000 square miles comprise DATE-Africa, a varied and complex region which ranges from Lake Victoria in the west to the Indian Sea on its eastern coast. The region includes the fictional countries of Amari, Kujenga, Ziwa, and Nyumba. The region has a long history of instability and conflict; ethnic and religious factionalism; and general political, military, and civilian unrest. In addition to these internal regional divisions, outside actors have increasing strategic interests in the region. DATE-Africa thus represents a flashpoint where highly localized conflict can spill over into widespread unrest or general war.

(See also Providing DATE Feedback, Using the DATE and TC 7-101 Exercise Design).

Key Points

- The countries in the region have experienced dramatic changes in governing regimes over the last few decades.

- Political, economic, and environmental changes have created societal pressures that spawn conflict between nations, political factions, international players, and potential threat actors.

- The complex tapestry of ethnic, tribal, linguistic and religious loyalties make diplomatic and military operations in the region difficult.

- US forces may be required to conduct operations in the region in a wide range of roles and will likely operate in a combined effort with other forces.

Discussion of the OEs within the DATE-Africa Operational Environment

Republic of Amari

Amari, with its capital at Kisumu, is a functioning and relatively stable democracy, receiving significant support from the US and other western countries. A new constitution, implemented seven years ago, has attempted to create a framework for better governance with good results. Ethnic and tribal tensions play out in multi-party politics, which has led to a history of electoral violence and distrust of the government. The last election, was uniquely free of the violence of past elections. Other concerns include border security, instability spillover from neighboring countries, regional competition for resources, and terrorism.

Amari gained independence from a western European colonial power fifty years ago; a time when colonial powers were divesting themselves of their African colonies. Since then, Amari continues to be a functioning and relatively stable democracy, receiving significant support from the US and other western countries. The government consists of an executive branch with a strong president, a bicameral legislature, and a judiciary with an associated hierarchy of courts. Amari is making significant progress in areas of good governance, but still struggles with institutional corruption. The new constitution has attempted to create a framework for better governance with good results. Ethnic and tribal tensions still influence multi-party politics, contributing to the history of electoral violence and distrust of the government. Other concerns include border security, instability spillover from neighboring countries, regional competition for resources, and terrorism.

The Amari National Defense Force (ANDF) is the state military of Amari. Its composition, disposition, and doctrine are the result of years of relative peace, but near constant internal security concerns and regional threats. Internal security and the constant struggle against border incursion continue to shape its structure and roles. The ANDF consists of the Amari Army, Air Force, and Navy. Amari paramilitary forces, include the Border Guard Corps (BGC) and Special Reserve Force (SRF). The ANDF is a well-integrated and professional force with good command and control and high readiness. It has a limited force projection capability and a mix of static and mobile forces. Amari is an active contributor to both regional and international peacekeeping forces and has hosted such forces within its borders.

Republic of Ziwa

The Ziwa People’s Defense Force (ZPDF) is the state military of the Republic of Ziwa. Its structure and focus has adapted over the last decade alongside the country’s economic development. The ZPDF consists of the Ziwa Ground Forces Command (ZGFC), Ziwa Air Corps (ZAC), and the National Guard. Ziwa’s military relations with its neighbors – Amari to the north and Kujenga to the south - is generally stable, despite sporadic low-level incidents along the border. The scope of border control operations has contributed to the forward deployment of dedicated maneuver elements and leveraging of former rebels to ensure the appearance of security.

Multiple threats exist to exploit Ziwa’s dependency on natural resources and external power generation and transmission. Brutal militants in the northeast mountain area (“The Watasi Gang”) and pockets of ethnic rebels throughout the country continue to plague stability and keep the military at continually high operational tempo. Although both Kujenga and Amari have active security agreements with Ziwa, rumors persist of covert support to the rebels by both countries.

Republic of Kujenga

Kujenga gained semi-independence fifty-six years ago under a post-colonial United Nations mandated trusteeship. Three years later, Kujenga gained full independence, establishing a constitution built on a single political party system.

Working under the UN mandate, the outgoing colonial power lent support to the group of elites who had made up the bureaucracy under colonial rule. These elites united under the political party People of Change (POC). They have since maintained control of the government through successive elections, except for a brief experiment with multi-party rule seven years ago that ended five years later with the subsequent election. Kujenga established diplomatic relations with the United States when it gained independence fifty-three years ago. Relations between the two countries have been strained at various times because of Kujenga’s tight-knit oligarchic political structure and its repressive tendencies. Ongoing tensions and violence between the Kujengan government and the Tanga region brought US condemnation. The Kujengan government is focused on addressing rampant corruption and government inaction, but the country has also experienced a shrinking of democratic space.

The Kujenga Armed Service (KAS) is the state military of Republic of Kujenga. It emerged from a somewhat turbulent past and a range of internal security challenges. Kujenga’s military relations with its neighbors are relatively stable, although border security issues despite ongoing tensions in the Tanga region increasing the risk of regional conflict. The KAS consists of the Kujengan Army, Kujengan National Air Force (KNAF), Kujengan National Navy (KNAV), and Security Corps. Kujenga’s primary internal security concerns include Tangan separatists, violent bush militias in the central mountains, and the brutal "Army of Justice and Purity" guerrillas in the Kasama region. External threats include border incursions by presumed Amari paramilitaries and cross-border smuggling.

Democratic Republic of Nyumba

The government is authoritarian in all aspects. Beginning fifty-nine years ago, a military coup overthrew the newly elected civilian government, lasting only six years before an Islamist government took power. While the government remains Sharia law-based, tribal influences permeate and dominate the government as well. Economic, religious, ethnic, and tribal interests collide, collude, and complicate the politics of Nyumba and have led to decades of civil war and other internal conflicts. These conflicts have threatened border countries with refugees and provided a safe haven for terrorists, insurgents, criminals, and other disrupters. These deep-seated challenges show no signs of dissipating.

The Nyumban Armed Forces (NAF) is the state military of Nyumba and is key to the country’s stability. It has experienced significant challenges from both the various threat actors in Nyumba, and distrust within its ranks and from politicians. Civilian distrust is particularly high, leading to widespread tribalism and the rise of armed militias. Its composition and deployments are driven by political desires to maintain control of key forces and the de facto ceding of territory to tribes or armed groups. The NAF consists of the Nyumban National Army (NNA), the Nyumban Armed Forces Air Corps, and the Nyumban Navy. The Nyumban National Security Service controls a paramilitary group, the Rapid Security Forces (RSF) which is usually deployed in support of border and anti-insurgency operations. The NAF has inherited a varied structure and culture due to several regime changes and colonial legacy. The lawlessness of the territory and general instability has heightened both political and military leaders’ wariness of the forces.

Strategic Positioning

This OE is one of the most politically dynamic regions in the world. Almost nowhere else have geopolitical forces and regional ambitions combined to produce such volatile results. State developments ranging from gradual reforms to often violent regime change have occurred throughout the region's history. Although the region may not have been the focus of geopolitical contestation, it has been often a factor in the larger geopolitical landscape. This volatility is not likely to change in the coming years as greater multipolarity continues to increase throughout the region.

Coinciding with increased international interest, the region's states have grown stronger over the past several years, exerting their sovereignty in ways that challenge the post Cold War development and humanitarian models. International players have increased pressure to gain a foothold on the continent. As the countries in the OE reach out to forge new relationships, they find a range of willing potential partners with a diverse set of motivations. Non-state threat actors have also found fertile ground for often extremist messages. Uneven economic growth and the injection of international anti-terror military aid have empowered some states while channeling resources to specific interest groups in power, specifically to the executive and security sector. However, this will not guarantee stability or equitable human development over the next five years. Rather, the region may see a situation in which as more and more money pours into the system, alternate seats of power and contestation may arise, threatening not only national but regional stability, development, and integration.

Strengthening centers of power could prevent non-violent political change from emerging. Ambitious leaders in the periphery may then resort to violence to unseat ruling regimes that themselves came to power as products of deeply embedded ethnic conflicts, cross-border regional power projection, and horizontal inequalities that hamstring equitable development. Thos OE is often viewed as a 'political marketplace,' the challenges of which could begin to lead the region down a violent path. The region has always had to weather changes in the international context while also managing significant local political conflicts and economic problems. The legacy of internal legitimacy deficits co-exists within an international context that often undermines the development of local solutions. While regional integration has increased regional stability and the level of cross border interference has declined, the future is anything but certain, as international, regional, and national forces strain the ability of national and regional institutions to regulate and manage non violent change.

Regional Views of the US

The countries of the OE voice mixed views of American soft and military power. There is little consensus about U.S.-style democracy and many who oppose the spread of American ideas and customs in Africa and around the world. At the same time, many in the region still believe the U.S. respects the personal freedoms of its people and aspire to similar freedoms. While the U.S. and other nations have been involved in widely-popular peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, the presence of outside forces has been a rallying cry for disenfranchised groups. The general pull away from U.S. intervention in the region has been aided by aggressive inroads from other external countries, such as Olvana, that promise to supply an alternative to previously undisputed economic and military power.

Regional PMESII-PT Overview

Political

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque nec metus ante. Vestibulum hendrerit viverra vehicula. Donec a mi velit. Praesent at lacus ut leo dapibus cursus. Vestibulum a aliquam metus. Vestibulum volutpat neque ac felis tempus, sit amet lobortis mauris condimentum. Aliquam suscipit metus diam, sed ultrices purus elementum vel. Morbi quam arcu, rutrum ut ligula vel, blandit pretium leo. Integer et nunc vel lectus interdum rhoncus nec eu lectus. Etiam tristique, lorem quis lacinia tempus, diam eros aliquet ipsum, gravida venenatis ipsum magna sed turpis. Ut elementum nisi quis nisi lobortis, at facilisis risus aliquam. Sed aliquet felis sapien, sed pellentesque lectus fringilla quis. Praesent ex turpis, tristique eget imperdiet sed, interdum quis felis.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics |

|

|

|

|

Military

The countries represented in DATE:Africa are a cross-section and composite of states and state forces. State forces have evolved from a diverse set of conditions including colonial histories to a succession of regime changes and revolutions. They are generally pragmatic in both structure and equipment - the result of constrained budgets and constantly changing threat conditions. The forces of the more modernized countries, such as Amari and Ziwa, are generally more integrated, better equipped, and more professional. At-risk countries, such as Kujenga and Nyumba demonstrate tribal or ethnic segregation, degraded readiness, and a structuring for regime survival. Participation in regional or international peacekeeping forces and exercises is often as much to train and equip their own forces as to develop interoperability and cooperation. A variety of threat groups and endemic criminal activity throughout the region contend to destabilize governments or build power in difficult-to-govern areas.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military |

|

|

|

|

Economic

The economic conditions in the four countries cover a wide spectrum. Ranging from modern economic systems to reliance on traditional cash-only systems. In all of the countries the underlying structure of family and tribe motivate most economic transactions and policies.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic |

|

|

|

|

Social

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Pellentesque nec metus ante. Vestibulum hendrerit viverra vehicula. Donec a mi velit. Praesent at lacus ut leo dapibus cursus. Vestibulum a aliquam metus. Vestibulum volutpat neque ac felis tempus, sit amet lobortis mauris condimentum. Aliquam suscipit metus diam, sed ultrices purus elementum vel. Morbi quam arcu, rutrum ut ligula vel, blandit pretium leo. Integer et nunc vel lectus interdum rhoncus nec eu lectus. Etiam tristique, lorem quis lacinia tempus, diam eros aliquet ipsum, gravida venenatis ipsum magna sed turpis. Ut elementum nisi quis nisi lobortis, at facilisis risus aliquam. Sed aliquet felis sapien, sed pellentesque lectus fringilla quis. Praesent ex turpis, tristique eget imperdiet sed, interdum quis felis.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social |

|

|

|

|

Information

The OE countries all recognize the importance and influence of information media and it's control. Approaches range from low technical capabilities with tight government controls to rapidly modernizing technical capabilities with ineffective attempts by the government to control the public's perceptions. New means of information sharing using modern technology are rapidly adopted by the population unless the government intervenes in an attempt to control information flow. Countries jump directly from limited land-line telephone systems to ubiquitous cell phone use. Distances and improvements in technology, software, and infrastructure allow African countries to implement new information systems at a very rapid pace. In several instances, African countries are on the cutting edge of adopting new information technology to enhance the public's standard of living. Other instances see the leadership of a country attempting to control access to information systems to remain in power and to exploit it for their own benefit.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information |

|

|

|

|

Infrastructure

African infrastructure is expensive. Long distances, low population densities, uneven management, and intraregional competition contribute to these costs. African infrastructure projects emphasize expensive rehabilitation over basic maintenance. The World Bank estimates that about 30 percent of Africa’s infrastructure requires rehabilitation – even more in rural and conflict-prone areas.

Despite the cost, both domestic and international players are keen to expand Africa’s infrastructure. States control most infrastructure systems, but public-private partnerships (PPP) are increasingly more common. The World Bank and international development finance institutions provide most of the financing, followed by domestic government financing. Olvana is the largest financier and constructor of African infrastructure.

The typical project involves a consortium of non-African state development agencies, international government organizations, private financiers, and construction companies. Following the financing announcement, spending or progress is hard to trace until the project is complete. A large portion of the announced projects are either scaled back or never completed. In some cases, competing projects do not have the demand to justify the large investments.

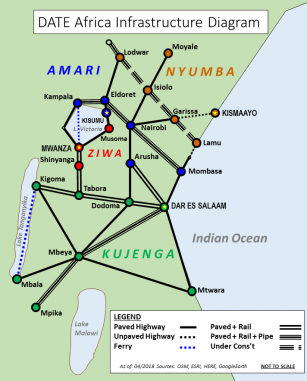

Developed infrastructure correlates with population density. Amari’s main cities: Nairobi, Kampala and Mombasa, are key nodes of the 800-mile Northern Victoria Corridor, a road, rail, and pipeline network. Kujenga follows Amari in both population and infrastructure development, with the competing Dar Es Salaam - Kigoma, DARGOMA, Corridor linking the Indian Ocean port of Dar Es Salaam with Lake Tanganyika and Ziwa’s capital, Mwanza, on the southern shore of Lake Victoria. A major north-south transportation artery runs through Moyale in Nyumba, crossing into Amari just south of Isiolo, through Nairobi to Mbeya, Kujenga in the south. Nyumba, Amari, and Kujenga all compete to be the Indian Ocean gateway of choice to landlocked countries.

Lastly, proposed infrastructure projects are increasingly gathering strong opposition through both standard and social media, quickly gathering international support. The more disruptive to the environment, the more opposition they garner. Examples include port expansion and coal power plant construction in Lamu, Nyumba, and transportation corridors bisecting wildlife ranges in all four countries. While opposition campaigns often start on social media sites and increasingly evolve to on-site demonstrations.

| Amari | Kujenga | Nyumba | Ziwa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Summary/Condition | Have-use-fix | Have-use-don’t fix | Either had-degraded or never-had | Have-use-don’t fix |

| Highway Density (km/100km2) | 5.7 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 4.4 |

| Airports w/ Paved Runway >8,000 ft | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Deep Water Ports/Berths | 1/19 | 4/19 | 1/4 | - |

| Electricity Production/Consumption (MW) | 2300 | 1700 | 130 | 60 |

See also: Amari Infrastructure, Ziwa Infrastructure, Kujenga Infrastructure, Nyumba Infrastructure

Physical Environment

Though making up less than a fifth of Africa, the DATE Africa region includes most of the geographic and climatological features present on the continent. The central features are the East and West African Rift Valleys that run from Kujenga in the south all the way to northwest Nyumba in the north. They are home to the African Great Lakes which are the origins for both the Congo and Nile Rivers. Their peaks also make up the highest elevations in Africa. Eastward from the Rift, descending savannah and desert meet the Indian Ocean along an expansive coastline containing the natural deepwater ports of Dar Es Salaam in Kujenga, Mombasa, Kenya, and to lesser extents Lamu and Kismaayo in Nyumba.

| Amari | Ziwa | Kujenga | Nyumba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Environment |

|

|

|

|

| Land Area (km2)

o |

||||

| tal Area (land+inland water - km2) |

Time

All DATE Africa countries use the Gregorian calendar. However, within that daily routine great importance is paid to the rising and setting of the sun. As is common in equatorial Africa, none of the regional countries observe Daylight Savings Time (DST).

Whilst Western approaches to time are o’clock, or by the clock; regional attitudes towards time are the opposite. In many rural areas some of the elder population might not even have access to a clock or watch. However, their apparent lack of concern for clock time should not be mistaken for an inability to accomplish key tasks. The local populations will commit energy to their tasks with great industry, on their timetable, to achieve their own goals.

Across the whole region there is a much more flexible approach to time. ‘Africa time’ is very much a thing. In short, Africa time means things will happen when they happen; there is no point worrying about what might be. For example; you cannot control the rain, if it rains and crops grow, so be it. Conversely, if it doesn’t rain they will not grow. You cannot plan to harvest crops which depend on rain because you cannot control the rain.

Once the differing approach to time is understood, business with the Amari should be straightforward. Attempting to rush them, or impose a Western approach to time will not be of benefit to either US forces or the host nation. This is the case in the cities as well as the countryside.

Time Zone Observed - UTC +3 (East Africa Time - EAT) DST NOT observed.

Significant Conditions in the OE

Peacekeeping Forces

- International Peacekeeping Forces.

Description goes here Recent examples of peacekeeping forces with and international mandate include the forces of the UN mission in DATE Africa and the European Training Mission in DATE Africa.

- Regional Peacekeeping Forces.

Description goes here Recent examples of regional peacekeeping forces include the forces of the Regional Standby Force and the Regional Monitoring Group's Regional Economic Community Security Force.

Private Security Forces

- Corporate Private Security Forces.

Wealthy individuals and businesses may contract the services of corporate security forces. These forces are highly disciplined, organized and trained - recruiting mostly from former elite military and paramilitary forces. They are often used for high-end site and VIP security. They are capable of conducting small-unit, high-risk strikes with state-of-the-art equipment and vehicles. They have a significant intelligence and planning capability. While highly effective and fiercely loyal to their employer, they may have the propensity of over-aggression and risk extra-judicial actions. They may contract local security companies (see below) for mundane activities. Examples: Jaguar Integral Defence Services International (JIDSI).

- Private Security Companies.

Rampant crime and inadequate policing, particularly in the urban areas has led to the rise of numerous private security companies. These companies provide security services for businesses and individuals ranging from static guards to armed response teams. Guarded facilities will likely have barbed wire and monitored cameras. The guards themselves are variously uniformed, from simple reflective vests and caps to military-style garb. They will either be unarmed (batons, irritants) or have a variety of small arms. The quality and cost of the services may indicate the professionalism of responses and adherence to company rules of engagement. These guards are often well-regarded in the community and may have excellent situational awareness of local activities and dynamics, as well as those of the poorer areas from which they are often recruited. Note: Non-commercial "neighborhood watches" may exist, but are less likely to be armed or provocative.

See also: TC 7-100 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 5, Noncombatants - Private Security Contractors

Non-Governmental Organizations

A wide range of Nongovernmental Organizations (NGO) operate within the OE. Many are focused on education, medical, and economic development. Some organizations center their activities on humanitarian assistance for displaced persons and supporting camp operations. These groups have typically been vulnerable to attack and corruption by various threat actors in the region. UN and Coalition elements, as well as privately-contracted security have been used by these groups to ensure uninterrupted movement and operation.

See also: TC 7-100 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 5, Noncombatants - Nongovernmental Organizations

Hybrid Irregular Armed Groups

The variety of armed groups operating within the OE is indicative of its complex and dynamic political, economic, ethnic, and religious issues. Their structures are as diverse as their ideological drivers. Most are not pure insurgencies, guerrilla groups, or militias, but rather hybrids of all of these. The key differentiators of these groups is their relative mix of forces and the primary driver of their actions.

Violent Extremist Organizations. There are a number of international or transnational Higher Affiliated Violent Extremist Organizations (VEO) presently operating within the OE. Many of these groups have indigenous origins, but have since affiliated with external groups for support and identity. Others may have their origins outside of the OE and gained a foothold on the continent. These hybrid organizations have the capability to organize and execute high-impact attacks against public targets and may be able to mass to conduct semi-conventional operations across the OE.

Major known groups in the OE include Islamic Front in the Heart Africa (AFITHA) and Hizbul al-Harakat. The volatility of security situations across the OE allow rapid growth and morphing of extremist groups as they position for power and influence. Groups will change their tactics and affiliations to adapt to evolving country and regional dynamics.

Insurgencies. Whether motivated by political, religious, or other ideologies, these groups will promote an agenda of subversion and violence that seeks to overthrow or force change of a governing authority. The composition of these in the OE is almost always a hybrid of insurgent elements and guerrilla forces, depending on the locale, goals, and levels of support. They may act as the militant arm of a legitimate political organization. These groups will undermine and fight against the government and any forces invited by or supporting it. They are likely to target government security forces and even civilians to demonstrate force and create instability. They will conduct small operations, such as kidnapping, assassination, bombings, car bombs, and larger military-style operations. Examples: Amarian People’s Union, Free Tanga Youth Movement.

Separatist Groups. These groups consist mostly of former (losing) soldiers that fought in a previous revolution or coup. Rather than fighting to overthrow the current regime, their focus is to secure a territory and gain officially recognition. These groups will likely have widespread support in the controlled area and view government or external forces as the enemy. They may provide security for commercial or NGO movement for a fee or to curry favor. Separatists will be very protective of their designated borders and may react disproportionately to perceived incursions. Example: Pemba Island Native Army.

Ethnic or Religious Rebel Groups. Numerous conflicts that are highlight ethnic, linguistic, or religious differences have led to the development of ethnicity-focused armed groups. Some groups have developed in self-defense against such groups, then gone onto be violent themselves. Extreme passions of these groups have led to often brazen atrocities, causing massive waves of IDPs. Multiple UN interventions may have temporarily quelled the violence, but long-held grievances give life to renewed violence. These groups may conduct raids, extrajudicial killings, targeted killings of civilians, and summary executions. There have been reports of rebels luring villagers to their town center for execution, often throwing bodies into the village water source to spoil it. These groups may attempt to seize strategic routes to assert control and raise funds. Examples: Army of Justice and Purity (AJP) and Union of Peace for the Ziwa.

Local Armed Militias. These groups usually have a local focus and may be independent or supported by a local strongman. Their forces are mostly comprised of former soldiers or paramilitary who may have fought for the state, but now serve their own interests. They generally carry small arms, but may have additional capabilities, depending on the goals and support. Moderate factions of these groups may conduct demonstrations, vandalism to force political concessions, while more radical factions conduct small attacks, riots, sabotage to enforce a particular ideology. In rural areas, they may be heavily armed and appear almost like a guerrilla force. In urban centers, they may resemble a gang or an insurgent group. Examples: Mara-Suswa Rebel Army (MSRA), Kujengan Bush Militias.

See also TC 7-100.3 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 2: Insurgents and Chapter 3: Guerrillas

Criminal Organizations and Activities

The often unstable economic and security situations across the continent have allowed criminal activity and corruption to flourish. Elsewhere in the world, corrupting and co-opting of government officials by criminal enterprises is usually to gain operating freedom. In the OE, such activities are competitive enablers, intended to gain access to internal and external markets. How these large-scale domestic criminal enterprises and international criminal manifest within the OE are characteristic of each country's circumstances and history.

Criminal enterprises may have a pronounced impact on military operations in the REGION OE. Dominant criminal elements may view external military forces as a threat to their territorial control, while less-powerful organizations may look to exploit shifts in security and rules of engagement to gain access to markets or power.

The main categories of organized criminal enterprises within the OE include:

- Drug Trafficking

- Human Trafficking & Forced labor

- Commodity Theft and Smuggling

- Illicit mining

- Oil theft, refining, and smuggling

- Protection Economies

- Criminal Gangs

See also TC 7-100.3 Irregular Opposing Forces, Chapter 4: Criminals

| DATE Africa Quick Links . | |

|---|---|

| Amari | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Kujenga | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Nyumba | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Ziwa | Political • Military • Economic • Social • Information • Infrastructure • Physical Environment • Time |

| Other | Non-State Threat Actors and Conditions • Criminal Activity • DATE Map References • Using The DATE |